SPECIAL REPORTS

Data: 3 January 2020 Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

The Collapse of the INF Treaty and the US-China Rivalry

Russia’s noncompliance with the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF Treaty, was the top reason for Donald Trump’s administration to pull out of the deal. Nonetheless, the collapse of the agreement has influenced not only the situation in Europe but also in Asia and the Pacific.

- A non-signatory of the INF deal, China has long been committed to developing its medium-range missiles that pose a threat to the U.S. naval fleet and military facilities in the Pacific, as well as Washington’s allies in East Asia.

- U.S. and Russian decisions to terminate these countries’ participation in the agreement is bad news for China as the Asian country now holds the world’s fourth-biggest nuclear inventory. With the INF Treaty in force, China had a kind of security guarantees that allowed it to upgrade its arsenal. Russia, and especially the United States, can respond to Beijing’s newly updated nuclear stockpile by fielding its medium-range missiles close to Chinese territory.

- It has been estimated that 90 percent of China’s ground missile arsenal would be outlawed. The Chinese have taken advantage of an increased number of medium-range missiles in the inventory to enhance their anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities. By using these weapons and strategies, China can keep the U.S. Navy away from the contested areas in the seas off the Chinese coast. Medium-range weapons are a compelling argument that China has in relation to its neighbors, chiefly those with whom it is at loggerheads.

- The U.S. administration believed that the INF Treaty impaired efforts to neutralize Chinese influence in Asia. Without the deal, the United States could easily exert pressure on Beijing, also by fielding its medium-range nuclear missiles on Asian soil. This in consequence may change both the balance of power in Beijing’s relations with Taiwan and the situation in the South China Sea region.

Chinese strategy

China has for years seen the INF Treaty as a guarantee of its security. The U.S.-Russia deal long protected Beijing against the deployment of medium-range weapons by Russia, its mighty neighbor, and the United States, with the latter’s excellent maritime and military capabilities. Meanwhile, China has beefed up its medium-range ballistic inventory, especially in recent years.

The United States is the world’s biggest naval power, but the Middle Kingdom has emerged as its top rival close to the Pacific waters adjacent to Chinese provinces. The reason is simple: neither is the United States able to deploy its forces to this region rapidly, nor can it keep them on high alert, a move that could oblige the U.S. Armed Forces to shift their troops from elsewhere. Beijing is bolstering its military potential while ramping up its influence on the adjacent waters. China, which has never been a party to the INF Treaty, could update its vast arsenal of conventional weapons, the core of China’s anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) weapon system. This includes so-called carrier killer missiles like the DF-21D, which can target aircraft carriers at a range of 1,500 kilometers. If the US-China war broke out sometime soon, the U.S. Navy, or the very essence of America’s military might in the Far East, would find itself in an awkward position. Deprived of the possibility of striking targets at Chinese anti-ship missile systems, hidden inland from the sea, U.S. aircraft carriers deployed off the Chinese coast would become an easy target. Chinese-built medium-range ballistic weapons are capable of defeating targets located on the territory of U.S. allies, including those of Japan and South Korea. Also, this represents a grave threat to Taiwan. Last but not least, the United States could find it challenging to retaliate as nearly the whole of East and Southeast Asia is within the range of Chinese missiles –– like Japan that saw heightened tensions amidst the Senkaku Islands, the island chain in the East China Sea claimed by both Tokyo and Beijing. China has in the past showcased its readiness to deploy missile capabilities to intimidate adversaries in what was identified as a brief war. Such was the case of what occurred during the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis when Beijing fired a set of DF-15 missiles, prohibited under the INF deal, off Taiwan’s coast.

What remains a flashpoint in the region is the South China Sea, with China considering roughly the whole of the body of water its territory and brushing aside the claims of other nations surrounding the contested area. Beijing’s territorial claims in the South China Sea have come to voice after China started building artificial islands that became somewhat like its military strongholds. The United States labeled Chinese efforts as an attempt to militarize the sea while voicing its concern over the use of military facilities to restrain the freedom of navigation in a critical region for worldwide trade. But China does not seek compromise in this matter. It refused to recognize the international court ruling over its island and maritime disputes with other countries, including the Philippines and Vietnam. China has fielded some of its intermediate-range ballistic missiles in the contested South China Sea, where it conducted a series of missile tests. Like in the summer of 2019 when Beijing test-fired more than just one anti-ship ballistic missile in the area around the human-built Spratly Islands. Pentagon spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Dave Eastburn later said the missile launch was disturbing and contrary to Chinese pledges that it would not militarize the waterway.

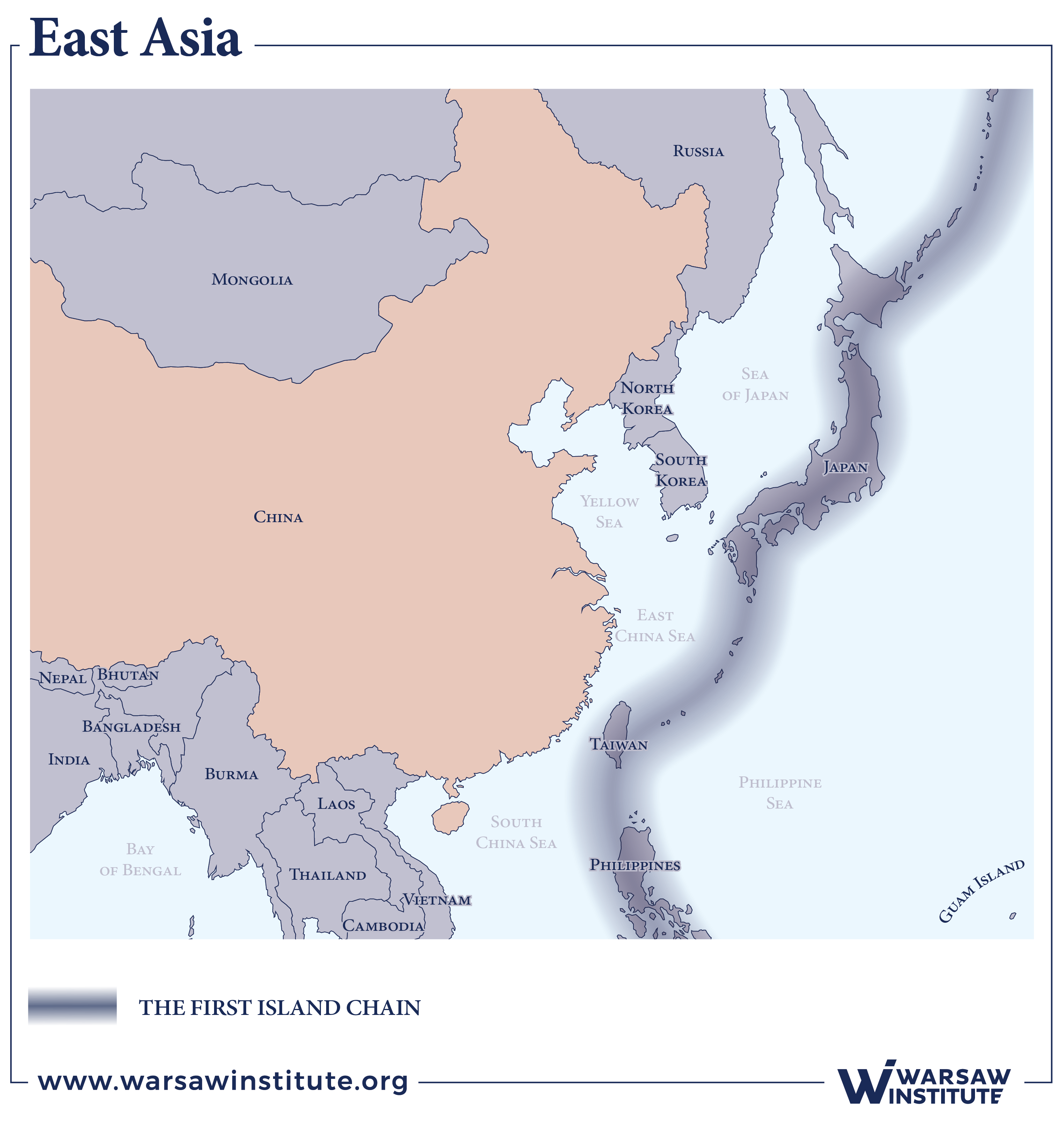

Chinese ground medium-range missile launchers are now a strong link in the national defense system as they aim to protect the country against seaborne attacks. Chinese-made weapons could neutralize unfriendly warships, especially aircraft carriers, at a safe distance off the Chinese coast to prevent an enemy from firing targets in eastern and southern regions of the country. China has in its stockpile many medium-range missiles, most prominent of which are the DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles. To nullify Chinese launchers, the United States would need to field its medium-range weapons also on Japanese territory. In his testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee in July 2018, U.S. Army General Mark A. Milley, nominee to become the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that warhead-tipped conventional ground medium-range missiles might help deter the increasing military threat from China. Beijing seeks to mirror its successful economic transformation, this time in the military, to make its army more modern and one of the world’s mightiest, yet not only in size. A gigantic fleet upgrade program is currently underway, with the mission to make China both a continental and maritime power. China’s naval might is bolstered by its anti-ship missile systems deployed along the coast to prevent U.S. aircraft carriers from operating in the waters between the continental mainland coast and the first island chain . This is where the Chinese have a new generation of the DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles (1,500 kilometers range) and the DF-26D (4000 kilometers range).

Chinese inventory

Of all Asian countries, only ten have INF-type missiles, though these are mainly short-to-medium-range systems that fly 500–1,000 kilometers. Only a few states may have medium-range (1,000–3,000 kilometers range) or intermediate-range (3,000–5,000 kilometers range) ballistic missiles. Taiwan is reported to have 200–300 rockets with a range of 500–1,000 kilometers, and may be building another one hundred enhanced versions that can reach targets located 3,000 kilometers away. North Korea has hundreds of missiles with a range of 500–1,000 kilometers and 1,000–3,000 kilometers. India and Pakistan each have about fifty weapons with ranges between 500 and 3,000 kilometers. India also has a handful of intermediate-range missiles, with a range of up to 5,000 kilometers. But it is China that holds the position of the top missile power across the continent. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has a vast nuclear inventory, including missiles designed to destroy aircraft carriers and military bases, both of which are the core of U.S. military dominance across the region and its ability to protect allied forces. In its 2018 report, the Pentagon wrote that the People’s Republic of China had an inventory of more than 2,000 ballistic and cruise missiles of various ranges. China has the largest and most diverse ground-based missile force in the world. Most Chinese missiles can be tipped with either conventional or nuclear warheads.

Recent years have seen new short-, medium- and intermediate-range missiles added up to the Chinese nuclear inventory. The DF-15B has been updated with a guided warhead and an extended range of more than 600 kilometers. Newer missiles in the DF series –– the DF-12 SRBM, the DF-16 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) and DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) — have increased weight and range, with more accurate warheads. The DF-16, first revealed publicly in September 2015, has a range of over 1000 kilometers and a warhead of over 500 kilograms. In Chinese arsenal there is also the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile, or a modified JL-1 submarine-launched ballistic missile. The road-mobile DF-21 has a range of over 2,000 kilometers. Another Chinese missile system is the Chang Jian (Long Sword,), or CJ-10, which is a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) Hundreds of Chinese-built weapons have a range between 500 and 1,000 kilometers and can strike targets in Taiwan. Roughly a hundred of missiles in the Chinese inventory have a range of up to 3,000 kilometers and are mainly designed for U.S. aircraft carriers. China deployed its first brigade of intermediate-range missiles (3,000–5,500 kilometers range) in 2016. If it has two to three brigades, it would have forty to sixty such missiles. Added to that should be a few hundred INF-class cruise missiles. Then China would have about 150 conventional ballistic missiles that can reach Japan’s main islands and about fifty that can reach Guam.

In Beijing’s nuclear stockpile there are its most dangerous missiles in the context of military rivalry with the United States, or the new-generation Dongfeng DF-21D and DF-26D medium-range anti-ship ballistic missiles. Beijing first displayed the former weapons at the 2015 China Victory Day military parade marking the 70th anniversary of the victory over Japan in World War II. Once they entered combat service, the DF-21D were labeled as the world’s first ground-launched supersonic satellite-guided jet missiles able to sink an aircraft carrier even if fired at distant targets. The range of “carrier killers,” as nicknamed by the Chinese press, may be between 1,600 and 2,700 kilometers. If fielded along the Chinese coast, the DF-21D missiles could pose a lethal threat to Japanese and Taiwanese naval vessels, as well as for the U.S. Navy and its Seventh Fleet if a conflict broke out in the Taiwan Strait.

In early January 2019, the Chinese military test-fired its DF-26D intermediate ballistic missile, dubbed the “Guam killer” weapon and unveiled at a military parade in 2015. Beijing has recently deployed these road-mobile missiles, carried on trucks that often change location, in northwestern China’s plateau and desert areas. What, in addition to ASBM, may represent yet another major threat to the U.S. Armed Forces are Chinese-built cruise missiles, including the CJ-10 land-attack missiles with a reported range of over 1,500 kilometers, as well as its variants, among which are supersonic missiles able to perform fast maneuvers and fly at least five times faster than the speed of sound. The United States has limited capabilities to counter this kind of missiles. There are no ground-launched medium-range missiles, and to get Chinese-based targets within the range of U.S. Tomahawks, naval vessels would need to approach close enough to sail into the range of the DF-26D missiles. Also, the newest-generation JASSM and JASSM-ER air-launched cruise missiles are able to fly not as far as China’s DF-26D can.

Bejing’s stance on the INF Treaty

Beijing bemoaned Washington’s decision to leave the pact, blaming the United States for “ignoring its international commitments.” Moreover, China warned that the U.S. deployment of medium-range missiles in Asia would lead to destabilization of the region. The Beijing government saw Trump’s leaving the INF Treaty as part of the anti-China campaign, though the United States formally quit the deal amidst Russia’s noncompliance.

Source: KREMLIN.RU

When the U.S. leader first threatened to exit the pact, this provoked alarm among Beijing officials who became fearful of losing their country’s security guarantees granted by the U.S.-Russia agreement. “The U.S. unilateral withdrawal from the landmark INF treaty is a mistake that will have a negative multilateral effect,” Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying said on October 22, 2018. What served as the second element of Beijing’s diplomatic efforts to keep the INF Treaty in force was Chinese insistence that the Asian country should not meddle in the Moscow-Washington talks. The U.S. administration argued back then it could renew discussions to sign the extension of the Cold War-era nuclear pact if it went beyond its bilateral format. President Donald Trump told reporters he wanted a new treaty to be inked by both Russia and China. Of course, China could by no means greenlight a step that might strip it off its nuclear stockpile. The Chinese Foreign Ministry said it opposed any efforts to conclude a new agreement yet amended to include the host of new players. “It is now necessary to maintain in force and implement the existing treaty instead of concluding a new one,” China’s Foreign Ministry said in a statement back in early 2019.

The United States and Russia quit the deal, and there has surfaced the issue of the U.S. deployment of its missiles weapons across Asia and the Pacific. China has warned the United States that it would take measures if Washington went ahead with plans to deploy intermediate-range missiles in Asia, Fu Cong, director general of the arms control department at China’s foreign ministry, said on August 6, 2019. The Chinese diplomat called on his neighbors not to allow the U.S. deployment of missiles on their territory in a move that came shortly after U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, on his way to Australia, noted that he was in favor of placing ground-launched, intermediate-range missiles in Asia. On the eve of the U.S. pullout of the landmark 1987 INF pact, Fu Cong said Beijing “will not stand idly by” and watch Washington fielding missiles in Asia. “If the U.S. deploys missiles in this part of the world, at the doorstep of China, China will be forced to take countermeasures,” Fu was quoted as saying. “I urge our neighbors to exercise prudence and not to allow the U.S. deployment of intermediate-range missiles on their territory,” Fu mentioned specifically Japan, South Korea, and Australia. He also echoed insistences that the Beijing government had no interest in taking part in any trilateral talks with the United States and Russia to come to a new version of the INF deal.

U.S. strategy

U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper told a meeting on October 24, 2019, that China posed the biggest threat to the West, with Russia coming second. During a talk at the German Marshall Fund in Brussels, Esper named China’s ambitions as the West’s greatest long-term concern. The Pentagon has enhanced the U.S. Navy’s presence in the disputed South China Sea to challenge China’s assertive military presence in the region.

Washington has voiced concern over China’s nuclear reinforcement plan while struggles to sign a disarmament treaty with Beijing morphed into one of the reasons for the U.S. pullout of the INF pact. China, labeled in the U.S. National Defense Strategy as one of Washington’s “most dangerous rivals, alongside Russia,” was not a party to the treaty. The United States has in the past cared little about China’s poor-quality missiles, but Beijing remains committed to developing its nuclear inventory, surpassing Russia in medium-range missile weaponry.

Back in April 2017, the former commander of U.S. Pacific Command Harry Harris recommended that the United States renegotiate the INF Treaty due to its limited capabilities to counter “Chinese and other countries’ cruise and land-based missiles.” In a testimony submitted to the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee in 2018, Harris observed that the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) controls “the largest and most diverse missile force in the world, with an inventory of more than 2,000 ballistic and cruise missiles.” Harris, who serves now as the U.S. ambassador to South Korea, said that roughly 90 percent of Chinese missiles would violate the INF Treaty if Beijing were a signatory. Testifying at the Senate Armed Services Committee Worldwide Threat Assessment hearing in March 2018, Defense Intelligence Agency Director General Robert Ashley said China continues to “develop capabilities to dissuade, deter, or defeat potential third-party intervention during a large-scale theater campaign, such as a Taiwan contingency.” The head of the U.S. military intelligence services delineated what could be referred to as a somewhat alarming assessment of China’s nuclear weapons program. “Over the next decade, China is likely to at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile,” he added. This may prompt a shift in nuclear policy and strategy –– from a defensive stance that has been in force since 1964, or China’s first nuclear launch, to an offensive one.

James Stavridis, a retired U.S. Navy admiral and NATO supreme allied commander, said China has in fact approached the United States’ military might in the West Pacific region. Back in April 2018, the commander of United States Indo-Pacific Command Philip Davidson said he was in favor of Washington’s pullout of the INF treaty amidst a threat from large Chinese missile forces. “In the Indo-Pacific, the absence of the INF Treaty would provide additional options to counter China’s existing missile capabilities, complicate adversary decision making, and impose costs by forcing adversaries to spend money on expensive missile defense systems,” he said before the Senate Armed Service Committee. What U.S. senior military officials said might have exerted some impact on politicians’ decision to quit the deal. In an interview with a Russian newspaper Kommersant during a visit to Moscow in October 2018, John Bolton, who served back then as Donald Trump’s national security adviser, said China had refused to join the INF deal. He noted that somewhere between one-third and one-half of China’s total ballistic missile capability would violate the treaty, which would suggest the need to sign a new nuclear deal. “The chance they are going to destroy, perhaps as much as a half of their ballistic missiles is just not realistic,” he added shortly after.

Asia and Pacific after the INF

After Washington withdrew from the pact, it might respond to a threat from China by fielding similar weapons alongside the first island chain as these will be capable of reaching Chinese targets both on the continent as well as in the South China Sea and the East China Sea. The situation would change if medium-range missiles were installed. Once fielded in Japan, the island of Guam, southern regions of the Philippines, or even northern Australia, the land-based version of the Tomahawks could halt China’s military aggression across what may deem most feasible war theatres, with no risk to the powerful groups of aircraft carriers. There yet emerges the question of whether the remaining U.S. allies, apart from Guam, would allow having such weapons deployed on their soil. Despite mounting fears over China’s growing military power, Australia, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines are unlikely to welcome U.S.-made medium-range missiles. This somewhat mirrors what happened in Europe, where some of U.S. NATO allies have balked at American weapons amidst fears over Moscow’s threats to become the target of Russian missiles. Like Beijing has warned its neighbors. U.S. allies in Asia need to reckon China’s retaliatory measures in the event of U.S.-made weapons being fielded. Seoul has already bitter experience with hosting the U.S. THAAD missile defense system, to which China responded with economic restrictions.

Amidst the displeasure felt by Washington’s allies in the region, an alternative solution would be to field water- and air-launched missiles as the United States has here a clear advantage over China. Perhaps this would be sufficient to dispatch a bigger number of submarines and aircraft. Guam alone does not solve the problem; the island is small and is located roughly 3,000 kilometers from the Chinese mainland. If dispatched, U.S. missile launchers would be an easy target for Chinese weapons in the event of war breaking out. In order to strike targets on the Beijing-controlled islands or those seen as contested ones, it is sufficient to fire short-range weapons from U.S. military bases in Japan and the Philippines, with mainland China be beyond their reach, though. The U.S. pullout of the INF Treaty, followed by its deployment of medium-range missiles in the Asia-Pacific region, will boost the number of targets China could potentially destroy, which means the reduced firepower Beijing might use when striking any specific target. By dispatching its mobile, hidden, or dispersed missile launchers on Japan’s Ryukyu Islands or in a Philippines jungle, the United States could thwart Chinese military plans.

One should not forget about Russia, either. The demise of the INF Treaty paves Moscow’s way for dispatching its medium-range missiles near the Chinese border. China’s nuclear stockpile has long been what Russian strategists must take into account in their calculations. The emergence of upgraded and high-accuracy Chinese-built intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM) was one of the reasons why Russia began, back in 2007, to threaten to pull out of the landmark nuclear arms control deal.

Beijing has no full-scale nuclear triad, or a military force structure that consists of land-, water-, and air-launched missile. In the event of war breaking out, the United States could easily lock the Chinese military, along with their submarines, inside the first island chain. Therefore, the People’s Republic of China will try its best to avoid an arms race. Earlier Beijing had refused to take part in any arms control talks, especially those pertaining to the INF Treaty. Now it may have no other choice but to seek to join the negotiations, but, given a U.S.-Russian conflict of interests, such an option seems unlikely.

Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

Grzegorz Kuczyński graduated in history at the University of Bialystok and specialized Eastern studies at the University of Warsaw. He is an expert on eastern affairs. He worked as a journalist and analyst for many years. He is the author of many books and publications on the inside scoop of Russian politics.

The publication of the Special Report was co-financed from the funds of the Civic Initiatives Fund Program 2018.

The concept of analytical material was created thanks to co-financing from the Civil Society Organisations Development Programme 2019.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

Wszystkie teksty (bez zdjęć) publikowane przez Fundacje Warsaw Institute mogą być rozpowszechniane pod warunkiem podania ich źródła.