THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 25 July 2017 Author: Jacek Borecki

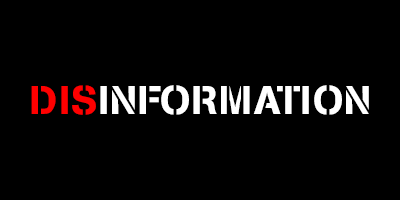

Disinformation as a Threat to Private and State-Owned Businesses

From the spread of the internet to the takeover of the world by smartphones, the technological revolution has redefined the notion of disinformation and propaganda, a tool widely used by Russia and other threat actors. How can coordinated disinformation operations affect society, business, and government?

After the Information Age (1990s) and the “age of the citizen” (2000s), a new era has begun. It is called many things by experts: the post-truth era, or a world where personal beliefs and emotions are more important than facts; the age of the customer, where customers, through popular opinion and review culture have an edge over entrepreneurs, the state, and reputable experts;[1] and, finally, the death of expertise, and the elevation of one’s own, often weak, Wikipedia-supplemented knowledge, over professional research. In addition, methods of communication have completely transformed: a glut of messages can reach a mass audience instantaneously and through many channels. The speed of their transmission and the lack of critical thinking upon those who receive them legitimizes unverified information when users share it on social networking sites. This is the mechanism of modern disinformation.

What purpose does disinformation serve?

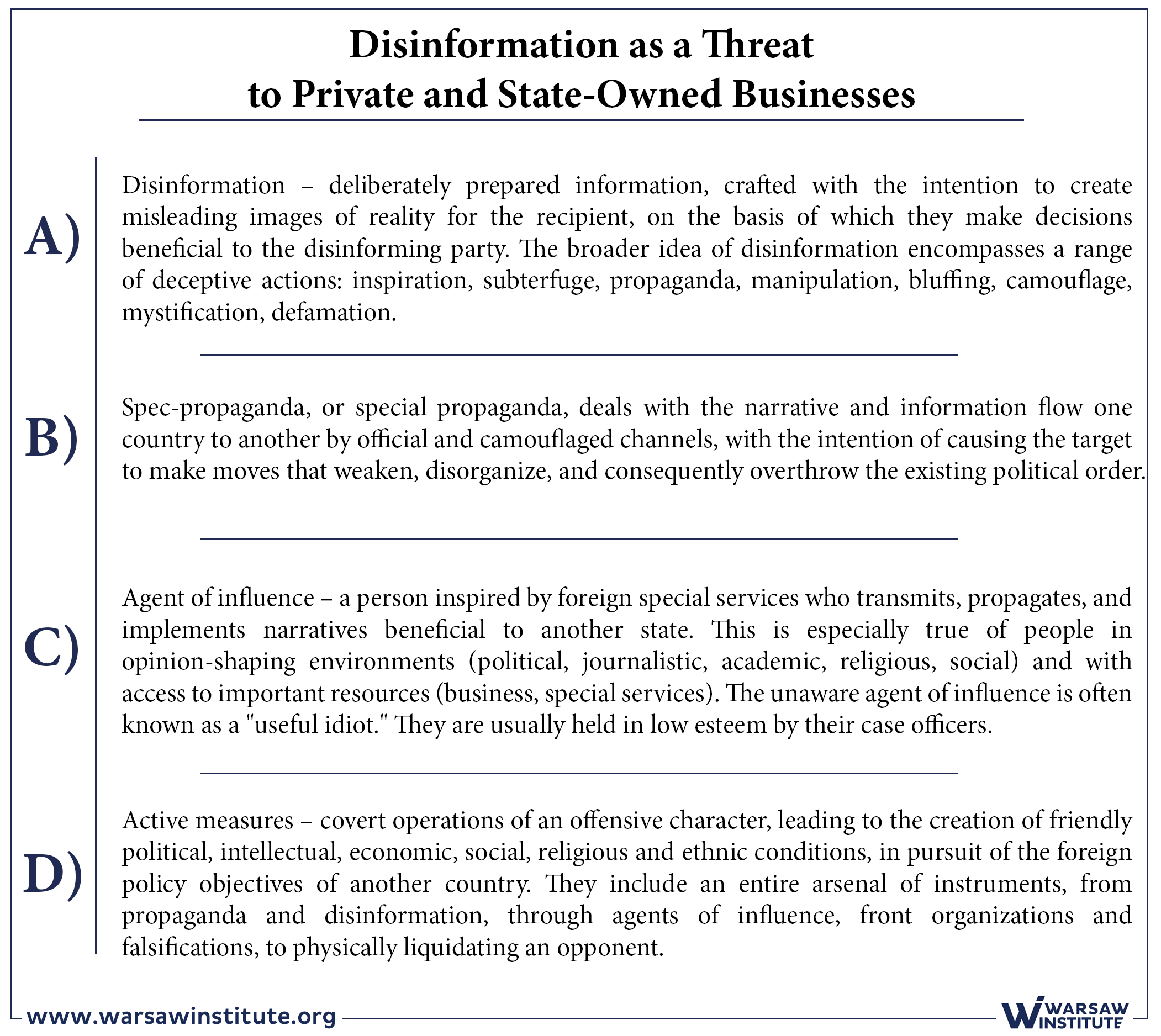

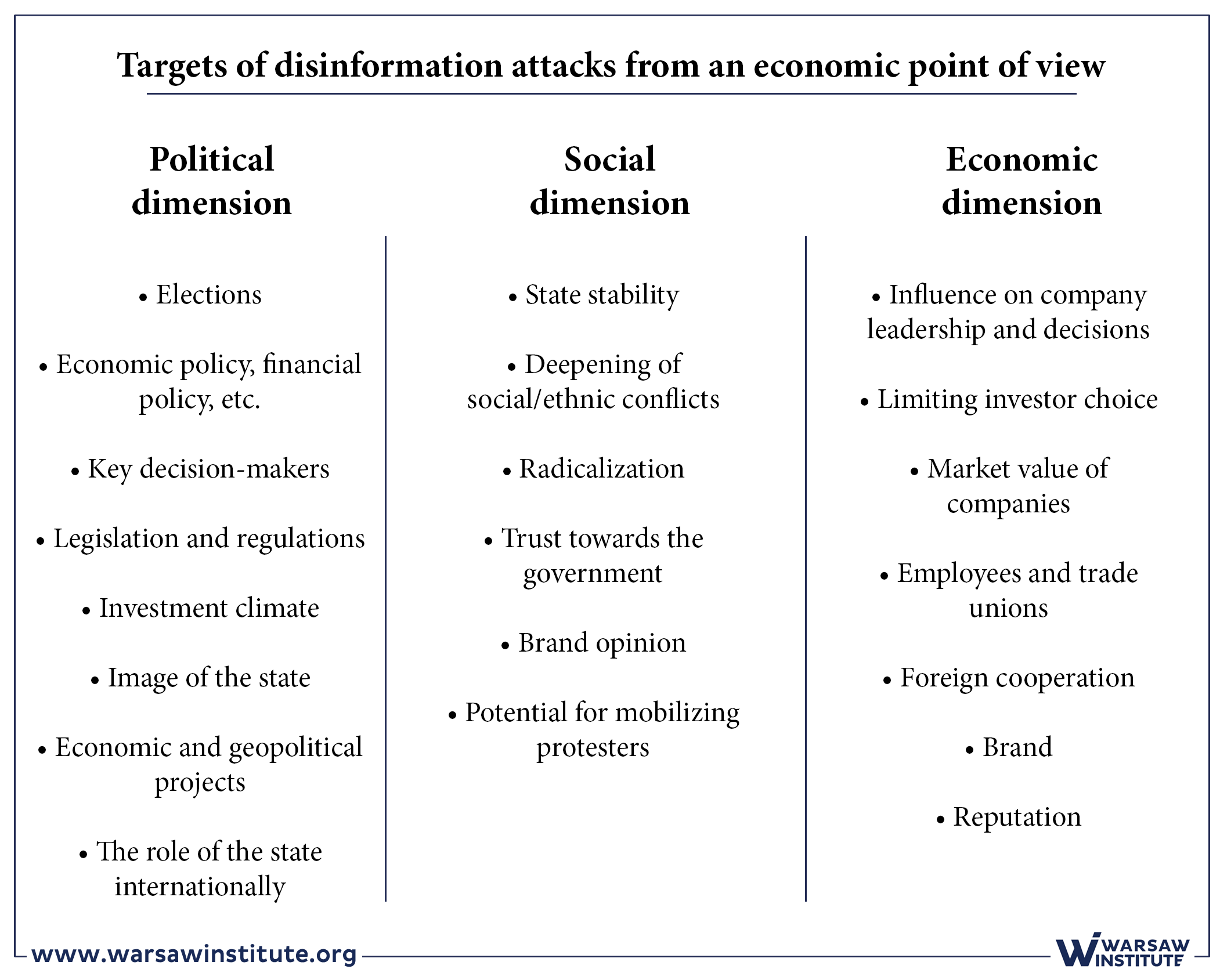

In the case of Russia, generally speaking, disinformation is one of the instruments for pursuing the strategic foreign policy interests of the Russian Federation. The main objective is to strengthen Russia’s international position and extend its reach at the expense of the West, especially in the areas perceived by the Kremlin to constitute Russia’s sphere of influence (i.e. the post-Soviet states). The protection of its economic interests is also fundamental to Russia, including lobbying and manipulation in order to lift sanctions, as well as maintaining Gazprom’s monopoly in East-Central Europe. It’s a priority to weaken or eliminate competition, prevent the implementation of local and international projects (especially when they bypass Russia), which would decrease dependence on the Kremlin and would deprive them of a tool of economic pressure. Russia’s economic interests also include ensuring a market for its energy resources. Russia is interested in taking over (by hostile or conventional means) companies of strategic value for a given country’s economy, at the lowest possible price – and thus, through disinformation and propaganda, Russia attempts to reduce the market value of such companies. With the help of specially-tailored narratives [2] in the information space, including traditional media, new media and cyberspace, attempts are made to manipulate virtually every community in target countries. Is the threat real? According to a CitizenLab analysis, of 218 investigated attacks on unauthorized access to private computers, 21% of attacks were business-related and 24% targeted government representatives.[3] Experience and history teach us, however, that propaganda and the accompanying disinformation have far greater reach and with much worse effects.

Areas of disinformation influence on business

Disinformation is another challenge that must be faced by both private and public entrepreneurs. The first purpose of disinformation is to have a detrimental effect on the reputation and brand of an institution or company. An important element of creating a bad image is a mass campaign of baseless criticism online (trolling), and attributing negative actions to a company for which it is not responsible, causing an exceptionally strong emotional response from society. These accusations may include: breaking the law, environmental damage, corruption, etc., with the goal of inducing a wave of criticism. Damaging a company’s reputation is also achieved by ridiculing, denigrating or compromising the people at the top, perhaps by linking them to institutions, media and people who act as agents of influence. For this reason, the most sensitive area is marketing and PR: sponsoring the wrong events, awarding a scholarship or grant to individuals or organizations involved in extremist activity, or de facto financing disinformation activities online through advertising buys, are just some examples of disinformation operations.

Hostile actions in the information space are also intended to steer the leadership of government institutions towards making decisions that are conducive to the Kremlin’s foreign policy. These may be company-level decisions, such as withdrawing from a project under the influence of false information, but political decisions, such as influencing a given country’s regulations and legislation (or international regulations, such as in the EU). Because Russia’s main export commodities are gas and oil, disinformation often targets projects that diversify the supply of these raw materials. For example, the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline is presented as a German project, while criticism of it from Central Europe is cast as Russophobic hysteria. On the other hand, attacks are aimed at decisions that could limit Gazprom’s monopoly in the region.

Finally, the target audience most vulnerable to propaganda and disinformation is society itself. False information favors confrontational and radical attitudes, and the manipulation of social attitudes. These factors in turn have an impact on the stability of the state and the potential for the mobilization of society, for example: on protests against economic projects [4]. Society also has a direct influence on the direction of state policy as voters and participants in referendums. Disinformation campaigns could be seen during the presidential elections in the U.S. and France, as well as during the referendum in the Netherlands (on the Ukraine-European Union Association Agreement) and the United Kingdom (on leaving the European Union). On a smaller scale, targeted disinformation can hit specific companies and institutions, which may result in strikes (for example, corporate documents that are published, suggesting massive layoffs) or consumer boycotts.

Of course, it should be noted that not every criticism, black PR action or strike is caused by hostile information operations. However, it is quite possible to determine whether something is an organized action or an independent opinion, by analyzing the messages accompanying negative reviews, their time of publication and the tools used.

Disinformation weapons – deception, manipulation, and fake news

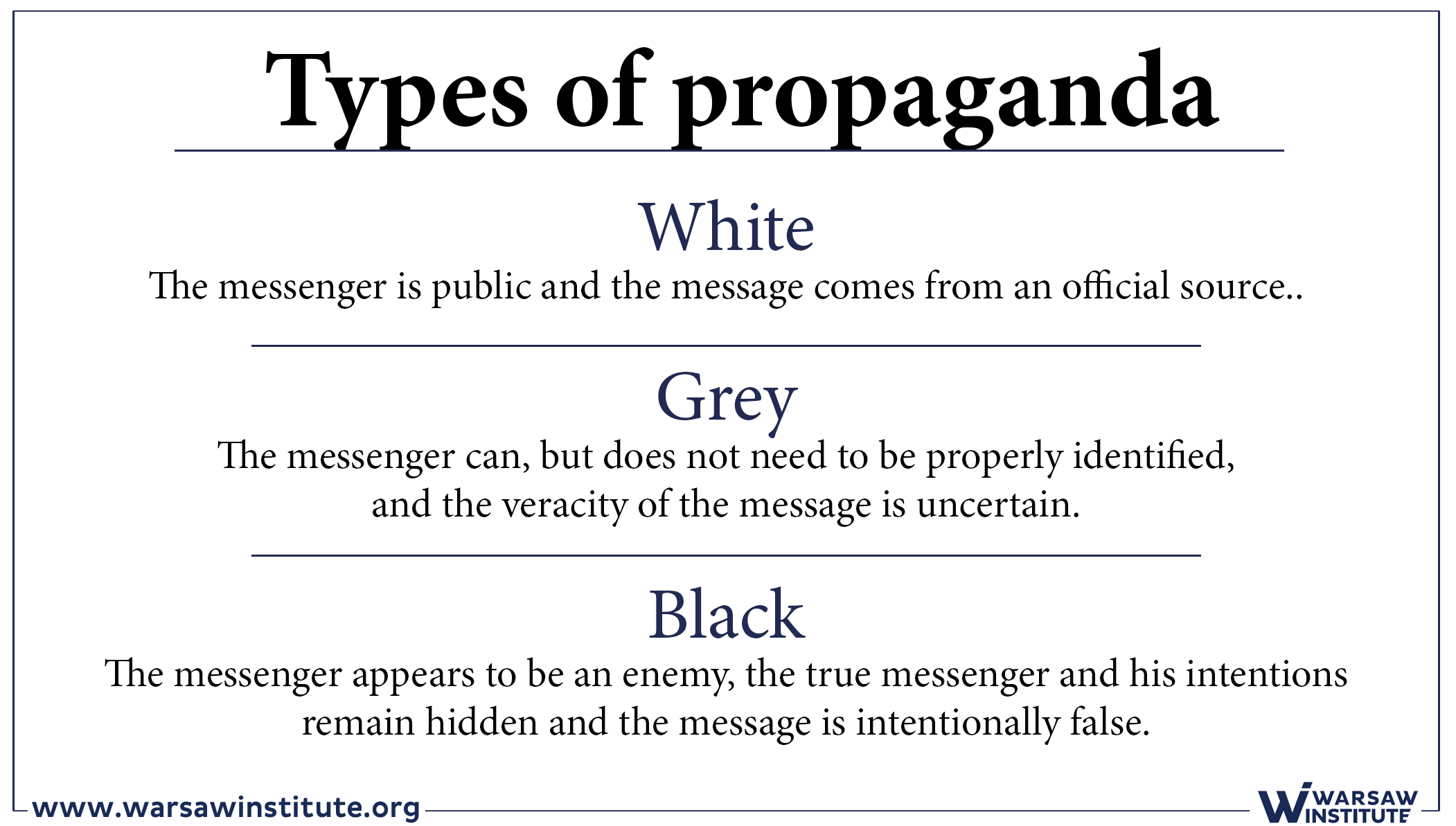

Disinformation, as part of the information war, has a number of tools at its disposal that take advantage of common cognitive defects and the specificity of the modern information environment. Techniques used on a case-by-case basis will vary depending on the target group and distribution channel. It should also be mentioned that Russian intelligence on the way a given country operates, issues important for its citizens, culture, stereotypes and internal divisions, is extremely extensive.

Tools based on deception

The task of media deception provokes desired events that are later exploited by media distribution channels. There are standard forgeries, such as the fabricated letter of Ukraine’s Minister of Finance Natalie Jaresko to U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Victoria Nuland, which requested a postponement of the Dutch referendum on the association agreement with Ukraine.[5] But deception is also created by controlled leaks. These leaks are primarily based on the acquisition of documents through legitimate (official) or illegal (by phishing, cyber espionage or manipulation) sources and then the manipulation of their content by cutting out certain parts of the text and substituting others – or publishing only part of the content without context. An example of a controlled leak was the illegal acquisition of the emails of journalist and Kremlin critic David Satter, and then their publication on the website of the Russian hacker group CyberBerkut, after falsifying the e-mails to persuade the public of Western funding for the Russian opposition, including Alexei Navalny.[6] An example of military camouflaging is the introduction of regular troops under the guise of peacekeepers, as in the case of Abkhazia or South Ossetia (the occupied region of Georgia), as well as “humanitarian convoys” for separatists in eastern Ukraine. This category includes all kinds of fake institutions, such as the “consulate” of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic in Ostrava in the Czech Republic.[7]

Social engineering tools

Such instruments are based primarily on knowledge of the human psyche and the influence of modern technologies on how people process information. The main tool in this category is propaganda: long-term, intrusive interaction, combined with manipulation. A specific variation of disinformation is historical revisionism[8], targeted primarily at states located in the former Soviet sphere of influence in countries such as Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Georgia and Ukraine. As a tool of misinformation, trolling is also used. The task of trolls is to attract attention to a particular topic which their client wants to highlight and bring it into the social or political discussion, manipulating it and promoting narratives beneficial to Russia. In addition to trolling, the popularity of the topic is also enhanced with internet bots. The volume of messaging creates a bandwagon effect – the more people that are able to support a given idea, the more they are convinced that the majority has accepted it. An interesting case are the “bikini trolls” whose profiles contain pictures of young, attractive, scantily-clad women.[9] Their task is to soften the image of Russia, spread conspiracy theories and distract the “target” from work. It is another social engineering tool, taking advantage of the halo effect, that is, adding credibility to a messenger who is physically attractive, clean and neat.

Fake news

Fake news is a synthesis of the two above categories, because it both deceives and influences. It usually also includes elements of truth, because familiar facts facilitate the acceptance of the message. Nowadays it is the most common form of disinformation because of the low costs and the large payoff. One of the examples:

the case of Lisa, a German woman of Russian descent who was supposedly raped by migrants. The Russian media widely covered Lisa’s case. Following broadcasts in social media groups and right-wing media, demonstrations were organized, mobilizing extremists and the Russian-German minority. The Lisa case was also commented upon by Sergey Lavrov, the Foreign Minister of the Russian Federation, who pointed out that the German police were slow to react due to political correctness.[10] This example shows how easy it is to unify specific environments and mobilize them to take anti-government action.

While often downplayed, disinformation and propaganda tend to strike at the weakest point in the functioning of every business – the human element. The problem is also the frenetic pace of technological development, which legislation can’t keep up with, and whose gains can quickly be transformed into tools for further influence. Nevertheless, the effects of disinformation attacks can be reduced by developing counter strategies.

[1]Gerry Osbourne, Strategic Communications: Insights from the commercial sector, NATO Stratcom CoE, April 26, 2017, http://www.stratcomcoe.org/strategic-communications-insights-commercial-sector.

[2] See: Poland Through Eurasian Eyes

[3]Adam Hulcoop, John Scott-Railton, Peter Tanchak, Matt Brooks, and Ron Deibert, TAINTED LEAKS Disinformation and Phishing With a Russian Nexus, The CitizenLab, May 25, 2017, https://citizenlab.ca/2017/05/tainted-leaks-disinformation-phish/.

[4] See: Information Warfare against Strategic Investments in the Baltic States and Poland, page

[5]George Kobzaru, Ukraine struntar and Nederländernas opinion, Pressbladet, April 1, 2016, http://www.svenskpress.se/papers/pressbladet/articles/view/ukraina-struntar-i-nederlandernas-opinion. The article now reads Probably fake news.

[6]Adam Hulcoop, John Scott-Railton, Peter Tanchak, Matt Brooks, and Ron Deibert, TAINTED LEAKS Disinformation and Phishing With a Russian Nexus, The CitizenLab, May 25, 2017, https://citizenlab.ca/2017/05/tainted-leaks-disinformation-phish/.

[7]Michal Lebduška, Lyudmila Tysyachna, The EU entry has been detrimental to Czechia, the fake ‘DPR consul’ Lisková says, StopFake, November 21, 2016, http://www.stopfake.org/en/the-eu-entry -has-been-detrimental-to-the-czechia-dpr-consul-Liskova-says/.

[8] See, Russian Information Warfare in the Baltic States, page

[9]“More on trolls, Internet Trolling as a hybrid warfare tool: the case of Latvia, NATO StratCom CoE, January 25, 2016, http://www.stratcomcoe.org/internet-trolling-hybrid-warfare-tool-case- Latvia-0/.

[10]Stefan Meister, The ‘Lisa’ case: Germany as a target of Russian disinformation, NATO Review magazine, July 25, 2016, http://www.nato.int/docu/review/2016/Also-in-2016/ lisa-case-germany-target-russian-disinformation / EN / index.htm.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.