SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 30 June 2020

Putin’s Constitution

With a constitutional overhaul of the balance of power in Russia, Vladimir Putin is pushing to consolidate his eternal grip on power. As Russia is seeing a slew of rifts in its politics, economy as well as social matters, any attempts to repeat its past ‘tandemocracy’, or the joint leadership of Russia between 2008 and 2012, are considered by the Kremlin as far too risky.

- For roughly two months, thus since Putin’s address to the Federal Assembly, the core question has been not whether the incumbent president is still keen to rule the country past 2024 but rather how he seeks to accomplish this goal. He embarked on the easiest possible way; a proposed constitutional amendment in Russia could see Putin extend his presidency even till 2036.

- These constitutional reshuffles revise both the letter and spirit of the constitution to great extents, virtually making it a novel legislation. Putin could have simply endorsed a law to reset his presidential term clock to zero to achieve what he wanted, yet reshuffles seem far more complex than this. A de-facto change in how Russia is governed would at least be in tandem with a de-jure change, and as such, Putin’s Russia is likely to become but a formality.

- Per the whole constitutional conundrum, Putin creates a system in which the President is the focal element of the country’s political life, with more extensive powers and ever-greater influence on the two houses of the Russian parliament, to the detriment of the Prime Minister and their Cabinet. Likewise, the President will have power over the country’s justice system, and exert full authority over the so-called siloviki, or high-ranked politicians in the top state institutions of Russia.

Whilst addressing the Federal Assembly, in the second part of his speech, Vladimir Putin suggested an array of updates to the Russian constitution in what could be viewed as a mission to get Russia ready once the incumbent leader steps down in 2024. As it turned out only two months afterwards, this came with the Kremlin’s campaign to keep Putin in power. Perhaps Putin’s aides came up with the plan back in January, or maybe later as talks were underway to pass some updates, and when Putin had a better sense of the moods both at home and abroad. Possibly this sought to sow unpredictability throughout the country in a move to inhibit anyone from obstructing an unexpected turn in Russian politics. If Putin had initially planned to step down as President in 2024, he might have succumbed to the pressure of his closest associates who would fear any vehement shifts.

What Putin suggested back in January was too ambiguous and not very binding to make clear that any proposals are yet in limbo and could be modified at any time. Nevertheless, there was something that could hint how the events would eventually unfold. As noted Pavel Felgenhauer, a Russian military analyst, one of Putin’s proposals was to bar anyone from serving for two terms at all, and not just in a row. That was to serve as a loophole that Putin could exploit to remain at the helm for the next twelve years yet with his term limit reset to zero in a move endorsed by the Constitutional Court. That is exactly what took place in March. In some outlandish scenarios, Putin would hover over everything in a different role, as chancellor or chairman of an overarching State Council, but this proved nothing more but a smokescreen, with a blueprint for a brand-new political system that refuted the separation of powers as all were to be in hands of a mighty president.

Like a tsar

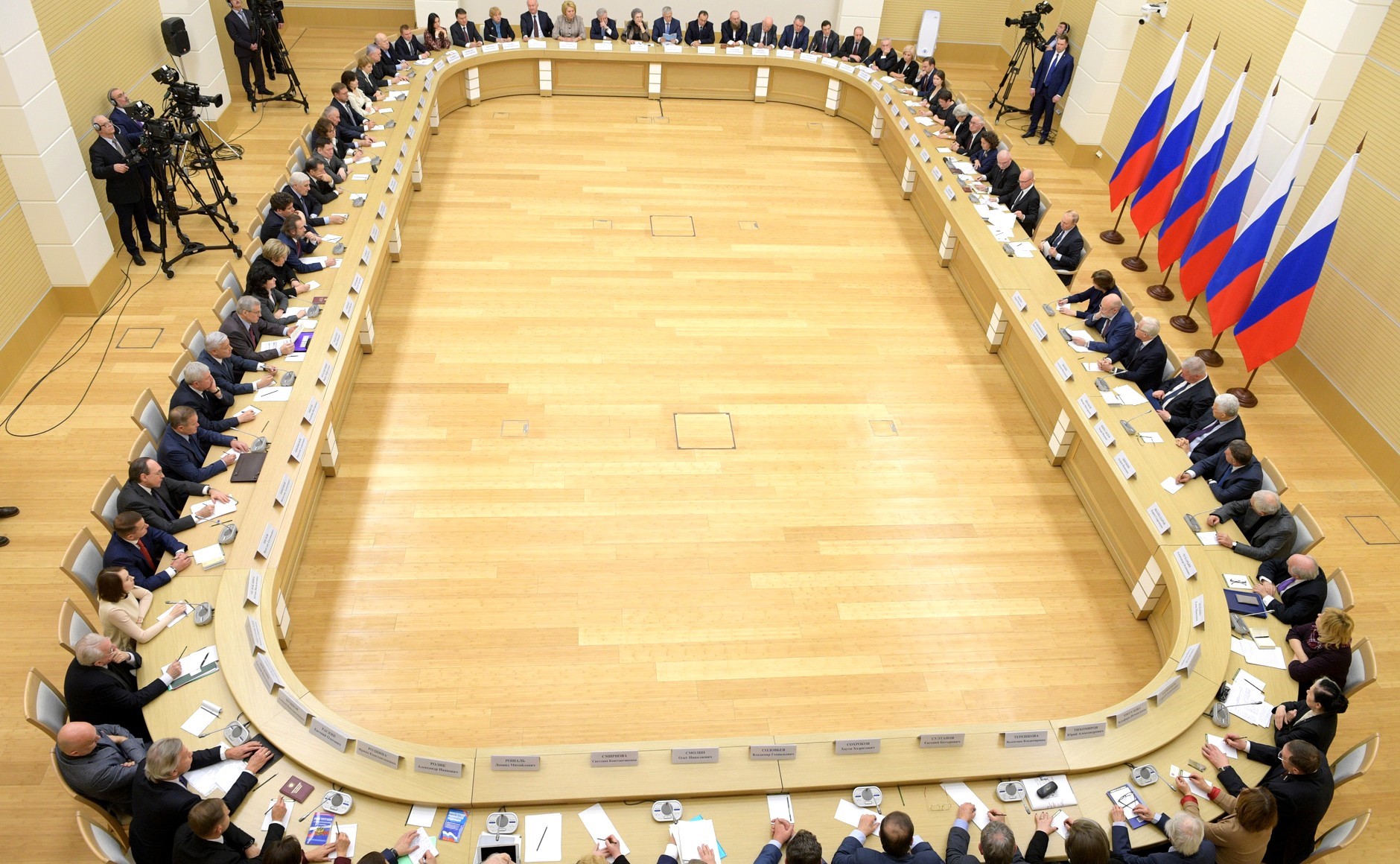

At its very core, the whole mission to amend the Russian constitution is devised to show that incumbent authorities do not impose anything, but listen to the people’s voice before passing new laws. In its 15 January 2020, address, Putin swiftly prompted to establish a working group on constitutional reform that would consist of parliament members, loyal to the ruling party social activists, and notable citizens, including artists or lawyers. It would be tasked with both preparing and reviewing any submitted updates. The working group on amendments to the Russian constitution had received about 900 proposals. On 23 January 2020, Russia’s State Duma adopted in the first reading Putin’s bill on amendments to the constitution. Though the bill was slated to face its second reading on 11 February, State Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin said this would take place no sooner than in late February and early March. A delay may suggest the Kremlin’s troubles or hesitation over what political solutions should be delivered. Until then any reshuffles had been carried out in a fast-track manner[1]. Back in February, Putin met twice with the working group, informing its members on any decisions he had made to either repel or adopt a batch of 100 updates it had picked. On 2 March 2020, Putin submitted the final draft of constitutional amendments that also provided some details on the national vote on the reform and was adopted at first reading.

On 10 March 2020, Valentina Tereshkova, a member of Russia’s parliament and the first woman in space, stood to offer an amendment that resets Putin’s time as president to zero, granting him a chance to run in 2024. After Tereshkova’s “surprise” proposal, Putin announced that he would make his way to the Duma to respond whilst giving green light to any legal updates allowing him to stay in power even till 2036. Tereshkova’s proposal hardly astonished anyone. In his very first press interview after stepping down as Putin’s long-standing aide, Vladislav Surkov on 26 February said that any updates to the country’s constitution would effectively reset the clock on the tenure in office of both Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev. Earlier, the Russian constitution limited the election of one person to the presidency to two consecutive terms, as this is how Putin and Medvedev switched offices. Naturally, neither Putin nor Medvedev will be affected there as their respective term limits will be reset to zero. The number of their presidential terms will be zeroed out after the suggested changes are in force. Furthermore, there is no need to do so –– with a reset presidential term tally, any ex-president could renew his tenure. If Putin won the 2024 vote and then the 2030 ballot, he would become Russia’s longest-serving leader since Peter the Great. Yet in 2036 he would turn 83. If Vladimir Putin stays in power until 2036, he will go down in history as one of Russia’s longest-serving leaders, right before Ivan III of Russia and Ivan the Terrible who ruled Russia for 43 and 37 years respectively. The Kremlin ploy would keep Putin in power longer than Soviet dictator Josef Stalin (29 years), as well as a number of Russian tsars, including Nicholas I (29 years), Alexei (30 years), Michael (32 years), Catherine II (34 years), and Peter the Great (35 years).

The State Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament, on 10–11 March formally reviewed the second and the third reading of constitutional reform legislation. It passed the legislation in a unanimous 383-0 vote, with 43 abstentions. Also on 11 March, Russia’s Federation Council approved a bill amending the country’s constitution. Between 12 and 13 March, all of Russia’s regions endorsed new amendments to the constitution, a step that opens the possibility of Vladimir Putin remaining in power, as two-third out of all 85 regional parliaments (including Russia-imposed legislatures in Crimea and Sevastopol) gave their nod to the draft bill. Russia’s Constitutional Court ruled on 16 March that the constitutional amendments bill proposed by Putin are in line with the country’s constitution. As for efforts to push the law to reset Putin’s presidential term clock to zero, Russian judges ruled that they should pose no harm to the country’s core constitutional features as long as these are shielded by “Russia’s well-developed parliamentary system of government, its genuine multipartyism, political competition and an effective model of separation of power and the rule of law“. Formally Russian lawmakers have not adopted a completely new constitution, though the recently submitted proposals are so extensive that form novel legislation, thus the Putin-style constitution. The Kremlin has opted for a bundle of formal manoeuvres to update the constitution while not violating its provisions. As Russian officials are only empowered to amend a number of vital chapters with a wholly new constitution, some relevant provisions were simply inserted into another chapter. In the law titled ‘On Improving the Regulation of Certain Aspects of the Organisation and Functioning of Public Authority’, Russian lawmakers passed a package of laws to the 1993 constitution.

Superpresidential republic

Hence, one would contemplate, what do constitutional amendments change? What are the most important revisions? Putin consolidates his centralised grip on power by exerting direct authority over the government. It is getting weaker, and so is the country’s justice system. The government is de facto made for the President’s indefinite control, with the Prime Minister being stripped of their right to shape the direction of the Cabinet’s work. While part of the siloviki reports to the President, another group is subordinated to the Prime Minister. Also, these are named differently. Ministers tasked with both power structures and foreign affairs will be appointed by the President after consultations with the Federation Council. Though much is said about extending the parliament’s power, that is nothing but an illusion. The amendments suggest increasing the presidential share in the Federation Council, the upper house of the Russian parliament, to 30 people, from no more than 17 at the moment. Of them, seven officials, including former Presidents of the Russian Federation, will get the right to become life members of the Federation Council, while all members of the Russian Federation Council will be officially referred to as senators. The State Duma, which in the past gave its “consent” to the appointment of the Prime Minister, will now “approve” the candidacy. Also, the parliament is giving up some powers, as Russian lawmakers will approve cabinet members, too. Not only does the president retain its weapon –– the right to dissolve the State Duma if it rejects the suggested candidate three times –– but he also wins a new reason to disband the lower house. Under a new law, if the State Duma does not agree to more than one-third of the proposed candidates, then the president has the right to dissolve the lower house. The proposed amendments would give the president the right to dismiss the Prime Minister alone, allowing the cabinet to remain in place and continue to work. Another provision says that the president will take “general charge” of the work of the government.

The number of judges in the Constitutional Court will be reduced from 19 to 11, and its power of attorney will be extended. The justice body will be given the right to check whether a new law is compliant with the constitution and perhaps also to repel any draft laws and other normative laws. The President will also have the power to submit a request to the Federation Council for dismissal of Presidents, Vice-Presidents, and judges in the Constitutional Court and Supreme Court, and certain lower-level courts. At the moment, the upper house is empowered to remove judges yet only at their own request[2]. The president will have greater control over the prosecutor’s office too. Now both the country’s chief prosecutor and their deputies are appointed with the consent of the upper house of the Russian parliament. In line with the revised constitution, the president has the right to make the decision himself after consulting the upper house (Article 129).

A new constitutional status and extensive formal powers were vested in the State Council, a body that was created back in 2000 under Putin’s executive order. Shortly after its inception, it was to bring together senior officials in the regions once Putin has amended the powers of the Federation Council that used to house Russian governors. The State Council, an advisory body to the President, is made up of the heads of regions, Speakers of the two houses of parliament, the President’s plenipotentiaries in the federal districts, and heads of parliamentary factions in the State Duma. Then, what are the new competencies for the State Council? If to be interpreted quite broadly, these would empower the body with massive powers that could mirror those of the President. The State Council has a clear mission: to ensure the harmonious functioning of the public authorities and co-operation between them, as well as to define the priorities of domestic and foreign policy and of the country’s social and economic development. Its status is to be provided for in detail in an act of law. It could be said that Putin is saving the fact amid what was discussed back in January that he would keep power as the head of the mighty State Council. All in all, Russian officials opted for the simplest way by allowing Putin to stay in power while elevating the status of the State Council, at least formally.

As early as in January and sometime after while talks were underway on the constitutional reboot, it was clear that with an updated constitution, the President wins wider powers. There is just one restriction –– as the President cannot reject candidates for cabinet members already approved by the State Duma. Yet this hardly matters at the moment as the Prime Minister submits a list of their Cabinet members to the State Duma. The President of the Russian Federation will still choose the Prime Minister himself. In that, the President wins some extra rights. He can veto a draft bill while signing it and submit it to the Constitutional Court that is empowered to sustain the leader’s veto. So is he capable of relieving Constitutional Court judges from their duties (including the Federation Council) or forming the State Council. With the reform, there will arise further centralisation of power while the remains of weak local government will no longer exist. The amendments include a novel principle of a “single public authority system” of various levels, from regional to federal while allowing the President to ensure harmonious operation between any authorities. A new constitutional duty is to “maintain public order and harmony in the country,” a step toward the increased authoritarianism.

A rigged social pact

From the very beginning, Putin’s ambition was quite simple: to portray the amended constitution as a deal between him and Russian society. In doing so, he set up a showy working group while other officials pushed with populism-infused reboots, with a nationwide referendum as the cherry on the top. In his January address, Putin delivered a set of costly social promises, some of which are to be included in the revised constitution. He backed a proposal to include social guarantees in the constitution: index pensions and keep the minimum wage no lower than the subsistence rate in Article 75 of the Russian constitution. As indicated, pensions are to be adjusted to inflation no less than once a year. It costs little to insert a wide range of promises to the country’s constitution. Whether these are fulfilled depends on a set of detailed laws. If the amendment is added, the constitution appears on the “protection of family, motherhood, fatherhood, and childhood” while “defining heterosexual marriage as the only true form of wedlock.” An amended Article 68 mentions the Russian language as the country’s official language, thereby beefing up the course that Putin long wished to embark on. In a novel constitution, lawmakers enshrined a promise to throw support for “Russian countrymen abroad” while referring to the Russian nation as “state-forming“, with a mention of God, tradition, or the Soviet legacy. With these amendments, Russian officials have a twofold goal: to win conservative voters and to formulate the Kremlin’s anti-Western and great-power narrative, as is the case of yet another new provision that pays respect to defenders of the homeland and obliges the Russians to acknowledge what was named as the “historical fact.[3]” The latter factor comes evident if to take a closer look at the updates on Russia’s stance on its international obligations, with an amended Article 15 on supreme legal force of the rules of the international treaty. Putin seeks to reboot the constitution to make international laws binding as long as they “do not violate the rights and freedoms of Russian citizens.” Russian institutions will feel free to ignore any international laws and deals yet in a constitutionally justified move[4]. Russia will not comply with obligations imposed by international courts either, including arbitration tribunals if they constitute “a violation of the foundations of legal public order of the Russian Federation“. Besides, it is also prohibited to take or incite any action aimed at disbanding any part of Russia’s territory. Thus the annexation of the Crimea has been declared irreversible.[5]

In line with the 11 March law, the whole process will reach its apex only after a nationwide vote on a set of constitutional amendments. While saying “yes” to new social benefits or enshrining God in the Russian constitution, Russian citizens cast a ballot for Vladimir Putin and his life-long rule. There is no mandatory approval threshold for adopting these changes; the amendments are already considered valid and will come into force if supported by the majority of voters. It is not a referendum; it is a completely novel creation. On March 25, Putin told citizens that a nationwide plebiscite on changes to the country’s constitution, which was scheduled for 22 April, would be postponed to help curb the spread of the novel virus. Therein a legal paradox occurred, according to Tamara Morschakova, a former judge of the Constitutional Court and one of Russia’s most renowned lawyers. As she argued, the whole array of constitutional amendments stipulates also how these will come into effect. In consequence, there are now two constitutions in Russia: the “old” one and its revised version. While no changes were made in the order as specified in the law, under Articles 134 and 136 of the previous version of the Russian constitution, the updates should be already legally binding. But state authorities see no legal dispute[6].

Russian President Vladimir Putin on 1 June 2020, set a 1 July 2020 date for a nationwide vote on constitutional amendments allowing him to extend his rule. Hence, Wednesday 1 July 2020 will be a day off work for all Russians. Starting from 25 June, voters will have a chance to cast ballots. In some of the country’s regions, perhaps also in Moscow, voters will be allowed to vote online. A new law on amending Russia’s election legislation stipulates that voters can cast their ballots by mail or in a remote online vote amid the epidemic. As such, authorities will be able to apply vote-rigging mechanisms, and will likely use special mechanisms to ensure safety for the public. Surely the Kremlin is eyeing a high turnout to further strengthen Putin’s presidency. According to Russian pollsters, even independent ones, it is likely to hit more than 50 percent with most “yes” votes[7].

In effect, the amendments are now becoming a fact. Two days before Putin’s decision, Pavel Krasheninnikov, the co-chair of the working group on constitutional amendments, said that some of the constitutional updates, earlier approved by both the State Duma and the Federation Council, are already in place. “It happened that some of the constitutional amendments are already in force,” he said. They serve as a legal basis for both new federal laws and presidential decrees. For instance, Vladimir Putin on 21 May proposed a new bill on patriotic education. The same was true to a set of social promises included in the bundle of constitutional updates. These were changes being voted at the 22 April nationwide referendum, rescheduled amid the coronavirus pandemic[8].

Racing against the clock

Russian officials did not push for the constitutional reform because of Moscow’s failed attempts to absorb Belarus and offer Putin a beefed-up role as the leader of a new unified state. A turning point was Putin’s January address that made the president’s way to a new political system on the banner of stability, unity, order, and social security. Subsequent changes are introduced in a somewhat hectic manner. The country’s officials were pushing for them even before the coronavirus pandemic took a firm grip on whole Russia, and made more intense efforts only after announcing a nationwide vote on constitutional changes in late June and early July. This portrays how Russian lawmakers breached the existing procedures to adopt any constitutional updates, and imposed what they referred to as a “nationwide vote” instead of a referendum.

Why then the accelerated pace of action? With the whole process going on and endless talks on how these updates would look like, Russian political elites could somewhat feel nervous. Among those most interested in securing Putin’s solid power grip are people belonging to his inner circle. These are the “state oligarchs”: heads of state-run firms or owners of private companies yet with close links to the Kremlin. In the second group, there are “political technocrats”: Sergey Kiriyenko, Sergei Shoigu, and Anton Siluanov. But those who have most to lose are the siloviki, alongside such businessmen as Gennady Timchenko, Igor Sechin, or Arkady Rotenberg. They are involved in all Putin’s crimes, serving or having served as heads of Russian special services. If the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the country, Putin’s popularity ratings could be in danger, as they have recently dropped compared to what they rose in 2014 in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine[9].

The fall in Vladimir Putin’s popularity ratings is bucking the trend. The pandemic and much-criticised state policy, including Vladimir Putin’s self-isolation from Russian society, have created a less comfortable environment for the Kremlin while speeding up some dangerous shifts. What is particularly grappling for Kremlin officials is that Putin’s traditional voters, who have hitherto labelled themselves as “apolitical”, are becoming more and more interested in domestic affairs. With their growing interest in politics and chiefly a critical approach towards state officials, Russian society somewhat comes as more mature than before. The Russian state has failed the coronavirus test, chiefly amid the autocratic personalised model, in which far too much depends on the President. Importantly, unlike before, Putin did not find a scapegoat whom he could blame for the coronavirus crisis, nor did he shift full responsibility to the Prime Minister or local officials. Back in late April, popularity polls found that Putin’s approval ratings went down, unlike was the case of Western leaders. While the approval ratings of most Western leaders have risen amid the new coronavirus pandemic, Vladimir Putin’s ratings are consistently falling. State propaganda solutions proved ineffective, sociologists say. There are more and more people criticising the authorities in virtually all social groups throughout Russia. Finally, Putin’s self-isolation is apparently being judged not as responsible behaviour. Educated urbanites have long been against Putin’s rule. He could ignore them as long as he enjoyed support from the working class, which has always been a pillar of the regime. The pandemic has indeed to an extent changed the status quo by means of seeing more and more Putin’s voters declaring themselves as interested in politics, and with this, more critical toward the regime. However, their objection stems from other reasons than that of urban residents. Those who in the past voted for Putin are now irked by the president’s weakness as the incumbent leader is inept to take adequate steps[10].

Constitutional changes are imbued with ideology too, with both anti-liberal and anti-Western features. In a sense, it would seem that Vladimir Putin seeks to reintroduce nineteenth-century Tsarist methods, albeit in a revived version, to make society rely upon Orthodox, Tsarist autocracy, and the very sense of Russianness. In it, constitutional updates refer chiefly to the state model, with a beefed-up role of the President. In a slew of other amendments to the country’s constitution, lawmakers promote a proclamation of “Russians’ faith in God” and look to reinforce “the state-forming nationality”.Putin’s constitution pushes Russia out of the Western world while inserting it into the Eurasian universe, also through its rebuff of the rule of law, thus a principle having its roots in both Greek philosophy and Roman law. It would not therefore seem an exaggeration to suggest that the regime’s hybrid authoritarian rule is now sliding into its hardened version. The whole reform is unlikely just to zero out Putin’s tenures in office as that would be done with a set of constitutional changes. The Russian leader has the ambition to go down in history while consolidating his grip on power by staying on in post and legitimising any changes he had pushed forward since 2000. Formally, whilst the 1993 constitution applies yet with some reboot, this move morphs into a completely new one. After all, it would seem that the incumbent Russian President looks to have his constitution taught in history textbooks alongside those by Lenin, Stalin, Brezhnev, and Yeltsin.

Author:

Grzegorz Kuczyński – Director of the Eurasia Program, Warsaw Institute

Grzegorz Kuczyński majored in history at the University of Bialystok and graduated from specialized Eastern studies at the University of Warsaw. An expert on Eastern affairs, he long worked as a journalist and political analyst. He is the author of many books and publications on the inside scoop of Russian politics.

[1] https://warsawinstitute.org/putin-supreme-leader-slowdown-russias-constitutional-overhaul/

[2]https://tygodnik.tvp.pl/46227156/siedem-godzin-ktore-wstrzasnely-rosja-czyli-jak-putin-zostaje-dozywotnim-przywodca-narodu

[3]https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/komentarze-osw/2020-03-13/wieczny-putin-i-reforma-rosyjskiej-konstytucji

[4]https://tygodnik.tvp.pl/46227156/siedem-godzin-ktore-wstrzasnely-rosja-czyli-jak-putin-zostaje-dozywotnim-przywodca-narodu

[5]https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/komentarze-osw/2020-03-13/wieczny-putin-i-reforma-rosyjskiej-konstytucji

[6]Иван Преображенский, Комментарий: Поправки в Конституцию РФ заработали без народного голосования, Deutsche Welle, 02/06/2020

[7]https://warsawinstitute.org/putin-life-kremlin-wants-nation-support-now/

[8]https://ria.ru/20200530/1572221500.html

[9]https://warsawinstitute.org/putin-seeks-stay-power-unlawful-constitutional-amendment/

[10]https://warsawinstitute.org/coronavirus-russia-putin-ratings-problem/

The concept of analytical material was created thanks to co-financing from the Civil Society Organisations Development Programme 2019.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.