THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ON VISEGRAD GROUP COUNTRIES. The aim of the project is to monitor the activities of the PRC in relation to the V4 countries – Poland, Czechia, Hungary and Slovakia. The project is funded by the International Visegrad Fund.

Date: 29 January 2021

Author: Paweł Paszak

Poland-China Relations in 2021: Current State and Prospects

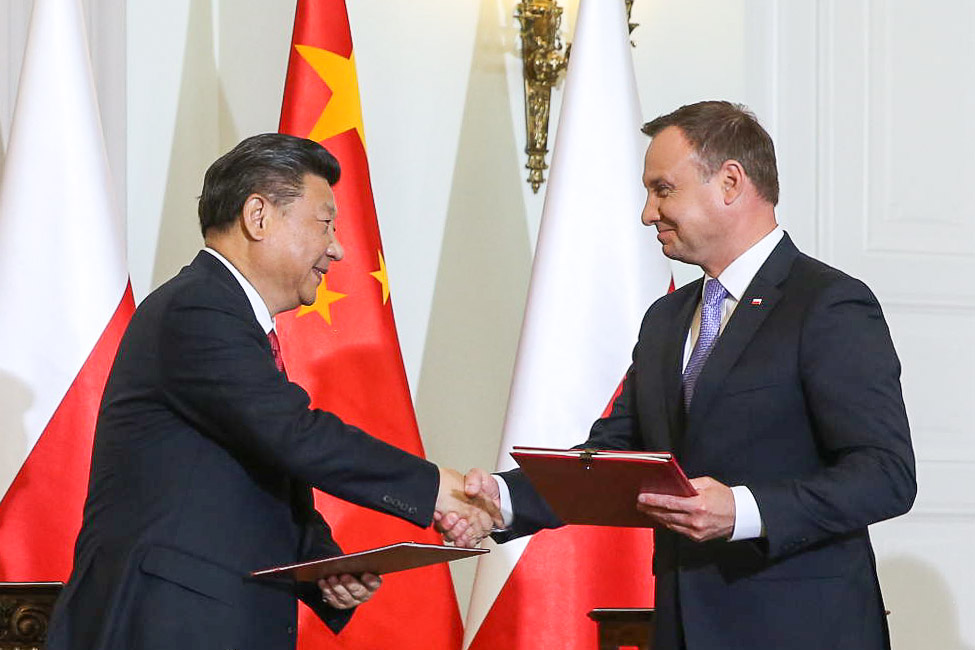

A telephone conversation between Polish and Chinese Ministers of Foreign Affairs Zbigniew Rau and Wang Yi took place on January 22, 2021. The Ministers discussed plans for 2021, including the organization of a summit of the 17+1 initiative. Furthermore, Wang Yi expressed his desire to “deepen trust” in Poland-China bilateral relations, which “should not be influenced by a third party.” Despite growing trade and good relations between the presidents of the two countries, communication between Warsaw and Beijing has stalled for some time. Following a period of dynamic development of relationships between 2008 and 2016, the cooperation has weakened under the rule of the United Right (Polish: Zjednoczona Prawica). This is due to a disappointment with the lack of significant progress of the Belt and Road Initiative, the 17+1 format as well as limited access to the Chinese market for Polish manufacturers. The confrontational policy of Donald Trump’s administration towards China, described as the biggest threat to the United States’ position, has been an additional obstacle. Poland, most likely under pressure from Washington, rejected the possibility of greater Chinese involvement in the construction of the Central Communication Port (CPK) and took steps to limit Huawei’s access to the 5G infrastructure market.

Poland, the USA and the Case of Huawei

One of the priorities of Donald Trump’s diplomatic agenda in Europe was to exclude Huawei from the construction of the European 5G network. China’s systemic rivalry with the United States has had and will continue to have a significant impact on relations between Poland and the Middle Kingdom. For years, the authorities in Warsaw have been striving to strengthen the US military presence in Poland and the region. Efforts made by successive governments were crowned with the signing of an Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement on August 8, 2020. However, the matter of limiting cooperation with Huawei and China was a part of these negotiations. On September 2, 2019, during the visit of US Vice President Mike Pence to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II, Poland and the US signed an agreement to cooperate on 5G technology. In turn, on September 7, 2020, the Polish Ministry of Digital Affairs published a draft amendment to the Act on national cybersecurity system, which took into account the matter of accessing the 5G market by external providers. The draft assumes an assessment of the provider and the possibility of excluding it, for instance, due to “threats to the implementation of allied and European commitments” as well as “an analysis of threats to national security of economic, counter-intelligence and terrorist nature.” These provisions, although they do not mention the Chinese firm, provide the basis for preventing operators from using its equipment. The draft has not been adopted yet therefore it is possible that the government softens its stance. Given the poor prospects of Huawei’s growth in Poland and Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the authorities in Beijing will most likely try to convince the countries of the region to allow the company to participate in the establishment of 5G networks.

China-EU Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI)

One of the issues raised in the discussions between Warsaw and Beijing will be the position of the Polish government towards the adoption of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), which aims to facilitate European investors’ access to the Chinese market. On December 30, the European Commission announced that the negotiations over the Agreement have concluded. Poland was among the countries that raised objections to such a quick conclusion of the negotiations. On December 22, Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Zbigniew Rau underlined on Twitter that “Europe should seek a fair, mutually beneficial Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China.” Additionally, he stressed that “we need more consultations and transparency bringing our transatlantic allies on board. A good, balanced deal is better than a premature one.” The Minister’s argumentation indicates that Poland’s reluctance was caused by concerns about the consequences that the Agreement would have on relations with the United States. The doubts of the Polish government should be assessed as justified because the adoption of the Agreement will certainly hinder the opportunity to reset EU-US relations. The breakthrough in negotiations overlapped with an unusually turbulent transition of power from Donald Trump to Joe Biden and the end of the German Presidency of the Council of the European Union. The coincidence of these events indicates Beijing’s attempt to take advantage of the situation and exclude Europe from the efforts to economically balance China. The CAI will enter into force once it is approved by the European Parliament – the European Commission expects it to happen by the end of 2022. The United States will try to use this time to convince allies to change their position. On the other hand, China will attempt to maintain the status quo, making it difficult for the EU to pursue a more assertive policy.

17+1 and the New Silk Road

At the beginning of the previous decade (2010-2020), Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) still had very high hopes for China. Following the global financial crisis and the European debt crisis, an increasing number of states started to perceive China as an alternative to the West. A partial reevaluation of policy was motivated by the desire for independence from one economic partner, in the case of Poland and CEECs – Germany and the European Union. Diversification of export destinations and sources of investment was, from this perspective, a natural way to increase the level of economic security of the country. This phenomenon was noticeable also in the case of Poland where the potential benefits of economic cooperation with China included mainly its huge market and infrastructural potential. Shortly, Polish-Chinese relations intensified in parallel with the announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 and the launch of the 16+1 format in 2012 (17+1 since May 2019). A strategic partnership between Poland and China was signed in 2011, and later, in 2016, enhanced into a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. Another summit of the 17+1 format – the first one under President Xi Jinping – is expected to take place in February 2021. It is likely that the discussions will address the following issues: Huawei’s access to the 5G infrastructure market, the attitude of CEECs towards the adoption of the CAI agreement as well as the state and prospects of economic cooperation. Despite political will on both sides, there is little FDI coming from China, less than from South Korea and Japan. This is due to a small number of innovative companies in the high-tech sector, which are the main focus of Chinese investors. Following the CCP’s top-down restrictions on capital outflows from China in late 2016, there is little chance that this state will change.

The situation was similar in the infrastructure market, where for a while China was perceived as a potential alternative to the capital from the European Union. These assumptions were quickly disproven when it turned out that the Chinese model of financing projects cannot compete with EU mechanisms. Recently, however, the Chinese companies are noticeably active in road and rail tenders. In August 2019, the Chinese firm Stecol won a tender for the construction of a section of the Łódź bypass (S14) worth PLN 724 million. Furthermore, in June 2020, a Polish-Chinese consortium won a tender to build a section of Rail Baltica (Czyżew-Białystok) worth about PLN 4 billion. In December 2020, it was announced that Stecol, with a bid of PLN 530.8 million, had been selected to build the section of the A2 highway (Mińsk Mazowiecki-Siedlce). These examples prove that Chinese companies are becoming increasingly effective in competing for infrastructure projects in Poland and the European Union.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission. Support

In terms of trade, for years there has been a noticeable growth both in export and import. According to the Chinese customs office, in 2020, trade between Poland and China exceeded USD 30 billion for the first time in history, with a year-on-year growth rate of 12 percent. China sold USD 27 billion worth of goods to Poland and purchased USD 4.3 billion worth of products from it. As a result of such a disparity, Poland recorded the highest trade deficit with China, which amounted to USD 22.4 billion. At first glance, high and persistent negative trade balance of Poland seems to be a negative phenomenon. However, these calculations do not reflect the complexity of trade flows, which are fragmented in the face of global value chains. Maciej Kalwasiński, an analyst of bankier.pl, underlines that “the growing trade deficit with China is not relevant,” pointing out that Polish industry produces intermediate goods, which are later exported from Germany as final products and are included in trade of that country with China. Estimates presented by Łukasz Ambroziak of the Polish Economic Institute (PIE) show that due to such interdependencies, Poland’s actual trade deficit with China is 40 percent lower. The above observations are supplemented by another factor mitigating the unfavorable statistics, namely the consumer convenience. Thanks to the availability of a wide range of competitively priced products imported from China, Poles can benefit from a larger quantity of consumer goods, whilst businesses have to work hard in order to attract customers.

The Silk Railroad is also one of the constructive elements of economic relations. As a result of the pandemic and the disruption of maritime transport associated with it, rail freight traffic between China and Europe has reached record heights. According to Xinhua News Agency, 12,400 freight trains travelled between China and Europe in 2020 – 50 percent more than the year before. The Małaszewicze transshipment area, located near the border with Belarus, played a significant role in this project. It allows the rail–rail transshipment between trains with broad gauge, used in the former USSR (1520 mm, 4 ft 11.85 in), and trains with standard gauge, common across Europe (1435 mm, 4 ft 8.5 in). The existing infrastructure does not meet the demand imposed by the increased number of incoming freight trains therefore traffic congestion is a common problem. For years the traffic flow has been improved, for instance, through the modernization of the E20 line, construction of a new bridge over the Bug River and expansion of the railroad infrastructure in Małaszewicze. Moreover, on January 26, the Polish Ministry of Infrastructure announced that it will spend PLN 4 billion (EUR 1 billion) on the expansion of the logistics park. The structural problem associated with the Silk Railroad is the role of Poland as the transshipment hub. The final destination of the majority of trains going to Europe is its western part and a significant number of them returns empty to the Middle Kingdom.

The Russian Factor in Relations Between Poland and China

As a result of Poland’s strategic location on the eastern flank of NATO and the European Union, the authorities in Warsaw consider the possibility of an armed conflict with the Russian Federation more often than Western European governments. A potential Russian attack on the Baltic States, and later also on Poland, is regarded as the gravest threat to national security and stability in the region. This perception was confirmed by the armed conflicts in eastern Ukraine (2014-2021) and Georgia (2008), which led to the illegal annexation of Crimea and the establishment of façade quasi-states, completely dependent on Moscow’s policy. This is compounded by regular disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks on Poland and other states in the region. As a result of the outlined factors, the Russian factor plays a crucial role in Poland’s relations with all key partners (the USA, Germany, NATO and the EU). The Russian Federation should also be taken into account with regard to relations with China, for which it is a vital partner in multiple domains. Beijing and Moscow maintain a deep strategic cooperation while their perspectives on the international order remain convergent in many ways. Both countries aim to weaken the American influence in Europe, which is perceived as an obstacle to the implementation of the Chinese and Russian interests. The authorities in Beijing are aware that the growing disproportions in the capacities of both countries is a source of concern for Moscow, for which the belief in its power status is the basis of national identity. For this reason, they avoid excessive engagement on the territories that Russia considers to be its sphere of influence. China has not expressed support for the aggression against Ukraine, being consistent with the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, but it also has not openly condemned it. Moreover, the Ukrainian crisis was followed by an intensification of relations between Moscow and Beijing, which shows that this matter was rather insignificant. In the case of the protests in Belarus in 2020, Beijing expressed support for a resolution of the conflict by Alexander Lukashenko alone, at the same time leaving the settlement of the Belarusian issue up to Moscow. This indicates that in the future China’s position will not be a major obstacle to Russia’s aggressive actions in Eastern Europe. From the Polish standpoint, the impact of China’s policy in this area should be assessed as unfavorable because it leads to a tacit acceptance or support of the revisionist actions of the Russian Federation in the post-Soviet area and Eastern Europe. The vision of international order promoted by Beijing and Moscow assumes a weaker American presence in Europe, and therefore the erosion of the functioning of NATO, which is the foundation of Polish security policy. Consequently, in the long term, the rise of China’s power and the evolution of the international system, provided there is a continuity in relations between Beijing and Moscow, will have a negative impact on Poland’s security environment and the possibility of promoting the values that formed the basis of the European project.

Conclusions

The coming years will be difficult for the relations between Poland and China. The pro-American attitude of the authorities in Warsaw will make it extremely difficult to thaw relations with Beijing on the political level. Due to the importance of NATO and the transatlantic relations, it should be expected that Huawei’s role will be gradually limited. Poland will probably be one of the main states advocating for consultations with the US on the adoption of the CAI. Simultaneously, the skepticism is growing among the intelligence and analytical communities, which are increasingly reluctant to potential educational and technological cooperation, seeing it as a way for the PRC to build its influence. The similarity of Moscow’s and Beijing’s perspectives is yet another reason hindering a potential improvement of political relations. All this is compounded by the incompatibility of core values underlying the two political systems. In Poland, the conservative Catholic parties (apart from Confederation) and the left-liberal parties condemn human rights violations in China. Despite these differences, trade and freight flows within the framework of the Silk Railroad are expected to grow. Infrastructure tenders, in which Chinese companies are increasingly becoming active and effective, are also an area that should be closely monitored.

This article is a part of the project “The Role and Influence of the People’s Republic of China on Visegrad Group Countries” funded by the International Visegrad Fund.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.