SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 24 May 2021

Author: Rafał Zgorzelski, PhD

Witold Pilecki – a Flawless Hero

On the 120th anniversary of Witold Pilecki’s birth and the 73rd anniversary of his martyr’s death, it is vital to recall one of the most heroic and outstanding soldiers of the Polish armed underground resistance movement during World War II.

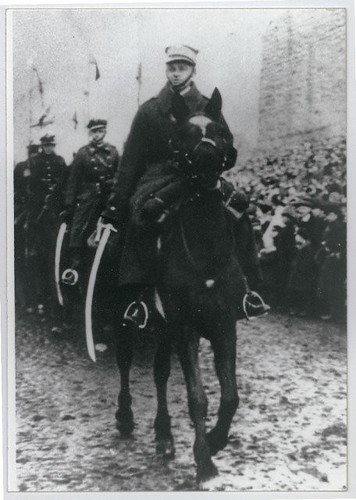

- In the late summer of 1937 Pilecki was the commander-in-chief of the Lida Cavalry Squadron at the 19th Infantry Division. He also took part in drills under General Stefan Dąb-Biernacki.

- Pilecki volunteered to allow himself to be captured by the occupying Germans to smuggle himself into the Auschwitz concentration camp to draw up reports detailing Nazi atrocities at the camp and establish an underground resistance movement.

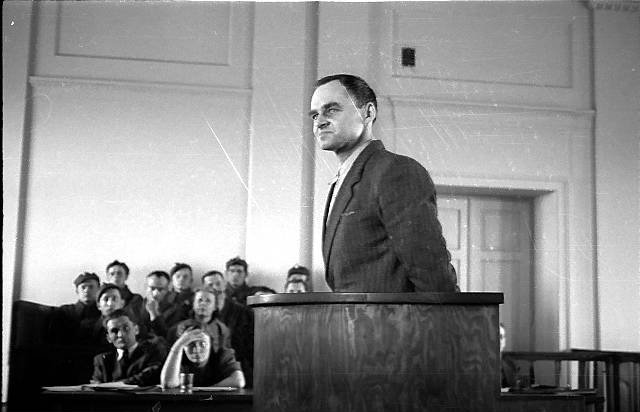

- He was arrested on May 8, 1947, and thrown in a Mokotów jail. While interrogated, Pilecki sought to claim full responsibility for what did the anti-Communist underground movement. Pilecki’s interrogation was personally supervised by Józef Różański, who headed the Investigative Bureau at the Ministry of Public Security.

Witold Pilecki was born on May 13, 1901. His grandfather Józef had been forcibly resettled to Siberia for participating in the January Uprising, from where he did not return until 1871. Witold’s father, Julian, was a graduate of the St. Petersburg Forestry Institute, then an assistant, and––upon promotion––a forest inspector in Olonets, Karelia, where Witold was born to him and his wife Ludwika, née Osiecimska. Witold’s mother was the daughter of a forest inspector; his brothers, Hipolit and Hieronim, fought in the January Uprising––just like Witold’s grandfather Józef.

Ludwika exerted a huge impact on Witold, who from his early days had shown a vivid interest in military games, music, poetry, and drawing. The mother told him and his siblings––sisters Maria and Wanda and brothers Jerzy and Józef (who died at 5)––stories about the January Uprising, Mikhail Muravyov (known under the moniker “Hangman”), Vilna, or forfeiting private property after the insurrection, a repercussion that affected the Pilecki family too.

In 1910 Witold moved with his mother Ludwika Pilecka and siblings to Vilna, looking for better education, while the father remained in Olonets. While there, the young Pilecki attended a local school of commerce; at 12, he started attending clandestine self-education clubs, and in 1913 he joined the underground Polish Scouting and Guiding Association, an organization seeking to regain independence by Poland.

World War I broke out when the Pilecki family stayed in the spa resort of Druskininkai for vacation. Unable to reach Vilna––as the city could have been occupied by German forces––or even more distant Olonets, Ludwika Pilecka took the children to her mother who at that time lived in Havrylkov in the Mogilev region. Witold sojourned back then in Orel at the home of Maria Winnicka, his mother’s eldest sister. Whilst there, he formed a scout unit. In the spring of 1918 he took part in what might have been his first combat operation––along with his friends, Witold broke into a Russian military warehouse, seizing army uniforms and other pieces of equipment.

In the summer of 1918, well aware of the Bolshevik threat, the Pilecki family left Havrylkov and headed toward German-occupied lands––first to Vilna and then to the Sukurcze estate, where Julian finally reunited with his loved ones. In Vilna Witold attended the Joachim Lelewel Gymnasium (secondary school), he also joined up with the underground Polish Scouting and Guiding Association (Związek Harcerstwa Polskiego, ZHP) and the Polish Military Organization.

In December 1918 he enlisted in the ZHP section of the Lithuanian and Belarusian Self-Defense Militia, a paramilitary formation aligned with the White movement under General Władysław Wejtko. When the German army began to withdraw from Vilna in 1918, on New Year’s Eve, Witold commanded the defense of the barricade at the Gate of Dawn. In 1919 he fought against Vilna communists who made efforts to support the Bolshevik army to seize the city. However, Vilna fell to Bolshevik forces and members of the Self-Defense Militia were forced to flee and then to lay down their arms by the German military––an act refused by Major Władysław Dąmbrowski and Captain Jerzy Dąmbrowski. Witold joined them; he took part in fighting with the Bolshevik and Ukrainian forces and in the battle to recapture Brest on the Bug. On the command of Captain Dąmbrowski Witold then rushed to Warsaw where he enrolled with the Kazimierz Kulwiec’s Gymnasium and joined the 40th Boy Scouts Team led by Stanisław Rudnicki. Having spent two months in Warsaw he came back to his parent branch transformed into the 13th Lancer Regiment. Pilecki served there until late September 1919 as in October he resumed education at the Joachim Lelewel Gymnasium in Vilna where he founded the 8th Vilna Boy Scouts Team. On July 11, 1920, he was assigned to the 1st Vilna Boy Scouts Company of the 201st Infantry Regiment and sent to defend Grodno. In the fighting he gave proof of his military commitment and incredible bravery by volunteering in a rescue operation to save his sleeping comrades, incidentally left by the Nemunas River, or by launching a successful campaign to attack Bolshevik forces firing machine guns at the Polish military. On August 12, 1920, Pilecki got involved in the 211th Uhlan Regiment under Major Dąmbrowski. Pilecki later took part in the battles near Płock––including the triumphant Battle of Góra, and those close to Białystok, Grodno, and Lida. He briefly served in the ongoing Polish-Lithuanian War as a member of the Żeligowski rebellion, a false flag operation that resulted in the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuania, formally annexed to Poland in 1922. Pilecki made a name for himself while patrolling the Rudniki Forest near the village of Ejszyszki where––alongside his comrades––he managed to capture a machine gun firing position, disarm, and take captive 80 Bolsheviks. He also took part in the fighting against the army of Kaunas Lithuania. In January 1921 Pilecki was transferred to reserve status to complete education and pass his school-leaving final exams in May that year. Back then he was fluent in Russian, German, and French; he also got briefly enlisted as an auditing student at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Stefan Batory University in Vilna he soon left due to financial problems.

At that time Pilecki was active at the National Security Union (Związek Bezpieczeństwa Kraju, ZBK) where he served until December 1923. He completed a non-commissioned officer’s training course and became a commandant-instructor of a local chapter of the Union in Nowe Święciany. While there, Pilecki worked as a clerk; one of his tasks was to oversee an operation to dismantle military hardware. Before March 1923 he had been a devoted member of the Polish scouting organization too.

In 1924 Pilecki moved to Vilna; he worked as a secretary of the Union of Farmers’ Associations of the Vilna region. On October 1, 1925, he began the job as a secretary of the prosecuting magistrate of the Second Judicial District in Vilna. On October 28, 1926, he would be promoted to second lieutenant, with seniority from July 1, 1925, and then assigned to the 26th Greater Poland Uhlan Regiment. Though Pilecki was not a graduate of an officer cadet school, he served on the front line for fourteen months between 1918 and 1921, a decisive factor behind his new military rank. He settled in the ancestral estate in Sukurcze, adjacent to the manor house in Borówka that belonged at that time to General Edward Rydz Śmigły, whom Pilecki got to know better during joint hunting in his forests. In the early 1930s he met his future wife, Maria Ostrowska from Ostrów Mazowiecka, a primary school teacher in the neighboring village of Krupa. They got married on April 7, 1931. In the summer of that year Pilecki did military training as a commander at infantry regiments in the Cavalry Training Centre in Grudziądz. Throughout the 1930s he completed training and drills at the 78th Infantry Regiment and 26th Greater Poland Uhlan Regiment in Baranavichy. His wife and he started a family in 1932 when their son Andrzej was born while a year later their daughter Zofia came into the world. At the same time Pilecki was in charge of the family estate in Sukurcze and was active in the local community; he was the chairman of a dairy, headed a volunteer fire brigade, and founded a farmer’s association. He also organized the Krakus Military Horsemen Training School in 1932. He was appointed to command the Military Training Squadron, which was placed under the Polish 19th Infantry Division in 1937. Possibly in the 1930s General Edward Rydz-Śmigły offered Pilecki a job in intelligence or counterintelligence services; he was active till the outbreak of World War II though little is known about his tasks. He ran a farm too––in September 1926, Pilecki inherited his family’s ancestral estate, Sukurcze, comprising over 100 hectares of land, of which 37.5 hectares was arable land while the remaining ones were meadows and forests. He also owned a manor, a yard, and farm buildings. Pilecki put all his efforts into repairing as well as modernizing his neighborhood. His wife worked as a primary school teacher in the village of Krupa.

Pilecki’s farm specialized in clover seed and dairy production, with its butter sold in stores throughout Vilna. Despite having a lot on his mind Pilecki also found time to paint; two of his paintings depicting St. Antony of Padua and Our Lady of Perpetual Help have survived in the parish church in Krupa. He also painted and made some drawings to decorate the manor they lived in. Pilecki took part in military drills too.

In the late summer of 1937 Pilecki was the commander-in-chief of the Lida Cavalry Squadron at the 19th Infantry Division. He also took part in drills under General Stefan Dąb-Biernacki. In consequence, he was a candidate for military promotion yet the outbreak of World War II thwarted these plans. In late August 1939 Pilecki mobilized as a cavalry platoon commander at the 19th Infantry Division; it consisted of five line platoon formations, a machine gun platoon, and a technical platoon. He served as deputy chief of the cavalry under Major Mieczysław Gawryłkiewicz and the chief of the Second Platoon. On the night of August 31, 1939, Pilecki and his division arrived close to Warsaw, from where they set off towards Tomaszów Mazowiecki in the morning of August 31, 1939. As the war broke out, the division was stationed near Łowicz, as part of the Polish Army Prusy under General Józef Kwaciszewski. On the night of September 5, 1939, the Germans destroyed Pilecki’s squadron during the heavy fighting at Wolborz. Alongside the dispersed soldiers, Pilecki arrived in Warsaw on the night of September 7, 1939, before heading on September 9 and 13 to Siedlce, Łuków, and Włodawa to enlist at the 41st Infantry Division under General Wacław Piekarski. Pilecki served there as divisional second-in-command of its cavalry detachment, under Major Jan Włodarkiewicz. The fate tied Pilecki close to Włodarkiewicz––like earlier to the two Dąmbrowski.

When the 41st Infantry Division suffered a fatal clash near Chełm in the second half of September 1939, Pilecki did not follow suit of his comrades and refuse to flee to Hungary. Yet he had no intention of laying down his arms, either. Until October 17, 1939, he took part in partisan warfare; his unit got disbanded near the village of Mordy. Initially Pilecki had a plan to return to Sukurucze; he eventually rested at his in-laws in Ostrów Mazowiecka, from where he made his way to Warsaw on November 1, 1939, living under the false identity of Tomasz Serafiński. Furthermore, Pilecki was active in creating the Secret Polish Army (Tajna Armia Polska, TAP), a national resistance movement based on Christian values and non-affiliated to any pre-war political wing. He coined the name of the organization headed by Major Jan Włodarkiewicz; he also became its chief of staff and later the chief inspector. Pilecki demonstrated a full commitment to the organization; he got it expanded to 20,000 members while its range covered cities and towns like Warsaw, Lublin, Cracow, Radom, and Siedlce. It also distributed clandestine press. Pilecki sought to merge the Secret Polish Army with the Home Army, an idea strongly rebuffed by Major Włodarkiewicz.

In 1939 and early 1940, some TAP members were arrested by the Germans. In response to these, in August 1940, Włodarkiewicz called a meeting, suggesting that a TAP member infiltrate Auschwitz. Asked by his superior, Pilecki volunteered to allow himself to be captured by the occupying Germans to smuggle himself into the Auschwitz concentration camp to draw up reports detailing Nazi atrocities at the camp and establish an underground resistance movement. Although initially hesitant, on 19 September 1940 he deliberately went out during a Warsaw street roundup in Żoliborz and was caught by the Germans. He had a false identity card in the name of Tomasz Serafiński. Pilecki was then sent to Auschwitz and was assigned inmate number 4859. He would be promoted to the rank of lieutenant on November 11, 1941, marking the anniversary of Poland’s regaining independence, the value he cherished so much. When at Auschwitz, Pilecki organized an underground Military Organization (Związek Organizacji Wojskowej, ZOW). In October 1940––with a little help from a former Auschwitz inmate––Pilecki fed his first intelligence up to General Stefan Rowecki (alias “Grot”), the commander-in-chief of the Home Army, and then in March 1941 to the Polish chain of command to London. From these snatches, they learned about the murderous labor inside the camp, inhuman punishment, and starvation. As an inmate Pilecki constructed a resistance network both discreetly and thoughtfully; at first, the ring did not include senior officers imprisoned under their names as they remained under the watchful eye of camp authorities and could have been exposed eventually. At first, vigilant not to arouse any suspicion, Pilecki did not seize an opportunity to write letters; later he wrote just a few of them. Inside the camp, he helped fellow inmates, asking camp authorities for better working conditions, extra portions of soup for the exhausted, food allotments, or to allow them to work indoors. In the fall of 1941 Pilecki asked Lieutenant Colonel Kazimierz Heilman-Rawicz, a member of the Union of Armed Struggle–Home Army (Związek Walki Zbrojnej-Armia Krajowa, ZWZ-AK), to command the resistance network. The military underground organization in Auschwitz soon embraced other nationals, too, for instance the Czech people. Pilecki made efforts to pass information through the former inmates to the headquarters of the Home Army in Warsaw. Their ultimate goal, he said, was to organize an uprising upon a Home Army order. He was hopeful that the allied countries would help Poland by dropping weapons and ammunition.

Yet senior officials at the Union of Armed Struggle–Home Army felt reluctant to this solution. However, this was not about German SS officers at Auschwitz and the support they could have from other military forces in nearby towns, turning the whole conspiracy into a failure. Instead, Home Army officers wondered how to manage a considerable number of released inmates and relocate them safely; also, they were fearful of Nazi revenge on their families and the Polish nation as a whole. Yet they did not exclude a possibility to take steps if conditions were adequate to start an uprising––for instance if Nazi officers sought to slaughter prisoners. The plan to liberate the camp later got approval from General Tadeusz Komorowski “Bór”. After Lieutenant Colonel Kazimierz Heilman-Rawicz was deported to the Mauthausen camp on July 7, 1942, Pilecki suggested that Lieutenant Colonel Julian Gilewicz take the lead in the Military Organization.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

Inside the camp Witold Pilecki was given different jobs yet everywhere he worked he was trying to promote the Military Organization––even in a prison hospital where he stayed in 1942 after contracting typhus. In addition to founding a clandestine military ring, Pilecki made efforts to bridge gaps between inmates showing distinct political viewpoints. Throughout March and April 1943, a total of 7,000 people were deported into Germany; the goal was to loosen ties and smash the resistance network. Witold Pilecki avoided being sent into Germany––first, as he faked an illness, and then thanks to an SS officer, who submitted a paper saying Pilecki was assigned to work in the parcel department. Pilecki drafted his report, with its purpose that may have been to get the Home Army command’s permission for the Military Organization to stage an uprising to liberate the camp; however, no such response came from the Home Army. On the night of 26–27 April 1943, after 947 days inside the camp, Pilecki alongside his two comrades––Jan Redzej and Edward Ciesielski––broke out of the camp. Although Pilecki had earlier had a plan to make an escape, he stayed to further expand the resistance network; also, he feared that Nazi officers would practice the rule of collective responsibility by killing other inmates, a procedure they relinquished sometime after. When making his way to Warsaw, Pilecki was shot by a German patrol they encountered incidentally in the Niepołomice Forest. Pilecki and his companions made a short stop also in Bochnia where he came into contact with a local chapter of the Home Army. As luck would have it, one of its leaders was the real Tomasz Serafiński (known under his codename “Lisola”), who lived in Wiśnicz, and whose identity Pilecki took while volunteering for Auschwitz. Then he got in contact with the Home Army command; he refused to go to Warsaw as he devised a plan to liberate inmates in a neighboring concentration camp. Pilecki eventually failed to forge closer ties with the Home Army command in Cracow; in consequence, he left for Warsaw on August 23, 1943, where he found a job in Section 998 of the Second Division of the Home Army Command. Later he requested a transfer to the Second Intelligence Department at Kedyw, a unit that conducted active and passive sabotage, propaganda, and armed operations against German forces. While at Kedyw, Pilecki took the nickname “Kameleon” (Cameleon). It is where he got the job of a deputy commander-in-chief. He also managed to come into contact with Lieutenant Colonel Jan Mazurkiewicz “Sęp,” whom he reported the situation in Auschwitz and who directed Pilecki to Major Karol Jabłoński “Zygmunt,” to whom he submitted the plan of an uprising inside the camp. He drew up a report on the military underground organization at Auschwitz. He also distributed Home Army financial aid to the families of Auschwitz and Majdanek inmates. On February 23, 1944, Witold Pilecki was promoted to captain with seniority from November 11, 1943.

He drafted up lists of volksdeutsche and other traitors sentenced to death. In the spring of 1944, then Colonel Emil August Fieldorf “Nil” assigned Pilecki to create a secret anti-communist organization, NIE, a double-conspired civilian and military resistance organization within the Home Army, tasked with replacing it once the Germans retreated from Poland and the Red Army entered into the country. Its purpose was to devise combat operations.

As an uprising broke out in Warsaw, Witold Pilecki did in fact disrespect an order from NIE by actively engaging in combat and serving under Major Leon Nowakowski “Lig”, a member of the National Armed Forces. The Chrobry II Battalion consisted of volunteers who fought in Warsaw downtown. On August 3, 1944, Pilecki took part in what appeared a successful assault on the Railway Post Office that spanned over railway tracks of the Main Railway Station. Later they captured the buildings of the Tourist House and the Military Geographical Institute. He took part in the fighting close to the streets: Pańska, Żelazna, Nowogrodzka, and Koszykowa, Starynkiewicza Square, and Jerozolimskie Avenue. Pilecki displayed outstanding heroism and bravery both in combat and towards his army comrades by taking the dead or the wounded out of the battlefield. Pilecki volunteered for service with the Warszawianka Company, a part of Kedyw’s Chrobry II Battalion, located in the Railworkers’ Union Building after retreating the Military Geographical Institute–Tax Chamber. It was tasked with shielding a viaduct from the side of Plac Starynkiewicza and railway tracks towards the Main Railway Station. In late September 1944 the Second Company of the First Battalion of Chrobry II was incorporated into the Second Battalion to the premises at Towarowa Street. Pilecki was assigned to rebuild its structures, a task he accomplished in just two days. They took part in fighting near the streets: Towarowa, Miedziana, and Pańska.

On October 8, 1944, Pilecki was taken prisoner and spent the rest of the war in captivity, first in the town of Lansdorf in Silesia and then in a prisoner of war camp in Murnau. The camp was liberated by General George Patton’s 3rd Army on April 29, 1945. On May 9, 1945, Pilecki met with General Tadeusz Pełczyński while two days later he was received by Colonel Kazimierz Iranek-Osmecki. His ambition was to carry on the struggle inside the country. He made his way to Italy where he became an officer of the Polish Second Corps led by General Władysław Anders. In August that year, he was reassigned to the Second Division of the Polish Second Corps under Lieutenant Colonel Stanisław Kijak, to whom he outlined a plan to set up an intelligence service to gather social and economic intelligence within the NIE organization. He was devoted to drafting up both his memoirs and a secret report on the resistance movement inside the Auschwitz camp. In September 1945, he spoke with General Władysław Anders and then in October 1945–– to General Tadeusz Pełczyński. Eventually, he traveled to Poland using the pseudonym Roman Jezierski––during the Warsaw Uprising and after, when taken captive, Pilecki held a German kennkarte, the basic identity document in use inside Germany and occupied territories. He arrived in Warsaw on December 8, 1945, where he founded an organization whose members were his fellows from Auschwitz, the Secret Polish Army, and the Home Army. Pilecki gathered intelligence to hand it to the Polish Second Corps yet he had no intention of fighting. Nonetheless, he was ordered to leave Poland and return to Italy; he refused, arguing he was unable to find a substitute for his undercover work. Pilecki put all his efforts into reestablishing contact with his former comrades. He also asked his wife and children to flee the country. He took an order from General Władysław Anders, trying to pass this instruction to some existing partisan units to disband and refrain from any sabotage. Pilecki smuggled out brief reports and photos to Italy; they contained some information from Captain Wacław Alchimowicz, a former member of the National Radical Camp (Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny, ONR) and an employee of the Ministry of Public Security, who reported on the criminal activity of the communist police. Other reports concerned foreign trade, schooling, and scouting. General Kazimierz Wiśniewski, the chief of staff of the Second Corps, greenlighted Pilecki to go ahead with his intelligence activity inside the country by gathering information on former Second Corps soldiers who suffered persecution and decided to return to Poland and plan transit routes westwards.

He was arrested on May 8, 1947, and thrown in a Mokotów jail. While interrogated, Pilecki sought to claim full responsibility for what did the anti-Communist underground movement. Pilecki’s interrogation was personally supervised by Józef Różański, who headed the Investigative Bureau at the Ministry of Public Security. The captain was accused of spying. Pilecki yet refused charges from Różański who claimed Pilecki staged a plot to kill senior police officers. In prison he was tortured barbarously: his nails were torn off, his legs were crushed, his testicles were crushed, he was stuffed on a leg of a chair. His Auschwitz accounts were not included in the case file; it is worth adding that Pilecki’s testimony is both a deeply moving and shocking read.

Pilecki stood an unfair show trial on March 3, 1948. The captain pleaded not guilty to spying and staging a plot to kill key figures in the Polish police. Neither did he confirm he had reaped some benefits from allegedly working as a foreign spy. Yet Pilecki owned up to carrying illegal firearms, saying it was hidden at the time of the Warsaw Uprising. He claimed responsibility for not having registered as a military upon his arrival in the country, which was a compulsory procedure back then, and using false identity papers as Roman Jezierski. The trial was a sham; Pilecki was not permitted to testify, nor were there any defending witnesses.

On May 15, 1948, Pilecki was sentenced to death, deprived of public and civil rights, while his property was forfeited to the state treasury. General Władysław Anders sought to help Pilecki by publishing his Auschwitz memoirs to inform the outside world that a hero was convicted; yet he saw nothing but indifference. Pilecki’s family and Auschwitz survivors tried to help him by pleading for help from Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz, a former Auschwitz inmate. These pleas for pardon written––also by Pilecki himself––both to him and President Bolesław Bierut were futile.

Witold Pilecki––a veteran of the two world wars, and the Polish-Soviet War, awarded with Poland’s highest honors, Auschwitz volunteers, founder of an underground resistance organization in the camp, Warsaw Uprising veteran, prisoner of war camp in Lansdorf and Murnau, Home Army officer, Polish Second Corps officer in Italy, one of the most venerated figures of World War II and in general––was shot in the back of the head by communists on May 25, 1948, at 9:30 pm.

Now Witold Pilecki is and should be a role model for sacrifice and love to the motherland. On October 1, 1990, Pilecki was finally exonerated posthumously and distinguished for his actions during World War II. In 1995, he received posthumously the Order of Polonia Restituta and in 2006 he was awarded the Order of the White Eagle, the highest Polish decoration. On September 5, 2013, Pilecki was posthumously promoted to the rank of colonel of the Polish Army.

NEWSLETTER

Author: Rafał Zgorzelski, PhD

A historian, publicist and manager. PhD in humanities in the field of history – a graduate of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. He gained professional experience in the regulated sectors. His research interests focus on modern political thought and contemporary geopolitical systems. Promoter of economic patriotism.

_________________________________

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.