THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 18 May 2020

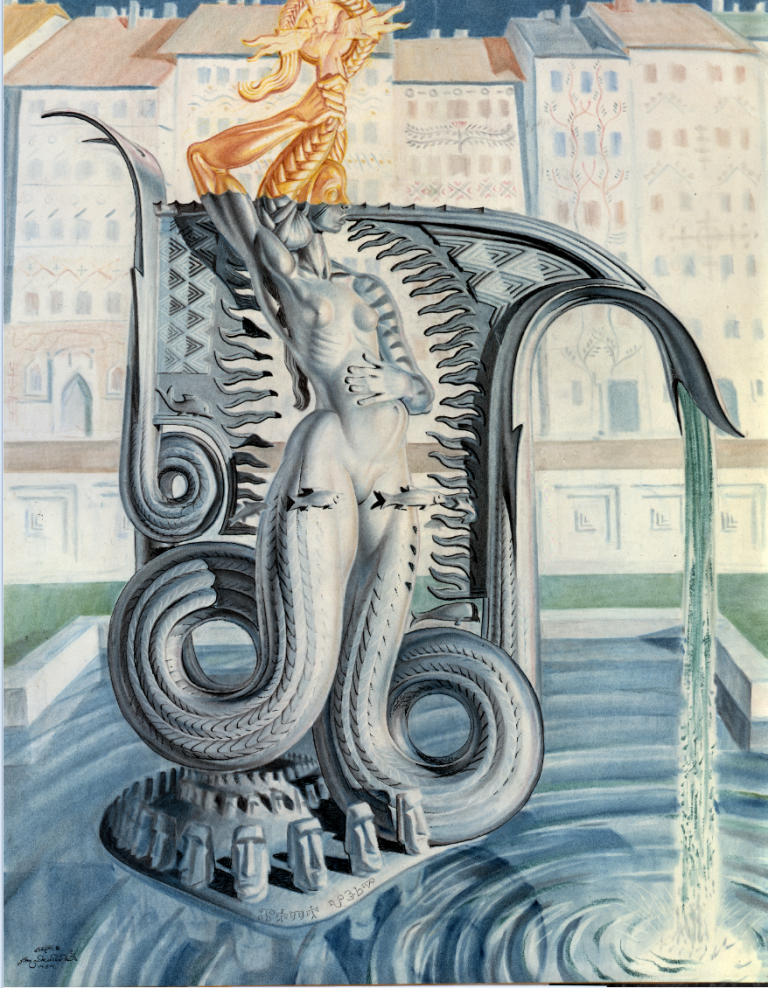

Stanislav Szukalski: The Human Riddle

A plethora of creatives from Eastern and Central Europe electrified the arts world in the first half of the 20th century. In a part of the globe where the legacy of empires was profound and where the social order would upend itself repeatedly until the onset of the Cold War, mutiny was in the air. Conventions were abandoned, while innovative new perspectives and techniques caught the eye of a new audience. Previously shunned as a backwater of Europe, critics began to take notice. While perhaps not given the same attention as artisans from certain other countries, Polish visual artists nonetheless found themselves in a better position to highlight their artistic achievements than they had in decades.

With a history of powerful forces pushing Poles to leave their native lands, it should come as little surprise that sons and daughters of Poland would weave themselves into the art scenes of other countries. Kazimir Malevich, Mela Muter, and Balthus are all noted painters whose Polish origin is often overlooked or absent in the discussion of their art. The same can not be said of Stanislav Szukalski, a dynamic figure full of passion and fire whose work exudes its own unique take on Polish history and Slavic folklore.

The aim of this piece is not to serve as an exhaustive history on Stanislav Szukalski, of which there are several excellent books in both English and Polish, as well as a recently released documentary film “Struggle: The Life and Lost Art of Szukalski” on Netflix. Instead, it is to look at certain episodes in the early life of the artist and examine how they subsequently affected Stanislav as well as his art.

In some ways, Szukalski’s biography seems beyond belief. A regular at the infamous Dil Pickle Club during the Chicago Renaissance, Stanislav would become embroiled in one of the largest art scandals of interwar Poland. The artist’s earthly path intersected with the likes of some of the brightest minds in Poland and the United States, such as Hollywood scriptwriter Ben Hecht, painter Jacek Malczewski, and actor Leonardo Di Caprio. Sure of his own talents, Szukalski created prodigious amounts of work, only to see much of it destroyed during World War II. Yet despite being an inspired creator, he was his own worst enemy. Szukalski’s verbal attacks on others in the art world ultimately denied him what he craved for most; an admiring audience.

A World In Need of Revolution

Szukalski was born in the town of Warta in 1893. A small Polish municipality dating back to the 13th century, the artist came of age when his birthplace had been a part of the Russian Empire for decades. Later in life, Szukalski paid tribute to his hometown with one of his artistic aliases as “Stach z Warty”, which translates into English as Stan from Warta.

It is impossible to understand an artist and their creative work without first getting a clear idea of their psychology. In the case of Szukalski, we can see how the life of the father he idolized influenced the future sculptor’s worldview. Stanislav’s father Dionizy was a blacksmith by profession, but he was also a revolutionary. Dionizy Szukalski was outraged by the injustices built into the European order that left Poles without a country after Napoleon’s defeat. This state of affairs drove Dionizy and many other political activists of his generation to be extremely determined to overthrow the imperial status quo of Europe at this time. It was an arrangement which Dionizy was driven to upset.

Being at odds with the establishment in territories under foreign occupation was not easy, and the family had to relocate again and again. Shortly before Szukalski’s birth, the family had fled for a short time to Brazil, where his sister Alfreda was born before returning to Russian occupied Poland. Financial struggles led Dionizy to leave his family in Warta for South Africa a year after Stanislav’s birth in 1893. After working there for a few years, the pull of the righteous fight against overwhelming odds led Szukalski’s father to take up arms in the Second Boer War against the British. Dionizy fought alongside the Boers until their defeat in 1902, after which he returned to his family and together they moved to Gidle, a village within the Russian Partition of Poland. They wouldn’t stay there for long however, as within a few years the family would cross the Atlantic Ocean and settle in Chicago, another hotbed of activism and discontent at this time.

A Real City

Although the young Stanislav Szukalski was reputed to have produced small sculptures in wood and stone for his peers in Gidle, it was in Chicago where the refining of his artistic inclinations began to take shape. Even his later schooling in Cracow’s prestigious Academy of Fine Arts was inspired by a comment from Polish sculptor Antoni Popiel to Szukalski while visiting the Windy City.

The city was simultaneously ripe with grit while in the midst of an artistic ferment, the beginning of an era when some regarded Chicago as the “cultural capital” of the United States. The Chicago School of Architecture and a wealth of literary talent are just two facets of a host of creativity coming out of the “City of Big Shoulders” at this time. Yet Chicago could also be a cruel place where people sometimes were treated little better than the cattle brought to slaughter in the city’s famous Union Stockyards. Rudyard Kipling poignantly alluded to this cruelty in his quote “I have struck a city – a real city – and they call it Chicago… I urgently desire never to see it again. It is inhabited by savages.”

It was in Chicago where Szukalski’s father died, the victim of an automobile accident. Stanislav came upon his father’s mangled body, and carried his corpse to the morgue. Some have theorized that the horribly distorted figures in some of Szukalski’s sculptures draw their inspiration from that grisly death scene.

The influence of his revolutionary father is perhaps best captured in during an exhibit by Szukalski at the Art Institute of Chicago, an event which went awry after the artist was criticized for calling out British Imperialism. Given that his father had fought against the British Empire as they tried to expand their reach over the African continent and likely touching a raw nerve since this was only a short time after Dionizy’s death, Szukalski flew into a rage. Instead of the art being taken down as the gallery demanded, Stanislav destroyed his work and had to be thrown out of the Chicago Art Institute.

Several motifs and philosophical quirks which Szukalski is known for can be traced back to his time in Chicago. The death of Stanislav’s father was quickly followed by the deterioration of his financial situation. Forced to work in the city’s meatpacking industry butchering livestock, Szukalski was surrounded by other Slavic and Baltic peoples who spoke different, yet similar languages to his native Polish, likely stirring Szukalski’s lifelong pursuit of searching for the common linguistic roots which later manifested in his philosophy of Zermatism and “rediscovery” of the human protolanguage.

Chicago ties together many of the threads which come together in Szukalski’s art. Is it a coincidence that Szukalski’s early works are so deeply imbued with Impressionism, and that the Art Institute of Chicago possesses one of the largest collections in that style outside of France? Or that the city, owing to the strength of its Polish community, imbued in him a strong attachment to the culture of his country of origin? Does Szukalski’s search for an indigenous American sculptural form not parallel the philosophy of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School of Architects Architecture? This is certainly a topic in need of further research.

Conclusion

Though his life may have straddled two continents, Szukalski’s artistic influences drew from all over the world. It’s a point which if he were still alive, the artist would likely deny. As Eva and Donat Kirch succinctly characterized Szukalski, “Like many other self-assertive avant-garde artists, he chose radical dogmatism to express his views and attract attention. His dreams, career, and life were to be realized by way of perpetual conflict with all those who who dared to disagree even on the smallest details of his art and views.”

When asked whether Szukalski’s art will finally gain the kind of mass reverence Stanislav sought during his life, Polish art historian Maciej Miezian answered by sharing a conversation he had with Szukalski’s friend Marian Konarski. Konarski, who had faced repression in his artistic career because of his associations with Szukalski, predicted that when Stanislav’s detractors eventually pass away, the next generation of fans would finally be able to popularize Szukalski’s works unimpeded. Recent events seem to suggest that may very well be the case.

Author: Daniel Pogorzelski

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.