THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 18 May 2020

Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

Russia-China: a limited liability military alliance

Over the last decades, Moscow and Beijing have strengthened their military relationship. This partnership, however, should not be described as a traditional alliance. China particularly avoids this kind of wording. After all, this cooperation is based not on collective visions, but rather on shared fears. It is hard to resist the impression that the only factor bringing the two countries closer is their common enemy.

What brings Russia and China together is mainly their rivalry with the United States. There is, however, a significant difference between the two in their perspective in this race. Russia is competing at political and military levels and China – primarily in economics and trade. This difference becomes, in the long run, a factor influencing Beijing’s cooperation with Moscow.

Of the two countries, Moscow is more interested in tightening their cooperation or even building a Sino-Russian alliance. A weakening Russia sees its partnership with Beijing as a solution against Washington’s global domination. Russia began to speak out about forming a partnership with Beijing shortly after it became clear that the reset policy towards the United States was coming to an end.

Over the last three decades, Russia and China have significantly developed their military cooperation (arms sales, joint military exercises, among others). The advanced weapons provided by Moscow have allowed China to strengthen its air defense and anti-ship defense. In particular, they have enhanced China’s capability to defend against the threat of foreign naval and air forces near its territory. Participation in joint exercises allows China to learn from Russian combat experiences gained in Ukraine or Syria.

Shortly before his death in 2017, Zbigniew Brzeziński, a Polish-American diplomat who served as a counselor to U.S. President Johnson and President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, said that “analyzing threats to American interest, the most dangerous scenario would be a grand coalition of China and Russia, united not by ideology, but by complementary grievances.”[1]. Beijing’s cooperation with Moscow has not yet reached that level. The armed forces of Russia and China are cooperating more and more intensively, but any integration of their military potentials is still out of the question. The Sino-Russian agreements in this area are, therefore, still far from the alliance treaties that the U.S. has with many countries in the world, including the ones in Asia, not to mention such an advanced military alliance as NATO.

Strategic partnership

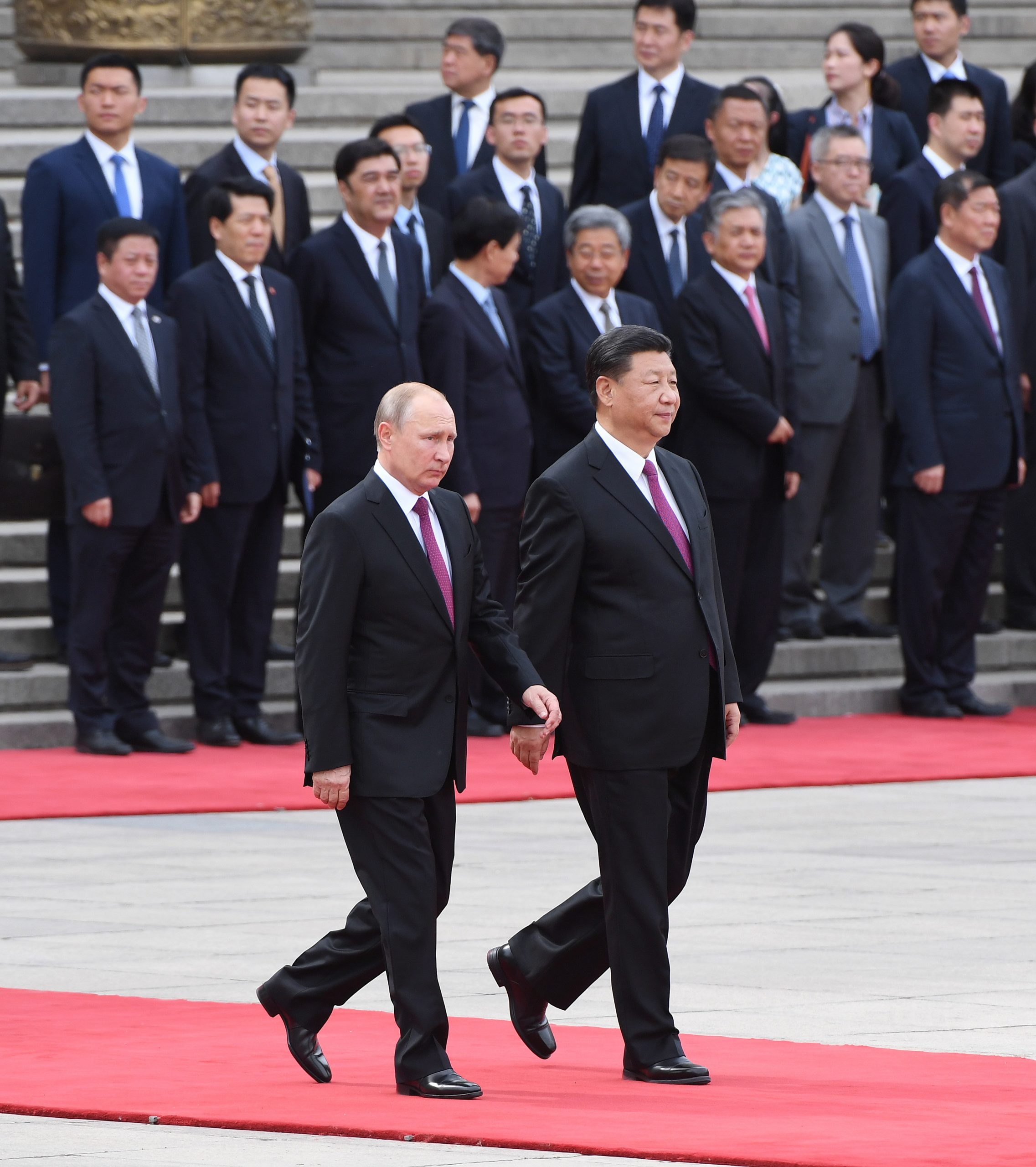

Nevertheless, today’s cooperation between the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China is the most intense since the two countries signed their Treaty of Friendship in 2001. Although Putin’s regime has never treated China as its enemy, Moscow’s long-lasting priority originating in the Yeltsin era was its cooperation with the West. The situation changed when Putin transformed its policy towards the West and made it confrontational, and when the United States became aware of the perilously growing potential of China – already far beyond exclusively economic issues. Although Putin made a turn towards Asia at the beginning of his third term of office, Russia has been actively promoting a “privileged strategic partnership” with China since 2014. However, the actual cooperation gained momentum after the two countries concluded a significant gas deal (‘Power of Siberia’ pipeline project). Moreover, Russia’s relationship with the West deteriorated after its aggression in Ukraine. China became Moscow’s top priority, and the former started to form its Eurasian strategy – with Russia being its crucial element. In addition to access to cheap energy supplies, close ties China’s western, weaker neighbor, offer Beijing an opportunity to develop its investments and political influence in the region, and, above all, to strengthen its position against the U.S.[2].

Already in November 2014, Russia openly suggested to Beijing to form a military alliance (with Russia’s Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and his deputy Anatoly Antonov speaking of the joint fight against terrorism and ‘color revolutions’). For a considerably long time, however, this idea did not hit the fertile ground in Beijing. China began to open up more to military cooperation with Russia only after the relationship of the former with the U.S. began to worsen after Donald Trump came to power. This also fits in with the increasingly forceful, global and expansive foreign policy pursued by China’s President Xi Jinping. For many years, this country’s military cooperation with Russia has boiled down to purchases of Russian armaments and, more recently, increasingly intensive joint military exercises symbolized by the participation of a large Chinese contingent in the strategic Russian military training activities – Vostok-2018.

In 2019, the cooperation between the two countries reached the next stage. At the end of July, the Russian A-50 airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft flew twice into South Korean airspace over Dokdo islands controlled by South Korea and additionally claimed by Japan. Seoul and Tokyo sent fighters against the intruders. South Korean pilots fired hundreds of warning shots at the Russian A-50. The most important thing in this incident was, however, something else – this reconnaissance aircraft accompanied the Chinese and Russian bombers. The next day, after the first-ever joint Sino-Russian airborne patrol, China’s Ministry of Defense published a document entitled “China’s National Defense in the New Era.” It reminds of China’s principle of not entering into military alliances with any country in the world, but also praises the development of military cooperation with Russia, which “enriches the strategic partnership between China and Russia in the new era by playing a significant role in maintaining global strategic stability.”

On the proving grounds

The greatest Sino-Russian rapprochement is visible in their joint military exercises – especially in their transition to joint strategic command and staff exercises and their readiness to use the armed forces together in military demonstrations in different regions of the world. Initially, the two countries took part in joint military exercises not on a bilateral basis, but on a larger scale. An example of such cooperation is the ‘Peace Mission,’ a project carried out by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) since 2005. As part of this initiative, these exercises aimed to improve cooperation in actions in Central Asia. The model of cooperation between Russia and China on water and land proving grounds began to change only in 2016 when exercises of the navy of the two countries were held near the Guangdong province. The scenario of the exercises consisted of, among others, landing, occupying, and defending the islands. It was the most massive naval operation of this kind in China and Russia so far. Less than a year later, in July 2017, the bilateral maritime exercise took place – for the first time in history – in the Baltic Sea.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

As mentioned, a joint action of the two countries that was of crucial importance for the cooperation was Vostok-2018, Russia’s training activities, to which their Chinese partner was invited. The Chinese contingent amounted to 3.5 thousand troops, plus armored vehicles, tanks, artillery, helicopters, and planes. Later on, China began to regularly take part in Russian exercises and war games, for example, in 2019 in Clear Sky 2019, Aviadarts 2019, or Tank Biathlon 2019. As part of another war game, Army 2019, the parties swapped their subdivisions – the Russian exercised in a Chinese proving ground, and the Chinese took part in various exercises in Russia[3]. In the autumn of 2019, Russia once again invited China to take part in its annual strategic exercise, which summarizes and tests the armed forces’ preparedness after the entire exercise season.

The agenda of Tsentr 2019 envisaged, among other things, large-scale offensive operations with air units and using Russian experience in Syria and Ukraine (rapid deployment of strike forces to occupy the territory before the opponent moves its reserves to this location). When practicing this type of operation, Russia had NATO in mind, while China was interested in the campaign against Taiwan – occupying the island in a massive landing operation before the U.S. comes to help. About 3,200 soldiers from China and over 20 Chinese aircraft took part in the training exercise with the use of heavy H-6k bombers capable of carrying atomic weapons. Sergey Shoygu and his Chinese counterpart, General Wei Fenghe, declared Tsentr 2019 a great success, demonstrating high levels of Sino-Russian cooperation and exchanged military experience[4].

During the past several years, both sides have engaged in many bilateral and multilateral exercises. Some of them were attended by Central Asian within the SCO, others, for example, by Iran – during a trilateral naval exercise in the Indian Ocean. The number and scale of exercises are increasing every year. What is valuable for the Chinese army, which has not fought in decades, is Russian experience in Syria on how to deploy brigade-sized forces that combine air and ground elements with special operations forces. China is also learning from Russia’s military experience, gaining knowledge on logistics of foreign operations and how to protect bases in foreign countries[5]. Joint military exercises are also intended to increase confidence between the two countries and inform about the other’s military intentions. This was the case during the Vostok-2018 exercise, when the Russian Eastern Military District, responsible for military planning for possible war scenarios with China, for the first time conducted its sizeable military training exercise with the participation of the Chinese army. However, it has not established a basis for joint major military operations between Russia and China. Even the SCO format lacks the mechanisms of integrated command, control, and support indispensable to conduct a large joint war operation. The military relations between Russia and China are still not as close as those between the U.S. and its allies.

Disagreements

In an assessment published in January 2019, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats said that “China and Russia are more aligned than at any point since the mid-1950s.”[6]. Nevertheless, compared to the diplomatic and economic aspects, the military aspect of the Sino-Russian partnership is still relatively weak in that it makes it impossible for Moscow and Beijing to forge an alliance. Furthermore, the participation of Chinese armed forces in the Vostok-2018 (and even more so Tsentr 2019) military training activities should not be overestimated. While Russia deployed several hundred thousand troops and about a thousand aircraft, China sent 3200 soldiers and six aircraft.

A classic full-fledged alliance between China and Russia is currently impossible because it would be based solely on their rivalry with the U.S. – perceived differently in Moscow and Beijing. Besides, there are many differences between the two countries – among others, the rivalry in the Arctic and the North Pacific, the two regions that Russia seeks to guard against competitors (China has growing ‘polar’ ambitions) and selling Russian weapons to Beijing’s biggest rival, India, and also to Vietnam.

Another field of silent competition between Russia and China is Central Asia, the fact of which can be observed within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Russia wants the SCO to remain purely military and limited to defense, while China would like to transform it into a more comprehensive body, a tool for developing economic influence in the post-Soviet area.

The end of the Russian-American INF treaty opens the way for the deployment of intermediate-range missiles near China also by its main continental neighbor. The missile arsenal of China has long been a factor taken into account by Russian strategists. The development of modernized and more precise Chinese intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) was one of the reasons why Russia began threatening to leave the INF as early as 2007.

Beijing does not endorse the annexation of Crimea by Russia and its factual annexation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, while Moscow does not provide formal diplomatic support for Chinese claims in the South China Sea and the East China Sea. Both Moscow and Beijing want to avoid being drawn into conflicts with third countries by the other side.

Can we refer to Russia and China’s relationship as to a military alliance? As some rumor says, in 1969, Soviet Chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin stopped over in the Beijing airport for talks with his Chinese counterpart, Zhou Enlai, when coming back from the funeral of Ho Chi Minh. When the host wanted to welcome the guest, Kosygin drew back, saying, “This is premature.”[7]

An alliance? Not necessarily

Only recently, Russia started using the word “ally” to refer to China. One of such first public uses was a comment of the Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov on the Chinese participation in the Russian strategic exercises Vostok-2018: “It is a sign of the expanded partnership between the two sides in all spheres.” In June 2019, the Russians described the agreements signed by Putin and Xi in Moscow as the opening of a ‘new era,’ also in the military cooperation of both countries. China did not publicly correct the statements made by the Russians; it probably made it clear ‘behind the scenes’ that it did not approve of such a message, which can be concluded from what Putin said a few days later. “We do not have any military alliance with China. We are strategic partners: we do not act against each other; we work for the benefit of ourselves and our partners, and we do not intend to swap or remove anything,” Putin said at The St. Petersburg International Economic Forum[8]. A similar situation occurred in the second half of the year when on October 3, 2019, Putin said that Russia was working with China to build a joint radar missile defense system and mentioned the “allied relationship” with Beijing. Nevertheless, already in December, during his annual press conference, he assured that the said radar system is purely defensive, and Russia is not planning to form a military alliance with China, even though it is helping the PRC to build a missile warning system.

China is careful when it comes to using the word “alliance” to describe its relationship with Russia. There is a difference between how Beijing sees its military cooperation with Russia and how Moscow does. The rapprochement of the two countries results from bad relations with the U.S. of both China and Russia, and it is, nevertheless, limited by concerns of both sides. Russia is not particularly keen to develop cooperation in certain areas where it has a clear technological advantage over China. Beijing, on the other hand, treats cooperation with Russia more as a tactical, temporary state intended to serve only its own interests. The statements made by Russia (with Putin at the forefront) mirror a new level of military partnership – a kind of “undeclared alliance.” Russia wants to develop military cooperation with China in specific areas: in the air and at sea – which is clearly directed against the U.S. At the same time, Moscow does not want to hurry with supporting China in modernizing its land forces – the element of military potential that could threaten Russia in the future[9].

The June 2019 “Joint Statement on Developing a Comprehensive Partnership of Strategic Coordination for a New Era,” states that in developing of their bilateral relations, Russia and China “refuse to forge an alliance, to confront and to act against third countries.” It also mentions a “strategic alliance” that does not, however, contain one crucial element of every alliance: the firm commitment to provide military assistance if one of the allies becomes a target. Although it is worth adding that the still valid Article 9 of the 2001 Sino-Russian Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation states: “When a situation arises in which one of the contracting parties deems that peace is being threatened and undermined or its security interests are involved, or when it is confronted with the threat of aggression, the contracting parties shall immediately hold contacts and consultations in order to eliminate such threats.”[10].

A missile rapprochement

The Sino-Russian defense partnership falls into several categories – arms sales, military exercises, meetings, declarations, and exchanges. Recently, there has been a particular strengthening of cooperation in the latter group – these exchanges have become more institutionalized and better integrated. Military leaders of both countries meet frequently and regularly in various bilateral and multilateral formats. They issue numerous joint statements on various security issues, including missile defense, the militarization of space, international terrorism, and regional issues, with the Korean conflict at the forefront[11].

A new stage in the military cooperation of both countries began in 2018, although already in 2017, a three-year roadmap for bilateral military cooperation was signed from Russia’s initiative. Beijing became more inclined to such cooperation only after the beginning of the trade war with the U.S. The development of contacts in the area of technology and emphasis on strategic armaments have become a characteristic feature of the current Sino-Russian cooperation in the military area. Moscow admitted that it helped China to set up a missile warning system, which is the most important and sensitive component of any country’s strategic nuclear power management system. However, it is not clear what elements of the early warning system were involved in Russian contribution – whether it was the ground part or the space part; the management and data processing system, or all these elements at once. What was known was only that Russia and China cooperate extensively in building missile and air defense systems in the domain of warfare (for example, regular joint exercises of anti-aircraft forces as part of “Aerospace Security” computer simulation).

NEWSLETTER

Nowadays, cooperation can be expected in terms of strategic missile defense, supersonic technologies, or construction of nuclear submarines. These are areas from which both sides can benefit without compromising their strategic security interests. If there were to be a crisis with China in the future, Russia would be most concerned about the strength of China’s land-based troops and the arsenal of medium and short-range missiles. Increasing the capabilities of the Chinese ocean fleet, building a strategic missile early warning system, building strategic missile defense, or increasing the number of intercontinental missiles does not pose a problem for Moscow. The coordination of strategic early warning systems for rocket attacks would be a major strengthening of the defense capabilities of both countries. Russia could count on Chinese radars, while China could count on Russian ones – of course, in the context of the threat of a nuclear strike by the U.S.

The Arctic and Arms

Since the threat of a potential impact of American intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) comes from the Arctic, it is China’s vulnerable northern flank in the context of this country’s nuclear safety. The key components of U.S. missile defense are located in Alaska. A report published in January 2018 by China’s State Council Information Office, titled “China’s Arctic Policy,” indicates three core priorities for China’s Arctic interests. One of them is the security (anquan) – the Arctic is of crucial importance for China’s nuclear deterrence. China wants military access into the Arctic to strengthen its strategic position vis-à-vis the U.S. The Chinese underwater fleet has six Type 094 ships, each of which can carry 12 intercontinental JL-2 ballistic missiles with a range of 8-9 thousand kilometers. Beijing is also working on more advanced Type 096 ships (which are to start being used between 2022 and 2023). It will be possible in each of them to arm it with 24 JL-3 missiles. Stationed in Arctic waters, the Chinese would significantly reduce the distance of their catapults from U.S. land targets. For example, the distance from the Chinese coastline near Shanghai to New York is 11,800 kilometers, whereas from the North Pole it is 3,400 kilometers – three times less[12]. In the annual Pentagon report on China’s military power published in May 2019, a section devoted to Beijing’s military interests in the Arctic appeared for the first time[13]. In August 2019, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg expressed concern about “China’s increased presence in the Arctic.”

If Chinese nuclear-armed submarines were able to access the Arctic basin undetected, the balance of power would change completely. The targets in the U.S. and Europe would immediately be within China’s reach. To reach this area, however, the PRC fleet must get through several chokepoints closely monitored by Japan, the U.S., and Russia: the straits that divide the Japanese archipelago; the Bering Strait; and the waters surrounding the Russian islands along the Northern Sea Route (Severnaya Zemlya – the Northern Land and New Siberian Islands)[14]. In May 2019, Russian analyst Alexander Shirokorad raised the possibility of Russia providing port support for Chinese submarines in the Arctic and proposed a joint Russia-China air and missile defense system for the Arctic[15]. Moscow may be ready to allow the Chinese fleet to enter these waters, linking this to Beijing’s involvement in the development of the Northern Sea Route (investments, loans, technologies).

Russia played an important role in modernizing China’s military equipment. What is more, it may also be interested in Chinese products, such as drones and ships. As far as arms exports are concerned, Moscow has taken advantage of the restriction on China’s access to Western products (sanctions introduced after the Tiananmen Square massacre). In the 1990s, Moscow sold a large number of Su-27 to Beijing and even granted a license on its production in China. However, China later broke the contract and used the acquired technological knowledge to build its own J-11 fighter, a near-copy of Su-27. Nevertheless, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China was Russia’s largest client between 1999 and 2006 (in 2005. China accounted for 60% of the volume of Russia’s exports of weapons)[16]. This was followed by a sharp decline in China’s share in Russian exports (in 2012, it accounted for only 8.7%). The arms trade between the two has been restored in recent years. In 2015, the two countries concluded a contract for the sale to China of the S-400 and Su-35air defense systems – one of the most advanced Russian weapons. It should be said, however, that Russia also sells them to other countries and that from 2013 to 2017, a Chinese rival, India, was the largest recipient of Russian weapons (with 35 percent of Russian arms exports going to this country, compared with 12 percent going to China)[17]. In June 2019, Moscow announced that it intends to sell the second batch of advanced Su-35 planes to China. Furthermore, it may also sell Su-57. In March 2019, information was published that China and Russia are already jointly building heavy-lift helicopters, a total of 200 units for 20 billion USD[18]. On January 27, 2020, Russia has concluded the delivery of the second S-400E regimental set.

What is on the paper?

Paradoxically, observing the restoration of the arms trade, joint exercises, and military patrols, shows how Sino-Russian cooperation is delayed in the context of documents and formal agreements. The Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation Between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation signed on July 16, 2001, does not include a defense clause in which both parties would undertake to provide military assistance in the event of aggression by a third country. The document allows defense cooperation but does not give a possibility for joint military action against a third country.

The Russian government approved the present agreement between the defense ministries of China and Russia on October 11, 1993. The relatively short and general document focuses on creating conditions for cooperation in the area of military technologies of the two countries. It mentions training of personnel, exchange of experience and information, mutual assistance in servicing weapons and military equipment, and joint scientific and historical military events.

The document did not provide for joint military exercises but mentioned inviting representatives of the other country to exercises as guests. The document did, nonetheless, leave room for other forms of cooperation by adding a provision that they are “subject to agreement between the parties.”[19]. As a result, by December 1 of each year, the two countries would sign a cooperation plan for the following year, detailing the steps for developing mutual cooperation. Sometimes additional agreements were signed, such as the 2007 agreement on the status of troops temporarily stationed on each other’s territory – which was made after regular joint exercises started to be organized in 2005. In 2017, a three-year roadmap was adopted, providing a legal basis for a wide range of forms of military cooperation between Russia and China. All already existing new military contacts, as well as plans for the next ones, will most certainly be included in a new military cooperation agreement, which will replace the already outdated 1993 deal. Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship will also soon expire – in 2021. It cannot be ruled out that the new document will include provisions concerning the joint defense of China and Russia. This may turn out to be the most accurate indication of the actual level of military cooperation between the two countries and, last but not least, of the intentions of their leaders for the future.

Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

[1] John S. Van Oudenaren, America’s Nightmare: The Sino-Russian Entente, The National Interest, 12.01.2019

[2] Warsaw Institute Special Report, Chinese-Russian Unequal Partnership, Warsaw Institute, 27.06.2019

[3] Marcin Gawęda, Rosyjsko-chińskie wojskowe „braterstwo”, Defence 24, 14.09.2019

[4] Pavel Felgenhauer, Russia Completes Massive Tsentr 2019 War Games With Enhanced Chinese Participation, Jamestown Foundation, 26.09.2019

[5] Richard Weitz, The Expanding China-Russia Defense Partnership, Hudson Institute, 13.05.2019

[6] Warsaw Institute Special Report, Chinese-Russian Unequal Partnership, Warsaw Institute, 27.06.2019

[7] Leon Aron, Are Russia and China Really Forming an Alliance?, Foreign Affairs, 04.04.2019

[8] RIA Novosti, Путин заявил, что Россия и Китай не создают военныхсоюзов, RIA Novosti, 07.06.2019

[9] Paul Goble, Russian-Chinese Military ‘Alliance’ Both More and Less Than It Appears, Jamestown Foundation, 22.10.2019

[10] Василий Кашин, Необъявленный союз. Как Россия и Китай выходятна новый уровень военного партнерства, Carnegie Moscow Centre, 18.10.2019

[11] Richard Weitz, The Expanding China-Russia Defense Partnership, Hudson Institute, 13.05.2019

[12] Sergey Sukhankin, Russian-Chinese Military Alliance in the Arctic: An (Im)Possible Prospect?, Jamestown Foundation, 31.05.2019

[13] Annual Report to Congress, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019, Office of the Secretary of Defense, 02.05.2019

[14] Anne-Marie Brady, Facing Up to China’s Military Interests in the Arctic, Jamestown Foundation, 10.12.2019

[15] Александр Широкорад, Борьба за Арктику нарастает, Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 17.05.2019

[16] Siemon T. Wezeman, China, Russia and the shifting landscape of arms sales, SIPRI, 05.07.2017

[17] Leon Aron, Are Russia and China Really Forming an Alliance?, Foreign Affairs, 04.04.2019

[18] Stephen Blank, Joint Bomber Patrol Over the Pacific: The Russo-Chinese Military Alliance in Action, Jamestown Foundation, 30.07.2019

[19] Vassily Kashin, Joint Russian-Chinese Air Patrol Signifies New Level of Cooperation, Carnegie Moscow Centre, 30.07.2019

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.