THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 05 May 2021

Author: Sławomir Moćkun

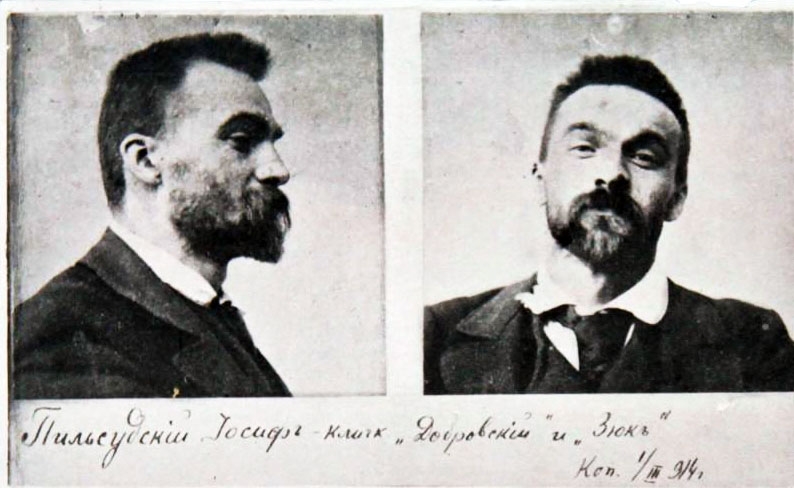

JÓZEF PIŁSUDSKI’S EXILE, IMPRISONMENT, MISSIONS AND PEREGRINATIONS ALL OVER THE WORLD

The following article chronologically presents the trips abroad taken by Józef Piłsudski. The considerations concern the period of the partitions and the Second Republic of Poland. As a statesman, the prime minister and co-creator of independent Poland, he was bestowed with the highest honour by the authorities of different countries. According to the memoirs written in the epoch, Piłsudski seemed to like traveling and visiting places of interest.

It is very simple to present on the map all the places that Józef Klemens Piłsudski visited during his lifespan as they basically come down to the entire northern hemisphere. All the expeditions that Pilsudski took on four continents, either voluntarily or involuntarily, enforced by the invaders, may serve as a discussion for the entire publication cycle. Pilsudski undoubtedly understood the world and its complexity, he valued its diversity, explored the secrets of nature, culture, and above all history, including the military aspects. At the same time, he shaped it courageously.

Pilsudski’s perception of the world was not related only to his interests and in-depth reading, but also to his own experiences and observations. Not only did the deportation, imprisonment, missions and peregrinations make up his legend, broaden his horizons, constitute a base for the first resistance and later state activities, and also serve health purposes, but, they fulfilled the Marshal’s curiosity of the world. Long expeditions, as well as the exile to Siberia, were used as the subject of numerous anecdotes. What Piłsudski was really interested in till the end of his life were foreign policy and defence issues. The Marshall often hosted foreign diplomats and politicians and was keen to be surrounded by people equally interested in the world, such as an adjutant, Capt. Miroslaw Lepecki or the secretary Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna. At the banks of the Thames, Neva or Seine, and even in distant Tokyo, he got acquainted with prominent political activists who in 1918, were in favour of the reemergence of the independent Republic of Poland on the European arena.

The journeys were one of Józef Piłsudski’s passions. Ziuk, started his travelling at the age of 7, after the fire of the manor in Zułów, and trav- elled almost to the end of his life. However, he saw himself firmly rooted in the independent Republic, never opting for the fate of a political emigrant. Visiting monuments and natural wonders, such as the Egyptian pyramids or Niagara Falls, he really felt at home in Pikieliszki or Sulejówek. In win- ter, visiting the world’s most popular resorts, during the summer holidays he preferred resting in Druskininki, Ciechocinek, Moszczanica, Zakopane, and Zaleszczyki.

Ziuk, who shared reading passion with his father, preferred books about ancient Greece and Rome, as well as travel, and as a child he played adven- tures of heroes created by Jules Verne. The curiosity of the world was con- firmed by the results of his matura exams, where he received the best grades in history and geography. When he was a child, until the manor in Zułów burnt down, governesses gave lessons of French and German. Ziuk’s parents made sure that on Christmas Eve daughters and sons could find books in French and German respectively under the Christmas tree. Piłsudski did not have any problems with the German language and his comprehension was so strong that he did not have to take the matura exam for the language. He absorbed German gradually, but started learning English only at the age of 20 during his stay in London and later, having a lot of spare time, in a cell of the X Pavilion of the Warsaw Citadel. It was not until the gymnasium that he unwillingly started learning Russian. These were times when Greek and Latin were taught at schools.

Young Józef Piłsudski got to know the western part of the Russian Empire very well, where intellectual, cultural, economic, military and political life were concentrated. Of course, he was also well-acquainted with ethnographic Lithuania, where he often spent holidays with his family (in the letters from Siberia he mentioned that he had never seen the Nemunas before), as well as with Belarus. During his medical studies in Kharkiv (1885-1886), he encountered the anti-tsar conspiracy as well as socialist ideas. The city, however, was too dominated by the “Russian soul”, so the rebellion ended with a six-day solitary confinement and, consequently, the decision to study in a more “European” and intellectually liberal Dorpat. He even considered learning outside the Russian empire. From Kharkiv, after a short stay in St. Petersburg, through Dorpat, Piłsudski returned to Vilnius in the spring[1].

SIBERIAN “UNIVERSITY”

On March 22, 1887, in Vilnius, instead of continuing studies, Józef Piłsudski was placed under arrest. Being suspected of participating in the anti-Rus- sian conspiracy he found himself in the cell of the St. Petersburg fortress on April 2. Three weeks later, he was convicted administratively for 5 years of hard labour, i.e. without indictment and evidence of complicity, for the attempt to assassinate the Tsar. Nineteen-year-old Ziuk soon set out on the route in the footsteps of the January insurgents he admired, first reach- ing the famous Butyrka prison under Moscow, and then through Nizhny Novgorod, Perm, Tyumen, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk he arrived in Irkutsk. The journey, which took over 4 months and was about 7 thousand kilometres by train, kibitka carriages, barges on the Volga, Kama, Irtysz and Ob, and the last stage taken on foot and on primitive carriages, provided Pilsudski with “new impressions and thoughts”. Despite the hardships of the journey, he wrote in a letter from Krasnoyarsk that “it’s an interesting country which is worth seeing”, paying attention to the amazing nature, unspoilt summer. It contrasted with the stale air of the overcrowded barge-prison, the severity of turmas “visited” on the way in Tyumen and Tomsk which were dirty, infested habitat of diseases, as well as spartan conditions of stage stations. Piłsudski was also accompanied by hunger, fatigue, dust, insects and con- stant torment, which was the brutality of Tsarist soldiers. The fact that he was the only Pole in the entire convoy, with no friends or old companions, further strengthened the isolation. His hostility towards everything that was Tsarist started to intensify. Piłsudski consistently refused to shake hands of Russian officials. He had a lot of time for meditation. “I am now living for the future; the future is all I have now” he wrote in autumn. “The present seems not to exist” he added, indicating that it takes only a negative face. In turn, the past “passed like a dream […] without giving the opportunity to develop all strength.” Already on his way to Siberia, Ziuk, “thrown into the abyss”, had no intention of falling apart, which was announced by the words “But to live means to learn”, sent in the letter[2].

In December 1887, he was eventually sent to the final place of exile, Kirensk, a small town located more than a thousand kilometres to the north surrounded by the Lena river, which could only be reached by sleighs after freezing at the temperature of several dozen degrees below zero. The exiles were the only intelligentsia in this settlement inhabited by approximately one thousand people. Serving the penalty for the Irkutsk rebellion was the most difficult moment, as staying in a poor wooden prison in a very low temperature, nearly cost Pilsudski his life. The last part of the sentence took place in the hospital, where he even held the duties of a writer[3]. Ziuk owed overcoming the difficulties and monotony of the exile to two peo- ple – Stanisław Lande, a January insurgent and a socialist activist, and his sister-in-law – Leonarda Lewandowska, who became Piłsudski’s first love. The harsh climate was partly compensated for by the rich nature. Piłsudski did not give in to general apathy and alcoholism, tried to stay in high spirits and also tempered his body[4].

The depressing climate of Kireńska meant that after two years, Ziuk wanted to “break out of this mud anywhere.” He unsuccessfully applied for a transfer to Sakhalin, where his brother Bronisław was sentenced to drudgery, as well as the possibility of serving the rest of his sentence in Vilnius. Eventually, he spent the last two years in a milder climate and better conditions in Tunka, located between Lake Baikal and Mongolia. “I really liked this place,” said Piłsudski. The beauty of the taiga was replaced by the monotonous, yet evoking the feeling of freedom, steppe with mountains to the south, and a typically Russian colony, this time with “a certain number of intelligent people” and the surroundings of the oriental culture of the Buryats. He got to know all kinds of Russians and views, from tsa- rist officials, to Trotskyists, anarchists and socialists. Above all, there was a large group of January insurgents, including one of its main organizers, Bronisław Szwarka, whose “individuality must have influenced the sensitive soul of the Marshal-to-be.” Szwarka, a person of enormous experience and penetrating mind, became a “professor” for Piłsudski, not only in terms of the Uprising of 1863. Ziuk also stayed in touch with him later on in Lviv. He attended his funeral, laying a wreath for “a friend and revolutionist”. The memories related to the Siberian Uprising of 1866 were also passed over Baikal, when a group of Polish exiles provoked a rebellion with plans reaching far beyond the desire to escape through China. Earlier, Colonel Piotr Wysocki, the initiator of the November Uprising, who was initially sent to the Irkutsk region, then served hard labour in one of the heaviest mines in Akatuj in the Zabajkal Country attempted to execute similar plans[5].

As an exile, he did not have any duties. In Tunka he taught children foreign languages. He would spend most of his time on long fishing and hunting expeditions (Piłsudski himself described them as “wasting gun-pow- der”), or skiing. He also ventured into the mountains, mostly alone, but sometimes together with Bronisław Szwarka and talked to the natives. The love for nature that flourished in Siberia stayed with Piłsudski till the end of his life. Nature became a kind of asylum, where surrounded by fields, forests or gardens, he could rest. Direct talks with the January insurgents, as well as the sight of numerous graves scattered throughout Siberia, triggered reflections about the causes of the fall of the uprising and plans for the new irredentism. He also mentioned the fortune-teller, who was to foretell him his future with the words “you will become a tsar.[6]”

The influence of the drudgery on the path later taken by Ziuk was described in his article written in 1903 “How I Have Become a Socialist” in which he claimed: “it was only here [in Siberia] where I could peacefully reflect on everything I had been through, and what I have become. First of all, I thoroughly got cured of the remnants of the Russian influences, and by getting to know many representatives of the Russian movement, as well as Russian literature and journalism, I have stopped overestimating the impor- tance and strength of the Russian Revolution. In this way, I have cleaned up my way to Western European influences”. Not only did Ziuk’s observations concern the socialist idea, but obviously the very construction of the Tsarist apparatus of terror, so visible in Siberia, “where, in the absence of culture, social factors occur in all their disgusting nakedness.” These observations strengthened the feeling already known from Vilnius – “I hated this Asian monster, covered with European veneer, even more”[7]. Russian literature, so popular among European socialist, did not appeal to Ziuk. The same concerned the Russians themselves, whose features, such as passiveness, shabbiness and anti-Semitism, were rather unappealing for Piłsudski. Very often in later times, he justified his opinion on the Russians with the vivid examples observed during the Siberian exile. There were also many exam- ples from “the other side”. Izzak Szkłowski, who returning with Piłsudski from the exile in Tunka recalled that during the stopover in Moscow, when they had a lot of time to visit the city, Ziuk ostentatiously refused to leave the station to manifest his contempt for the capital of Russia[8].

The period of exile to Siberia influenced the shape of not only the char- acter, but also coherent thinking about the direction of the development of the Polish socialist camp and its relation and expectations to “Russian comrades”. The article “Attitude to Russian revolutionaries” published in “Przedświt” (Pre-dawn), August 1893, was a declaration of the way, which was developed by a consistent political program whose foundations were formed during monotonous days in Siberia. The exile gave the future Com- mander a strong will and shaped his character. Siberia, against the will of the Tsarist court, became a university for young Ziuk where he found a master and lecturer – Bronisław Szwarce, specializations – the Uprising of 1863 and the Russian soul. Piłsudski understood who he wanted to become, and the legendary exile helped him to realise his plans. A passionate, romantic youngster changed into a disciplined realist with clearly defined goals and beliefs. Piłsudski returned from his exile to Vilnius at the beginning of July 1892, as a person with strong views and a well-formed character, his state of health, however, was very poor.

COMRADE VICTOR’S LONDON MISSIONS

The exile, also due to the contacts with the socialists staying there, was the best reference and certainly contributed to Ziuk’s fast career. Piłsudski straight away got involved in the work of the Central Workers’ Committee of the Polish Socialist Party, being a very active journalist. The conditions of the partitions made it necessary to transfer a large part of the activity, such as party and international congresses, and publishing activities, far from the Vistula. It was in Vienna, Paris, Brussels, Geneva, and London, where the Foreign Union of Polish Socialists (ZZPS) was located since 1893 and where during the congresses and meetings, the socialist movement shaped its strategies and with whom Piłsudski maintained constant contact. The presence of a strong Polish voice for the democratic and first of all independent Republic of Poland was even more significant as it opposed Róża Luksemburg, Julian Marchlewski and Adolf Warski-Warszawski, the leading figures fighting the idea of national sovereignty. Hence Piłsudski’s activity among socialists in Western Europe, mainly French, English and German, but also well-known to him Russian comrades and other nations enslaved by the Russian Tsar. Publishing was one of the most important fields of ZZPS activities. It included “Przedświt”, in which Pilsudski systematically published. In London, ZZPS, often at the personal request of “Wiktor”, issued Jewish press, Russian brochures and also Latvian or German publications. Józef Piłsudski used foreign contacts in conspiracy, sending correspondence, also to his immediate family, through contacts in Switzerland, Great Britain and even the United States[9].

Party duties, such as publishing and growing financial needs, made Piłsudski, operating under the pseudonym “Wiktor”, at the end of 1894, and in 1895, travel through the Russian Empire visiting major academic centres that focused on Polish intelligentsia (Saint Petersburg, Kiev, Dorpat, Riga). This activity probably included Moscow as well, where Ziuk’s brother, Jan studied. The “Robotnik” (The Worker) was accessible for his acquaintances from exile. Lidia Łojko was to receive it in Voronezh. Sources do not confirm whether Ziuk went to Tbilisi or Baku, where there was a large group of Poles, who could potentially financially support the PPS. In fact, tangible financial support came from the American Polonia, although only at a later stage of the fight[10]. In his first voyage to the west, “Wiktor” went to Switzerland at the end of 1894, where he participated in the congress of the Foreign Union of Polish Socialists. He came to London from Geneva for the first time. A few weeks spent there were devoted to organizational work, mainly publishing. On his way back to Vilnius, he visited Berlin and Tilsit.

In the spring of 1896, Piłsudski returned to London in order to discuss the current cooperation between the Central Workers’ Committee (CKR) and Foreign Union of Polish Socialists (ZZPS). The visit was extended to five months because Piłsudski decided to represent the CKR at the fourth congress of the Second Internationals. He stayed in the East End at Bolesław Jędrzejowski’s, who was his friend and an outstanding socialist at that time responsible for the publishing activity of ZZPS, and a few years later, managing the international activity of the PPS-Revolutionary Faction. Strolling in Victoria Park with Jędrzejowski’s children, Piłsudski ordered them to correct and improve his English. From the observations made at the time, he praised the English for taking care of physical development of children and a passion for sports, which became one of the important policies of the Marshal in the Second Republic of Poland. “An Englishman’s legs tend to move constantly, something is always pushed with his leg, he constantly pushes something,” Piłsudski jokingly concluded. He possibly also came across various ideas and movements that were popular at that time, such as suffragettes (Piłsudski as the Head of State gave women full electoral rights on November 28, 1918). He developed an interest for the local press, the course of the Boer War, including guerrillas that could be used in the possible irredentism in Poland. He focused on publishing activities including the preparation of extensive brochures, such as “May Souvenirs of 1896” and “peasant” daily, maintaining correspondence with the fight comrades scattered throughout Europe and the United States for the creation of an “independent Republic of Poland”. An extended stay in the capital of Albion, at least according to the correspondence with party colleagues, went against Piłsudski because he started feeling homesick. However, he quickly found the goal of the dissemination of his political program and the inclusion of Polish aspirations for independence in the resolution of the congress. The Polish delegation (Ignacy Daszyński, Aleksander Dębski, Antoni Jędrzejowski, Witold Jodko-Narkiewicz, Ignacy Mościcki, and Józef Piłsudski) prepared a text proposal, gaining the support from Liebknecht, Adler, Kautski, Plekhanov and Labriola. Piłsudski was particularly involved in allying with the German Social Democrats, speaking with Karl Liebknecht, who declared his support for Poland “going beyond ethnic boundaries”, “as wide and as far as possible to the east” and proposed a toast “Poland has not died yet”. Eventually, the expressive record[11] was simplified and replaced by a general short text admitting “every nationality has a full right to decide about its fate”, which was opposed by Rosa Luxemburg, Adolf Warszawski-Warski, as well as other German, French and Russian Social Democrats. This event irritated Piłsudski, and convinced him that it would be very difficult to gain support for the Polish cause from the international revolutionary community in the future.

In his article for the “Robotnik”, Piłsudski claimed that the tsarism was the main obstacle, a kind of “Chinese wall”, in close cooperation with comrades in the West. “Our first step must be the abolition of this wall, because only beyond it a more humane life begins” – he wrote in report on the congress published in the “Robotnik”[12]. Piłsudski was more optimistic in his search for war comrades among the nations enslaved by the Tsar, from Finland to the Caucasus. These convictions became even more permanent over the following years.

After returning to Krakow, he started working very hard. Due to its conspiratorial character, the details of Wiktor’s activity are not well-known. Maintaining remarkable correspondence with socialist outposts scattered over Europe and America, setting programs, publishing plans, strategies and possible alliances, he devoted a lot of time to raising funds. Because of that, in 1896 he went twice to St. Petersburg, providing the local communities with the course of the London congress. At the end of the year he went to “kacapia” (the Ruskie State) again, as he most often referred to Russia, to raise funds. “Wiktor” could still observe the situation in the Russian Empire at close quarters, appearing by the Neva in May 1897, to once again in autumn go to “the eastern goldmine” as he put it. In December Piłsudski represented the “country” at the ZZSP congress in Zurich, devoted largely to the publishing activity and personnel changes enforced by the “opposition”, which went against “Wiktor” and his idea. He tried to appease conflicts that had a negative impact on the conspiratorial work[13].

London was not only a publishing centre, but also a base that connected scattered companions at their work for the party. Piłsudski fought here against the idea of cooperation with tsarism, the United States of Russia. The purpose of the London base was fulfilled in 1898 by publishing the secret manifesto of General-Governor Alexander Imeretynski, in which the assumptions of the policy of seeming concessions made to the Poles were presented. This undertaking, with Pilsudski’s decisive personal commitment, who in July went with the stolen text to London through Zurich and Rapperswil, contributed to the resignation of the Tsar’s governor, weakening the position of the conciliators. Piłsudski claimed that the most Eastern European socialist outpost was located in Poland. Having established close contacts in the West, he was convinced that the only way for Polish socialism is its Western European version. Knowing Russia and the Russian socialists well, he could provide credible arguments supporting his view that regardless of its status, be tsarist or Bolshevik, Russia would always remain imperialist. In London, Piłsudski, whose authority was indisputable, settled the relations between the Central Workers’ Committee of the PPS and Centralization of ZZSP, keeping lively correspondence and carrying out publishing plans, including the centenary of Adam Mickiewicz’s birth. On August 2, 1898, he returned to Warsaw via Ostend and Dresden[14].

After his stay in St. Petersburg, in May 1899 Piłsudski left for London for the fourth time. The purpose of the two-week visit was organizational changes – submission of ZZSP to the PPS and takeover of the printing house. On his way back through the Rhineland and Westphalia, he intended to get to know the local Polish workers’ environment, and further through Dresden, he tried again unsuccessfully to visit Jerzy Haase, a promising leader of the PPS in the Prussian partition[15].

On the night of February 21-22, 1900 in Łódź, the “Robotnik” printing house was destroyed, and Józef Piłsudski was sent to the X Pavilion in the Warsaw Citadel. Foreign activity turned out to become very useful in coming up with an alibi after the arrest and trial (Piłsudski maintained that he had returned to Polish territory only recently, and from 1895 to 1899 lived in Paris, London, and in Switzerland or Austria). In turn, his admiration of the Siberian nature appealed to the doctor from Buryatia, Ivan Shabashnikov. Thanks to the opinion received from an influential psychiatrist, at the end of 1900 Piłsudski went for observation to the St. Nicholas hospital in St. Petersburg, which was part of the escape plan. Soon, through Tallinn and Riga, Polesie he arrived in Galicia. Getting out of the Russian prison thanks to simulated mental illness, was included in the so-called canon of famous escapes in the United States[16].

In June “Wiktor” restarted his activity and went to Kiev, where the “Robotnik” printing house was re-established. His plans to regain health in the Swiss Alps alongside Ignacy Mościcki[17], were changed to a stay in the Tatra Mountains. He also postponed the visit to London, where, as Leon Wasilewski recalled, “he had no intention of sitting there any longer: he wanted to continue his career, i.e. illegal work in the country.” Pilsudski, wanted by Tsarist Russia not only as a revolutionary, but also as a fugitive, did not intend to join the group of emigrant activists. Another stay in London (where he went through Poznań, and then through Germany and Belgium or the Netherlands) in the company of his wife was to serve two purposes – first was to rest, but also to discuss the directions and organization of the PPS fight (November 1901 – April 1902).

In December 1901, Piłsudski was to rest in the Southbourne-on-Sea seaside near Bornemouth, where Stanisław Wojciechowski worked in the printing house. In London, apart from the lecture for members of the PPS on the November Uprising and participation in the discussion convention organized by the Bund (in Russian), he did not engage in the monotonous life of a socialist colony, at least in comparison to the underground work in the country. It is worth mentioning that due to the restrictions in the country, it was one of the first speeches of “Wiktor” in front of a wider public. As Wasilewski recalls, the beginnings of the later excellent speaker were not very successful. The stay by the Thames was also important for defining a policy towards the tsarist occupant and the Russian people in the article “Autocratic hosts of Poland”, published in Geneva in the Russian “Svoboda”[18].

In mid-April 1902, “Wiktor” returned to the Polish land to support the “work”, and soon he went to Kiev. The stay in London gave birth to a new concept of the PPS organization. In this concept, the London centre lost its importance, and its activities, including publishing, were to be taken over by the Galician structures. The archives and the bookstore though were left in the capital of the United Kingdom. Soon, with significant Piłsudski’s contribution, in fact “London” moved to Galicia, which for objective reasons became the headquarters of further activities (Austrian authorities tolerated socialist activism, respected the right of asylum, and the dispute with Russia became more intense). “Wiktor” concluded that “foreign territory not connected with the country”, can no longer fulfil the role of the “party brain”, but could still function as its backbone. At the end of September, in Vienna, he discussed the financial issues of using PPS machines in London for printing papers for Russian socialists. In the winter of 1902/1903, the Piłsudski family went to Riga. During this period, Piłsudski often travelled “behind the enemy lines”, spending time in Minsk at the congress of the Central Workers’ Committee (December 1903), in Riga at the conference of socialist youth (January 1904), again in Minsk (February 1904) to go again through Riga to St. Petersburg (March 1904). By the Neva river, the Russo-Japanese war was the main subject[19].

[1] J. Piłsudski, Jak stałem się socjalistą (How I have become a Socialist), [in:] Pisma zbiorowe (Collective Works), Warsaw 1937, vol. 2, pp. 45-51; M. Lepecki, Józef Piłsudski na Syberii (Józef Piłsudski in Siberia), Warsaw 1936, pp 3-14; A. Garlicki, Józef Piłsudski 1867-1935, Cracow 2017, pp 21-33, W. Pobóg-Malinowski, Józef Piłsudski 1867-1914, London [no info], pp. 7-49, W. Suleja, Józef Piłsudski, Wrocław 2009, pp. 7-13.

[2] A. Garlicki, op. cit., pp. 36-39; M. Lepecki, Józef Piłsudski na Syberii… (Józef Piłsudski in Siberia), pp. 21-68; J. Piłsudski, Pisma… (Works…), vol. 3, pp. 65-74, Idem, Pisma (Works), Supplement, Warsaw 1992, pp. 13-15; W. Pobóg-Malinowski, Niedoszły zamach 13 marca 1887 roku i udział w nim Polaków (The Unfinished Assassination Attempt of 13 March 1887 and the Participation of Poles), “Niepodległość” (Independence), vol. X, Warsaw 1934, W. Suleja, op. cit., p. 15.

[3] Józef Piłsudski was also sentenced to a week of detention for breaking the ban on moving away from the perimeter of the place of exile. He went up the river by boat to visit a Polish friend who was also a deportee). He served the sentence in Tunka in good condi- tions in the house of the head of the local administration.

[4] M. Lepecki, Józef Piłsudski na Syberii… (Józef Piłsudski in Siberia…), pp. 71-78, 144-148, 152-154, Idem, Sybir bez przekleństw (Siberia without Cursing), Łomianki 2012, pp. 52-81.

[5] What could be important and relevant to Ziuk’s later activity is the fact that the insurgents could not rely on the Russian inmates, the local population, and also on some of the deportees-countrymen of noble origin who did not want to lose their privileged position and many amenities during their exile. J. Piłsudski, Pisma. Uzupełnienia… (Works. Supplement), pp. 16-17. M. Lepecki, Sybir bez przekleństw… (Siberia without Cursing, pp. 97-106. M. Lepecki, Sybir wspomnień (Memories of Siberia), Lviv 1937, pp. 167-182. In terms of Powstania Sybery- jskiego (Siberian Rebellion) go to H. Skok, Powstanie polskich zesłańców za Bajkałem w 1866 roku (The Uprising of the Polish Deportees in 1866), [in:] Przegląd Historyczny (Historical Review), no 54/2, 1966, pp. 244-269.

[6] A. Garlicki, op. cit., pp. 34-39; S. Juszczyński, Z pobytu w Tunce (From the Stay in Tunka), „Niepodległość” (Independence), vol. IV, Warsaw 1931, pp. 181-183; M. Lepecki, Pamiętnik adiutanta Marszałka Piłsudskiego (The Diary of Józef Piłsudski’s Adjutant), Warsaw 1987, pp. 191- 193; Idem, Od Sybiru do Belwederu (From Siberia to Belweder), Warsaw 1935, pp. 23-25; Idem, Józef Piłsudski…, pp. 21-113, 157-166; Idem, Sybir bez przekleństw (Siberia without Cursing), pp.137-144; A. Piłsudska, Wspomnienia (Memories), Warsaw 1989, pp. 94-95, 271; J. Piłsudski, Pisma zbiorowe. Uzupełnienia (Collective Works. Supplement), Warsaw 1992, pp. 17-78.

[7] J. Piłsudski, Pisma…(Works), vol. II, Warsaw 1937, pp. 52-53.

[8] A. Piłsudska, op. cit., p. 95; J. Piłsudski, Pisma… (Works…), vol. 3, pp. 65–74, L. Wasilewski, Piłsudski jakim Go znałem (Piłsudski as I knew him), Warsaw 2013, pp. 145-146.

[9] S. Cat-Mackiewicz, Klucz do Piłsudskiego (Key to Piłsudski), Cracow 2013, pp. 91-99.

[10] S. Cat-Mackiewicz, op., cit., pp. 116, 248-249; W. Jędrzejewicz, J. Cisek, Kalendarium życia Józefa Piłsudskiego 1867-1935 (The Calendar of Józef Piłsudski’s Life 1867-1935), vol. 1. Cracow 2006, p. 61; W. Suleja, op. cit., p. 31.

[11] In the wording “Considering that the subjugation of one nation by another one may lie in the interest of only capitalists and despots, but is equally destructive for the working people of both Polish and partitioning nationality; especially tsarist Russia, drawing its internal forces and external significance from the beaten and parted Poland, is a constant threat to the development of international workers life, Congress declares that Poland’s independence is a political demand, equally necessary for the international labour movement as well as for the proletariat itself.”

[12] J. Piłsudski, Pisma… (Works…), vol. 1, pp. 153-154; Idem, Pisma. Uzupełnienia (Works. Supplement), pp. 138-262; W. Jędrzejewicz, J. Cisek, op. cit., vol.1, pp. 86-88; A. Piłsudska, op. cit., pp. 96-97; W. Suleja, op. cit., pp. 32-33, „Niepodległość” (Independence), vol. XV, Warsaw 1937, pp. 418-432.

[13] L. Wasilewski, Józef Piłsudski jakim Go znałem (Józef Piłsudski as I knew Him), Warsaw 2013, pp. 115-120. W. Suleja, op. cit., p. 43; A. Piłsudska, op. cit., pp. 96, 124.

[14] A. Piłsudska, op. cit., pp. 176, 182; L. Wasilewski, op. cit., pp. 121-123; W. Jędrzejewicz, J. Cisek, op. cit., vol.1, pp. 112-118, W. Suleja, op. cit., p. 41.

[15] L. Wasilewski, op. cit., pp. 124-127

[16] W. Jędrzejewicz, J. Cisek, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 152-155; W. Suleja, op. cit., p. 50.

[17] Józef Piłsudski also really appreciated Gabriela Narutowicz’s activity in Switzerland and immediately started liking the person, even though they met only in 1919 in Warsaw. J. Piłsudski, Wspomnienie o Gabrjelu Narutowiczu (A Memoir of Gabriel Narutowicz), Warsaw 1923, pp. 7-8.

[18] J. Piłsudski, Pisma…(Works…), vol. 2, pp. 7- 17; L. Wasilewski, op. cit., p. 139; W. Suleja, op., cit., pp. 52-53.

[19] S. Cat-Mackiewicz, op. cit., pp. 121-122, W. Jędrzejewicz, J. Cisek, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 160-169, 188-198; W. Suleja, op. cit., pp. 50-54; L. Wasilewski, op. cit., pp. 138-150.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.