THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 4 December 2019 Author: Mike Bruszewski

Iraq survived the “Islamic State”

It is impossible to discuss the situation in the Middle East –– from social, economic, military, or, broadly speaking, geopolitical perspectives –– without taking into account the war with ISIL.

Regarded as second only to Syria in terms of being the critical battlefront against the so-called ‘Islamic State’ abbreviated as ISIL, ISIS, or IS, the shadow of ISIL had bedimmed Iraq, with jihadists having control of an dishearteningly large part of the country. This induced crises with regard to migration and a mass exodus of internally displaced persons (IDPs), and multifaceted crises, which include economic (war-related impoverishment of society), military (loss of territory to ISIL), and political, the latter of which pertaining to personnel reshuffles in Iraqi authorities and a change in the political moods across the country.

In March, the so-called Islamic State faced defeat in its final enclave in the Syrian town of al-Baghouz. Though ISIL insurgents had been subdued “in the field,” this yet did not put an end to inhumane practices of the terror group. The war against ISIL was not over, and what changed was nothing but its scale and dimension. Fighting had ceased while Syria’s Euphrates River Valley is now seeing what could be referred to as the process of ousting insurgents and ISIL marauders from the area, an operation which was conducted jointly by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Syrian Arab Army (SAA).

Iraq is de facto still where troops, law enforcement agents, and special service forces are carrying out an operation with a mission to detain further ISIL-linked terrorists, while ISIL itself is considered a real threat. Although Islamists no longer hold a grip on any part of Iraq’s territory, they still deem a menace after having gone underground. The so-called Islamic State, or a quasi-state genocidal creature proclaimed by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, bears full responsibility for war crimes. Though investigations are underway to estimate the scale of executions and persecutions, each subsequent month brings new revelations about the discovery of graves containing remains of ISIL victims, thus unveiling a horrifying truth about torture, killings, rape, and robberies ISIL insurgents committed. With the so-called Islamic State comes the nightmare of Yazidi women, or even girls, bought by jihadists at slave markets and treated as property.

While writing the report from a makeshift camp for displaced refugees near Dohuk, Iraq, I recall an account given by a Yazidi woman who managed to buy herself out of Islamist captivity. She was physically abused, and shortly before being freed from captivity, jihadi militants knocked her teeth out with a Kalashnikov rifle butt. I was in disbelieve as I was told how young this woman was as she looked elderly. Though she survived, al-Baghdadi’s thugs deprived the woman of her health and youth, and she ultimately found herself in a makeshift refugee camp, living in poor conditions. Though far from fusillades and rapes, she has taken up yet another struggle, fighting to survive every single day, albeit in the shelter for displaced refugees. There are thousands of accounts like hers.

What has come as an aftermath of the jihadist incursion is yet another ethno-religious turmoil which has yet to be resolved properly. This is also illustrated by the Christian community that had dwindled from around 1.5 million in the early 2000s to just 200,000. Added to this are the Kurdish aspirations for independence, the Sunni-Shia conflict –– that had grown exponentially also prior to the ISIL incursion –– and even the case of the Yazidi minority. Suffice it to recollect that northern Iraq, which served as the main theatre of war against the so-called Islamic State, is but a multi-ethnic and multireligious region inhabited by the mainly-Christian Assyrians, Yazidis, Turkmen, Arabs, and Kurds. An insightful look into ISIL activities shows that the group’s militant jihadis in the past tended to target similar melting pots due to their vulnerability to conflict. Iraq and the war against the so-called Islamic State saw both the involvement of a U.S.-led international coalition and the Iranian military intervention. Baghdad surely saw the war against ISIL as a test.

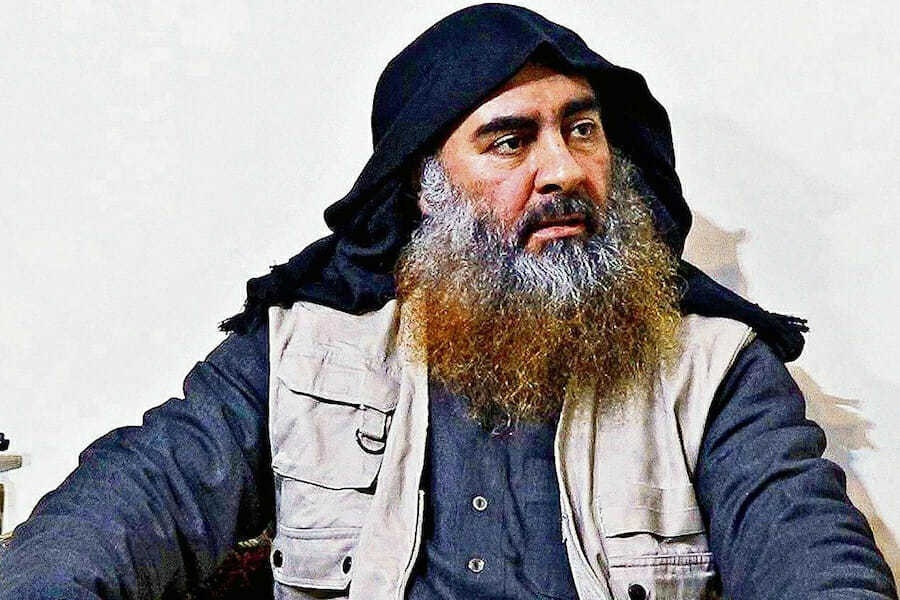

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, a self-proclaimed caliph

From the earlier stages, al-Baghdadi’s jihadi militants targeted Iraq to carry out their rogue activities. ISIL incubated out of a terrorist group known by its acronym of ISI –– the Islamic State of Iraq. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi for many years remained elusive. In June 2014, in Mosul, he announced the establishment of a self-proclaimed caliphate. Dubbed one of the world’s master criminals of the 21st century, al-Baghdadi has emerged as an object of analysis, with his biography being under scrutiny in search of further details. Al-Baghdadi personally made sure that the world knew as little about him as possible, avoiding public appearances, photographs, or video footage. He features in few materials, alongside the said 2014 “proclamation” of the “caliphate” in Mosul while in the latest video showing al-Baghdadi, the so-called Islamic State claimed responsibility for Sri Lanka’s bombings on April 21, and sought to deny rumors on his alleged death. Yet it is dubious whether the man with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s appearance was actually him.

Even after confirming reports on al-Baghdadi’s death in a U.S. raid on his compound in Syria’s Idlib province, experts are still pondering who the world’s top terrorist really was. What is known about Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi? Not incidentally, his moniker makes a reference to Iraq’s capital city of Baghdad. This is where he pursued a doctorate at the local university and served as an imam before branding himself a self-styled caliph. He is said to have harnessed radical Islam back when Saddam Hussein was in power. Interestingly, al-Baghdadi was reported to apply for the post of a state official in the time of the ancient regime, which means that his family nurtured friendly ties with the then ruling Baath Party of Saddam Hussein. As it later found out, among ISIL jihadi leaders were those identified as former senior officers in Hussein’s army.

It is unknown when exactly al-Baghdadi became affiliated with an Islamic terror group. At the time of the U.S. military intervention during the Second Gulf War (2003), he is believed to have preached at a mosque in the city of Samarra, Iraq. While establishing contacts with terrorists, he was arrested by chance, but a subsequent amnesty and his release could indicate that either al-Baghdadi did not hold a prominent position in the terrorist hierarchy or this fact simply escaped notice. When held in a detention center at Camp Bucca in southern Iraq in 2005–2009, al-Baghdadi was thought to have come into contact with other jihadi insurgents. He was to a great extent influenced by the extraordinary cruelty of his mentor, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq, notorious for slaughtering Shias and Christians. A more in-depth insight into al-Baghdadi’s biography of before then is challenging, and other terrorists went by a similar nom de guerre, as exemplified by that acquired by Abu Bakr’s immediate predecessor as the head of ISI, Abu Omar or Abu Hamza al-Baghdadi, killed in 2010. The self-styled caliph might have met al-Zarqawi as early as in the 1990s in Afghanistan, other sources reported. This would mean that he stepped onto the path to jihadism much earlier than previously thought.

Let’s go back to 2010. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi served as the “emir” of Rawa, a town in Anbar province, the region I refer to in the further part of the this written piece. Located in western Iraq close to the Syrian borderland, the province is dominated by Arab-Sunni elements and inhabited by tribes torn between the terror group and U.S. troops deployed to the area to fight against jihadi insurgents. Back then, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi gained notoriety for his ruthless efforts to kill opponents and enforce brutal Sharia law. The choice of the area they were active at the time was not incidental, showing al-Baghdadi’s endeavors to target regions hit by smoldering conflicts and earn the loyalty of local populations, the latter seen as a top priority. Then, 2011 saw the outbreak of a civil war in Syria.

Syria – a base for Iraqi offensive operations

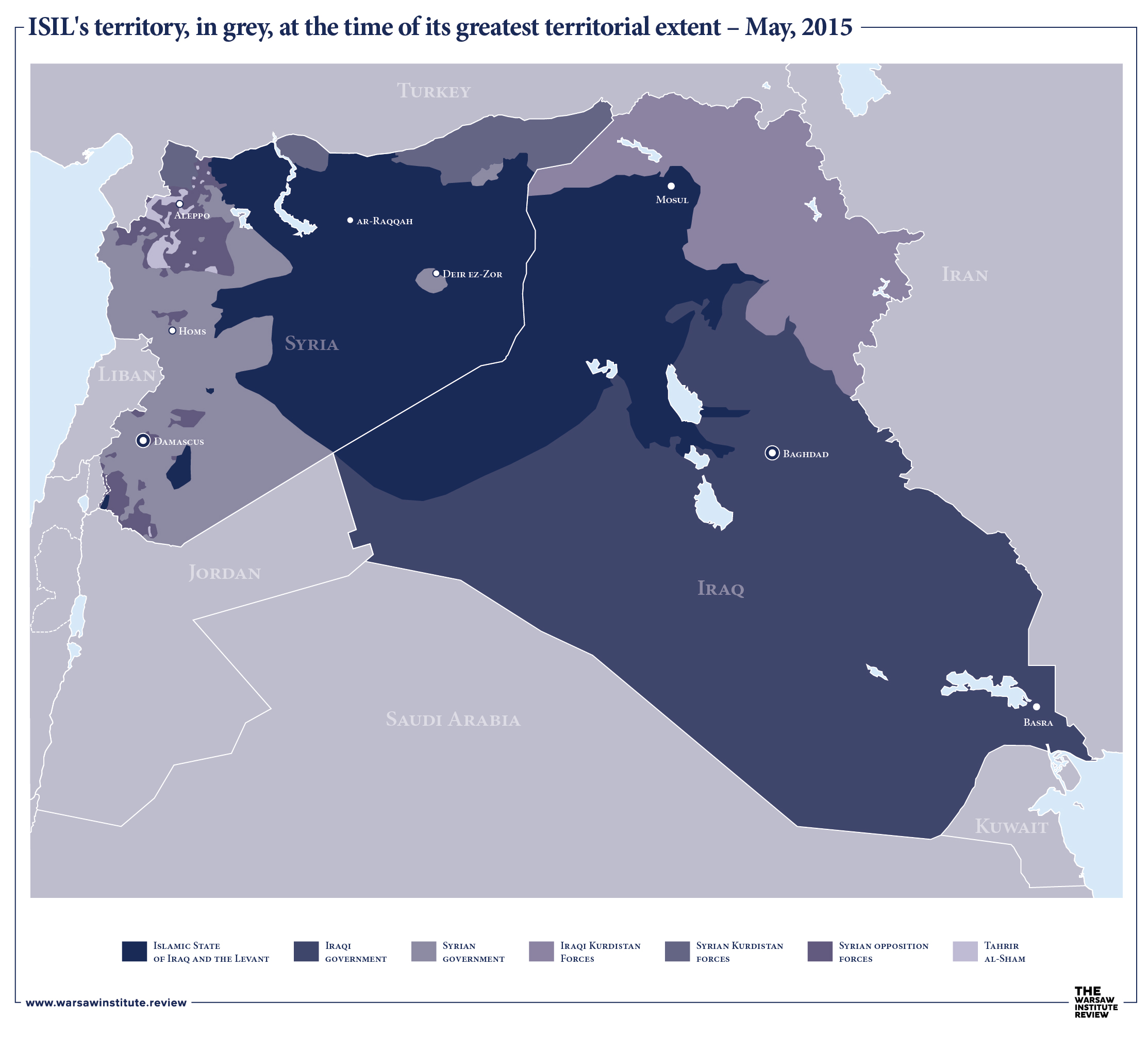

At its height in 2014–2015, the so-called Islamic State waged war both on Syrian and Iraqi fronts. But this is a rather simplistic vision –– if we overlay an ethno-religious grid onto a map of attack directions, it is vital to distinguish the jihadi invasion on the two Kurdistans – Syrian and Iraqi. Before launching a massive attack in the direction of Iraq, jihadi militants had taken advantage of the Syrian civil war to build their position and base, as well as expand their “territorial depth.” What is alarming is both the scale of their genocidal crimes, and the military momentum al-Baghdadi’s forces had when besieging subsequent cities. The ISIL-led war campaign began when the caliphate deployed some of its experienced Iraqi jihadist insurgents to Sunni-inhabited lands with a mission to form coherent military groups, train terrorists and launch an offensive operation.

Of all regions, al-Baghdadi’s loyalists were most active in the provinces of Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo, and Idlib, with an exceedingly skillful tactic being adopted since the very beginning. The fighting over the Euphrates River proved that ISIL first provoked conflicts to be then able to gain profits from disputes smoldering on a given territory; they have targeted both the Damascus-loyal government forces and Kurdish-led military units in Rojava, the autonomous region of Syrian Kurdistan, while facing off rebel factions of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and other jihadi-like groups like the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat An-Nusra. When fielded to the Syrian front line, ISIL sought to wage war against virtually anyone while plotting intrigues and enfeebling its theoretical allies. Though this study refers chiefly to Iraq, the Syrian example exhibits that the civil war absorbed –– either directly or not –– both local and global powers, from Turkey and Saudi Arabia, through Iran, to Russia, the U.S. and France), where ISIL has yet emerged as a belligerent party. The Syrian conflict morphed into somewhat an ethnic and political Gordian knot, a situation that for a few years was much to the liking of Islamic insurgents.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of al-Qaeda who succeeded Osama bin Laden following his death, voiced criticism over al-Baghdadi’s “doctrine,” and these two terror groups eventually drifted apart. Interestingly enough, al-Qaeda might have seen Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as responsible for “dirty work,” the man whose actions could eventually be restrained on Syrian soil. Perhaps al-Baghdadi masterminded a great mystification since the dawn of the Syrian civil war, seeking first to form some unspecified jihadi groups –– initially intended to conceal their radical nature –– in a bid to impose the bloody Sharia rule and pledge loyalty to his figure once his faithful insurgents conquer and win control of the territory. To a large extent, he managed to accomplish its goal.

Also, al-Baghdadi spoke in favor of merging the two terror groups. But a rift within a “jihadi family” saw ISIL –– an organization viewed as more affluent and stronger –– taking over both personnel and assets of any affiliates of al-Qaeda or other radical factions. Along with ISIL’s territorial expansion, jihad “volunteers” aspired to swell the ranks of the so-called Islamic State, instead of any other rebel grouping. What raised the militant group’s attractiveness in the eyes of Islamic fanatics was a new propaganda model, with a large-scale social media campaign. On the tide of “retaking” lands from FSA and an-Nusra rebel fighters, ISIL took complete control of Raqqa by January 13, 2014, later the capital of the self-declared “caliphate.” ISIL succeeded in joining together a great deal of hotbeds around Syria’s eastern provinces, mainly in the Islamist-occupied region of Raqqa, part of Aleppo province, Deir ez-Zor region –– yet without the city itself –– all of which laid the groundwork for the self-styled caliphate. The geographical scope of the jihadist attacks is evidenced by the fact that the Kurdish town of Kobane, known under its official name of Ayn al-Arab, which the terrorists besieged from September 15, 2014, to March 15, 2015, is located on the Syrian-Turkish border.

The expansion of the so-called Islamic State in Iraq

With the fighting to secure ISIL’s base on Syria being underway, militants launched an offensive in Iraq. ISIL militants preyed on the Sunni-Shia conflict that rattled Iraq for a couple of years, though remained dormant since the dawn of the said statehood. When second time in office between 2010 and 2014, Iran-backed Shia Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki faced accusations of downplaying and discriminating against the country’s Sunni-inhabited regions, purges in the army and ministries and personnel reshuffles, to the benefit of the Shia population. What occurred as the boiling point was the outbreak of mass protests within Iraq, sparked by the Sunni Arab population, were deadly clashes that swept across the town of Hawija in April 2013. Ethnic and religious divisions –– already apparent at that time –– eventually gained never-before-seen momentum, morphing into a political front line. Meanwhile, al-Maliki’s cabinet underwent further political purges while an ambitious U.S. Army project aiming to drag Anbar-based Sunni tribes to the side of the government was abandoned. Al-Maliki recognized such militias as a threat. The U.S. was pulling its military continent out of the country. This was so much to the liking of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Driven by the Sunni Arab insurgency in Anbar province in December 2013, al-Baghdadi’s loyalists began to put into action an extensive plan for an Iraqi offensive. In early January 2014, they at least partly asserted control of the border town of al-Qaim, Fallujah, Karmah, al-Khalidiya, Haditha, Saklaviya, Ramadi and Abu Ghraib. ISIL’s incursion flashed the first urgent warning for the Iraqi government, given that the Islamist-seized town of Fallujah is located on the outskirts of Baghdad, just an hour’s drive from the country’s capital. Anbar province and even Bagdad Governorate were set on fire.

While the ISIL momentum and its territorial claims stirred the imagination of residents of the Middle East and experts interested in Iraqi affairs, reports on the militant group’s seizure of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, profoundly shocked the world. Especially that the circumstances of the fall of Mosul could have been taken as a bad omen for the further fight against jihadi insurgents. On June 5, 2014, militants from what was then known as ISIL launched an assault against the rich city of Mosul, the main urban area in northern Iraq. The Iraqi government army had 30,000 soldiers and officers, and troops from the 2nd Infantry Division and the 3rd Motorized Division of the Iraqi Army were deployed to defend Nineveh. Roughly 1,500 jihadists were fielded to seize Mosul. Yet, by June 9, Iraqi troops and police officers deserted the battlefield while Islamists marched into the city. Speaking from the podium of Mosul’s Great Mosque of An-Nuri on June 29, the first day of Ramadan that year, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced the establishment of the so-called Islamic State and proclaimed himself “Caliph” Ibrahim.

The seizure of Mosul paved jihadists’ way for a military offensive and the conquest of the Nineveh governorate in August later that year. Also, jihadi fighters captured the Iraqi city of Tikrit, known as the capital of the Saladin governorate and the birthplace of Saddam Hussein. After the escape of Iraqi troops and police officers, a political vacuum emerged in the Nineveh Plains, a strip of no man’s land where fled thousands of displaced war refugees. At that point, Iraqi Kurds joined the operation –– Kurdish forces known as the Peshmerga marched out of the autonomous Kurdistan Region (KRG), quickly filling the void left by Iraqi government forces. Territories where jihadi militants clashed with Kurdish forces are referred to as “disputed,” what could be called a “bone of contention” between Erbil, the capital city of Iraqi Kurdistan, and Baghdad. Though of little importance back in 2014, the dormant Iraqi-Kurdish conflict could resume much earlier than anyone might expect.

As a result of the fighting, the front line between the so-called Islamic State and Iraqi Kurds eventually leveled off. ISIL jihadi insurgents imposed their bloody rules and started executing the Christians, Yazidis, and Shias. They forced the Assyrians, the Christian minority indigenous to northern Iraq, to convert to Islam, while men were murdered and women raped. The terror group was also reported to be extracting jizya taxes – a humiliating levy forced upon the Christians. Following the capture of the Yazidi-inhabited region of Sinjar, local women and girls were sold into slavery, the fact that I have mentioned above. The slave price list blatantly shows how perfidious and sadistic ISIL jihadists were. In 2015, Zainab Bangura, the U.N.’s Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Sexual Violence in Conflict, said young children, up to the age of nine, fetched around $165, adolescents –– $124, while women generally fetched lower prices as they got older. Jihadi militants enforced their strictly extremist-interpretation Sharia law in the conquered areas, depriving women of their rights and banned music and smoking, the latter of which is popular in the Middle East. The brutal rule of the so-called Islamic State involved severe punishments like public flogging or crucifixion. Though seen as a quasi-state creature, al-Baghdadi’s “caliphate” imposed a totalitarian regime, with a vast machine of repression and terror. At its height, the “caliphate” stretched:

– from Sinjar to Mosul in northeastern Iraq, through vicinities of the city of Kirkuk in the east, to Fallujah and Baghdad’s outskirts in the southeastern part of the country – from the outskirts of Aleppo in northwestern Syria, through Kobane in the north to Syria’s western governorate of Hama and the city of Palmyra.

It is estimated that al-Baghdadi had eight million people in territories under its control, said to be roughly the size of England. Even if overestimated –– with some saying that at its height, ISIL controlled just over 90,000 km2 of land –– the terror group brought to life a quasi-state that destabilized the whole region of the Middle East, cutting Iraq off the Syrian and Jordanian borders. ISIL became what could be called the world’s wealthiest terror group, looting 500 billion Iraqi dinars — $429 million –– from the Iraqi city of Mosul, and seizing oil-rich areas.

Bagdad in the face of the jihadi offensive

The fall of Mosul shocked namely also the country’s Shia political elites. In the face of such a major military defeat, Nouri al-Maliki’s position was weakening day by day. On June 13, 2014, Ali as-Sistani, a prominent Shia cleric, urged people to take up arms against Sunni-led insurgents, calling on Shia youth to join militia branches, later known as the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU). Similar calls were raised by influential Shia religious leader Muqtada as-Sadr. On June 11, Tehran sent to Baghdad troops from the Quds Force, an elite unit in Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The ISIL expansion on Iraqi soil coincided with the country’s political deadlock at home. It was only in July that Fouad Masum, an ethnic Kurd, was approved as president after the April presidential vote. Theoretically, al-Maliki could form his next cabinet, though in the face of worldwide pressure and military defeats, he was succeeded by Haider al-Abadi. Not only was Nouri al-Maliki accused of having lost the political campaign in 2014, but also of antagonizing the country, and –– most importantly –– the newly formed Iraqi government, due to its shaky position, and had to restore relations with Washington. Maliki held responsibility for running an anti-American campaign, making his best efforts to pull U.S. military contingent out of the Tigris River. In a last-ditch solution, he could hope to ask Tehran and Iran’s theocratic system for help. When Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, eventually lent support to al-Abadi, former prime minister al-Maliki resigned himself to the loss of office. The change in power in Iraq was warmly welcomed around the world, especially by the countries of the Middle East: Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other states of the Arab League. In its war against the so-called Islamic State, Baghdad was supposed to get help simultaneously from Washington and Tehran.

Washington’s perspective

Back in time, then U.S. President Barack Obama downplayed the significance of the ISIL case, saying the terror group included some low-level terrorists. However, everything changed in August 2014 when the world discovered how “the caliphate” pursued its offensive in the Nineveh Plains, where jihadi militants raped, executed, and abducted mainly Christians and Yazidis. Seeing 150,000 Christians fleeing Nineveh province, primarily to Iraqi Kurdistan, and the escape of defenseless Yazidi population into the mountains of Sinjar, Washington launched an international military and humanitarian intervention. From the beginning, the operation involved air forces and special operations, with the participation of commando forces, artillery, training component, and humanitarian aid. Once deployed to the field, they solved the problem of the “boots on the ground” doctrine, seen by U.S. society as highly unpopular, while allowing them to engage in the conflict. In October 2014, the intervention –– being underway at that time –– came to be officially known as Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF–OIR), an ad hoc contingent taking part in the mission, was deployed mainly to the Iraq theatre while also encompassing Syria. Reports say that U.S. Air forces carried out up to 80 percent of all the air strikes as part of OIR, and the remaining 20 percent – by U.S. allies – the United Kingdom, France, Canada, Netherlands, Belgium, and some regional actors, among which Turkey, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates or Jordan. The Global Coalition against Daesh was formed, at that time comprised of 70 countries (the coalition is still expanding). Iran, which carried out its own operation in Iraq, was not included as part of OIR. What surged as a decisive moment for the international coalition was a Mosul offensive, or a military operation with an aim to liberate Mosul and whole Nineveh province from the yoke of the so-called Islamic State.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

The U.S. ensured patronage under the operation, providing cutting-edge military hardware, especially aircraft carriers. The land operation was undertaken by two armies –– Iraqi Security Forces (ISF), backed by the PMU and some other military branches, including the mainly-Christian Nineveh Plain Protection Units (NPU) and the Kurdish Peshmerga, fighting alongside local Christian military groups: the Nineveh Plain Forces (NPF) and Dwekh Nawsha. Combined all together, the above forces numbered more than 100,000 militarymen, managing to accomplish their assumed goals during roughly ten months of the campaign (October 16, 2016 – July 20, 2017). The U.S. military involvement and the success of the operation paved the way for halting Iraqi-Kurdish resentments on these two’s disputed lands. Also, this permitted to indicate where to attack and break through the defense cordon of the so-called Islamic State and cleanse the shame of the Iraqi army after a defeat it suffered back in 2014. This helped rebuild Baghdad’s credibility and kick off a broad operation intended to liberate Syria and Iraq from the jihadi scourge. The U.S. policy, for its part, redefined the presence over the Tigris River. While deploying troops to Iraq did not meet with wide public support, members of society approved the purpose of the fight against the terror group, along with how it was carried out, by relieving land forces of its military tasks. Among those who involved in the operation against the Islamic State was U.S. freshly elected President Donald Trump, who took office in January 2017. Though Trump is far from being branded as a proponent of U.S. military involvement in the Middle East, the war against ISIL was high on his list of priorities. He introduced changes in both how financial support was distributed to Syrian insurgents and “Obama’s doctrine,” depriving unpredictable Sunni (jihadi) groups of help to the benefit of the Kurdish-led stable coalition of SDF.

Erbil perspective

Whilst this analysis does not encompass the assessment of the U.S. invasion in 2003, both journalistic sources and more insightful studies put the U.S. Army’s presence in Iraq in the negative light, depicting the conflict itself as an overall failure. Though ridiculed by experts for years, Operation Iraqi Freedom genuinely brought freedom to the Kurds who seem to see the whole undertaking positively. In 2003, the Kurds confirmed their autonomy, by de facto establishing their own state having its disposal territory, services, army (Peshmerga forces), administrative structures (Kurdish Regional Government, or KRG), and parliament that empowered Kurdistan to push forward its economic and diplomacy policies, independently of Baghdad. What lacked was a pro-forma recognition of autonomy as an independent state. Kurdistan’s local politics fractured into the two clan-affiliated parties: the Barzani-controlled Kurdistan Democratic Party (PDK) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), held by the Talabani family. Under Iraq’s constitution, the president must be a Kurd, and the prime minister a Shia, a solution to regulate ethnic strains, which is why subsequent heads of the Iraqi state welcomed the Kurds on the country-wide political stage. Though from the autonomy’s perspective, its split with Baghdad only beefed up as Iraq cut off oil deliveries to Kurdistan, though following the escape of Iraqi forces in 2014, Kurdish Peshmerga forces captured the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, claiming its historical ties to the region. Since 2003, when Iraq suffered an economic collapse, the Kurdistan region saw the development of its economy, attracting groups of investors.

To prove Kurdistan’s absolutely sovereign policy, suffice it to cite an example of an agreement between Masoud Barzani, the President of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, and Turkish President Recep Erdogan, with Ankara surging as a top economic partner for Erbil. In 2016, Turkey’s exports to the KRG were $5.4 billion, compared to $7.6 billion for Iraq in total. For Erdogan, Erbil became a leading partner in trading oil and natural gas. Although Erdogan is enforcing a drastic anti-Kurdish policy, he did not mean to target Iraqi Kurdistan or the Kurdistan Democratic Party –– instead, he sought to strike a blow to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Rojava-based People’s Protection Units, or YPG. The PDK even invited the Turkish military mission that trained the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, a step that Baghdad saw –– without its prior consent –– as the admission of foreign troops into an integral part of Iraq.

Iraqi Kurdistan launched its secessionist process on a tide of Peshmerga’s direct participation in the fight against the so-called Islamic States and beefing up its independent position across the country. But even Kurdistan’s good relations with Turkey and Iran and bordering with the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS) –– a de facto autonomous region inhabited by Syrian Kurds who, though themselves did not struggle for independence, saw the entire process positively –– as well as autonomy of Baghdad could no longer bring well-preserved geopolitical deals to a halt. KRG’s secessionist endeavors were yet stopped by their neighbors’ blatant stance on the Kurdish minority. An independence referendum for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq was held on September 25, 2017, with final results showing 91.8 percent of votes cast in favor of secession. The vote triggered off a series of strong reactions against Erbil, while Israel emerged as the region’s only country to back sovereign Kurdistan (as part of the Kurdish autonomy in Iraq). This drew sharp reactions from both Ankara and Tehran. Iraq’s Supreme Federal Court ruled the Kurdish independence referendum was unconstitutional. Four days after the referendum, the Iraqi government stopped most international flights into the two international airports of Erbil and Sulaimaniya. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi urged the Iraqi military to launch an offensive against the KRG.

Between October 15 and October 27, 2017, Iraqi units reclaimed all the lands that Kurdish Peshmerga forces had seized while fighting against ISIL. What was particularly valuable was regaining control of the city of Kirkuk and its oil-rich vicinities. The Iraqi army claimed the disputed lands that were to be voted on during the referendum. Iran blocked border crossing with the KRG. Not only did Erbil have to recognize its military defeat, but it also lost some of its autonomy (e.g., border control) it had enjoyed prior to the referendum. After the Iraqi-Kurdish war and the ultimate failure of Kurdistan independence attempts, Masoud Barzani, who since 2005 had served as the president of the KRG, resigned from his post.

Baghdad perspective

Ahead of the incursion of the so-called Islamic State in Iraq, the country-wide political stage witnessed the domination of Shia politicians, with ever-growing support from Iran and its influence on the balance of power in Baghdad. The war against ISIL intensified Baghdad-Tehran ties, but the country saw a series of personnel reshuffles in nation-wide politics. On August 11, 2014, Haider al-Abadi was named as new prime minister. He changed the manner in how Iraq was perceived worldwide while masterminding an effective, albeit lengthy and bloody, the offensive against the so-called Islamic State. Al-Abadi –– who completed his Ph.D. at Manchester University, removed al-Maliki from power, and trumpeted the end of the jihadi rule over Iraq (though this was a premature conclusion, after the Iraqi military entered the rubbles of the Great Mosque of an-Nuri in Mosul, blown up by jihadi militants in June 2017) –– was seen throughout the world as a natural game-changer for Iraq’s domestic political stage. Al-Abadi turned into a West’s favorite –– but as it was the case before –– the world failed to bear in mind what moods prevailed in Iraqi society.

Held on May 12, 2018, the parliamentary election surprised worldwide public opinion with its results. Media initially reported on the triumph of al-Abadi’s Victory Alliance. But it was Muqtada as-Sadr, an eminent Shia cleric, emergent triumphant in the vote, whose party forged a political alliance with Iraq’s Communist Party, which may sound strange for a Polish reader. His Sairoon alliance won 54 seats in the parliament while al-Abadi’s coalition came in third, securing 42 seats. Interestingly, in his election campaign, as-Sadr blamed the country’s elites for bribery while voicing criticisms against the U.S. (as-Sadr’s Mahdi Army was behind an anti-U.S. rebellion in 2004), and Iran’s policy on the Tigris River, the last of which surprised many. As-Sadr’s followers called for forming a technocrat cabinet, without any affiliations to the outside, and in 2016, they stormed Baghdad’s Green Zone in an apparent bid to demand political changes in the country. The war against ISIL revealed a change in social moods, of which Muqtada as-Sadr took advantage when boasting his independence. However, this did not imply that a pro-Iranian party stepped down from the Iraqi political stage. Quite the contrary, it only gained momentum. The anti-ISIL military offensive gave rise to the establishment of the PMU –– an umbrella organization of predominantly Shia paramilitary groups –– viewed as military, yet not so much political, force.

In the 2018 elections, the Fatah Alliance, the PMU’s backbone led by Hadi al-Amiri, earned 48 of the seats in Iraq’s parliament. The U.S. special envoy for the Global Coalition to Defeat Daesh branded al-Amiri, a commander and member of the Iraqi parliament, as “the most powerful and pro-Iranian.” An army of Shia militia, estimated to comprise between 60,000 and 150,000 fighters, morphed into a critical support tool in combatting ISIL in Iraq, albeit it poses a thorny problem for Iraqi politicians. A levy en masse –– once furnished with weapons –– cannot be demobilized so quickly, serving as an armed arm of various factions. Politically, it is impossible to conduct an operation against the PMU, though Shia militias are mighty enough to exclude such an option from a military perspective. In March 2017, the Iraqi military began operation with a mission to include the PMU as its special forces component. Among those who called for boosting integration efforts was even Ali as-Sistani. Nonetheless, private armies of Shia politicians are their substantial assets in Iraq’s dirty political game. The PMU has taken its toll on geopolitical issues, with a possible threat from Shia militias serving as the key reasons for evacuating U.S. diplomatic missions in Baghdad and Erbil in May. The PMU is far from being homogenous, while the Fatah Alliance enjoys support from the Badr Organization and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH). After the parliamentary vote, Adil Abdul-Mahdi was named Iraq’s prime minister and formed a new technocrat cabinet –– a stipulated by as-Sadr’s followers –– upheld by both Sairoon and Fatah.

Warsaw perspective

In 2004, Muqtada as-Sadr, who is seen today as Iraq’s mightiest political leaders, staged an uprising, with the heaviest fighting taking place over Karbala’s City Hall. The Poles, together with Bulgarian soldiers, were given the task of defending the municipal hall. Between April 3 and April 6, Polish and Bulgarian troops managed to protect their positions, with no losses for either. The cleric-led rebellion eventually suffered a defeat from coalition forces. What occurred back then did not place a burden on Polish-Iraqi ties –– Warsaw and Baghdad maintain good relations, while the Polish government engaged in the fighting against the so-called Islamic State, also in Iraq. Instead of providing combat missions, Poland contributes to the training of local military forces. Being part of the Global Coalition to Defeat Daesh, Poland dispatched two of its contingents: the Polish Military Contingent, or the Polski kontyngent wojskowy (PKW) OIR Iraq –– a special forces training component, supplemented by logistics and technical unit, as well as the air reconnaissance mission tasked with performing its duties over the ISIL-occupied lands of Iraq (including Mosul) –– as part of the PKW OIR Kuwait. A Baghdad-based Polish training mission has had the task of instruct Iraqi repair crews for Soviet-built equipment, still used in the military’s stockpile of Iraqi armed forces. By providing direct training for soldiers and military staffs, and technical support for crews in tanks and armored carriers, Polish troops and special forces can exchange their experience while offering tangible support for the ISF in an effort to boost the military’s quality. Furthermore, since Poland’s Law and Justice –– United Right came to power in the 2015 parliamentary vote, Warsaw has opted for lending relief assistance to victims of the war in conflict-affected areas while supporting those in need by repeatedly increasing humanitarian aid. Thus, Poland lends practical support for both Iraq, and the victims of ISIL, by funding module houses for the internally displaced, building livestock farms, reconstructing workplaces and offering medical and education aid for the local population.

Conclusions

ISIL’s expansion and occupation of Iraq (2010–2017) sparked off several threats, both to Baghdad and the entire region. The self-styled “caliphate” rolled up the already existing process in Iraq, among which are backing jihadi militants by the country’s Arab-Sunni part and the political dominance of Shia-led movements. Thus and thus, ISIL accentuated smoldering conflicts within Iraqi borders. The war against ISIL brought Iran’s role to the foreground while there reemerged the issue of halting a plan to pull U.S. troops out of Iraq. Eventually, in order to combat al-Baghdadi’s loyalists, Washington had to endorse Iraqi government forces and Kurdish Peshmerga. The war against ISIL failed to topple a set of long-rooted geopolitical vectors in the Middle East –– on the contrary, it kept them up, as one could see the Kurds, who tragically deluded themselves into thinking that the world’s sympathy amid its fighting against ISIL would morph into approval for their secessionist aspirations. Iraq still has to grapple with a series of challenges that ISIL has left behind. In addition to ethnic, religious, humanitarian and military aspects mentioned above, there is still such a commonplaces issue as educating younger generations after years of ISIL domination. In the lands that were under ISIL rule, jihadi insurgents imposed their interpretation of Sharia indoctrination in garrison-like schools, training adolescents to become suicide bombers. These youngsters still inhabit the same territories. What poses yet another problem is the issue of children born to ISIL fighters; the Iraqi justice system is probing on ISIL militants and their associates, among whom are foreign passport holders who came for jihad. For years, Iraq has been part of a larger geopolitical theater in the Middle East, with the war against ISIL coming as its yet another chapter. These challenges should not be considered trivial from a geopolitical perspective. The Middle East is fearful of the resurgence of an “Islamic State 2.0”, while the flood of jihadi volunteers, also from Europe, is still high on diplomatic agenda. The countries of the Middle East have a problem with the jihadi fighters, while Europe fails to acknowledge their presence.

Recommendations

To ensure Iraq’s development and future, what seems the sole legitimate advice is an alliance transcending any divisions, with full respect for ethnic and religious minorities. An example of this can be mainly seen during the manifestation in Baghdad. Otherwise, the country will slowly yet inevitably drift toward the disintegration into three parts that emerged during the ISIL expansion: Sunni, Shia and Kurdish. The caliphate’s rule is nevertheless still a painful lesson for Iraq’s Arab Sunni regions which bears the brunt of lending support to al-Baghdadi’s terror group. Shia factions should learn the lesson from the aftereffect of the policy of isolating Sunnis. There is no other path than forming a legitimate government of “national unity,” unless this is, of course, not merely a political phantasmagoria . ISIL is still killing people, therefore the Global Coalition has its raison d’être while anti-terrorist operations are currently underway on African and Asian fronts. Western European governments should draw lessons from maintains security, as their unreasonable tolerance for illegal border violation sparked off the migrant crisis. Alongside other refugees heading to Europe were also ISIL-affiliated militants. The threat of such “escapes” has only drawn nearer in the face of the “caliphate’s” territorial collapse.

The basis for easing tensions in the Middle East and establishing peace across the region are pragmatic undertakings: rebuilding cities and villages, hospitals, workplaces while offering support for civilians undergoing the process of independence. What serves as an example of a realistic policy towards the Middle East are actions taken by the Polish government. Poland’s relief assistance for victims of ISIL has attracted attention worldwide, while at the Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom (MARF) conference in Washington, speakers from Poland were requested to present their achievements in humanitarian and development aid. Iraq will grab the attention of both the region’s countries –– Iran, Turkey, Syria, Saudi Arabia –– and the global powers: Russia and the United States. It remains an open question, however, how successful Baghdad’s attempts will be to become a subject and not an object of worldwide politics. The years-long war waged against ISIL has only underscored the meaning of this question.

_________________________________

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.