THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 4 December 2019 Author: Alexander Wielgos

Afghanistan’s Chance

It might not feel like it from the headlines, but Afghanistan is ready for peace. The circumstances and timing will never be absolutely perfect. Certain dynamics may be pressuring a potential turning point, and the circumstances might just become good enough for a step towards peace – for the first time since 1978. Implications thereof are further explored in an interview with the Ambassador of Afghanistan to Poland.

Firstly, the stagnation of peace negotiations between the US and the Taliban in Qatar may or may not be only temporary, as hinted on 28.11.2019 of resumption of informal talks. Rivalling entities Russia, China, Iran, and others, have been attentively seeking to present themselves as credible alternatives in mediation, adding some real but limited pressure. Secondly, there is an unobvious potential of further fracturing in the Taliban, in the backdrop of resilience of ISIL KP and other armed terrorist groups. Thirdly, albeit dismally far from optimal, the ongoing counting of the recent Presidential elections do reflect how far socio-political reform in Afghanistan has come in the meantime. Fourthly, what conclusions local and international actors draw from their observations will impact how they understand the status quo on the geopolitical chessboards they are positioned in. It thence shapes how they think they ought to operate, and a combination of shifts in the correct directions could be aptly creating Afghanistan’s chance for peace.

Poland too , as a close partner of the US and part of NATO Operation Resolute Support (RS), is observing those observing Afghanistan’s potential turning point. Poland’s input need not be massive, it just needs to be clever. Strategies encouraged ought to be a showcase of the good of humanity, most especially in a chapter where it is so obscure and devoid of optimism.

Recap

If you need of a quick recap on some of the lead up to what it is that is being observed in this context, you’re in luck: Afghanistan has been in a constant state of conflict since 1978 – that’s over 41 years at the time of writing this article.

Afghanistan’s monarchy was removed in 1973 by the monarch’s cousin , Mohammed Daoud Khan with the help of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Daoud feared attempts of the USSR and Iran to influence domestic affairs, and noted in 1974 as India tested its first nuclear weapon , dubbed the ‘Smiling Buddha’. Daoud Khan led a Pashtunisation approach with regard to the Durand Line , and reformed Afghanistan’s military, which included training Baloch soldiers against Pakistan. By then, Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the ISI, had already begun covert operations in Afghanistan, including establishing ties with a Hekmatyar Gulbuddin. Though Afghanistan’s relations improved meanwhile with Pakistan and Iran, as well as Egypt and Saudi Arabia with the help of the US, this concerned the USSR, and Pakistan’s covert operation-related plans did not go to the dustbin.

In 1978, dissatisfied with Daoud’s resistance and fearing he had begun removing internal opponents in the PDPA, the Khalq faction of the socialist PDPA party killed him as they carried out a military coup; the Saur Revolution. Following rebellions across Afghanistan, including in Farsi speaking Herat, made the US quite convinced that intervention from the USSR was both likely and to be dreaded. The US co-opted with Pakistan as improved relations were needed in light of the Iranian Revolution. Hence, limited US support via Pakistan for Mujahideen had begun since just before the USSR invasion.

This support quickly upgraded to propping up an array of factions within the Sunni Mujahideen insurgency. Some largely were independent and moderate, such as those led by the ethnic-Tajik Ahmad Shah Massoud, and some were particularly favoured by Pakistan, such as Hekmatyar. Saudi Arabia also selectively made contributions, to groups such as Ittehad-e Islami and allegedly, the Haqqani Network . Most notably, the Haqqani Network were the first to have brought in foreign fighters into Afghanistan from various countries, demonstrating their ideological understanding to draw better financing than other organisations. Meanwhile, Mujahideen Shia factions, namely of the Hazara ethnic group, merged into the Hezb-e Wahdat and were supported by Iran, though Iran was mostly preoccupied with Iraq at the time. Maoist groups also emerged in the war. Along the way, an offshoot of the Sunni Mujahideen appeared at some point in 1988, which became al-Qaeda, with an ideologically globalised rhetoric of the Haqqani Network’s. Eventually, the USSR withdrew in 1989, and support was reduced to arms supplies. The socialist PDPA government faltered against the unrelenting Mujahideen factions, and fell in 1992.

Entering a new phase of the civil war, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Uzbekistan each intensified their arming of proxies vying for domination via a combination of deal-making and application of violence. The Hezb-e Islami faction, led by Hekmatyar, refused to collaborate with other Sunni Mujahideen groups.

Hekmatyar had received more from the CIA via the ISI than any other Mujahideen leader, despite his anti-US stance. Yet, Hekmatyar bombarded Kabul in 1992 in an attempt to seize it. In a bizarre twist, one of those rockets hit the building where Hamid Karzai was a political prisoner, after which he could escape . The bombardment caused massive civilian casualties and unpopularity. Pakistan switched its support to the Taliban, which emerged at some point in September 1994, proceeded on to seize Kabul in 1996, and then to consolidate control of most of Afghanistan by 1998.

Though the power struggle continued, the 3 other main factions lost their entire territorial control, with the exception of the Northern Alliance, also referred to as the United Front. It included Mujahideen commanders such as Burhanuddin Rabbani, a Tajik leader from the north; Haji Mohmmad Mohaqiq, a Hazara leader from Mazar-e Sharif; Haji Abdul Qadir, a Pashtun leader from Jalalabad; as well as Ahmad Shah Massoud, whose men had been tortured to death by Hekmatyar’s; and General Abdul Rashid Dostum, with the Uzbek Junbish-e Mili militia . Iran, Russia, and India supported the United Front against the Taliban, but Iran stopped short of an invasion after 11 Iranian diplomats in its Mazaf-e Sharif consulate were killed in 1998 by a militant group, perhaps noticing Pakistan’s nuclear tests.

After 9/11, as the Taliban refused to give up al-Qaeda, the US-led invasion of Afghanistan began in October 2001 and quickly unseated the Taliban, which was by all means the correct move. The US, the international community, and Afghan leaders who opposed the Taliban, including those from the United Front, had the challenge to create a new Afghan state. Note that Hekmatyar was excluded from the Bonn Conference in December 2001. NATO formalised its mission then as the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan to secure Kabul to enable the establishment of interim and transitional Afghan governments, in phases. Based on UN Security Council Resolution 1401 of March 2002, the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) was established to back these efforts.

The Taliban persisted with a retaliatory insurgency, as did other groups. Their experience from preceding conflicts suggested using a variety of asymmetric war tactics in the face of being egregiously overwhelmed militarily. This included an influx of foreign fights facilitated by previous instances. Accessible regrouping locations along the porous border of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa areas of Pakistan became a key contention point in Pakistan’s relations with the US and Afghanistan. Moreover, the insurgent’s familiarity with Afghanistan’s mountainous terrain enabled the insurgent factions to be infuriatingly evasive.

From the mandate of UN Security Council Resolution 1510 of 2003, the ISAF expanded its mission beyond Kabul and repeatedly broadened its objectives beyond the counter-insurgency. This was necessary to preserve gains made thus far. However, it slowly began to be increasingly clear that these aims in the direction of nation-building, training the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), etc. were vaguely defined. This year, many US resources were also reallocated to Iraq.

Unfortunately, a lacking understanding of the weight of local tribal, ethno-religious politics, their traditional autonomy, and Afghanistan’s traditional resentment of foreign meddling, hindered efforts to make such a nation-wide transformation possible. Additionally, incorrigible levels of corruption not only lingered within the ANSF and government, but supposedly even worsened, and an uncontrollable opium production sustained a portion of Taliban war funding.

Prolonging the cumbersome, stagnant and rescinding war effort unfortunately causes increases in the already staggering civilian death tolls and human rights abuses from the anti-government factions, who deliberately target civilians directly in mass attacks and suicide bombings, or seamlessly blend amongst them to incur additional casualties, if not deterrence. Unfortunately, the NATO side and the ANSF had also inflicted damage unto civilians during operations. Perhaps neither the most common nor damaging, but probably one of the most demoralising incidents were those of internal fire; cases where NATO-supported ANSF troops would turn on NATO forces or their colleagues.

The need to bring the war to an end became clear, but how to do so became just as equally unclear. The alternative is a high-casualty, destructive and costly militarily stalemate seeking an outcome with ambiguously defined means to strive for it whilst also preserving the positive accomplishments already made.

A Peace Process Stagnated

In September 2007, then President Karzai publicly offered peace talks to the Taliban, which they rejected, saying foreign troops suggest the Afghan government is but a puppet. The offer was extended also to Hekmatyar. How an end to conflict may look like took centre stage of campaigns to the 2009 Presidential Elections, attesting to widespread consensus among the public and government circles of its priority. An early attempt of Saudi Arabia to mediate had stalled.

Karzai had then secretly met with Abdul Ghani Baradar, the Taliban’s second-in-command at the time, at least a few times. Baradar, the enthusiast for negotiations with the Afghan government and the US who avidly persuaded such, however, was detained in February 2010 in a joint US-Pakistani raid in Karachi, Pakistan.

The US continued increasing deployments to about 100,000 by August 2010, with the ISAF total reaching 140,000. Notably, Osama bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in May 2011 during a separate precise US operation, which was an important, albeit more symbolic accomplishment. At this stage, al-Qaeda had long spread further across several countries across several regions, in which they operate independently under a common ideology.

Thus far, the impasse pertained to the Taliban refusing the negotiate with the Afghan government, and the US refusing to negotiate with the Taliban. Shortly after the surge, however, a first turning point in what could be considered the Afghan Peace Process was the US announcement of a timeline for withdrawal plans from Afghanistan aiming for 2014. Note: at this time the US is also set to withdraw from Iraq. Regrettably, the signal to the armed anti-government insurgent terrorist groups was clear: the US is seeking an exit strategy, conditions are ripe to begin a resurgence in operationality and simply wait them out. Rather than indicating their defeat, it unavoidably empowered the Taliban morale.

This made neither the Taliban nor the US keen negotiate with one another, refuting the possibility and naming clearly unattainable demands for talks. With reference to said impasse, for the Taliban the condition was that if they were to negotiate, it would be with the US directly without the actual Afghan government, but the US would not negotiate with what is, in the end, still a designated terrorist organisation.

Despite hesitation, as early as some point in 2011, secret talks, confidence building measures, were rumoured to have taken place in Qatar between US officials and some Afghans who indirectly represented the Taliban. Because this leaked , however, whether intentionally or not, the talks collapsed.

Later, in mid-2013, with agreement from the US, a Taliban representative office was opened in Doha, Qatar, to facilitate dialogue between the US and the Taliban. Less than a month later in July 2013, it had to be closed because the Taliban used their pre-2001 Islamic Emirate flag, exploiting the situation to falsely present themselves as an alternative government or government-in-exile seeking legitimacy.

Mounting valid worries that the Afghan government would be sidelined are more than understandable. Even worse, it shows a precedent that Afghan civilians are completely excluded for prospects of what could lead to peace talks. Following Saudi Arabia’s earlier attempt, a four-way international conference was held in Pakistan in January 2016, though boycotted by the Taliban. Seeing this did not work, another secret meeting followed in October 2016, this time informally between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

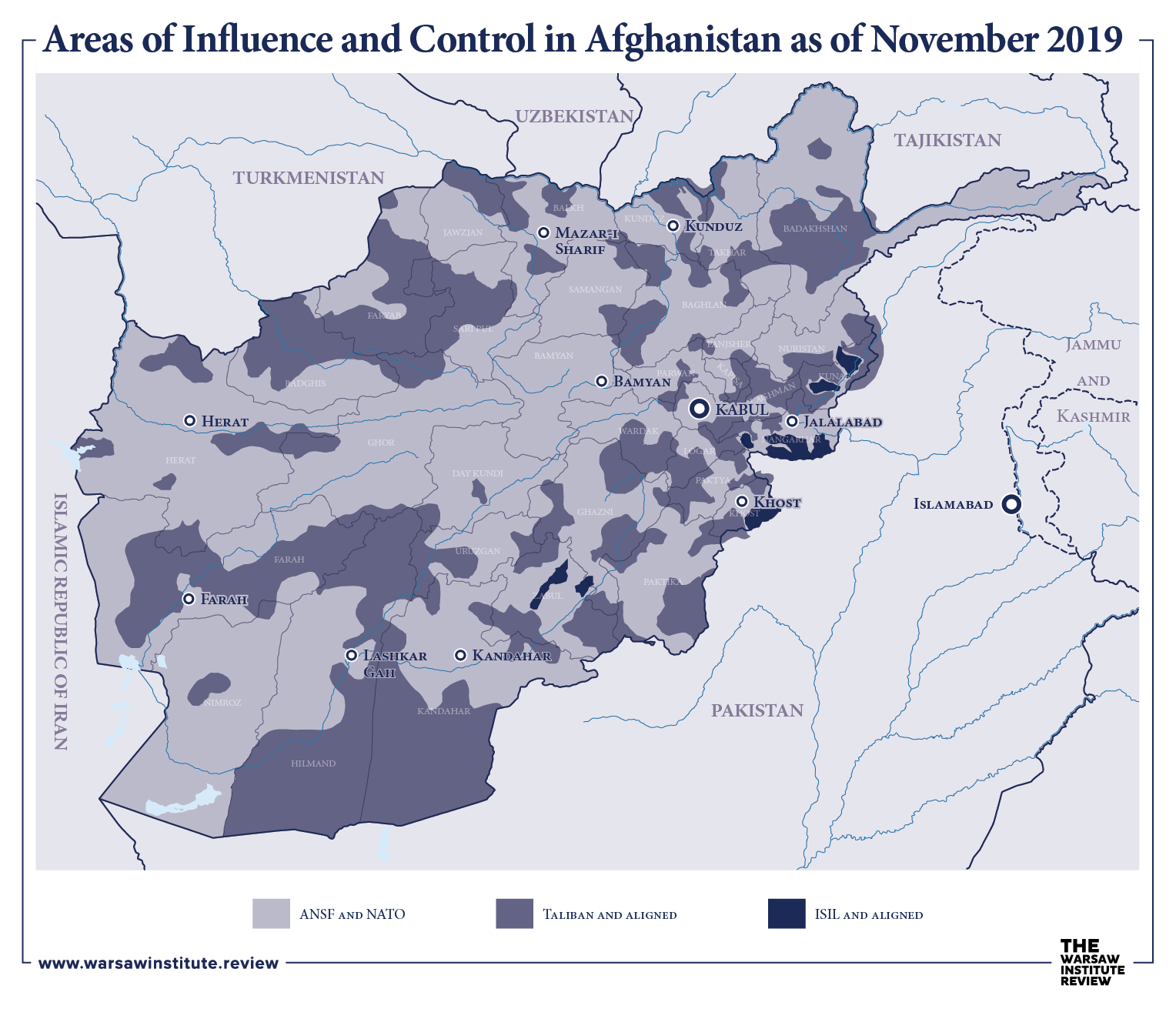

Most notably, the most risky appeal was President Ashraf Ghani even openly stating the idea that the Taliban can transform from an insurgency group into a political movement. Paradoxically, for this to be accepted by the Afghan society, many of their day-to-day conduct must cease (which includes egregious human rights abuses, by the way) which gave them the negotiating leverage in the first place by not being vanquished militarily in the field. At some point perhaps even around this time , the Taliban had slowly managed to regain control of more territory of Afghanistan than any time since their unseating. It is also worth noting that by the end of 2016, the US had only 8,400 troops in Afghanistan. It was still higher than the planned withdrawal. In effect, it was a beginning of a reversal.

In 2017, the US announced a revised strategy for their efforts in Afghanistan, which included refocusing their efforts on more densely populated cities. Sadly, this second turning point which entailed ceding the remote country side to the Taliban and other insurgents meant that their operatives had unhindered time and places there to regroup, and at times and places of their choosing, to infiltrate those very cities, conducting attacks on civilian, political, and military targets.

Hence, at this time and the beginning of 2018, there was another, more shocking surge in violence across Afghanistan. Civilians protested decisively and loudly across several cities, completely fed up with the misery and bloodshed. The reminder is that both the Afghan government and the Taliban react to the appeal of the civilian population, though, the Taliban generally do so by terrorising those they are unable to persuade.

Therefore, it was a welcome surprise when, in June 2018, there was an announcement from President Ashraf Ghani for an entirely unprecedented, nation-wide 3-day ceasefire, between the Afghan government and the Taliban for Eid celebrations. Just as there was a glimmer of hope, added by the Afghan government extending the ceasefire unilaterally, another suicide bombing ruined those celebrations . It is worth noting, the Taliban was internally divided still about the ceasefire, some keen and others adamantly against. This bomb was denied by the Taliban, and may be likely the work of the ISIL faction aiming to disrupt peace efforts. Or, that of the Taliban members against the peace efforts, skilfully blaming their rival insurgents.

Though the Taliban resumed fighting and their preconditions remained i.e. all foreign forces are to be expelled, etc., it did nonetheless construe a significant, albeit symbolic, third turning point indicating that through mass civilian pressure and encouragement, it is possible.

In July 2018, low-key negotiations between the US and the Taliban at the political office in Doha began without the Afghan government. In October 2018, these expanded formally with US Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad, and began a series of rounds. In these, there are 4 main elements:

1. a guarantee is needed from the Taliban to prevent armed groups use Afghanistan as a base to attack externally, which would in effect demand a disavowal of al-Qaeda;

2. an entire withdrawal of NATO forces from Afghanistan;

3. dialogue between the Afghan government, the Taliban, and other relevant entities;

4. and, most precariously, a permanent ceasefire – and a real end to the violence.

Though a positive development, the fighting continued, and it continues messily. Worse still, a UNAMA report states that in the first half of 2019, pro-NATO and pro-Afghan government forces had been responsible for more civilian deaths than the Taliban and other armed insurgent or terrorist groups, for the first time.

Since those initial talks in July 2018, a total of 9 separate rounds of talks between the US and the Taliban have taken place in Qatar. Yet, as the negotiations and Afghan government consultations were ongoing, in the field, fighting continues. To be clear, this does not mean some sporadic clashes here and there. The Taliban was still launching frontal offensives and suicide bombings across Afghanistan, and NATO forces were responding with ferocious airstrikes and coordinating raids. Negotiating belligerents, therefore, aim to continually elevate their negotiating position by displaying their reach and operational capabilities.

The most recent of the talks in Doha, the 9th round, wrapped up on 01.09.2019. The next day, 02.09.2019, US Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad met with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani to present a draft outline of a peace agreement between the US and the Taliban, culminating from a year of discussions. Albeit just the very same day, i.e. 02.09.2019, a Taliban suicide bombing targeted international organisations and aid agencies in Kabul killing 16 civilians, during a TV interview with US Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad in which he was just saying the peace agreement had been ‘in principle’ tentatively finalised.

A Taliban car bombing on 05.09.2019 within the fortified Shash Darak zone , which includes the US Embassy, killed 10 Afghan civilians, a Romanian soldier and a US service member. Hours later, another attack outside an Afghan military base killed more Afghan civilians. Hence, on that same day, the US cancelled the negotiations and a secret meeting at Camp David. The concept was flawed and premature regardless.

What the mediating parties and US officials which engage with the Taliban core deal with, however, is that the Taliban, like several other insurgent terrorist groups had undergone splits, joints, shifting alliances – all of which substantially dictate their mode of conduct.

Insurgencies Fractured

Shifts in organisational structures of these groups can be attributed, in part, to changes in core leadership, hence the logic of going after leading figures in terrorist groups. The Islamic Jihad Union (IJU) separated from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) in 2002. Differences in regard to the approach of those which split to the IJU from the IMU really only manifested after the death of their leader.

The Haqqani Network the most lethally instigated carried out asymmetric war tactics . As it was designated a terrorist entity by the US in 2012, it seamlessly merged in with the Taliban, further complicating matters. Indeed, using inclusive methods like this, the Taliban was able to coherently overcome ethnic and tribal divisions since its inception. Therefore, when the internal division within the Taliban’s ‘Rahbari Shura’, or Leadership Council, that began to sow, it constituted a vital turning point, but taking advantage of it is neither simple nor obvious.

A partial, though quite real, part of this was caused by the hesitant yet increasing indicators that the US may be willing to negotiate with the Taliban upon its announcement of withdrawal plans. Whilst some Taliban members were enthusiastic about this, others were sternly against even considering the possibility. Early instances of fragmentation entail a separate, supposedly even more radical faction, Mahaz-e Dadullah, led by Mansoor Dadullah, a Kakar Pashtun, which began operating even as early as 2010 as a wing of the Taliban, and beginning to target political figures of the Afghan government. Additionally, another splinter group, Fidai Mahaz, emerged in 2013, from discontented members both Mahaz-e Dadullah and Taliban, dogmatically opposed to negotiations with the US.

Even more straightforwardly impacting the internal Taliban divisions, however, was that in April 2013, Taliban founder Mullah Omar died. It would be kept a closely guarded secret for another two years . Besides some Taliban higher ups, the resentful leaders of both these groups too argue that the new Taliban leader, Akhtar Mansour, was not chosen to succeed and so had killed his predecessor, not tuberculosis as claimed otherwise.

Hence later, in July 2015, when Mullah Omar’s death could no longer be kept hidden, the Taliban’s largest split occurred, and as a direct result, its main splinter emerged; the Islamic Emirate High Council of Afghanistan (IEHCA). The shift also induced a merger , where Mansoor Dadullah, the leader of the Mahaz-e Dadullah faction, became the deputy in IEHCA. Moreover, the Afghan government began to quietly aid the breakaway faction, as it weakened the Taliban core.

This opened a new front against the Taliban, and a sudden increase in violence, during which Mansoor Dadullah and several commanders were killed in November 2015. This infuriated Obaidullah Hunar, another Kakar Pashtun, who had remained on the core Taliban side. He created yet another splinter, the Islamic Movement of Afghanistan (IMA) in February 2016. Though he too was killed shortly after, the IMA remains affiliated to the now weakened IEHCA, having fought against the Haqqani Network members which retained support for Akhtar Mansour.

Complicating matters further, a distinctly additional (third) front has opened against the Taliban as attacks in Afghanistan began to be carried out by the ISIL Khorasan Province (ISIL KP) faction , also in early 2015. Defectors from the Taliban, al-Qaeda as well as from other fractured insurgent groups in the region joined ISIL KP.

The al-Qaeda and ISIL split of August 2013 had eventually caught up to this part of the world too. The IMU, operating in northern Afghanistan since 1998, had now shifted its allegiance from al-Qaeda to ISIL KP. This triggered another internal split , where part of the IMU wished to distance itself from this move and remain allied to Taliban and al-Qaeda instead. In this instance, IJU had pledged allegiance to the Akhtar Mansoor leadership of the Taliban. This may attest to continuity as the preferable alignment in in IJU’s deal-making or ideological calculus.

Hence, the war had now become even more multifaceted, and roughly in time for a pivotal moment as well. Replacing ISAF, the NATO Mission Resolute Support (RS) officially inaugurated in January 2015, whose objectives remained similar, though shifted approach to ‘advise and assist’ the Afghan government and ANA, considerably increasing their share of responsibility for meeting these objectives. US troops in Afghanistan had reduced to 16,100 at this point, and other NATO members are withdrawing.

In May 2016, Akhtar Mansoor was killed in a US drone strike, which initially cancelled potential talks with the US (again), and the Taliban appointed Haibatullah Akhundzada to lead the Taliban. Haibatullah is different than both Omar and Akhtar Mansour. Whilst he is a highly regarded clerical figure, he does not have as much of a strong personality to manage Taliban military hierarchy, nor does he have their hands-on approach. Note: the strongest advocates to appoint Haibatullah as head of Taliban were military commanders from Kandahar, similar areas in which the Haqqani Network is nefariously active. His appointment, therefore, may be to some extent an allegory to sustaining Taliban unity rather than him assuming a concrete leadership role. A situation of an absent leader may be also indicative of which elements internally wield decision-making influence.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

NATO and ANSF operations against ISIL KP intensified in 2017 and they were remarkably effective. As soon a new leader was identified, he was killed . The Taliban strategically accused insurgent opponents as affiliated with ISIL KP, making use of the concentrated efforts of other entities, namely the ANSF and NATO forces, to hunt ISIL KP expansion down. It is worth noting that ISIL KP is significantly different than ISIL in Syria or Iraq.

First Peace Agreement – the curious case of Hekmatyar

Such developments convey shifts in the status quo on the geopolitical chessboard ‘in the field’ in Afghanistan. It is not farfetched reasoning to suggest that among effects these shifts have, they could encourage those to head towards the negotiating table who would have otherwise been previously reluctant, or had insufficient incentive to do so.

Upon the Taliban dominating Afghanistan, and Hekmatyar having lost the support of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and other Mujahideen, he fled to Iran in 1997, with a shared antagonism for the Taliban. Moreover, Hekmatyar was excluded from the formation of the new Afghan government in 2002. He aligned his group’s motives alongside al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and fought against the Afghan government and NATO, and so, that same year Iran expelled him.

In his absence, several of the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin faction’s members had defected to the Taliban and al-Qaeda. Other defectors of the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin faction had a different approach; they joined Hamid Karzai’s administration in the Afghan government, taking up over 30% of government positions even prior to 2004. Intriguingly, Hekmatyar’s intent to remain independent whilst avoiding marginalisation was conveyed in a two-pronged approach, in a way, mirroring the paths of his defectors. Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin faction reminded of its presence with sporadic suicide bombings throughout the course of the conflict, being possibly responsible for a notorious attack on aid workers in August 2010, and attacks on civilians, military and political targets. Yet, on the other hand, the political party wing of Hezb-e Islami, functioning in local politics, also began to take up seats in the Afghan parliament. Also in September 2010, Hezb-e Islami secured 16 out of 249 seats in the Wolesi Jirga elections.

Therefore, for others it could have been difficult to distinguish between those which did indeed defect from Hekmatyar and those which stayed loyal to him, or in a grey area in between. This would make his perceived influence in both government and jihadi circles larger than probably was, which was in turn used to de facto increase his influence, whilst yielding a shadow over his defectors.

It is also not farfetched to assume the interwoven nature of the Hezb-e Islami political party and Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin military faction, regardless of claims otherwise. Around this time, Hezb-e Islami made appeals to negotiate with the Afghan government, reiterating earlier demands for expelling NATO forces, and presenting it as a peace plan, meeting again in 2012 with Karzai. Considering the increased activity of other factions and dominating role played by the Taliban in the anti-government circles, the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin faction was becoming steadily less relevant. Hence, the decision to formally ally with the Afghan government.

As a result of continuity, Ashraf Ghani saw that in September 2016, the first peace agreement was signed since the post-invasion phase of the war, inked between the Afghan government and the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin faction. These would be later backed by the EU in 2017. Of course, the citizens of Kabul who remember the shelling were not too happy about this. Others were just relieved some peace deal had been sealed. It does set a precedent, for what circumstances and incentives can be identified or stretched in pursuit of peace.

What the case of Hekmatyar gives insight to is also the changes since 2002 in the socio-political landscape of Afghanistan. in the backdrop of the war and insurgency, that are rather remarkable.

WIR interview with H.E. Gul Hussain Ahmadi, Ambassador of Afghanistan to Poland

The author of this written piece held an interview with H.E. Gul Hussain Ahmadi, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to the Republic of Poland at the premises of the Embassy in Warsaw on Thursday, 07.11.2019 during a ‘Strategy Duologue’ meeting with The Warsaw Institute Review (WIR), for insights into ways forward.

Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for the purpose of publication. An account of the remainder of the discussion can be found on the WIR website.

WIR: What are the next definite steps needed for the Afghan Peace Process?

Ambassador: The journey to stable and democratic Afghanistan has already begun since 2002, and in this journey there are many achievements. We will continue this political process and development at the best pace we can, we believe the Taliban dialogue can happen, it should happen, though under the leadership of the Afghan government. In the meantime, we will continue all political mechanisms which have already started, parliamentary elections, provincial councils, keep doing our best to strengthen the democratic process.

Source of terrorists should be addressed, and the places they enjoy a safe haven need to be tackled. The ANSF is facing the challenges, international community is supporting, with concrete frameworks right up until 2024, and beyond. Afghanistan is grateful for the international community’s support, and it is important to acknowledge that Afghanistan is front line in the fight against terrorism, in which we have lost thousands of soldiers and our civilians. On top of the Taliban, there are several other terrorist groups, from a surprisingly large number of nationalities. Terrorism is a dangerous threat for the world, and Afghanistan is on the front line.

WIR: What does the international community not understand about Afghanistan?

Ambassador: Mostly, that Afghanistan is an entirely different country than it was even just 10 years ago, let alone since the post-Soviet phase. There is incredible progress in education, with multiple million more education institutions. Higher education institutions have increased, both public and private. In energy, the TAPI Pipeline and the CASA-1000 projects show real cooperation with neighbouring countries, as well as in infrastructure, such as the multinational-funded Highway 1, or the ‘Lapis Lazuli corridor’, also as trade links with neighbouring countries. The civil society is flourishing, with think tanks, many independent and government media and radio outlets, and of course, four complete presidential electoral cycles have take place, with the vote of the most recent elections of 28.09.2019 underway. Whilst imperfect, the pace of progress is really something.

WIR: Should we encourage the US and Taliban representatives to return to the negotiating table in Doha?

Ambassador: Any such meeting is welcome, though as a preparatory step. So, we do encourage the US Envoy. Afghanistan is ready for peace, to accept Taliban for integration in the society in the proper manner for the best of the future of Afghanistan. The first priority for the Afghan government is bringing peace to Afghanistan, and is determined to negotiate with the Taliban, and to bring them back into society. Such meetings can help prepare the ground for the intra-Afghan talks. We believe the peace negotiation should be Afghan led and Afghan owned, as well as inclusive of various political parties, so if we are going for dialogue, we need dialogue not just from government, but also outside the government, as there are many parties that are not in the government.

WIR: How do we separate members of the Taliban who want negotiations, and those who are adamantly against them? Is there an idea for a mechanism to give them a chance to defect safely?

Ambassador: It ought to be underlined that the Taliban are not a unvarying set of people. Its best understand that there are 3 layers. The first is the top leadership, who have an office and base, in Qatar and Pakistan respectively. Second is leadership of commanders in the field, in districts, and rural areas. Finally, the third layer is the people, they are not Taliban largely because of ideological sway, but because they are poor, or just living in an area overwhelmed by the Taliban, and so they take up the guns, and get salary for waging violence and avoid retaliation for saying ‘no’, these people are all young, less than 30 years old. It comes down to manipulation and poverty. We need to deal with leadership, especially if they are receiving support from other countries, pressurise of sources of Taliban. Furthermore, comprehensive disarmament processes were underway from 2002 to 2006 on a nationwide scale, stopped because it was finished with the warlord-era setting. Afghanistan underwent mass disarmament and some individuals were taken to the ANSF, and some went to private sector from resistance groups fighting against Taliban.

Observe Those Observing

The Ambassador’s insight shows us that Afghanistan’s circumstances are becoming more and more characteristic of a country ready to move on from insurgency phase.

Geopolitical developments within Afghanistan and in the South Central Asian region have always been intertwined and observant of one another, very much characteristic of a ‘two-level game theory’ environment. In that, insurgency groups in Afghanistan have frequently and chaotically undergone fragmentation, shifts, and realignments.

Indeed, immediate effects of the US cancelling peace negotiations with the Taliban included an uptick in operational intensity, but also competing states seizing the opportunity to swiftly step in to present themselves as alternative interlocutors, attesting to their perceptions of the status quo and their understanding of the Taliban.

On 09.09.2019, just 4 days after talks were called off, consultations between the Afghan government and the Taliban took place in Iran. Previously, 30.12.2018 Iran had also hosted a Taliban delegation in Tehran. Iran’s foreign policy objective in Afghanistan is to achieve stability , and avoiding confrontation, as indicated by not having attacked US forces there, even in light of tensions in the Persian Gulf. Moreover, Iran does have a history of having recruited Shia militants from Afghan refugees living in Iran, taking advantage of the sectorial dissonance, to fight in Syria as well as in Iraq, often accompanied with promises of potential work permits in Iran.

Russia has made strides to present itself as a more reliable partner than the US, competing for favour across various countries possibly in part in the belief that this would make its claims in contention points elsewhere more valid. As Russia also began avidly hunting ISIL in Syria, and extended their hunt to Afghanistan, too emerged suspicions they did this also by means of supporting the Taliban. After military operations and drills, some equipment would simply be left behind in convenient places. Later on, Russia has also made strides to present itself as an alternative mediating party to the conflict in Afghanistan, attempting to appeal to partners in the Central Asia region. Having inviting the Afghan High Peace Council, separate from the Afghan government, as well as the Taliban, to Moscow in November 2018 and in February 2019, Russia did not hesitate to do so again upon hearing the cancelled talks on 13.09.2019, and received another Taliban delegation visit. What was particularly pertinent in these talks, however, was that Russia conveyed it was in its interest that the peace negotiations go through, and the Taliban declared it was willing and open to returning to negotiations with the US. Russia offered to act as a guarantor for US-Taliban talks on 28.08.2019, just days before they collapsed.

That week, UN Security Council Resolution 2489 renewed UNAMA’s mandate. Yet, at the UN Security Council, China was threatening a veto as the document no longer made references to the Belt and Road Initiative, as some in the past had done. Other Members regarded this as an attempt to exploit a conflict zone to force in a separate pursuit of geopolitical interests. China had previously conducted special military operations in the north-eastern parts of Afghanistan, long the border with China, against ISIL units, and those which would cooperate with militants in Xinjiang.

Qatar has been facilitating these negotiations in Doha, presenting itself as a reliable partner in the MENA region and as a facilitating mediator. This is important for Qatar’s relationship with the US, on top of hosting the Al-Udeid Air Base, as those observing are also the countries which have imposed a blockade on Qatar since 05.06.2017 i.e. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt. Unsurprisingly, some of which have offered themselves as an alternative to Qatar as a mediator in this affair, though thus far without success, and then criticised Qatar’s role in it.

Hence, naturally Iraq is also observing the developments in Afghanistan, as a country that too has a NATO presence in it. Namely, the Hashd a-Shaabi, the dominant pro-Iranian militia, which is comprised of multifarious factions and too are at times internally divided, are watching how the Taliban insurgents in Afghanistan deal with the US, but also vice versa, since they are already legitimised to some degree with their political wings enjoying seats in the Iraqi parliament.

As such, on the other hand, the US can feel the pressure, as its geopolitical rivals as well as its close friends, need to know what the status quo really is. Having acknowledged the time has come for NATO to depart, and having agreed that the withdrawal cannot be too rapid or reckless as it would compromise the limited achievements already secured.

Pakistan has attempted to distance itself after 2001 from the Taliban, though the networks to some extent remained, and are changing with avid precariousness. Pakistan is presenting itself as a reliable partner to the US, and as a go-to for communications to encourage the Taliban to the negotiating table with the US. Most especially, after having being criticised of not fighting hard enough against Taliban and affiliated elements, Pakistan does also use its involvement in Afghanistan as a leverage point to bring the US into the Kashmir dispute with India.

India, meanwhile, has been the only state actor in the region to affirmatively deny potential legitimacy to the Taliban. India has also firmly has refuted international mediation in the Kashmir dispute since 1971, maintaining that this is a bilateral issue, and recently, that it is merely an internal issue, and downplaying Pakistan’s card in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s Chance for Peace

A conclusion which can be drawn is that: actors on the international area, that find themselves in a similar situations mimic other actors, adjusting for their specific situations, but learning from their lessons. Just as important, therefore, or perhaps even more important than the actual capability to exert force, is how the projection of power is perceived by other actors, because that is what they will act accordingly to.

Whereas for the attitudes amongst civilians, a Foreign Policy article illustrates that people risk their lives to vote in areas threatened by the Taliban, some understandably refrain, but because of the danger of attack, not all from apathy to the political system. Meanwhile, UNAMA efforts are concentrated on encouraging insurgent fighters to give up their arms, with relatively modest, but very important progress made in part of the Afghan government Peace and Reconciliation Process. It showed that some Taliban members wanted out. It also showed that, certain Taliban members joined because waging violence to earn a living was their only option, and when presented with an alternative, they took the risk.

When a social fabric is re-engineered, it rarely is implemented immediately. The seeds have been planted, for Afghans are beyond tired of war, conflict and violence, and even after the US withdraws, some values elements will remain. Noting that the Taliban will have to win hearts and minds should they seek to continue their pursuit of legitimacy, and to do that they will have to cease their terrorist conduct. Soft power is the underutilised instrument of peace in this scenario. With this, the symbolism of another ceasefire becomes more attainable. Afghan civil society entities are keen to play a better role, advocating for human and women’s rights, as Afghan civilians excluded from these closed-door negotiations, the effects would be suboptimal – this is not to say that, in the midst of resurging violence whilst seeking an exit strategy, this is easy or feasible.

Furthermore, is the factor that the US is to withdraw conventional troops, but funded paramilitary groups, directly reporting to the US and NATO allies, will still operate in Afghanistan. Perhaps even expand. Whether they substitute a larger conventional presence in terms of political or operational objectives may remain to be seen. If the US can show both China and Russia, that it can exit a quagmire which it entered with reason, it can realign priorities, having secured some achievements – this strikes a very different message than one sounding of having been defeated politically, which is not necessarily the case, as some would argue. The other message is that, if the necessary changes have not been achieved, then withdrawal does not happen. The message is therefore, after the US-Australian-Afghan and Taliban agreed prisoner exchange of 20.11.2019, and return to informal negotiations in Doha besides Trump’s Afghanistan 28.11.2019 visit, that real concessions are needed, and they are not as costly as would seem – avoiding them could be more costly to both sides.

At the end of the day, the Ambassador’s elaboration really emphasises how the setting, despite the backdrop of insurgency, is one that is ready for peace, with mechanisms already existing to reintegrate ex-insurgents. The fracturing of the Taliban due to some being intent on negotiations gives momentum to this, as does the example of Hekmatyar, although not everyone was happy with it, factors which attest to peace and hint eventual normalisation are getting better.

Afghanistan’s chance for peace is at hand.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.