SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 1 August 2019 Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

INF Treaty: U.S.-Russian Outdated Pact

The issue of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) Treaty has surged as one of the critical factors in U.S-Russian relations, contributing to their even greater deterioration while exerting a negative impact on Moscow’s future ties with Washington.

• The INF Treaty has outlived its purpose, in both formal and real terms. The pact does not take into account the current state of military confrontation between Russia and the West nor does it include how nuclear weapons have developed worldwide over the past thirty years. It also neglects the fact that a large group of countries that are not covered by the pact has in their nuclear stockpile medium-range missiles. Among such states is China, whose atomic arsenal keeps posing a threat to the United States and its Asian allies.

• While bringing the matter of the INF compliance to a head, Washington felt inspired by two major motives. First, it could no longer give the nod to being the only side to comply with the treaty while the other party, seen as a severe risk to U.S. security, breaches the provisions of the deal by making attempts to construct a forbidden weapon. Secondly, from Washington’s point of view, any mechanism to limit further proliferation of medium-range weapons will make sense only if it embraces China within its framework.

• Although the United States first informed about Russia’s violation of the INF Treaty in 2014, the first signs had appeared as early as in 2007. But before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the Obama administration had not raised any public concerns over breaching the treaty. As reported in late 2016 and early 2017, these missile launchers entered into military service. The U.S. Pentagon said back then that Russia had already formed a few brigade sets of an upgraded version of its Iskander missile systems outfitted with Novator 9M729 medium-range cruise missiles, known by its NATO codename SSC-8. Some of the U.S. allies even confirmed Moscow’s noncompliance with the INF Treaty.

• The INF’s demise has a much greater political undertone rather than any actual impact on altering the strategic situation in its military aspect. Although still in force, the pact has not prevented Russia from posing risks of missile attacks against targets located across Europe. Such a danger arose after Moscow had furnished its Baltic Fleet and Black Sea Fleet vessels with the Kalibr missiles.

• The INF’s failure may be soon followed by that of the New START nuclear disarmament deal after the United States declared no willingness to extend the treaty after February 2012. The collapse of the arms control system does not have any significant impact on the actual balance of power and military potential of the United States and Russia. Moscow has long had medium-range missiles while having made efforts to develop new types of its supersonic weaponry independently of the INF Treaty.

Launching a missile from an Iskander-M launcher. Source: MIL.RU

Launching a missile from an Iskander-M launcher. Source: MIL.RUThe INF Treaty In 1976, the Soviet Union started fielding a new intermediate-range missile complex called the RSD-10 Pioneer (given the reporting name SS-20 Saber by NATO). In his January 1977 speech delivered in Tula, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid Brezhnev said it would be absurd and unfounded to believe that the Soviet Union was striving for strategic superiority over the West. What he said accelerated a few months later the process of deploying two new missiles to military units per week. A total number of 650 Pioneers were then dispatched, U.S. sources reported. Fielding SS-20 medium-range ballistic missiles raised Europe’s concerns over upsetting a military balance between the two blocs. In December 1979, NATO decided to respond to Soviet deployments of the SS-20 by fielding in Europe U.S.-made medium-range ballistic missiles in a step that coincided with Washington’s talks with Moscow to set boundaries for the possession of such kinds of weapons. Under the Alliance’s decision, 464 Tomahawk ground-launched cruises missiles and 108 upgraded Pershing-2 missiles were installed in European NATO allies. But any attempts to convince Moscow to set nuclear boundaries were doomed to fail. U.S. President Ronald Reagan proposed his Zero Option plan, offering not to proceed with the deployment of Pershing and Tomahawk missiles if the Soviet Union removes its SS-20s. The Soviets rejected Reagan’s proposal and continued to field its SS-20s in Europe while planning to deploy additional short-range missiles, all this despite Brezhnev’s public declarations on “freezing” the Russian missile armaments program. In 1975, there were 567 warheads on intermediate-range missiles deployed to the European part of the Soviet Union and the countries of the Eastern Bloc. By 1983, these missiles ¬– including the SS-20 medium-range ballistic missiles – were loaded with 1,374 warheads in total. Targeted at Western Europe, Soviet-made weapons aimed to intimidate European NATO members and led to a fissure between Europe and the United States. But a tough stance eventually has taken the upper hand in Bonn, Paris and London. UK’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was the first to react while ordering to field 144 U.S.-made Tomahawk cruise missiles on British soil. In 1983, West Germany began deploying Pershing-2 ballistic missiles, selecting the USSR’s SS-20 launch sites as an object of attack. Although Pershing-II missile could not boast of the capacity or range comparable to these of Pioneer, it surpassed its Soviet-made rival in terms of accuracy. This posed risks to the Soviet underground command centers, Moscow worried, though the United States had long warned it could dispatch its missiles. Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov said at the Politburo meeting that a Pershing-2 rocket is capable of reaching Moscow in as little as six minutes, giving the Soviet leadership no chance to hide in fallout shelters. Soviet KGB officers said NATO might brace for a surprise nuclear missile attack on the USSR . In response to Reagan’s Pershings, the Kremlin deployed its latest short-range missile, the OTR-23 Oka (SS-23 Spider), to Eastern Europe. After the first batches of Pershing arrived in the United Kingdom and West Germany in 1983, the Soviets suspended further negotiations. The following two years saw a period of tensions running high between the Eastern bloc and the West, with the risk of the outbreak of the greatest nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis. When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, and the Soviet Union’s economic situation deteriorated dramatically, preventing the country from taking part in a further arms race and deploying its medium-range missiles. U.S.-Russian negotiations came to a standoff due to obstruction from hard-line Soviet generals and marshals. Diplomats who held talks with their U.S. counterparts were barred from conducting further discussions. For instance, Yuli Kvitsinsky, who served as one of the top Soviet negotiators, had never before seen a Pioneer (SS-20) missile. The Soviet military failed to inform foreign ministry officials about many details, a move that led to numerous discrepancies in the number of missiles evoked by the Americans and the Soviets. But U.S. representatives happened to know about Soviet-made weapons more than their Soviet peers, mostly thanks to information handed over by the intelligence service. The talks ended in success, enabling Reagan and Gorbachev to ink the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty on December 8, 1987, in Washington . Reagan’s Zero Option was adopted. The deal banned intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM) and medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBM), with range s between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The INF Treaty prohibited ballistic and ground-launched cruise missiles loaded with either conventional or nuclear warheads. The atomic disarmament deal provided for dismantling all existing arsenals while barring both parties from possessing, producing or flight-testing missiles. [/ctt]The pact forbade producing or possessing missile launchers or bodies but had no reference to warheads. Moscow agreed to dismantle its SS-20 Saber missiles and short-range OTR-23 Oka weapons, even though the range of the latter was much smaller than those stipulated by the treaty.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission. Support

Washington scrapped its Pershing-2 ballistic missiles and BGM-109G cruise missiles. The pillar of the treaty was a strict obligation to control Washington and Moscow to verify whether the two parties to the agreement fulfill their mutual commitments. Both countries managed to dismantle their respective nuclear arsenals a few months before the fall of the Soviet Union. Under the document, on-site inspection activities ended in 2001. The INF Treaty established the Special Verification Commission to act as an implementing body for the treaty aimed at resolving questions of compliance or serving as a platform to file objections. It has met thirty times, with the most recent meetings taking place in November 2016 and December 2017.

Washington, December 8, 1987. Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev sign the INF Treaty. Source: Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

Washington, December 8, 1987. Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev sign the INF Treaty. Source: Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.The Soviet Union destroyed many more of its missiles than the United States did. The INF Treaty did not apply to medium-range weapons deployed at sea or in the air, giving a distinct advantage to Washington. By the early 1990s, the Americans had thousands of Tomahawks fielded on warships and submarines, as well as AGM-86 ALCM cruise missiles on warplanes. The Soviet arsenal seemed much more modest in this respect, though in the 1980s, Moscow established the weapons production like that of America’s Tomahawk cruise missile. Among such rockets were the S-10 sea-launched missiles, the Kh-55 air-launched cruise missiles and the ground-launched KS-122, which were destroyed under the INF Treaty.

It was the first arms control treaty that sought to dismantle ground-to-ground missiles that can be launched to rapidly attack the enemy, giving them no time to react. The INF pact was developed to diminish the risk of war. After the demise of the Soviet Union, the nuclear non-proliferation document encompassed Russia and the United States but Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan, former Soviet republics that had nuclear weapons. These three countries destroyed their atomic arsenal while Yeltsin’s Russia remained committed to observing the treaty. After Vladimir Putin came to power, Moscow began its efforts to rebuild and upgrade its military potential, drawing particular attention to its nuclear missile stockpile. Prohibited tests Moscow started to develop its medium-range missiles in the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, a step that gave rise to Russian violations of the INF Treaty. A ground-launched cruise missile with a range of 500 kilometers, the R-500/9M728, was being created for Iskander missile systems originally armed with ballistic missiles with a similar range. It referred to Moscow’s attempts, initiated back in 2007, to make sea-based cruise missiles Kalibr that is permitted under the treaty easily adaptable to ground-based launchers. Russia launched rockets with a range of over 500 kilometers during an operational test in 2008. Despite being well aware of Moscow’s nuclear attempts, the Obama administration did not hand over information about Russia’s noncompliance with the treaty to the U.S. Senate whose members discussed the ratification of the New START nuclear arms reduction deal. The document entered into force in February 2011 after the reset policy had eventually reached its peak.NEWSLETTER

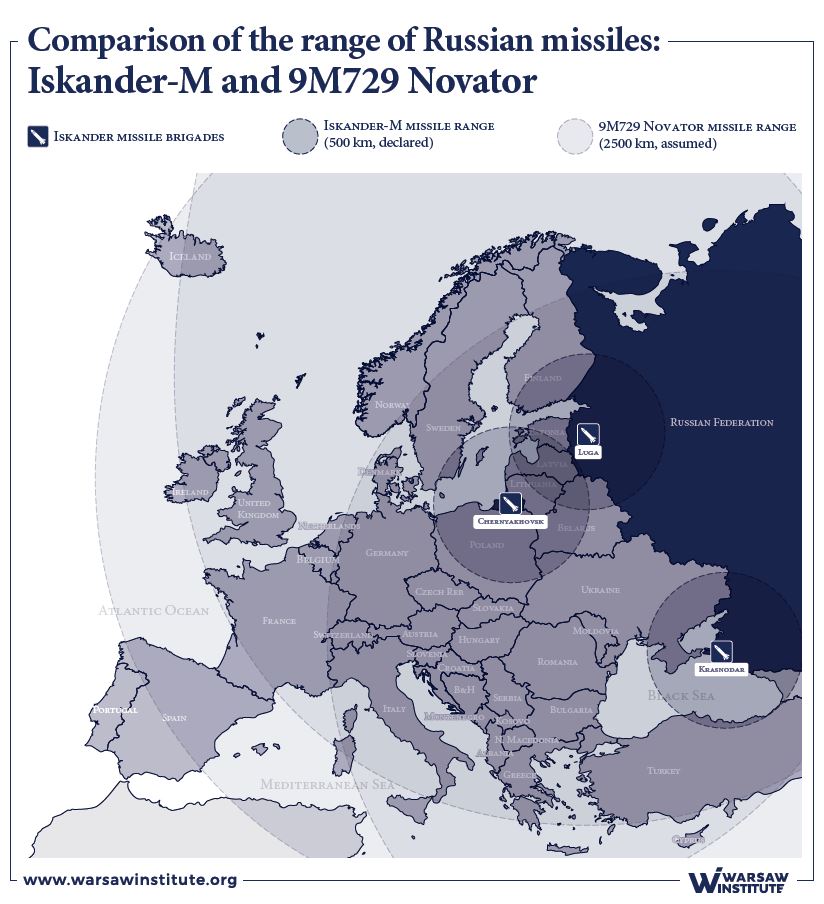

It was not until January 2014 that Washington informed its NATO allies that Russia was working on a missile that went against the INF Treaty. Soon after, Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine and invaded eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region. In a report published in July 2014, the U.S. Department of State stated “the Russian Federation is in violation of its obligations under the INF Treaty not to possess, produce or flight-test a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) with a range capability between 500 and 5,500 kilometers or to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.” No other details, such as the name of the missile, were provided. Military analysts believed to have identified a weapon as the SSC-8 ground-based cruise missile (NATO codename), or the 9M729 weapon, an upgraded version of the 9M728 missile with a range of at least 2,500 kilometers. In 2015, along with long-range sea-launched and air-launched cruise missiles, Russia embarked on production and deployment of the 9М729 ground-based cruise missile. The United States called in November 2016 for setting a special verification commission established under the treaty to deal with compliance issues. But Russia denied its SSC-8s had breached the treaty, and the commission failed to be formed. Testifying in front of the U.S. Congress in March 2017, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Paul J. Selva noted that the treaty-violating system presents a risk to NATO facilities in Europe. In December 2017, the U.S. State Department offered specifics, identifying a 9M729 system as an extended-range version of the Iskander-K, which is a short-range cruise missile. In early March 2018, the U.S. State Department accused Russia on Thursday of developing destabilizing nuclear weapons in violation of its treaty commitments after Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered a speech to the parliament. State Department spokeswoman Heather Nauert said Putin’s remarks showed Russia had breached its liabilities under the nuclear arms reduction pact. “We know our weapons perfectly. We also know that none of them violate our obligations under the treaty,” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said on November 26, 2018, rebuking U.S. accusations of infringing the INF Treaty. Although Ryabkov insisted that Russia did not test its 9M729 missiles that could exceed the range permitted under the pact, the INF Treaty sees as a violation the mere possession of a weapon being able to fly further than such distance. Russian Deputy Foreign Minister stressed that the 9M729 missile, which is an upgraded version of the Iskander-M system missile, was launched at the Kapustin Yar testing ground on September 18, 2017. It was fired at its maximum range and believed to have covered “less than 480 kilometers.” On November 28, 2018, Dutch Foreign and Defense Ministers wrote in a joint letter to the country’s parliament that the Netherlands has obtained evidence of Russia’s violation of the INF pact. “The Netherlands can independently confirm that Russia has developed and is currently introducing a ground-based cruise weapon,” the letter read. This was the first time when a U.S. ally in Europe independently corroborated Washington’s earlier findings. Two days later, Germany’s Der Spiegel magazine wrote that the U.S. administration has intelligence information on the Russian-made missile, including satellite images taken during the missile’s flight as well as information about Russian companies and institutions involved in developing a rocket and a launcher . In his statement published still the same day, Director of National Intelligence (DNI) Dan Coats revealed for the first time much more evidence that the U.S. services collected to prove Russia’s noncompliance with the pact, saying that Moscow developed a flight test program consisting of tests of the missile from both fixed and mobile launchers. Both of them were at the range capability permitted under the treaty. “By putting the two types of tests together, Russia was able to develop a missile that flies to the intermediate ranges prohibited by the INF Treaty,” Coats said. Novator enters military service Russia’s entering the Novator 9M729 missile into military service took place – and still does – among a wide-ranging disinformation campaign. Facing such overwhelming evidence, Russia has only recently decided to change its narrative , officially admitting that it is carrying out work on a 9M729 cruise missile yet denying that the weapon breaks the INF provisions. “We have never denied that work is underway to improve our nuclear missile arsenal. But the problem is that a 9M729 missile has never been tested at a range prohibited by the pact,” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said. A similar, lighter 9M728 with a range limited to 500 km – and permitted under the treaty – was already mentioned much earlier, which allowed at least in part to conceal the possession of “forbidden” missiles from the public. On January 23, 2019, the Russian Defense Ministry demonstrated to foreign military attaches and Russian and foreign media a missile that it called 9M729. The commander of Russia’s Missile and Artillery Forces, Lieutenant-General Mikhail Matveyevsky told that a 9M729 missile is furnished with a higher nuclear warhead and a better guidance system than the previous 9M728 weapon. He also said that the maximum flight range of the 9M729 equals 480 kilometers while arguing that the missile is supplied with fuel only in factory conditions, which prevents Russian troops from boosting its range by refuelling it at a military unit. The existing one provides “the maximum flight range as stipulated under the INF Treaty.” Russia claims that the 9M729 missile is part of the Iskander-M missile system and, like its less upgraded version 9M728, can be fired from modified launch platforms on wheels that typically serve to launch short-range ballistic missiles. How did Russia enter into possession of the upgraded version of the missile? Russia’s plan to “put two types of tests together,” as informed by Dan Coats, which permitted Moscow to work around the ban under the INF pact, referred to two variants of the missile. That missile, 9M728, was tested at least six times from a fixed site, with the longest test seeing the missile fly to a range of 2,070 km . The missile is very close to the Kalibr SLCM – it was developed by the same NPO Novator design bureau, hence its name 9M729 Novator. In the next stage, Russia tested the second version of its 9M729 missiles, both from the mobile launchers and within range limits stipulated by the INF Treaty.

Iskander-M launcher tested during military drills. Source: MIL.RU

Iskander-M launcher tested during military drills. Source: MIL.RUThe Russian 9M729 (SSC-8) ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) is likely to be a ground-based version of the 3M-54 Kalibr missile, known under its NATO name of SS-N-27 Sizzler. It was initially designated in U.S. reports as the SSC-X-8, but officials removed the “X” when it transitioned from an experimental to operational weapon. The Novator 9M729 is a ground-launched supersonic cruise missile, approximately 6-8 meters in length and 0.5 meter in diameter. The missile is 53 centimeters longer than the 9M728 and may carry up to 100 liters more, which may result from an increased volume of its fuel tank. With an upgraded engine, a missile may exceed 500 kilometers in range thanks to extra fuel supplies. The weapon’s maximum range limit is between 2,300 and 2,500 kilometers, depending on which type of warhead it carries. The 9M729 missile may be furnished with either conventional or nuclear warheads. The new launcher Iskander-M loads four missiles; the Iskander launches two. Contrary to what Russia officially claimed, the Russian army had received the 9M729s long time before. But verifying missile deployment sites is a tough task, not only by the fact that this information is highly classified. A satellite image revealed the close similarity of the upgraded Iskander mobile launchers armed with 9M729 to classic Iskander mobile launchers equipped with short-range ballistic missiles. Russian 9M729 missiles were first reported to have entered into military service in early 2017. In February 2017, New York Times quoted a source in the U.S. administration as saying that Russia had secretly deployed two battalions of the prohibited cruise missile at Russia’s leading missile test site at Kapustin Yar in the southwestern part of the country. But back in December 2016, one battalion was believed to have been shifted to an operational base elsewhere in the country, to the Kamyshlov testing site, as it later turned out . U.S. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats said in late November 2018 that Russia has “fielded multiple battalions of 9M729 missiles, which pose a direct conventional and nuclear threat against most of Europe and parts of Asia.” Quoted by the Western press as saying in February 2019, anonymous intelligence officers said that two more battalions were deployed in addition to what had been fielded back at the beginning of 2017, one in Mozdok in North Ossetia and one in Shuya near Moscow . Germany’s Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung newspaper said on February 10, 2019, that Russia had deployed its controversial 9M729 cruise missile at more locations than previously thought. Citing an unidentified Western intelligence source, the German daily wrote that the SSC-8 missiles were deployed to as many as four battalions. In addition to a training battalion stationed at the rocket-testing development site in Kapustin Yar (Astrakhan Oblast), there were three more missile battalions in Kamyshlov, east of Yekaterinburg, in Mozdok in North Ossetia and Shuya, close to Moscow. If to assume that this is true, it would mean that Russia has at least 64 9M729 missiles, with each battalion consisting of four launchers, with four weapons each. What may seem dubious is where the SSC-8 battalions were dislocated. To cover the target areas, missiles should be stationed in the close vicinity of the Russian border. If to believe in what Moscow said about supplying weapons with fuel in factory conditions, this would mean that Russian-made 9M729 cruise missiles are not fit for long-distance road or rail transport. Also, they should be no more than 150 kilometers from repair and maintenance bases with a stockpile of tactical nuclear weapons. Neither Shuya nor Mozdok meets these criteria . The same is true of the missile brigades in Molkino (Krasnodar Krai), Kursk (Kursk Oblast), Totskoye (Chelyabinsk Oblast), Yelansky (Sverdlovsk Oblast), Ulan-Ude (Republic of Buryatia) and Birobidzhan (Jewish Autonomous Oblast). More missiles are likely to be fielded in Luga (Leningrad Oblast) or Ussuriysk (Primorsky Krai). Apart from Luga and Ussuriysk, 9M729 long-range ground-based cruise missiles could theoretically be deployed in Chernyakhovsk (Kaliningrad Oblast) or Gorny (Zabaykalsky Krai). So Chinese and Mongolian territories could be within range, which makes this location highly improbable. Moscow would not seek Beijing’s sharp reaction, given that Russia is hoping to form a lasting alliance with China. It is also doubtful to field one of the battalions in the Ural, far away from potential targets. Using the maximum range capability of the 9M729 cruise missile is possible once weapons are dislocated close to the west to cover most of Europe’s territory. U.S. ultimatum The 1987 deal has surged as a landmark point in U.S.-Russian relations under Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin in 2018. This stemmed from Washington’s mounting irritation to Moscow’s constant noncompliance with the treaty as well as the lack of response to the U.S. calls for observing the pact. Interestingly, Moscow insisted on rebuilding its ties with the United States. Not incidentally, while commenting on intelligence reports on Russia’s developing banned medium-range missiles, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis referred to Russia’s behavior as “double-faced.” Un the autumn of 2018, after many years of diplomatic efforts and threats, Washington decided to terminate the INF Treaty. On October 20, 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that his country will end the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty if Moscow does not comply with the agreement. Trump accused Russia of having violated the pact “for many years” and declared that Washington would develop its weapons if Russia and China do not cease to do so. The British newspaper Guardian reported on the same day that an influential security advisor to the U.S. President John Bolton was pushing for the United States to withdraw from a Cold War-era arms control treaty but faced opposition from within the U.S. Department of State, the Pentagon and U.S. allies. Washington was reported to have briefed its European partners about Bolton’s proposal to sound their reactions, the British daily wrote in the article. What it heard must have been satisfactory because Trump publicly threatened with the U.S. pullout of the treaty, a document that for over the past three decades had been eyed by Europe as one of the pillars of security. President Donald Trump said on October 22, 2018, that Washington will build up its nuclear arsenal, adding that his remark aims to put pressure on Russia and China. And Moscow must have had a closer look at what Trump had said, given that his words coincided with Bolton’s two-day trip to the Russian capital. The issue of the INF pact dominated bilateral talks than took place shortly after Pentagon Chief James Mattis and his Russian counterpart Shoigu met in Singapore on October 20, 2018. U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton spent “nearly five hours” in talks with Russian Security Council chief Nikolai Patrushev. The U.S. top official held later a series of meetings with Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Presidential Aide Yuri Ushakov. Bolton’s visit culminated with a 90-minute session in the Kremlin with Vladimir Putin. During his two-day stay in Russia, Bolton met with several Russian senior officials, informing them about Trump’s stance on the INF Treaty. Although the U.S. security advisor had not handed in a formal withdrawal note, he made it clear that Washington had made a definite decision. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that the Kremlin evaluated that “the U.S. side has made a decision and will soon formalize its process of quitting the agreement.” After Bolton’s visit to Moscow, Russian media outlets and political commentators said that Russia and the United States had come back to their Cold War-era deterrence policy. Russian Deputy Foreign Minister said in an interview for Financial Times that Moscow’s relations with the West fell to the worst point since the Cold War. For his part, Vladimir Putin declared on October 24, 2018, that Russia’s response to the U.S. pullout of the treaty would be quick and effective, mainly by developing new medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles.

Moscow, October 2018. U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton holds talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Source: KREMLIN.RU

Moscow, October 2018. U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton holds talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Source: KREMLIN.RUIt seems that Moscow was right while claiming that Washington is determined to walk away from the INF Treaty, saying this would happen regardless of its actions. November 2018 saw further accusations from the U.S. administration and intelligence services and Russia’s attempts to counterattack by rebuffing Washington’s claims and blaming the United States for breaching the deal. In early December 2018, Washington outlined the situation to its NATO allies. “Russia now has the last chance to come back into compliance with the INF Treaty,” NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said on December 4, 2018, in his remarks. At a Brussels meeting, NATO foreign ministers called on Russia to return to full compliance with the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Their joint statement corroborated the Kremlin’s noncompliance of the nuclear arms control pact, arguing that it is Moscow’s responsibility to maintain within its force. Importantly, all NATO allies adopted a straightforward decision, a step that must have disappointed Russia, especially that U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo presented at the Brussels meeting Moscow with an ultimatum, making Russia either again observe the INF nuclear disarmament deal. Russia had 60 days to comply, or else the United States would start withdrawing from the agreement. In an official statement released on December 4, 2018, the U.S. administration said there is evidence that “since 2013 Russia had developed its 9M729 program, with more than 30 engagements at all levels of the Russian government.” Russia has repeatedly changed its cover story regarding its violating missile. For more than four years, “Russia denied the existence of the rocket and provided no information about it, despite the U.S. provision to Russia of the location of the tests and the names of the companies involved in the development and production of the missile. Russia only admitted that the missile existed after we publicly announced the missile system’s Russian designator but claimed that the missile was incapable of ranges beyond 500 kilometers and, therefore, INF Treaty-compliant,” the statement reads. Washington said it had convened five meetings of the parties’ technical experts to discuss Russia’s INF Treaty violation since 2014. At each of these meetings, the United States pressed Russia on its violating missile and urged it to come back into compliance. These actions were met with denial, though. Russian threats Moscow’s response was swift and sharp. On December 5, 2018, President Vladimir Putin warned that Russia will develop missiles banned under a Cold War agreement if the United States exits the pact. This was a declaration to the Russian public opinion and the worldwide community, giving rise to the Kremlin-made narrative, under which Trump was to be blamed for the INF’s demise. Moscow’s step coincided with its aim to intimidate Europe, eyed as the second pillar of its information strategy. Russia will target countries hosting U.S. missiles if Washington goes ahead with plans to pull out of a landmark Cold War arms treaty, General Staff chief Valery Gerasimov said on December 5, 2018. Gerasimov, who told a briefing for foreign military attaches, said that he seeks to hand them over to his superiors and that if “the INF Treaty is annihilated, this would not remain without Russia’s response.” A reply from Washington came the next day. On December 6, 2018. U.S. Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Andrea Thompson said Russia must destroy its 9M729 missile systems along with their launchers or reduce their range capabilities. In his remarks delivered on December 7, 2018, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov denied that Russia “had violated its obligations under the INF Treaty,” adding that Moscow remains committed to sticking to its commitment. U.S.-Russian statements, demands, and threats made it clear that the Pompeo ultimatum failed to change anything. After 60-day grace period had passed on February 1, 2019, the U.S. administration confirmed its plans to quit the Cold War-era deal, with an adequate decision expected to enter into force on August 2, 2019, after the six-month window, as formally agreed under the treaty. Russia’s response came on February 2, 2019, making Moscow officially pull out of the deal on August 3, 2019. In a live broadcast meeting with Shoigu and Lavrov in the Kremlin on February 2, 2019, Putin announced the suspension of Russia’s participation in the INF Treaty, saying that Moscow will not deploy intermediate-range or short-range weapons to Europe or elsewhere until U.S. weapons of this kind are deployed to the corresponding regions of the world. This was a lie, given the Moscow’s earlier consent to make the 9M729 missiles enter combat service. Russian Foreign Ministry informed on March 19, 2019, that Moscow is pushed for preparing for a potential U.S. deployment of brand-new medium-range missiles while rebuking claims that Russian activities pose a threat in the missile sphere.

Moscow, February 2, 2019. Vladimir Putin holds a working meeting with Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu. Source: KREMLIN.RU

Moscow, February 2, 2019. Vladimir Putin holds a working meeting with Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu. Source: KREMLIN.RUOn June 19, 2019, the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament, adopted a law on suspending the country’s participation in the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty. Earlier, Vladimir Putin had signed a decree on suspending Moscow’s obligation under the pact. Addressing Russian lawmakers on June 24, 2019, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said that the U.S. deployment of land-based missile systems near Russia’s borders could lead to a stand-off comparable to the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. “Representatives of the U.S. administration and the Pentagon (…) keep saying that the United States and the North Atlantic Alliance have no plans or intentions to deploy missiles systems with such range capabilities on European soil. But what is now taking place with the NATO-Russia Founding Act, in which it was stated that the Alliance has no plans, intentions or reasons to field troops close to the Russian borders, in the territory of new states, shows that this is volatile”, Ryabkov said. On July 3, 2019, Vladimir Putin signed a new law on suspending Moscow’s participation in the INF Treaty. Russia, for its part, cited Washington’s decision to pull out of the agreement. Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova said on July 4, 2019, that in a big goodwill gesture, Moscow will not deploy its ground-launched intermediate- and shorter-range missiles, “until Washington deploys missiles of the same class in the designated regions.” In the further part of her comments, she assessed that “no concrete proof” of Russia’s violation of the treaty had so far been delivered, adding that Moscow “did everything” it could “to save the INF Treaty.” The NATO-Russia meeting was convened the next day, serving as a platform for discussing the Treaty on the Elimination of Their Intermediate-Range and Shorter-Range Missiles. Speaking after the summit, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said he did not hear anything of Russia being willing to come back into compliance. Russia’s representative at NATO informed that Moscow rebuked the Council’s accusations of terminating the pact. In its official statement released following the NATO-Russia Council meeting, Russian representatives wrote that Moscow has no intention to place “relevant weapons in Europe and other regions as long as there are no U.S. missiles of short and medium-range there.” Russia called on NATO allies to submit similar declarations. On July 15, 2019, NATO Secretary General made an appeal to Russia to preserve the INF Treaty as a cornerstone of the European security system. But both Brussels and Washington are aware of the demise of the deal, knowing that a new action plan needs to be drafted to get everyone ready for Europe’s new strategic reality. (Still?) United West

Źródło: WARSAW INSTITUTE

Źródło: WARSAW INSTITUTEAlthough Trump’s October statement was a surprise to the U.S. allies in Europe, it needs to be stressed that the American leader sought his response to Russia’s activities to be developed jointly with NATO and its allies. Since 2017, Washington has made efforts to work out a common solution, also by presenting in the summer of 2017 a non-paper that contained plausible proposals. They all intended to boost the ability of NATO’s Western European states to defend their territories against Russian missile systems, by bolstering their anti-aircraft defense or early warning systems, and to deter Russia, mainly by introducing enhanced rotating activity of U.S. B-2 and B-52 bomber jets in Europe and suggested including China and Russia in the INF Treaty. NATO allies conducted long-lasting negotiations at the initiative of the Obama administration. The issue was part of the official agenda of the July 2018 NATO summit in Brussels when leaders voiced their concern over Moscow’s further steps. Russia’s withdrawal from the pact was one of the crucial matters discussed at the NATO defense ministers meeting in October 2018. On October 2, 2018, in Brussels, U.S. Ambassador to NATO Kay Bailey Hutchison told reporters that at present, Russia must halt its development of a banned cruise missile system, furnished with missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads, or the United States will seek to destroy it before it is ready to be fielded. If the 9M729 missile system becomes operational, she warned, the United States “would be looking at the capability to take out a missile that could hit America or any of our allied countries in Europe.” Donald Trump’s tough stance on the INF Treaty was welcomed by most of the U.S. European allies. On October 21, 2018, UK Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson accused Russia of breaking the agreement, saying Moscow had made a “mockery” of the INF. In an interview for Financial Times, he said that the United Kingdom will “stand resolute behind the United States” in pointing out that “Russia must comply with what it had signed.” On October 22, 2018, the U.S. stance was backed by the most important country of NATO’s eastern flank. While in Brussels, Poland’s Foreign Minister Jacek Czaputowicz said that Warsaw “understands Washington’s actions taken to withdraw from its agreement with Russia on eliminating medium-range and intermediate-range nuclear missiles.” He argued that terminating the pact will not lower Poland’s security because Russia, which has already violated the agreement, is a threat to the country, and not the United States. NATO’s spokeswoman Oana Lungescu stated that “in the absence of any credible answer from Russia on this new missile, allies believe that the most plausible assessment would be that Russia is in violation of the INF Treaty.”  Brussels, December 4, 2018. Press conference of NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg after a NATO foreign ministers meeting. Source: NATO.INT In a statement on the INF Treaty issued on December 4, 2018, NATO foreign ministers declared that Russia had violated the 1987 deal by developing and making operational its missile systems furnished with 9M729 cruise missiles with a range capability of up to 2,500 kilometers . For Washington, drafting a joint statement within NATO structures was a successful milestone. Given that part of NATO allies, with Germany at the helm, felt reluctant about escalating relations with Russia in the area of activity that posed a direct threat to Europe, data delivered by U.S. intelligence services must have deemed compelling. But some European countries, including the Netherlands, managed to get information independently of the U.S. ally. Washington made its best efforts to convince its allies to acknowledge Trump’s decision on the U.S. pullout out the INF pact. Notwithstanding that, Berlin and Paris voiced concern about the U.S. plans. The German government regrets the U.S. plan to withdraw from the U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control deal, German government spokesman Steffen Seibert said on October 22, 2018. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, for his part, said that “American frustration is not unfounded,” however adding that “this should not lead to spilling the baby out with the bathwater” and “would be a big mistake.” Maas said Berlin would continue all its diplomatic efforts to prevent the INF disarmament agreement from being unilaterally terminated by the United States. Trump’s declaration came under criticism from French media outlets. Washington’s plan to pull out of the pact was seen as the president’s yet another deviation from international commitments and multilateral approaches. Accusations against Russia of breaking the deal’s provisions seemed to have passed unnoticed, either, with Moscow’s stance being widely discussed while neglecting Washington’s arguments. Most French dailies reprinted the words of an unidentified Russian foreign ministry official who was originally quoted as saying by AFP news agency that “the Americans desire to be the exclusive masters of the world.” France’s leftist Le Monde newspaper gave its nod to a Russian statement saying that Washington’s decision is a part of “the U.S. policy of pulling out of international legal agreements.” Regardless of what objections may be filed by France or Germany, NATO as a whole organism reacted adequately to all threats posed by the end of the INF Treaty. In late June 2019, Stoltenberg said that the Alliance is now considered the possibility to deploy new defense systems targeted at Russian-made medium-range missiles . NATO countries have already discussed plausible retaliatory measures against Russia, making it one of the top stories of the NATO defense ministers meeting at the turn of June and July 2019. The Alliance is soon expected to witness a rift between those who will take two distinct stances. A group of some Western states, among which are Germany, France and several more countries, will opt for a conservative strategy that will comprise both diplomatic efforts and the development of a response to the threat from Russian-made medium-range missiles and anti-aircraft defense missiles. Berlin and Paris are unlikely to accept U.S. medium-range cruise missiles to be deployed on European soil. Some U.S. allies, especially those who feel most intimidated by Russia, permitted this scenario, along with the increase in the arsenal of ship-launched and aircraft-launched medium-range cruise missiles. The United States has already launched a program for developing new medium-range missiles. In the autumn of 2018, the Pentagon began awarding contracts to a number of companies from the United States and elsewhere. The list of the Pentagon’s contractors included Raytheon ($536.8 million), Lockheed Martin ($267.6 million), Boeing ($244.7 million), BAE Systems ($47.4 million) and Thales ($16.2 million). In March 2019, the Pentagon confirmed its plan to create new ground-launched cruise missiles . But the United States may take two or three more years to build, produce and dislocate its cutting-edge weapons. Developing U.S. medium-range missiles will depend on whether they can be used, or fielded in all places where this would make sense, either in Europe or Asia. If U.S. allies refuse to host missiles on their territory, the U.S. Congress may no longer bankroll their production. Back on November 29, 2018, a group of Democratic senators released a draft bill that stipulated for preventing the medium-range missile program from being financed until the administration successfully meets some conditions, also by indicating where such weapons should be fielded. It remains obscure whether U.S.-made medium-range missiles would be dispatched in Europe. To Russia’s satisfaction, the majority of European NATO states, with Germany at the helm, do not want any more weapons to be fielded on their soil, fearing Moscow’s threats to target its missiles at any states that would install U.S. weapons. But some states of NATO’s eastern flank, see this matter differently, being eager, such as Poland, to host U.S. medium-range missiles within the framework of U.S.-Polish military cooperation. Russian goals The Kremlin has been willing to quit the INF Treaty since 2007, that is when work on developing medium-range cruise missiles first kicked off. In June 2013, such was the opinion of Russia’s former defense minister and Kremlin chief of staff Sergei Ivanov. Moscow’s top political and military officials never welcomed the constraints of the deal. Both Putin and Russian generals publicly slammed the pact for being unfair and unequal, almost traitorous, because it forced the Soviet Union to scrap twice as many missiles as compared to those of the United States in the 1980s. This, however, stemmed from the fact that the USSR had boasted about a better-developed component of its nuclear forces. Pro-government media outlets referred to the 1987 pact as forced upon Moscow by the United States and much more favorable for Washington. In February 2007, Yuri Baluyevsky, chief of Russia’s General Staff, openly declared Moscow’s intention to quit the Cold War-era deal. Putin was quoted as saying in October 2007 that “it will be difficult for Russia to keep within the framework of the treaty” in a situation where other countries, especially China, do develop such weapons systems, while the nuclear nonproliferation deal refers to two countries: Russia and the United States. Back in time, Russia promoted the idea of the INF treaty spreading “all over the world,” preparing the ground for its future withdrawal from the pact. Although Moscow did not take action, Putin kept lambasting the deal . Putin began to talk warmly about the INF while praising its role in maintaining strategic stability after Donald Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement. Under the Russian narrative, which so far rebuffed allegations of having breached the treaty and passed the buck on Washington, the United States was to be blamed for burying the INF Treaty. What is worth being analyzed is that Moscow accused the United States of violating the deal, a classic example of a “putting-the-cart-before-the-horse” strategy, making everyone else think that Washington was the first to have stopped to comply with the pact. On December 5, 2018, Russian Chief of General Staff Valery Gerasimov made allegations against the United States, saying that the Pentagon had used dummy rockets with properties similar to Iranian or Korean mid-range missiles to test its missile-defense interceptors. Another alleged example of Washington’s own INF violation was the use by the Pentagon of long-range attack drones (UCAV). Last but not least, Washington could take advantage of the offensive use of the anti-missile defense system in Romania. This gave rise for increased concern, with Russia claiming that there is a hypothetical possibility of deploying, at the Romanian military base of Deveselu, a battery of SM-3 Aegis Ashore interceptors in silo launchers constructed using standard МK-41 launch tubes, mainly used to launch Tomahawk cruise missiles. The Russian military has been arguing the warhead-less SM-3 interceptors at Deveselu could be secretly replaced by Tomahawks and used in a surprise attack against sensitive targets in Russia, for example Putin’s presidential residence in Sochi.

Brussels, December 4, 2018. Press conference of NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg after a NATO foreign ministers meeting. Source: NATO.INT In a statement on the INF Treaty issued on December 4, 2018, NATO foreign ministers declared that Russia had violated the 1987 deal by developing and making operational its missile systems furnished with 9M729 cruise missiles with a range capability of up to 2,500 kilometers . For Washington, drafting a joint statement within NATO structures was a successful milestone. Given that part of NATO allies, with Germany at the helm, felt reluctant about escalating relations with Russia in the area of activity that posed a direct threat to Europe, data delivered by U.S. intelligence services must have deemed compelling. But some European countries, including the Netherlands, managed to get information independently of the U.S. ally. Washington made its best efforts to convince its allies to acknowledge Trump’s decision on the U.S. pullout out the INF pact. Notwithstanding that, Berlin and Paris voiced concern about the U.S. plans. The German government regrets the U.S. plan to withdraw from the U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control deal, German government spokesman Steffen Seibert said on October 22, 2018. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas, for his part, said that “American frustration is not unfounded,” however adding that “this should not lead to spilling the baby out with the bathwater” and “would be a big mistake.” Maas said Berlin would continue all its diplomatic efforts to prevent the INF disarmament agreement from being unilaterally terminated by the United States. Trump’s declaration came under criticism from French media outlets. Washington’s plan to pull out of the pact was seen as the president’s yet another deviation from international commitments and multilateral approaches. Accusations against Russia of breaking the deal’s provisions seemed to have passed unnoticed, either, with Moscow’s stance being widely discussed while neglecting Washington’s arguments. Most French dailies reprinted the words of an unidentified Russian foreign ministry official who was originally quoted as saying by AFP news agency that “the Americans desire to be the exclusive masters of the world.” France’s leftist Le Monde newspaper gave its nod to a Russian statement saying that Washington’s decision is a part of “the U.S. policy of pulling out of international legal agreements.” Regardless of what objections may be filed by France or Germany, NATO as a whole organism reacted adequately to all threats posed by the end of the INF Treaty. In late June 2019, Stoltenberg said that the Alliance is now considered the possibility to deploy new defense systems targeted at Russian-made medium-range missiles . NATO countries have already discussed plausible retaliatory measures against Russia, making it one of the top stories of the NATO defense ministers meeting at the turn of June and July 2019. The Alliance is soon expected to witness a rift between those who will take two distinct stances. A group of some Western states, among which are Germany, France and several more countries, will opt for a conservative strategy that will comprise both diplomatic efforts and the development of a response to the threat from Russian-made medium-range missiles and anti-aircraft defense missiles. Berlin and Paris are unlikely to accept U.S. medium-range cruise missiles to be deployed on European soil. Some U.S. allies, especially those who feel most intimidated by Russia, permitted this scenario, along with the increase in the arsenal of ship-launched and aircraft-launched medium-range cruise missiles. The United States has already launched a program for developing new medium-range missiles. In the autumn of 2018, the Pentagon began awarding contracts to a number of companies from the United States and elsewhere. The list of the Pentagon’s contractors included Raytheon ($536.8 million), Lockheed Martin ($267.6 million), Boeing ($244.7 million), BAE Systems ($47.4 million) and Thales ($16.2 million). In March 2019, the Pentagon confirmed its plan to create new ground-launched cruise missiles . But the United States may take two or three more years to build, produce and dislocate its cutting-edge weapons. Developing U.S. medium-range missiles will depend on whether they can be used, or fielded in all places where this would make sense, either in Europe or Asia. If U.S. allies refuse to host missiles on their territory, the U.S. Congress may no longer bankroll their production. Back on November 29, 2018, a group of Democratic senators released a draft bill that stipulated for preventing the medium-range missile program from being financed until the administration successfully meets some conditions, also by indicating where such weapons should be fielded. It remains obscure whether U.S.-made medium-range missiles would be dispatched in Europe. To Russia’s satisfaction, the majority of European NATO states, with Germany at the helm, do not want any more weapons to be fielded on their soil, fearing Moscow’s threats to target its missiles at any states that would install U.S. weapons. But some states of NATO’s eastern flank, see this matter differently, being eager, such as Poland, to host U.S. medium-range missiles within the framework of U.S.-Polish military cooperation. Russian goals The Kremlin has been willing to quit the INF Treaty since 2007, that is when work on developing medium-range cruise missiles first kicked off. In June 2013, such was the opinion of Russia’s former defense minister and Kremlin chief of staff Sergei Ivanov. Moscow’s top political and military officials never welcomed the constraints of the deal. Both Putin and Russian generals publicly slammed the pact for being unfair and unequal, almost traitorous, because it forced the Soviet Union to scrap twice as many missiles as compared to those of the United States in the 1980s. This, however, stemmed from the fact that the USSR had boasted about a better-developed component of its nuclear forces. Pro-government media outlets referred to the 1987 pact as forced upon Moscow by the United States and much more favorable for Washington. In February 2007, Yuri Baluyevsky, chief of Russia’s General Staff, openly declared Moscow’s intention to quit the Cold War-era deal. Putin was quoted as saying in October 2007 that “it will be difficult for Russia to keep within the framework of the treaty” in a situation where other countries, especially China, do develop such weapons systems, while the nuclear nonproliferation deal refers to two countries: Russia and the United States. Back in time, Russia promoted the idea of the INF treaty spreading “all over the world,” preparing the ground for its future withdrawal from the pact. Although Moscow did not take action, Putin kept lambasting the deal . Putin began to talk warmly about the INF while praising its role in maintaining strategic stability after Donald Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal from the agreement. Under the Russian narrative, which so far rebuffed allegations of having breached the treaty and passed the buck on Washington, the United States was to be blamed for burying the INF Treaty. What is worth being analyzed is that Moscow accused the United States of violating the deal, a classic example of a “putting-the-cart-before-the-horse” strategy, making everyone else think that Washington was the first to have stopped to comply with the pact. On December 5, 2018, Russian Chief of General Staff Valery Gerasimov made allegations against the United States, saying that the Pentagon had used dummy rockets with properties similar to Iranian or Korean mid-range missiles to test its missile-defense interceptors. Another alleged example of Washington’s own INF violation was the use by the Pentagon of long-range attack drones (UCAV). Last but not least, Washington could take advantage of the offensive use of the anti-missile defense system in Romania. This gave rise for increased concern, with Russia claiming that there is a hypothetical possibility of deploying, at the Romanian military base of Deveselu, a battery of SM-3 Aegis Ashore interceptors in silo launchers constructed using standard МK-41 launch tubes, mainly used to launch Tomahawk cruise missiles. The Russian military has been arguing the warhead-less SM-3 interceptors at Deveselu could be secretly replaced by Tomahawks and used in a surprise attack against sensitive targets in Russia, for example Putin’s presidential residence in Sochi.  Russian short-range ballistic missiles cover with their range most of the countries located at NATO’s eastern flank. Source: MIL.RU According to the U.S. administration, VLS are to be deployed onboard while the INF Treaty provides for ground-based systems. Without any prior tests, Tomahawks cannot be used while installing an anti-missile shield. Russia has not even mentioned such attempts but continues to claim that Washington may break the INF Treaty while swiftly replacing the SM-3 ballistic missile interceptors with Tomahawk cruise missiles in the Aegis Ashore launchers dislocated in Poland and Romania. But this would make no sense, neither military nor technical. U.S. nuclear arsenals have no nuclear-tipped Tomahawks while in order to severely hit Russia, thousands of rockets carrying conventional warheads will have to be fired. In 2012, Barack Obama ordered to swap the last batches of BGM-109A Tomahawk cruise missiles. In October 2018, Russian allegations were commented on by Amy Woolf, a specialist in nuclear weapons policy. In a report for the Congressional Research Service, she wrote that the missile defense Mk-41 system uses some of the same structural components as the sea-based system, but argued that it “lacks the software, fire-control hardware, support equipment, and other infrastructure needed to launch offensive ballistic or cruise missiles such as the Tomahawk .” The very first test launch of the Novator 9M729 missile took place in 2008, coinciding with Putin’s famous speech in Munich that prompted Russian military build-up policy. The Iskander launcher, once modified for the use of medium-range missiles, is far cheaper than a missile cruiser while its maintenance costs little, compared to what costs are generated by warships, submarines or strategic bombers. And it is easier to hide an Iskander-K from the enemy’s eyes that to camouflage a frigate. The low-cost deployment of such launchers will open Russia’s door to strike a blow to U.S. troops, bases and allies in Europe, Asia and the Middle East. Russian generals and the Kremlin’s “party of war” were happy to welcome Trump’s decision to pull out of the INF Treaty as this provided Moscow with an alibi for formally abandoning its commitments under the 1987 nuclear arms control deal. Those in Russia who are in favor of burying the pact say that the United States will not field its medium-range missiles in Europe even after withdrawing from the agreement. This would be equivalent to Moscow’s monopoly on ground-based missiles with range capabilities between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. Referred to as cheap in production and operation, ground-based mobile launchers are likely to hit U.S. bases and allies in Europe and the Middle East, with intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) all being targeted at the United States. This would pave Putin’s way for blackmailing the West, allowing him to negotiate the lifting of sanctions or concessions on such thorny issues as the annexation of Crimea or the war in Donbas. This explains the fact why Russia cares little about U.S. nuclear bombs deployed to Europe and Turkey, or it pays practically no attention to anti-missile shield systems in Romania and Poland. Naturally, these military installations will serve Russian diplomats merely as an argument in a new round of talks. Moscow seeks to revive the discussion on the European security system and its brand-new shape, with Russia reaping considerable benefits at the expense of Washington. Putin intends to take advantage of the expiry of Europe’s security policy deal to ignite rows within the Euro-Atlantic community and the European Union. The Kremlin pushed for intimidating Europe with its cutting-edge weapons while hoping to force Europe to discuss the issue of security yet on Russian terms. On October 24, 2018, Vladimir Putin said Russia would immediately target any European nation that agreed to send U.S. medium-range missiles on their soil. Speaking at a joint press conference with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, Putin said that Russia “will naturally have to respond symmetrically” if these missiles are sent to Europe after the INF Treaty expires. European countries that agree to this, he said, “must realize that they will put their own territory at risk of a retaliatory strike.” Russian information strategy is aimed at shifting full political responsibility for the INF’s demise onto the United States to skilfully ignite tensions in transatlantic bonds. The Kremlin is in the hope of observing disputes over the plausible deployment of U.S. medium-range missiles in Europe. Some European countries, with Germany at the helm, will reluctantly eye NATO’s offensive attack, fearing an arms race and fiercer relations with Moscow. This behavior stands in stark contrast to the attitude adopted by the United States, the United Kingdom and the countries of NATO’s eastern flank. If efforts are made to field U.S. missiles in some NATO countries under bilateral agreements, other members of the Alliance may react sharply, with tensions running high within NATO – to the delight to Russia. Moscow hopes that warmer ties with some of the Western countries will embrace Germany, Italy and France, drawing all the three states into a debate on sealing with Russia a deal being somewhat a European version of the INF pact. To put it bluntly, the Kremlin intends to get concessions from Europe in exchange for the promise of not targeting Russian-made 9M729 missiles and other weapons at the Western part of the Old Continent. And Berlin or Paris may be tempted by a Moscow-made vision of greater independence in foreign policy, which would entangle the EU’s avoidance in the arms race between the United States on the other hand while China and Russia on the other. U.S. goals The U.S. decision to quit the INF deal was inevitable, even despite all image-related costs and political risks stemming from mounting tensions within both Europe and the Euro-Atlantic community. The INF pact limited the U.S. operational capabilities towards Russia and China. U.S. President Donald Trump said that the United States “cannot be the only country in the world unilaterally bound by this treaty, or any other.” Those who chided Trump’s decision say that he did labor to Moscow that, despite blatant evidence of having breached the treaty, may blame Washington for the collapse of the pact. Critics say that the U.S. quitting the agreement will not solidify the U.S. security because the country will not have in the foreseeable future any ground-based ballistic or cruise medium-range missiles to be deployed. While the first accusation can be true, the second one displays imbalances in weapons possessed in favor of Russia as a temporary phenomenon – once U.S. missiles are fielded on European soil. In the long run, Washington will have a greater potential for developing its medium-range missiles than Russia. Although Moscow threatens to deploy its missiles after the INF Treaty expires, it has de facto dispatched nuclear weapons for quite a long time. Washington could no longer accept Russia’s noncompliance with the deal and its plans to develop a certain kind of weapons while the United States stuck to the agreement and did not have such a missile in its arsenal. Following its withdrawal from the INF Treaty, the United States will be able to develop a weapon with a range capability comparable to those of the 9M729 rocket to counter Russian threats. This is likely to restore part of mutual deterrence strategies in Europe. In its February 2018 report titled Nuclear Posture Review, the Pentagon recommended commencing research on the development of the ground-launched intermediate-range and medium-range missile and the sea-based cruise missile furnished with nuclear warheads . The Pentagon is capable of building a brand-new ground-launched medium-range cruise missile within a few months after the U.S. decision to pull out of the INF pact. A provision that gives the green light to such a step is contained in the U.S. Congress the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty Preservation Act of 2017. The Trump administration has already announced plans to upgrade the U.S. strategic arsenal, encompassing the medium-range missiles. The October 2017 report of the Congressional Budget Office forecasted that the program would cost about $1.6 trillion in 30 years. The process of developing U.S. missiles may run on two tracks, with modifying already-existing missiles and building entirely new ones. Fielding U.S. medium-range weapons may pose a greater risk to Russia that a widely criticized anti-missile shield system. Pavel Felgenhauer, an independent Russian military analyst, wrote in the autumn of 2018 that “some NATO members argue that it is now vital to recognize the INF’s demise and to brace for fielding new ultra-precise, intelligent and secretly hidden Euromissiles that could detect and destroy mobile ground targets.” The analyst later said that “this variant presents a threat to Russian silos and mobile intercontinental missiles, much worse than any anti-missile shield to be deployed in the future and, first and foremost, technically possible in a short time.” There may be yet another reason why the U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty might turn sour for Russia. Moscow was keen to combine the matter of medium-range missiles with other disarmament issues, including hoping to limit the anti-missile shield program or extend the New START Treaty. The agreement is set to expire in February 2021 and the United States has not yet decided to renew the pact. Russia, for its part, holds greater interest in extending the deal negotiated and signed by Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev in January 2010 in Prague. Under the agreement, both countries committed themselves to halve the number of their launchers and strategic nuclear warheads. The Kremlin sought to convince the United States to halt or abandon the idea of installing an anti-ballistic missile defense system in Poland and Romania, a similar facility in Japan. Also, Moscow raised the issue of imposing limits on developing U.S. conventional precision weapons while insisting on Washington’s guarantees on outer space demilitarization . When taking an ultimate decision on the INF Treaty, Donald Trump made it clear for Russia that it cannot play one nuclear disarmament pact to reap benefits while negotiating a new deal. A plan to join the INF Treaty and the New Start agreement was part of the agenda at the July 2018 summit in Helsinki.