SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 05 August 2021

Author: Paweł Paszak

U.S.-China Trade War: Origins, Timeline and Consequences

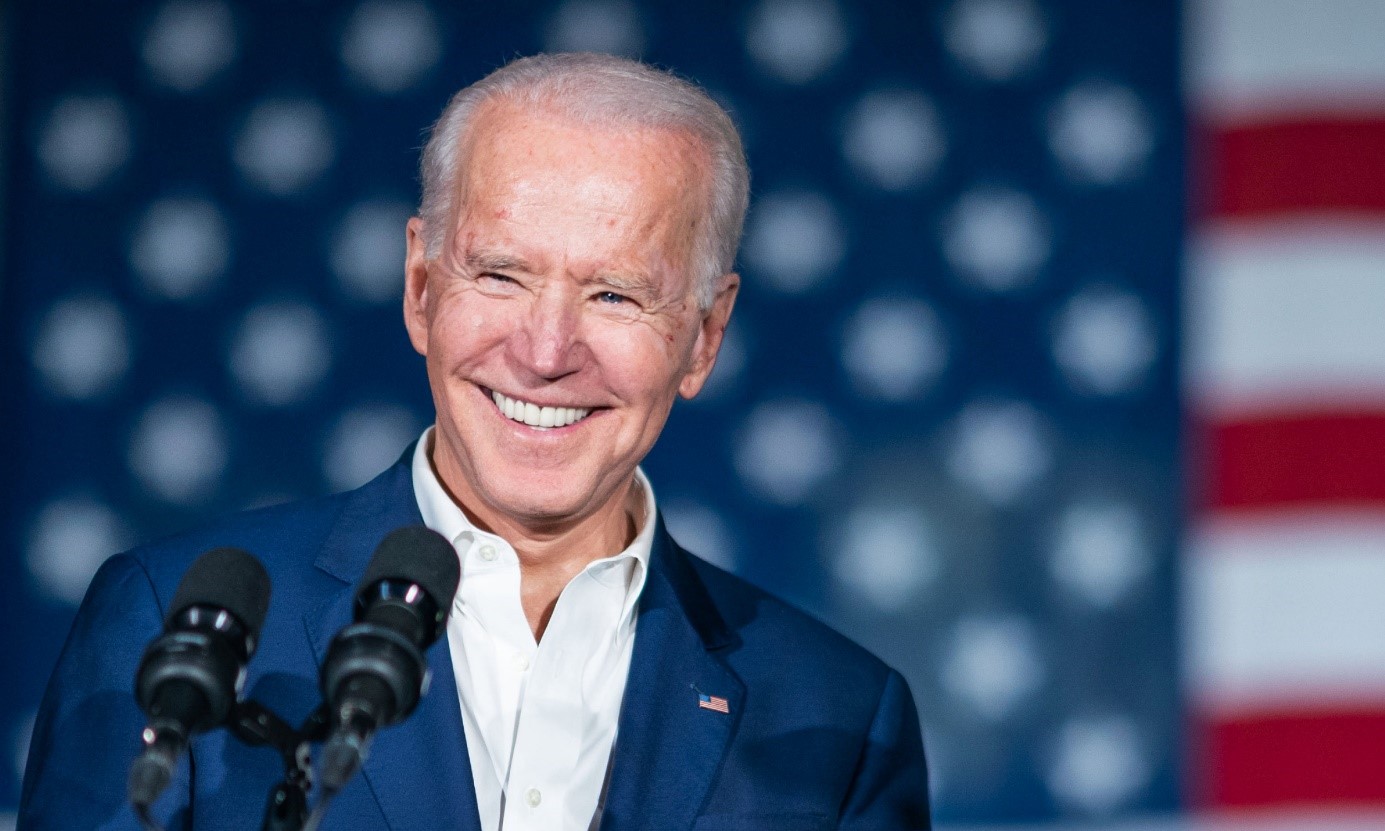

The first version of this report was published in early April 2020, during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic and after the „phase one“ deal was signed. The situation worldwide and U.S.-China ties have both gained momentum since the report was first released, to which added up the intense presidential campaign in the United States and the worsening recession across the globe. The victory of Joe Biden and the end of Donald Trump’s term are both the events that allow for delivering an insight into what took place between April 2020 and January 2021 while testing out some hypotheses suggested a year ago. This paper was supplemented with trade data and some information on to what extent the countries met the target as outlined in the contract. It also features reports on new restrictions on technology transfers as introduced by the U.S. Department of Commerce in May and August 2020.

- The U.S.-China trade war is a tool for the rivalry between two great powers––the United States and China––which is likely to dominate the first half of the 21st century. Washington’s goal was to keep its advantage in top industry and service sectors while offering domestic businesses better protection schemes and more symmetrical access to the Chinese market.

- A firm customs policy is a mechanism for shifting the existing model of globalization and trade worldwide as the latter is less and less beneficial for the United States. The outcome of the U.S.-China economic row will shape America‘s position as a world superpower alongside the U.S-endorsed international order.

- Domestically, the trade war responds to the growing dissatisfaction from some social groups that suffered most from globalization schemes and that exert mounting pressure on state authorities. Not only are bigger customs tariffs and sanctions an attempt to shield material interests, but also to stay in power and manage public mood.

- What the Trump administration did served to lend credence to its slogan Make America Great Again ahead of the presidential election in November 2020. Trump’s 2016 victory came as he managed to exploit public resentment amid wage inequality, rising debts, and job losses. America’s protectionist customs policy had its purpose: to convince U.S. society, in particular its members living in states in the Upper Midwest and the Rust Belt, that Donald Trump is a politician who puts U.S. interests first and does not shy away from any confrontational steps to protect them.

- Under the so-called “phase one” deal signed on January 15, 2020, Washington and Beijing managed at least partially to ease existing tensions as the United States pledged to abandon a fresh round of tariffs while cutting fees for $120 billion of Chinese goods from 15 percent to 7.5 percent. Meanwhile, China vowed to boost imports of services and industrial goods from the U.S. by $200 billion throughout 2020 and 2021, over a baseline of $186 billion in total imports in 2017. Commitments included $78 billion in additional manufacturing purchases, $54 billion in energy purchases, $32 billion more in farm products, and $38 billion in services. Amid the pandemic and unrealistic requirements, China managed to meet a 58 percent target, which was $99 billion out of $173.1 billion.

- Between 2017 and 2020, the negative balance of trade ties with China shrank from $375.167 billion to $310.8 billion. At the same time, the total deficit in trade in goods hit $916 billion, a 21 percent decrease compared to 2016. So the trade war helped reduce the trade deficit with China yet deepened the negative balance of trade with other industrial countries like Taiwan, Vietnam, and Mexico. Deficit reduction came from a drop in imports from China ($539.24 billion in 2018 and $451.65 billion in 2019) with a slight rise in export figures ($120.29 billion in 2018 and $124.65 billion in 2020).

- The customs tariffs introduced at the request of Donald Trump are in fact a consumption tax that elevated costs for U.S. consumers and industries dependent on imported goods. Since their introduction in 2018, fees increased customs revenues by some $80 billion. Meanwhile, some available data shows that costs incurred range between 0.23 percent, 0.5 percent, and 0.7 percent of the GDP growth in 2020.

- This is yet far from offering up a solution to the most serious problem, or the far-reaching interference of the Chinese state in its domestic economy. As most of the trade tariffs remained in force, Beijing and Washington have still a long way to go before reaching a full agreement. Issues like subsidies, intellectual property protection, relations between Chinese companies and state agencies, and highly restricted access to many fields of the economy have been one of several points of contention between China and the United States.

- A new batch of sanctions targeting the Chinese tech giant Huawei that the U.S. Department of Commerce introduced in May and August 2020 was an obstacle for any businesses using American software and machinery to trade goods and tech solutions. The decision made by the Trump administration crippled the Chinese company’s access to cutting-edge processor chips and software, a move that could curb its worldwide expansion in the long run.

The origins of the U.S.-China trade “war”

Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential race riding high on the wave of slogans like Make America Great Again and America First, both aimed to woo voters living in regions most affected by deindustrialization processes while being at a lower level of development[1]. The balance of victory tipped to Trump mostly with votes from states in the Upper Midwest and the Rust Belt[2] where Trump made a proposal to refurbish U.S. industry and restore jobs. In recent decades, these states have lost many production facilities as a result of relocating more labor-intensive industries to China and other developing countries. Between 1979 and 2010, the United States lost 7.9 million jobs in the industry, of which 42.8 percent, or 3.4 million, disappeared in 2000–2007 while a further 29.7 percent, or 2.4 million were gone between 2007 and 2010, thus during and after the global recession[3]. The model of free trade and globalization promoted over a few decades brought most profits to transnational corporations and narrow milieux of the financial elites while being detrimental to the lowest-earning and domestic industry[4]. Meanwhile, the wage and education gap grew in the United States[5] [6], building up social frustration among the lowest-earning. Immigration further aggravated frictions in the country[7] as many Trump supporters believed it was a threat to U.S. identity and its economic opportunities. During the turbulent campaign, the Republican Party candidate channeled some of this discontent into China, accusing Beijing of attempts to drain the U.S. economy, a move possible amid the incompetence of previous administrations. China’s entrance into the World Trade Organization was in his opinion “the worst trade deal in U.S. history” and enabled “the greatest jobs theft” the country has ever seen[8]. Donald Trump laid out a list of top allegations against China that included intellectual property theft worth some $300 billion per year[9], forced technology transfers, currency manipulation, state subsidies, and the mounting trade deficit[10]. Amid them, attention was drawn to a drop in the trade deficit of $375.42 billion in 2017[11] and the restoration of jobs. President Donald Trump vowed to reformulate his country’s principles of cooperation with China to make them reap benefits to the United States in the first place. With a new policy, the Trump administration sought to put an end to Washington’s conciliatory stance toward Beijing while allowing the United States to restore its previous might it had lost as a result of some past negligences. “The era of economic surrender will finally be over,” Donald Trump said in a speech in Pennsylvania, adding “we will make America great again for all, greater than ever before

The political weight of slogans targeting China and domestic conditions should not obscure the systemic nature of the Washington-Beijing rivalry. Donald Trump played the role of a catalyst, with his policy speeding up changes in the perception of both members of the elite and society. China began to be depicted as a strategic rival that poses a threat to the interests while being part of a distinct civilization and fostering different values[13]. The shift in how China was seen surfaced much earlier, though never before had anyone expressed this in such a blatant way as Donald Trump did. What occupied a pivotal role in the decision to start the U.S.-China trade war was structural changes in these two’s balance of power. Since the late 1970s, China has hit annual gross domestic product growth averaging 9.5 percent, to $14.14 trillion in 2017 up from $305 billion back in 1980[14]. In 2021, China was the world’s only major economy to rise by 2.3 percent while the latest reports show that the country’s GDP is set to become the largest one by 2028[15]. China’s tremendous economic success became what the World Bank referred to as “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history[16].”

The change was qualitative in some domains too. China has become one of the world’s leaders in artificial intelligence and telecommunications technologies while having an appetite to take on the role of the top global player in areas like renewable energy, robotics, and processor chips. In 2018, Beijing spent $462.5 billion on research and development (R&D), thus slightly less than the United States ($551.5 billion) yet more than the EU ($428.5 billion) and Japan ($173.3 billion)[17]. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China’s research and development expenditure took up a record 2.4 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020, a huge increase compared to the early 21st century when it stood at just 1 percent[18]. Under the 14th Five-year Plan period, the spending is set to boost by 7 percent annually between 2021 and 2025. China is pushing for moving from the global assembly plant to a design center and a production facility for highest-added value products. Between 2010 and 2020, Chinese authorities applied a raft of policies, including Made in China 2025, New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (新一代人工智能的发展计划), China Standard 2035 (中国标准2035), and National Guideline for the Development and Promotion of the IC Industry (国家 集成电路 产业 发展 推进 纲). According to the government-run think tank CCID, an institution under the Ministry of Science and Industry, between 2020 and 2025, spending on new infrastructure may stand at between 10 and 17.5 trillion yuan ($1.43–2.51 trillion)[19]. “New infrastructure” includes 5G wireless network, industrial Internet, modern transport, data centers, artificial intelligence, high voltage transmission infrastructure, and electric vehicle charging stations. Beijing’s activities present a tough challenge to the economic position of world players like the United States, the European Union, and Japan––the world’s top tech leaders since the end of World War II.

With the development of the Chinese economy came a proportional increase in its defense expenditure as Beijing allocated 1.9 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) to the military. China boosted its military spending to $264.45 billion in 2019, becoming the world’s second-biggest spender only to the United States whose defense expenditure hit $718.69 billion, according to the estimates from the Sweden-based SIPRI Institute[20]. In its policy, Beijing has begun a transition from its strategy of “keeping a low profile” (韬光养晦) in international affairs towards a way more assertive “great power diplomacy” (具有中国特色的大国外交) and efforts to push forward “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (中国民族的伟大复兴). China’s mounting military might altogether with the revisionist policy followed by the Communist Party of China (CPC) became what Washington considered the top threat to US security, inseparable from China’s economic rise based upon the asymmetry of the market.

U.S. Interests

It is Washington, which sees both the quantitative and qualitative growth of China’s power as the top challenge of the 21st century, that kicked off the sharp economic competition with Beijing[21]. The latter saw its four decades since initiating what is named as the “opening reforms”, in particular past 2001, as a “window of opportunity” enabling huge financial progress. In consequence, this is the first time the United States has come to grips with a country that is capable of undermining Washington’s “mild hegemony”, both when military and economic matters are at stake. It is in America’s best interest to maintain a profound influence on world politics and global economy, which allows Washington to keep its advantageous strategic position and a Western vision of world order declaratively built upon core democratic values. The current model of world trade has enfeebled the U.S. industry, made developed countries dependent on Chinese imports, and nurtured inequalities within U.S. society. When declaring a trade war, the Trump administration made it clear: globalization under the existing conditions fostered the asymmetric growth of China and other actors worldwide with the loss of the United States, its interests, and people. The top goal is to balance economic ties so that both sides could use it evenly and to cripple the Chinese dynamics of development to bar the country’s economy to overtake the United States as the world’s leading superpower. It is not about isolating China completely as now it is impossible to do so amid resistance over China’s being highly integrated into global value chains and its substantial intertwine with U.S. partners and allies. What is a conundrum for U.S. officials is that many American manufacturers remain dependent on the Chinese market, in particular for the processor chip sector as well as the automotive, aerospace industry, agricultural industry, and––to some extent––entertainment.

The international commercial expansion of titans like Huawei, Lenovo, ZTE, Xiaomi, as well as Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent, or the BAT, represents a threat to the dominance of U.S.-based corporations with their influence spanning worldwide. Barring them all from developing any further through a set of tariffs and punitive measures is one of the core goals of the trade battle and––once attained––this will allow United States information and communications technology (ICT) firms to secure their business interests. Chinese state-subsidized companies are top rivals of those sitting across the United States in domains like smartphone manufacturing (Apple–Huawei/Xiaomi), 5G technology (Cisco–Huawei/ZTE), and artificial intelligence where U.S.-based Google and Facebook see high competition from China’s Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. What is the ultimate goal of Communist Party of China officials is to grow a self-reliant approach in all critical industry and service sectors to sustain the high rate of development and pursue a more unilateral foreign policy.[22] For Beijing, it is particularly vital to build processor chips at home as in 2020 China imported $350 billion worth of microchips[23]. The country is dependent on the imports of cutting-edge integrated circuits from Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. In its analysis, the Semiconductor Industry Association, in short SIA, says Chinese manufacturers stand for roughly 5 percent and 16 percent of the global and domestic market[24], respectively. The authorities in Beijing are making efforts to change this, a move that means a drop in the profits made by U.S. tech businesses like Intel, Broadcom Qualcomm, or Micron and a weaker role of the United States in production chains. Not only would an autonomous and competitive chip manufacturing sector cement China’s position at the expense of the United States, but this could also unlock a more confrontational policy unconstrained by any U.S. sanctions.

Chinese interests

Beijing has its fundamental goal to keep unchanged the existing free trade model that allows the country to beat record-high trade surpluses, transfer technology and human resources, and deposit savings into foreign investments. The decades-long model of globalization gave China both tangible economic benefits and strengthened its economic intertwines with U.S. partners. That is why the government in Beijing depicts itself as a defender of free trade and multilateralism as opposed to Washington’s alleged protectionism and unilateralism[25]. This is so although both the economy of the United States and that of the European Union remain asymmetrical way more open than the Chinese one does[26]. China also received preferential trade benefits as a developing nation at the World Trade Organization though Beijing has seen huge progress since it entered the bloc in 2001. China’s ever-growing role in the global economy has basically wiped out any possibility to decouple the economy on a large scale and weakened Washington’s influence on its key allies.

Despite promises of sustainable, high-rise, and innovation-based development schemes, or boosting the role of consumption and internal market within what is known as the dual circulation strategy, China’s economic glory remains heavily reliant on whether foreign markets welcome its businesses as well as on the economic situation worldwide. Also, the Covid-19 pandemic increased the worldwide demand for medical and electronic goods while China could record its all-time high export results in consequence[27]. Donald Trump’s economic policy has dealt a blow to China right when Beijing is faced with the biggest development challenges since economic reforms that took place after Mao’s death. An economic growth model based on a cheap workforce, investments, and the overuse of raw materials are no longer sustainable, though. One of Earth’s fastest aging[28] and most indebted societies[29], China has the world’s biggest middle class with a growing appetite for consumerism. The Communist Party of China owes its legitimacy to its successful attempts to improve the people’s financial situation, thus a downturn of economic development prospects may undermine it. The U.S.-China trade war has impeded efforts made by the Xi Jinping administration to maintain a high rate of economic growth while paving the way for consolidating power. With U.S. policy toward China, the Chinese Communist Party got a clearly defined opponent who seeks to choke off Bejing’s development, seen as “an inevitable historical process.” What Washington is now doing shows the credibility of a Chinese-endorsed hegemonic narrative and its policy of unilateralism, the latter being aimed at mobilizing society and offering a stronger legitimacy to incumbent authorities.

Detailed outline

Once sworn into office in January 2017, Donald Trump engaged in a dialogue with China to bridge economic differences without resorting to a customs war. On April 6, 2017, the U.S. leader met with Xi Jinping at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida, a reunion that became a symbol of the policy whose number one mission was to seek an agreement. The two presidents agreed on a new 100-day plan for trade talks that allowed them to develop a solution that suited both[30]. On May 11, the two countries signed a preliminary supply deal and China undertook to open up its market to U.S. beef, biotechnology products, liquefied natural gas, and financial services[31]. Nonetheless, the two states did not negotiate any further concessions until July 2017 and this paved the way for a more confrontational course.

As talks somewhat stalled, the Trump administration imposed customs fees ranging from 7.5 and 25 percent on $277 billion worth of Chinese goods from the 2019 trade baseline over eighteen months from July 2018 to May 2019 under Section 201 and 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 and Section 232 of the Trade Act of 1962[32]. U.S. sanctions covered a list of products, including telecom gear, industrial machinery, computers and semiconductors, clothing, vehicle parts, furniture, and household appliances. In a retaliatory response to U.S. tariffs, Beijing hit back with additional tariffs ranging from five percent to 25 percent on $76.8 billion worth of U.S. goods.

Alongside customs policy, U.S. sanctions targeting Chinese business giants have turned into an important vector of the federal government’s efforts. On May 15, 2019, President Trump issued an executive order giving the U.S. Department of Commerce powers to block Huawei from selling its telecoms gear and services in the United States. The Chinese firm––as well as 70 affiliates––was added to the so-called Entity List in a move that barred them from doing business in the United States unless they have a special license. The U.S. Department of Commerce agreed to renew the license on multiple occasions since punitive measures had been in force yet the latest one expired on August 13, 2020. With new regulations in force, companies like Google, Intel, Qualcomm, or Microsoft have to cut business ties with Huawei once it gets no permit from the U.S. authorities. Cut off Huawei phones from Android updates, the Chinese telecom giant might encounter what could become a major hurdle on its path to worldwide expansion. Introduced in May and August 2020, the latest sanctions banned any American companies and those foreign-based using American software and machinery from supplying Huawei in yet another move dealing a blow to the Chinese giant. As U.S. companies hold the reins in this sector, the U.S. government got a powerful tool of pressure that forced Huawei’s partners to obey sanctions. The decision from the U.S. Department of Commerce proved fateful for the Chinese telecoms giant that no longer had access to the world’s cutting-edge processor chips underpinning the core of the company’s flagship products.

After months-long talks, the „phase one“ deal was inked on January 15, 2020, a move that brought a partial de-escalation to the conflict. The Trump administration scrapped new tariffs while reducing duties from 15 to 7.5 percent on $120 billion worth of Chinese products. Yet the agreement will still leave tariffs on $250 billion in Chinese products in place. Meanwhile, China vowed to boost imports of services and industrial goods from the U.S. by $200 billion throughout 2020 and 2021, over a baseline of $186 billion in total imports in 2017. Commitments included $78 billion in additional manufacturing purchases, $54 billion in energy purchases, $32 billion more in farm products, and $38 billion in services.

In addition to increased import figures, China said it will open market access for U.S.-based financial and insurance companies like Visa, MasterCard, or JP Morgan Chase. Though a wider opening up of Chinese markets to foreign companies was first initiated back in 2017, it was only with the pressure from the Trump administration that the entire process could accelerate.

Under the deal, the resolution of trade disputes would now be through what was named as the bilateral Evaluation and Dispute Resolution Arrangement, in short BEDRA, with either party being eligible to withdraw from some provisions of the deal if a dispute cannot be resolved[33]. The two sides got room for maneuver, with the United States being able to bring back tariff barriers and China quitting increased import volumes.

Profits and losses

Economically, with their newly imposed customs tariffs, Washington and Beijing saw a steep decline in the total value of bilateral trade flows. In 2020, it rose to $560 billion while in 2019 it stood at $558.87 billion, or far less than $659.82 billion in 2018[34]. Between 2017 and 2020, the negative balance of trade ties with China dropped to $310.8 billion from $375.167 billion while the total deficit in trade in goods hit $916 billion, a 21 percent decrease compared to 2016[35]. So the trade war helped reduce the trade deficit with China yet deepened the negative balance of trade with other industrial countries like Taiwan, Vietnam, and Mexico. Deficit reduction came from a drop in imports from China ($539.24 billion in 2018 and $451.65 billion in 2019) with a slight rise in export figures ($120.29 billion in 2018 and $124.65 billion in 2020). The United States attained the goal of the reduced deficit in the balance of trade with China through its efforts to boost the value of imports from elsewhere. Amid the pandemic and unrealistic requirements, China managed to meet the target in 58 percent, which was $99 billion out of $173.1 billion.

It is somewhat a misguided action to focus on eliminating the deficit in bilateral ties without any reference to its structural sources. The U.S. negative balance stems from some macroeconomic factors related to an imbalance in domestic savings and investment. The demand for capital in the U.S. economy stands higher than the gross savings of households, businesses, and the government sector, which results in the rise of interest rates. With floating exchange rates and open economy schemes, foreign capital inflows bridge the gap between the shortages in supply and demand for capital. As the United States sees more investment projects from the outside, the country is able to consume way more than it can produce, a situation that produces a huge trade deficit. The global demand for dollars keeps its exchange rate at a high level, which boosts America’s poorer export performance and prompts the country to import more. To eliminate the deficit would thus not consist of curbing the economic imbalance in ties with some countries, but of reshaping the U.S. economy.

In 2019, U.S. GDP growth was 2.3 percent, which is down from 2.9 percent in 2018 and just below 2.3 percent in 2017, thus since Donald Trump was sworn in as the next U.S. president. Chinese economy saw back then a series of falls, with its official economic growth coming in at 6.9 percent in 2017, 6.6 percent in 2018, and 6.1 percent in 2019. With fees, introduced in 2018, the United States has received $80 billion to the federal budget. Yet according to some available data, the country’s GDP might have seen 0.23 percent[36], 0.5 percent, or even 0.7 percent worth of decline[37].

Before the pandemic-related crisis hit, the U.S. job market had seen favorable employment dynamics. The United States saw favorable dynamics in its labor market, with 6.4 million jobs added since 2017, while the jobless rate fell to 3.5 percent in September 2019, or its lowest level since 1969[38]. Yet these shifts should have no link to the trade war as available data shows that the number of jobs dropped by 180,000 or 245,000 as consequence, various estimates[39] indicate[40].

But an increase in trade barriers did not harm foreign direct investments (FDI) into China. FDI inflows into China increased to $139 billion in 2018, by $5 billion year-on-year, while in 2019, inbound foreign investment into China rose to around $140 billion[41] and $144.7 billion in 2020, according to data released by the UN[42].

Among sectors most affected by tariff barriers was the U.S. automobile industry. U.S.-manufactured vehicles see between 40 percent and 50 percent of their parts and components coming from other countries like Mexico (37 percent), China (12 percent), and Canada (11 percent)[43]. Also, U.S. farmers were one of the most visible casualties of the U.S.-China trade war. Before the tariff hike, in 2017, the U.S. exported to China $19.5 billion worth of agricultural goods. Amid the trade war, U.S. farms export to China fell to just $9.1 billion in 2018, marking a 53 percent drop. Farmers were said to have incurred massive losses due to the trade battle to be offset with a $16 billion farm aid package announced by the federal authorities to mollify farmers hit by retaliatory tariffs[44]. The whole picture improved in 2019 and 2020, with export values standing at $13.8 and $13 billion, respectively, with setting up high expectations for 2021[45]. While U.S. losses from the China trade war were rather slight, support for Trump from Midswest farmers turned out of key importance for the 2020 presidential runoff.

In addition to the economic conundrum, the trade war caused reputational damage to Washington. Targeting partners and allies with customs fees also undermined America’s reputation as a free trade defender it has built over a couple of decades. China could simultaneously create its image of a “responsible shareholder” by sealing economic deals such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade agreement with Asian nations, and the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with the European Union.

Economic damages from U.S. tariffs were yet not big enough to persuade Chinese officials to transform the core of their country’s economy. The trend to relocate plants from China to the United States and elsewhere may in the long run turn out to be way more unfavorable than expected.

Implications for the EU and Poland

Robust intertwines between the EU economies and the U.S. and Chinese markets mean that the trade war sends shockwaves also beyond Washington’s tariffs on China. For the European Union the United States is the top trading partner (plus services) while China ranks first in trade exchange[46]. Since Washington imposed trade sanctions on Beijing, the U.S.-EU trade exchange has risen significantly. U.S. goods exports to the EU in 2019 rose to $337 billion from $283.2 billion back in 2017. Similarly, U.S. imports from Europe grew to $514.88 billion from $434.9 billion[47]. Despite President Donald Trump’s pledges to curb trade deficit, its total value with the European Union jumped by $25 billion between 2017 and 2019. China is the EU’s second-largest trade partner after the United States. In 2020, EU member states exported to China €202.5 billion of goods while its import figures were €383.5 billion, according to data from Eurostat. EU countries had high deficits hitting €181 billion[48].

Of all EU economies, Germany served a leading role in trade ties with Beijing, with its exports to China hitting a record €96.42 billion and imports of €82.04 billion (19 percent)[49]. For comparison, in 2020, Poland exported to China $4.3 billion of goods while imports hit $27 billion[50]. Poland’s exports to China occupy a minor role in the country’s total export numbers, or some 1 percent, which is less than the country’s exports to Turkey, Norway, or Slovakia. By contrast, China comes with 12 percent of Poland’s overall imports. The U.S.-China trade war should not pose a hurdle to the latter’s exports to Poland, as it is in Beijing’s best interest to conquer new markets. What may have more of an effect on goods flows could be the epidemic of Covid-19 coronavirus as it is likely to put a stick in the spokes of many supply chains worldwide.

From October 2018 onwards, Germany––for which China is the top trading partner accounting for Berlin’s $200 billion in turnover since 2017––has seen consecutive drops in its industrial output, of more than 5 percent in November and December 2019[51]. Other negative trends are also apparent for the country’s gross domestic product growth rate that stood at 0.6 percent in 2019 and -5 percent in 2020. Germany sees Poland as its top export market and where it purchases goods. Their annual trade turnover is higher than $100 billion, with Poland’s exports to Germany including essentially vehicle parts. Similar––or even deeper–– trade ties are noticeable for countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia. A decline in Chinese consumption will lead to negative consequences for the German economy, with all Central and Eastern European countries doomed to losses.

Trump’s trade war with China cemented Europe’s tendency toward building a strategic economy and pursuing a more autonomous foreign and economic policy[52]. This came out as the European Union was sealing its investment deal with China in late December 2020 and early January 2021. The European Commission did not wait for a new U.S. president to be sworn in as it announced having “substantially” concluded talks with China[53]. Europe’s stance stood in stark contrast to what the incoming Joe Biden administration had claimed before, expecting EU senior officials to consult any decisions with the new U.S. leader. Nonetheless, the deal still awaits ratification by the European Parliament as both sides may introduce sanctions amid human rights abuse in Xinjiang. The pandemic-induced recession will foster closer economic ties with China, in particular in EU countries being highly reliant on the Chinese market. What happened in 2020 emboldened a slew of risks that emerged as production chains were located outside the European Union, a situation that might relocate some of its links to Europe. The intensifying technology competition will limit the transfer of sensitive tech solutions to China and the process of acquiring businesses of top strategic importance for Europe’s innovation and security.

Conclusions and forecasts

Inked by the U.S. and Chinese officials on January 15, 2020, the „phase one“ deal was nothing but a “truce” in these two’s economic rivalry slated to dominate the first half of the 21st century. This is yet far from offering up a solution to the most serious problem, or the far-reaching interference of the Chinese state in its domestic economy. As most of the trade tariffs remained in force, Beijing and Washington have still a long way to go before reaching a full agreement. For the Trump administration, it was a mistake to fix on the trade deficit with China and the negative balance came from the macroeconomic structure of the U.S. economy. It is impossible to solve such a complex conundrum resulting from the position of the dollar worldwide and free movement of capital by introducing tariffs against some countries. Due to steps taken between 2017 and 2021, the United States indeed lowered its trade deficit with China, but its imports from countries showing a comparable industrial profile went up, thus aggravating the total U.S. trade deficit. Those that sustained the cost of fees were U.S. citizens and businesses, a situation that deprived many of their jobs and brought a slowdown in GDP growth. Notwithstanding those, U.S. steps towards Huawei should be assessed positively. Sanctions against the export of software and processor chips and a broad diplomatic action effectively curbed the expansion of the Chinese giant. Also, other Chinese businesses––Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, and realme––can take advantage of Huawei’s enfeebling position. As the U.S. government made use of its dominance in the processor chip sector, state authorities in Beijing will ramp up efforts to become self-sufficient in developing these tech solutions and software.

America’s partial retreat from the path of globalization it has followed so far has come as an extra hurdle to the Xi Jinping administration, now facing the challenge of how to transform the state’s development model and the slowdown in GDP growth. In addition to domestic consumption and business investments, exports and innovation schemes remain what is referred as to sustainable sources of growth unlike those fuelled by unprofitable credit investments. The great-power rivalry along with economic and civilization clashes will serve as an obstacle to economic cooperation.

Coming to a seemingly very beneficial understanding for the United States has bolstered Donald Trump’s position before the November 2020 presidential elections that he lost. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, China could meet its export targets in just 58 percent, or $99 billion out of $173.1 billion. The agreed-upon document contains a clause that allows either party to step away from its provisions if the two sides are unable to work out a joint solution under bilateral mechanisms. Under this scenario, U.S. and Chinese authorities got a lot of room for maneuver while being able to pull out if they consider the deal is unsatisfactory.

In the short run, the Joe Biden administration is unlikely to relax customs tariffs and sanctions. In addition, Donald Trump as the Republic Party candidate built some of his campaign on accusing Biden of his allegedly conciliatory stance on China while blaming the Democrat for neglecting the American working class. Aware of the perception shift among members of the U.S. elites and criticism of Barack Obama’s policies, Joe Biden will avoid any decisions being a comfortable excuse for the Republicans to attack. The incumbent president may even tighten his stance on processor chips and the transfer of sensitive technologies. Whether to lift customs duties or not will hinge on progress in talks on structural problems that have yet to be resolved. The pivotal role of subsidies and state-run businesses in China’s economic policy does not mean any prompt decisions as these would prevent the Chinese Communist Party from controlling the state economy and its development directions. Another factor poised to play its part is China’s ties with Indo-Pacific states. In March, U.S. Indo-Pacific Coordinator Kurt Campbell allegedly informed China that any potential economic relaxation process would not happen if Beijing did not improve relations with Australia.

The Biden administration is not likely to rejoin the Trans-Pacific Partnership by 2022, either, as this would trigger a vocal reaction from both Democrats and Republicans, fearful of a violent industrial reaction and job losses. The pandemic dealt a blow to many industrial facilities so relaxing the export policy to the U.S. could cost new state authorities some reputation damage. In his first days as U.S. president, Joe Biden announced an executive action Made in America[54] ensuring that the federal government was investing taxpayer dollars in American businesses. “Our trade policy has to start at home, by strengthening our greatest asset—our middle class—and making sure that everyone can share in the success of the country,” the Democratic Party candidate said in his May 2020 article for Foreign Affairs[55]. “As president, I will not enter into any new trade agreements until we have invested in Americans and equipped them to succeed in the global economy[56],” he went on saying. Similarly, on February 24, 2021, President Biden issued an executive order on “America’s Supply Chains,” which directs several federal agency actions to secure and strengthen America’s supply chains[57].

[1]Among U.S. states won by Donald Trump were those having the lowest GDP per capita and struggling with stagnation and high unemployment rates (Mississippi, Arkansas, West Virginia, Idaho, Montana, Alabama)

[2]Michael McQuarrie, The revolt of the Rust Belt: place and politics in the age of anger, The British Journal of Sociology, Volume 68, Issue S1, 2017.

[3] Harold (Hal) Wolman, Eric Stokan, and Howard Wial, Manufacturing Job Loss in U.S. Deindustrialized Regions—Its Consequences and Implications for the Future: Examining the Conventional Wisdom, Economic Development Quarterly 2015, Vol. 29(2), p. 102.

[4]Matthew C. Kline, Michael Pettis, Trade Wars Are Class Wars, Oxford University Press: London, 2020.

[5]Elise Gould, Decades of rising economic inequality in the US Testimony before the US House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, March 27, 2019, https://www.epi.org/publication/decades-of-rising-economic-inequality-in -the-us-testimony-before-the-us-house-of-representatives-ways-and-means-committee /

[6]Raj Chetty, John Friedman, Emmanuel Saez, Nicholas Turner, Danny Yagan, Income Segregation and Intergenerational Mobility Across Colleges in the United States, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 135, No. 3, 2020, pp. 1567–1633.

[7]Raul Hinojosa, Edward Telles, Trump Paradox: How Immigration and Trade Affected Voting in 2016 and 2018, UCI Center for Population, Inequality, and Policy, November 2020.

[8]Road to the White House 2016. Donald Trump Remarks in Monessen, Pennsylvania, June 28, 2016,

[9]The Report of the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, IP Commission Report, 2013; Findings of the Investigation Into China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation Under Section 301 of The Trade Act of 1974, United States Trade Representative, March 2018.

[10]US trade in goods with China, US Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

[11]Ibidem.

[12] “The era of economic surrender will finally be over”.

[13]Communist China and the Free World’s Future Michael R. Pompeo, Secretary of State Yorba Linda, California Richard Nixon Presidential Library, July 23, 2020, https://2017-2021.state.gov/communist-china-and-the-free- worlds-future-2/index.html.

[14]GDP, current prices Billions of U.S. dollars, International Monetary Fund (IMF), https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/CHN

[15] Masahi Uehara, 6th Medium-Term Forecast of the Asian Economy (アジア経済中期予測 (第6回/2020-2035年, Japan Center for Economic Research, December 2020.

[16]China At-A-Glance, World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/testpagecheck

[17] Gross domestic spending on R&D, OECD, https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm.

[18]China’s R&D spending rises to record 2.4% of GDP in 2020, China Global Television Network, March 7, 2021, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-03-01/China-sRD-spending-rises-to- record-2-4-of-GDP-in-2020-YhqaulWMx2 / index.html.

[19] “新 基建” 超级 风口 , 直接 投资 超10 万亿 , 带动 投资 超 17 万亿, April 20, 2020, https://www.sohu.com/a/389606303_100159565.

[20]Military expenditure by country, in constant (2018) US$ m., 1988-2019, SIPRI, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/Data%20for%20all%20countries%20from%201988%E2%80%932019%20in%20constant%20%282018%29%20USD.pdf.

[21]National Security Strategy of the United States of America, The White House, December 2017; Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World, U.S. Department of State Headquarters Harry S. Truman Building Washington, D.C. February 4, 2021.

[22] Proposal of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party on Drawing Up the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives for 2030 (授权 发布) 中共中央 关于 制定 国民经济 和 社会 发展 第十四 个 五年 规划 和 二 〇 三 五年 远景 目标的 建议.

[23]Masha Borak, China boosts semiconductor production in 2020, but imports keep apace, frustrating self-sufficiency goals, South China Morning Post, January 19, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/tech/policy/article/3118327/china- boosts-semiconductor-production-2020-imports-keep-apace.

[24]Semiconductor Industry Association Factbook 2021, April 21, 2020, https://www.semiconductors.org/resources/factbook/.

[25]Let the Torch of Multilateralism Light up Humanity’s Way Forward Special Address by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China At the World Economic Forum Virtual Event of the Davos Agenda January 25, 2021; Jointly Shoulder Responsibility of Our Times, Promote Global Growth Keynote Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China At the Opening Session Of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2017, Davos, January 17, 2017.

[26]Terry Miller, Anthony B. Kim, James M. Roberts, 2021 Index of Economic Freedom, Heritage Foundation.

[27]China’s foreign trade hits record high in 2020 with trend-bucking growth, Xinhua, January 14, 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-01/14/c_139666793.htm

[28]Jiang, Q., Yang, S. & Sánchez-Barricarte, J.J. Can China afford rapid aging?. SpringerPlus 5, 1107 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2778-0

[29]China’s debt tops 300% of GDP, now 15% of global total: IIF, Reuters, July 18, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-debt-idUSKCN1UD0KD.

[30]Trump, Xi agree to a 100-day plan to discuss trade issues, Reuters, April 7, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-plan-idUSKBN17932I

[31]Ayesha Rascoe, Michael Martina, US, China agree to first trade steps under 100-day plan, Reuters, May 12, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-trade-idUSKBN188088

[32]Congressional Research Service, Trump Administration Tariff Actions: Frequently Asked Questions, December 15, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45529.pdf

[33]Economic and Trade Agreement Between the Government of the United States Of America and the Government Of The People’s Republic Of China, 15th January 2020, Art. 7.4.

[34]US trade in goods with China, US Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html

[35]Monthly US International Trade in Goods and Services, Release Number: CB 21-17, BEA 21-04, US Census Bureau, February 5, 2021.

[36]Erica York, Tracking the Economic Impact of US Tariffs and Retaliatory Actions, Tax Foundation, September 18, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/tariffs-trump-trade-war/#imposed

[37]Congressional Research Service, Trump Administration Tariff Actions: Frequently Asked Questions, December 15, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45529.pdf

[38]The Employment Situation, Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor, September 2019, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_10042019.pdf

[39]Erica York, Tracking the Economic Impact of US Tariffs and Retaliatory Actions, Tax Foundation, September 18, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/tariffs-trump-trade-war/#imposed

[40]The US-China Economic Partnership, The US-China Business Council, January 2021.

[41]United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, World Investment Report 2019p. 4.

[42]Orange Wang, China FDI rose to a record level in 2020 despite coronavirus, fastest growth rate in five years, South China Morning Post, January 20, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3118469/ china-fdi-rose-record-level-2020-despite-coronavirus-fastest

[43]U.S. Consumer & Economic Impacts of U.S. Automotive Trade Policies, Center for Automotive Research, 2019, https://www.cargroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/US-Consumer-Economic-Impacts-of-US-Automotive-Trade-Policies-.pdf

[44]Humeyra Pamuk, Trump administration announces $16 billion farm aid plan to offset trade war losses, Reuters, May 23, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-china-aid-idUSKCN1ST1F6

[45]US agricultural exports to China to hit record high in 2021: USDA, Xinhua, February 19, 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/northamerica/2021-02/19/c_139752202.htm

[46]Euro area international trade in goods, Eurostat, February 15, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/portlet_file_entry/2995521/6-15022021-BP-EN.pdf/e8b971dd-7b51-752b-2253-7fdb1786f4d9

[47]Trade in Goods with European Union, US Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c0003.html

[48]Trade in Goods with European Union, US Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c0003.html

[49]China-EU – international trade in goods statistics, Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/China-EU_-_international_trade_in_goods_statistics#Trade_with_China_by_Member_State

[50]Maciej Kalwasiński, Polska ma rekordowy deficyt w handlu z Chinami. Dlaczego to bez znaczenia?, January 25, 2021, https://www.bankier.pl/wiadomosc/Polska-ma-rekordowy-deficyt-w-handlu-z-Chinami-Dlaczego-to-bez-znaczenia-Tlumaczymy-8043178.html.

[51]Germany Industrial Production Growth Index, CEIC, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/germany/industrial-production-index-growth

[52]No way back: Why the transatlantic future needs a stronger EU, Policy Department for External Relations Directorate General for External Policies of the Union PE 653.619 – November 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/ 2020/653619 / EXPO_IDA (2020) 653619_EN.pdf

[53]EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), European Commission, January 22, 2021, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=2237

[54]President Biden to Sign Executive Order Strengthening Buy American Provisions, Ensuring Future of America is Made in America by All of America’s Workers, The White Hose, January 25, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/25/president-biden-to-sign-executive-order-strengthening-buy-american-provisions-ensuring-future-of-america-is-made-in-america-by-all-of-americas-workers/

[55]Joe Biden, Why America Must Lead Again: Rescuing US Foreign Policy After Trump, Foreign Affairs, April/May 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again

[56]Joe Biden, Why America Must Lead Again: Rescuing U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump, Foreign Affairs, April/May 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again

[57]Executive Order on America’s Supply Chains, The White House, February 24, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/02/24/executive-order-on-americas-supply-chains/

Paweł Paszak – University of Warsaw graduate in International Relations (East Asia Studies) and a former scholarship student at University of Kent (United Kingdom) and Hainan University (PRC). PhD Candidate at University of Warsaw/War Studies University and a researcher in projects for Poland’s Ministry of National Defence. Expert at the Institute of New Europe (INE) and the author of analyses and articles concerning US-China trade war, China’s economic transformation, and technological rivalry.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.