SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 23 May 2022 Author: Aleksander Olech, PhD

2022 French Presidential Election

The French presidential election was fundamental to the world order. The Western European power boasts the EU’s biggest army, the world’s largest exclusive economic zone, and nuclear arsenal while its troops are deployed to five continents. So far France has made modest efforts to contain Russia’s imperialist policy while senior French officials often praised cordial ties with the authorities in Moscow. Nevertheless, the Western European country has become a pillar of security for Central and Eastern European countries, including Poland, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

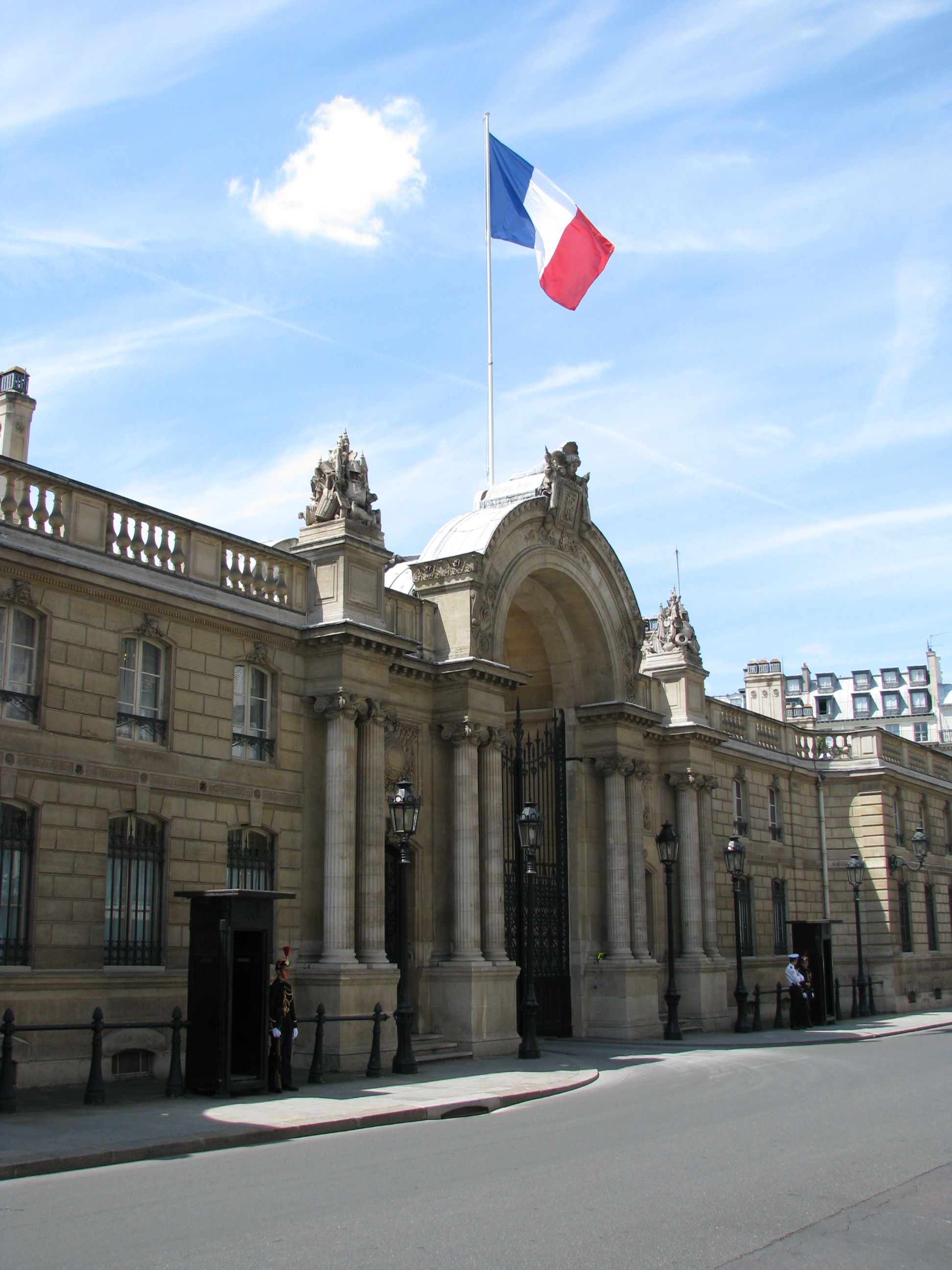

Emmanuel Macron’s return to the Elysée Palace makes it easier for the blocs, in particular NATO and the European Union, to follow their political and economic projects and deepen ties between the West and the East. Although not a perfect choice for Poland, the sitting president of France is the best for maintaining stability throughout Europe.

It all started with rivalry

On April 10, 2022, twelve candidates lined up in a contest for the French presidency. As no candidate won a majority in the first round, a runoff was held. Incumbent Emmanuel Macron and his top challenger Marine Le Pen went through to a runoff election after topping the first round poll, winning 27.84 percent and 23.15 percent of the vote, respectively. Turnout was 73.69 percent, which was the second-lowest in a presidential election. Only voters aged over 60 chose Macron who lagged behind Le Pen in all the overseas departments. This reflects the policy the incumbent president followed in the past five years. He devoted much of his attention to metropolitan France and the Arabian Peninsula. France’s overseas departments and communities served to consolidate political grip and undertake a military buildup. The sitting president failed to encourage the youth while considering reviving a pension reform, leading to discontent among France’s youngest voters. Despite that, he was a safer bet––far more moderate than far-right Zemmour or far-leftist Mélenchon.

Republicans and socialists, who ruled France alternately for sixty years and back then enjoyed even 90 percent support, now scored no more than 6.5 percent of the vote. People aged below 50 were unlikely to support them (1–2 percent). Polls show that Valérie Pécresse secured votes from people aged 70 and more (12 percent). The vote of some 80 percent of people who in 2017 backed François Fillon was distributed almost evenly throughout Macron on the one hand and Zemmour and Le Pen on the other.

Other candidates urged French people to back either Macron or Le Pen. Those who gave their endorsement to the incumbent president were Valérie Pécresse, Anne Hidalgo, Yannick Jadot, and Fabien Roussel. Far-leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon told his voters not to vote for Marine Le Pen in the runoff. Eric Zemmour, the far-right pundit, called on his voters to endorse Le Pen.

On April 24, Emmanuel Macron beat his far-right rival Marine Le Pen with 58.50 percent of the vote in the second round of France’s presidential election. The gap between them was narrower than five years ago when Macron won 66 percent of the vote, but the incumbent leader could feel satisfied with the score. Macron came out on top in a combative TV debate performance and proved the efficiency of his foreign policy. In addition, continuous efforts for nuclear energy kept prices low despite the global crisis. However, a turnout that stood at 71.8 percent may be high for Polish standards, but it marked the lowest score ever recorded in a French presidential election final since 1969. Moreover, some 8.6 percent of people cast blank or void ballots, which reflected the apathy of voters who complained neither candidate represented them.

Macron’s second term means consecutive ten-year leadership whose top focus is to make France a worldwide leader. Le Pen’s agenda concentrated on the Frenchness but French citizens opted for the relative calm amid the war in Ukraine and the new post-pandemic real. A drop in living standards or social unrest that swept the country––including the yellow vests protests––did not harm Macron’s performance.

Indeed, Marine Le Pen learned a lesson from her earlier bid for presidency as she somewhat softened her image to appease voters. But foreign media outlets labeled her views extreme and far-right, which caused great damage to her election efforts. Importantly, never before in her career has Marine Le Pen occupied any major state positions while the incumbent president served as associate general secretary of the president. He was then appointed to the French cabinet as minister of the economy, industry, and digital affairs before eventually becoming president of France. In addition, Le Pen has no major contacts worldwide while her stance resembles those of Hungary, Poland, and––to some extent––also Russia. Like in the first two states, Le Pen’s political manifesto consists in finding France isolated in the European Union. After Russia invaded Ukraine, Le Pen somewhat cut off her firm support for the Kremlin but the far-right politician is advocating the return to close Russian-French ties once the war is over. The National Rally leader also insists on energy imports and French investments on Russian soil.

How people voted

The first round of the French presidential election revealed voter choice for evidence of religious identity. Jean-Luc Mélenchon won 69 percent of Muslim votes while no other religious community threw more than 36 percent support to a single candidate. Catholics and Protestants opted for Macron while atheists seemed torn while casting their ballots for Mélenchon (30 percent), Macron (26 percent), and Le Pen (20 percent). In the runoff, 85 percent of Muslims voted for the sitting president. What played its part was their resentment towards Marine Le Pen who continued her anti-Islam discourse. Second-generation French Muslims also supported the incumbent leader. Macron secured 55 percent of the Catholic vote against 45 percent cast for Le Pen while 65 percent and 35 percent of the Protestant vote, respectively.

Polls show a clear divide between voters for the two candidates across age groups as the elderly were keener to endorse Macron. The incumbent leader would not have advanced to the runoff if there had been only for the vote of people aged between 18 and 34. Those who scored far better were Le Pen and Mélenchon. Macron won just 20 percent of the vote from people aged between 18 and 24. He yet earned twice as much support among the elderly (41 percent). Le Pen got 26 percent support from people aged between 18 and 24 and 13 percent from the elderly. Most importantly, Le Pen could gain ground with youth voters through her refreshed agenda. But she sought major changes within the European Union and the French Muslim community. This could spark social unrest, which eventually dissuaded the elderly from voting for Le Pen.

In the runoff, 61 percent of people aged between 18 and 24 chose Macron. However, as many as 41 percent of them stayed away from voting booths. Young voters who reluctantly faced the prospect of a Le Pen presidency eventually cast their ballot for Macron. Marine Le Pen commanded slightly higher support among voters aged over 50. Macron polled best among French senior citizens aged over 70––as many as 70 percent cast their ballot for the incumbent leader.

Lower-income voters whose earnings were inferior to €900 monthly were more eager to endorse the far-right contender. In terms of income, the voting data broadly paints a picture of a wealthier France that voted for the incumbent. These were 51 percent of people earning between €900 and 1,300 per month, 53 percent of voters whose monthly earnings were between €1,300 and 1,900, 65 percent of people earning between €1,900 and €2,500, and 76 percent of those earning €2,500 and more. In the first round, Macron secured 43 percent of the vote from France’s highest income voters whose monthly salary was superior to €2,500 per capita. Macron convinced 65 percent of the unemployed, which gave him a clear advantage over his far-right challenger. But what tipped the scale for Macron was vast support from pensioners. Data on employment found that Macron scored only six percentage points more than Le Pen. Those who voted for the centrist incumbent were senior management, junior managers, and senior employees while blue-collar workers, traders, and entrepreneurs chose Le Pen, but by a slim margin at 51–49 percent. Polls found that 65 percent of blue-collar workers cast their ballot for the National Rally candidate.

There was a geographical split between the two candidates. France’s post-vote map shows Macron broadly enjoying support in Paris, the west, south-west, and center of the country, while Le Pen won overwhelmingly in swathes of her north and north-eastern heartlands, the Mediterranean south, and overseas departments. Macron is seeking to pursue a global-oriented policy through the country’s overseas territories, but he does not enjoy much public support there. The sitting president won convincingly in the Pacific territories of New Caledonia and French Polynesia. Le Pen finished far ahead of Emmanuel Macron in the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, French Guyana (South America), and the two Indian Ocean islands of Réunion and Mayotte. But her winning by a wide margin does not mean that their inhabitants vote for her––in fact, many of them cast their ballot against Emmanuel Macron. In Guadeloupe, far-leftist Mélenchon scored 56 percent of the vote. Most people there voted for the far-right candidates, which gave Le Pen roughly 70 percent of the vote.

French citizens voted differently in rural and urban areas. Marine Le Pen scored 4 points better in the countryside. The National Rally candidate attracted more voters in towns with no more than 20,000 residents. Macron duly won the mid-sized (20,000–100,000 residents) and big (over 100,000 residents) cities, where he scored 56 percent and 65 percent of the vote, respectively. But his vote held up best in Paris and suburbs, winning 73 percent of the vote. Marine Le Pen scored just slightly better in cities with the highest delinquency rate

Five more years

As the vote showed, France is somewhat divided into three groups whose interests are irreconcilable: those led by Macron, Le Pen, and Mélechon. Neither of them won more than 30 percent of support in the first round. 56 percent of French people voted for far-right and far-left parties whose candidates were Zemmour, Le Pen, and Mélenchon. These three factions have distinct views on domestic and foreign policy. French citizens in metropolitan France and overseas departments have indeed elected their president but now have no clue how to channel their endorsement. There is a growing belief many French people voted against Le Pen––and not for Macron. The French presidential election sparked protests. France is torn into the centrist, the far-right, and the far-leftist parties before the upcoming parliamentary vote.

What does the French presidential election mean for Poland? Indeed, Macron does not turn much attention to his country’s relations with Poland but his success is crucial for the European security architecture. Keeping France in NATO while introducing no major changes to the European Union and throwing continuous military support for Eastern European states are key for Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltic countries. Poland should seek further opportunities for its ties with France to flourish. Macron is not a perfect choice. But he now cannot cooperate with the Kremlin so the authorities in Warsaw should seize an opportunity to look for common ground whether this be trade, space cooperation, resources imports, African investments, bilateral and multilateral military drills, military sales, common strategic culture, or a comparable stance on Ukraine and Russia. Poland and France have much to offer one to another while Macron’s new term is an ideal opportunity to rebuild bilateral ties.

dr Aleksander Olech, Institute of New Europe

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

_________________________________

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.