THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ON VISEGRAD GROUP COUNTRIES. The aim of the project is to monitor the activities of the PRC in relation to the V4 countries – Poland, Czechia, Hungary and Slovakia. The project is funded by the International Visegrad Fund.

Date: 6 September 2021 Authors: Patrik Szicherle, Lóránt Győri

Wolf warriors against European hawks. Can the European Parliament spearhead EU foreign policy on China?

Recent research on the European Parliament’s party groups’ voting patterns in the European Parliament has revealed that the EP is among the most resilient European institutions when it comes to foreign malign influence. This is especially true in the case of China, which has almost no soft power tools in its arsenal to influence the European decision-makers in the European Parliament. Beijing, even more so than the Kremlin, needs to resort to relations with individual member states on a case-by-case basis to pursue its interests within the EU, which is a highly effective strategy in the eastern part of the EU.

| The research entitled “The specter of authoritarian regimes is haunting the EU” was carried out by a consortium led by Political Capital Institute and supported by the National Endowment for Democracy.[1] Data was compiled on over 90 roll-call votes of the European Parliament to assess individual MEPs and caucuses’ voting behaviour on Russia, China, other authocratic regimes, disinformation and common foreign policy strategies. Each MEP was attributed an index score ranging from 0 to 100 to characterise his or her tendency to vote in favour of foreign authoritarian actors on five indexes created (China-critical index; Kremlin-critical index; Counter-disinformation index; Counter-authoritarian index; Foreign Policy Integration Index), where the higher value means less oppenness to advance authoritarian interests. Indexes were, then, used to identify hidden “voting groups” based on a cluster analysis. |

5 take-aways

- The European Parliament is among the most resilient power-centres of the European Union when it comes to foreign autocratic influence on the European or national levels.

- Based on our results, the EP is the most hawkish European institution. Directly elected MEPs generally critical of authoritarian regimes, including the Kremlin, have a confident majority in the European Parliament.

- However, autocratic power projection is highly dependent on the foreign actors. While the Kremlin can and is relying on its economic, cultural, media, ethnic minority-based influence, beyond its geographical proximity, to project power, China has almost no “soft power” in the EP. It can mostly use its economic leverage to lobby individual member states only.

- Fringe parliamentary groups, the far right Identity and Democracy (ID) and the far-left European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) are the most supportive of authoritarian regimes, as well as most non-attached MEPs.

- Former Eastern Bloc countries still prove to be less resilient to foreign autocratic influence due to historical reasons, such as new and fragile democratic institutional systems, corruption-prone local politicians and oligarchs, strong far-right and/or populist parties with a greater level of Euroscepticism that makes foreign autocracies easy to reach out to local political actors wary of the EU or the Euro-Atlantic Alliance.

The EU has been on a collision course with China for quite some time despite the Union’s inability to formulate a common foreign policy on several issues related to Beijing. In spite of US President Joe Biden urging the leaders of the European Union to form a united, transatlantic front against China to address cybersecurity and the safeguarding of democratic values during the EU-US Summit in June 2021,[2] Europeans have reiterated the need for “strategic autonomy”, while their final statement mentioned China barely.[3] The discord between Western partners was again put on display during the July NATO Summit, where French President Emmanuel Macron stressed that China is not the Alliance’s first priority,[4] standing in stark contrast with the US president, who called it a main “security challenge” to be dealt with.

Still, there are a number of quite recent issues that make China a problem for the European Union’s long-term foreign policy. On a theoretical level, it is hard to reconcile the EU’s New strategic agenda 2019-2024 centred around “protecting citizens and freedoms,”[5] and “promoting European interests and values on the global stage” with China’s reluctance to cooperate on the probe into the pandemic’s origins,[6] the cyberattack of Chinese hackers on Microsoft servers, or Beijing using the export of its COVID-19 vaccines to gain leverage over poor countries in Africa or South America – on top of the human-rights abuses in Hong-Kong or Xinjiang. It is not that the European Union is not responding to these threats, as the EU has joined the White House in its condemnation of the cyberattacks,[7] while High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borelly warned the EU of loosing influence to China over the insufficient shipments of COVID-19 vaccines to Africa and Latin America.[8] Additionally, the EU has already sanctioned Chinese officials involved in Xinjiang’s mass internment policy.

Who will blink first?

The real question is who could and would implement tough policies on China for the longer term in an increasingly difficult situation, when every member state, transatlantic partner and even China is trying to end the twin-crises of the pandemic and the economic downturn in the global production chain. The EU is interested in balanced trade relations to speed up its economic recovery, and China is as much interested in the restoration of its global economic powerhouse, faced with the collapse of Beijing’s global image due to the pandemic.[9] The EU’s Eastern foreign policy, in fact, masks an internal decision-making impasse. In December 2020, the European Commission hammered out the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) deal between the People’s Republic of China and the European Union supported by big member states, particularly Germany, which has the most to gain from it, and the European Council. The deal was, however, held up by the European Parliament, whose members sitting on the subcommittee on human rights were targeted by Chinese countersanctions over the EU’s own punitive measures on four Chinese officials involved in human rights abuses against the Muslim minority in Xinjiang.[10] Beyond the foreign policy differences between EU institutions, individual member states also follow varied approaches to handling Beijing’s increasing assertiveness in the international sphere.

Chinese wolf warriors face EP hawks, but also some friendly eastern member states

Despite internal differences within the EU on how to handle China, our analysis has revealed that the European Parliament holds the upper hand against Beijing both in terms of dMEPs’ shared opinion and even in some areas of legislative power.[11] Whereas the Parliament cannot be considered the strongest power centre in the EU institutional structure in foreign policy, its veto power over trade agreements makes the EP especially effective legislatively against any major economic partner of the bloc.

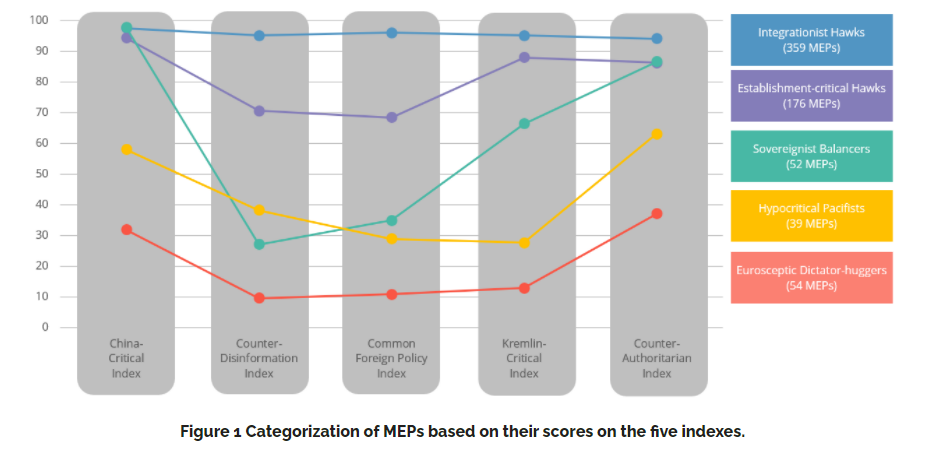

Based on the analysis of over 90 foreign policy-related votes of the Parliament, we could categorise MEPs into five groups according to their score on five authoritarian influence indexes (China-critical Index; Kremlin-critical Index; Counter-disinformation Index; Counter-authoritarian Index; Foreign Policy Integration Index). Most of the MEPs can be considered Integrationist Hawks, who make up 53% of the 680 representatives we could categorize. They do not only support joint action against almost all authoritarian regimes, but back the development of common EU strategies in the fields of disinformation and foreign policy as well – as seen on Figure 1 below.

In the second most significant group we can find Establishment-critical Hawks – mainly from the European Conservatives and Reformists and the Greens (26%) – who would also be in favor of strong action against authoritarian states, but they often express concerns about joint disinformation and foreign policy strategies. Sovereignist Balancers are a much smaller group (8%) than the previous two, including members such as the Italian Lega. They almost completely refuse common EU action against disinformation or joint foreign policy strategies, but are critical of numerous authoritarian regimes, although much less so in the case of Russia, unlike the previous two groups. Hypocritical Pacifists (6%), such as the Austrian FPÖ or the Greek Syriza, do criticize China or other authoritarian states on a case-by-case basis, but are only critical of the Kremlin rarely, while Eurosceptic Dictator-huggers (8%) are unlikely to support any EU action. The latter group is represented, among others, by MEPs from the German AfD and the French National Rally.

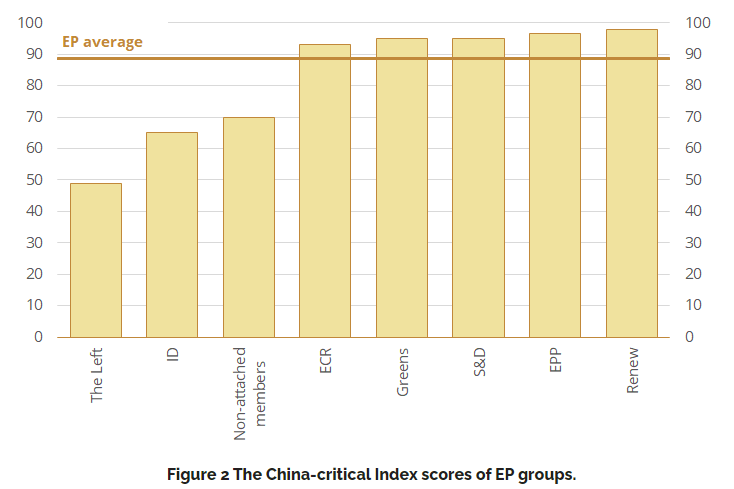

China is almost unanimously criticized by all the large EP caucuses on most key policy issues, such as the situation of the Uyghur in China[12] or the PRC National Security Law for Hong Kong[13]. Beijing’s interests were mainly represented or defended by the far-left The Left caucus, as seen on the second figure below. Numerous populist far-right forces, such as Lega or even an extremist Slovak MEP are critical to China, albeit to varying degrees.

The Left defended China rhetorically by pointing to the EU’s overreach in human rights issues and American “imperialist ambitions.” Meanwhile some populist right-wing or far-right forces, such as the German AfD or the French National Rally, criticized China rhetorically, but abstained when it came to taking action, citing the need for dialogue with Beijing instead of its alienation. This suggest that such forces might see China as a counter-pole to the US- and EU-led western order that they reject. It is worth mentioning that pro-Chinese actors are to be found in other caucuses as well. Such key figure is MEP Jan Zahradil from the Czech ODS (Civic Democratic Party), the lead candidate of the ECR Group in the 2019 European Parliamentary elections. Zahradil has close connections to Chinese actors: he was the chairman of the now-suspended EU-China Friendship Group in the European Parliament. The results of such cordial connections are clear: Zahradil’s China-critical Index score was much lower than that of his ODS colleagues even though national party members usually vote very similarly to each other.

Chinese influence in Central-Eastern Europe

On the national level, Beijing is successfully using a carrot and stick approach in the CEE region to strike individual deals with Central-Eastern European states utilising a combination of hard and “sharp power,” which is a quite effective foreign policy tool, since foreign policy requires unanimous support from EU members. As a result, the EU failed to adopt a statement calling on China to abide by an arbitral tribunal ruling on the South China Sea because of vetoes (allegedly) by Greece, Hungary and Croatia in 2016.[14] Chinese influence based on large-scale deals is especially striking in the case of Hungary. The Hungarian government has awarded the renovation of the Budapest-Belgrade railway worth over HUF 700 billion or EUR 2 billion willingly to a Chinese company as part of the Belt and Road initiative and continues to support Huawei’s role in the installation of 5G technology in the hopes of attracting even more Chinese investment. Hungary even went so far as to finance and build the first Chinese campus in the EU for the Fudan University, which is considered by many a national-security risk on its own. In return, Hungary has blocked multiple EU statements condemning China’s Hong Kong policy in recent months and Fidesz MEPs were among the few voting against the resolution freezing the ratification of the CAI in the EP.[15] However, pushing for Chinese interests is not something only done by the bloc’s poorer states: Germany was the main power pushing for the EU-China investment deal,[16] which – not accidentally – is the state standing the most to gain from it.

China has successfully cultivated the image that it invests or prefers to invest in countries that do not follow policies against its interests or step over its red lines concerning Taiwan, Hong Kong, or human rights issues. Case in point: Chinese diplomacy publicly thanked the “relevant” member state for “upholding the correct position” after yet another Greek EU veto concerning China in 2017.[17] Of course, when economic leverage is not working, like in the Czech Republic, relation can sour quickly over human rights issues or Taiwan, even to the point of Chinese officials outright threatening Czech diplomats with “consequences.”[18] Naturally, the Czech example proves that Beijing lacks the full spectrum of foreign policy instruments to influence decision-making on the European level, unlike Russia, which is waging a proper hybrid war against Ukraine and the EU.

Still, the overwhelming majority’s reluctance to view Beijing or EU-China issues favourably severely limits China’s capability to have a favourable image or influence decisions in the European Parliament based on “soft power.” Our data has revealed that Chinese influence must rely mostly on individual, state-level lobbying efforts. They can mainly try to influence national governments, whose representatives sit and vote in the Council, through the use of China’s immense economic leverage to promise lucrative investments to individual states.

How does the Kremlin differ?

The Kremlin’s situation is somewhat different. First, the Russian regime can rely on the open support of the majority of both the far left and the far right in the EP, as well as that of some mainstream political forces in certain cases. For instance, the vast majority of the rhetorically Kremlin-critical and pro-sanctions CDU-CSU and ÖVP MEPs struck down calls to halt the Nord Stream 2 project immediately on multiple occasions. Meanwhile, the French Lés Republicains became increasinly favorable to Russia over time. While the Kremlin is ideologically closest to the far right, it has been highly successful in cultivating the image that it is an economic, political and military superpower, which also allows for the Putin regime’s portrayal as a crucial pillar in a multipolar world order. This success could also convince mainstream political parties to argue for “resetting” relations with Russia. Besides its raw energy materials and successful sharp power efforts in the information space, Moscow can also continue exploiting its communist-era networks: the Bulgarian Socialist Party, for instance, the successor of Bulgaria’s communist-era rulers, consistently refuse to vote against the Kremlin’s interests. Thus, the Putin regime, while it still faces considerable challenges in influencing European political decisions, is better equipped to influence policy-making within the EU both on the supranational level and in individual member states.

Not all is lost

Despite significant efforts by authoritarian states, particularly Russia and China, to influence European decision-making, the results of these efforts are limited, proving that the EU as a whole is more resilient against authoritarian influence than the sum of its parts. While numerous China-critical EU statements have been vetoed, the Union did levy sanctions on four Chinese officials for their role in Xinjiang, much to the displeasure of Beijing.[19] Sanctions on Russia have been in place since 2014 despite multiple countries threatening to bring them down.[20] Naturally, the frequent criticism of EU sanctions by some regimes, such as Hungary[21] do limit EU action: European bureaucrats will not propose policies that are certain to be rejected, such as strengthening economic sanctions on Russia or expanding the list of sanctioned Chinese officials – a win for Moscow and Beijing.

Thus, while EU foreign policy has not been as ineffective as many have claimed, the situation could be improved, among others, by moving away from unanimous decisions in the Foreign Affairs Council at least on a limited number of issues, which is certainly going to be a point of debate at the Conference on the Future of Europe. This might help the EU become a more significant actor on the global scene and give more weight to the foreign policy recommendations of the EU’s only directly elected body, the European Parliament.

[1] Péter Krekó, Szicherle, Patrik, and Molnár, Csaba, ‘Authoritarian Shadows in the European Union’ (Political Capital Institute, 2021), https://www.politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/authoritarian_shadows_in_the_eu_2020_09.pdf.

[2] ‘EU-US Summit, Brussels, 15 June 2021’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-summit/2021/06/15/.

[3] ‘EU-US Summit 2021 – Statement’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/50758/eu-us-summit-joint-statement-15-june-final-final.pdf.

[4] ‘NATO Needs to Know Who Its Enemies Are, Says Macron | Reuters’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/nato-needs-know-who-its-enemies-are-says-macron-2021-06-10/.

[5] ‘EU Strategic Agenda for 2019-2024’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/eu-strategic-agenda-2019-2024.

[6] ‘China Hits Back after EU Official Joins Call for Cooperation on Pandemic Origins Probe’, POLITICO, 28 July 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/china-hits-back-after-eu-official-joins-call-for-cooperation-on-pandemic-origins-probe/.

[7] ‘China: Declaration by the High Representative on Behalf of the European Union Urging Chinese Authorities to Take Action against Malicious Cyber Activities Undertaken from Its Territory’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/07/19/declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-eu-urging-china-to-take-action-against-malicious-cyber-activities-undertaken-from-its-territory/.

[8] ‘Borrell: EU’s “Insufficient” Vaccine Donations Open Door for China’, POLITICO, 30 July 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/josep-borrell-eu-vaccine-donations-insufficient/.

[9] Laura Silver, Kat Devlin, and Christine Huang, ‘Unfavorable Views of China Reach Historic Highs in Many Countries’, Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project (blog), 6 October 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/10/06/unfavorable-views-of-china-reach-historic-highs-in-many-countries/.

[10] ‘China Throws EU Trade Deal to the Wolf Warriors’, POLITICO, 22 March 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/china-throws-eu-trade-deal-to-the-wolf-warriors-sanctions-investment-pact/.

[11] Krekó, Szicherle, Patrik, and Molnár, Csaba, ‘Authoritarian Shadows in the European Union’.

[12] ‘Debates – Situation of the Uyghur in China (China-Cables) (Debate) – Wednesday, 18 December 2019’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2019-12-18-ITM-019_EN.html.

[13] ‘Texts Adopted – The PRC National Security Law for Hong Kong and the Need for the EU to Defend Hong Kong’s High Degree of Autonomy – Friday, 19 June 2020’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0174_EN.html.

[14] Georgi Gotev, ‘EU Unable to Adopt Statement Upholding South China Sea Ruling’, Www.Euractiv.Com (blog), 14 July 2016, https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/eu-unable-to-adopt-statement-upholding-south-china-sea-ruling/.

[15] ‘MEPs Refuse Any Agreement with China Whilst Sanctions Are in Place | News | European Parliament’, 20 May 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210517IPR04123/meps-refuse-any-agreement-with-china-whilst-sanctions-are-in-place.

[16] ‘Merkel Pushes EU-China Investment Deal over the Finish Line despite Criticism’, POLITICO, 29 December 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-china-investment-deal-angela-merkel-pushes-finish-line-despite-criticism/.

[17] ‘Greece Blocks EU Statement on China Human Rights at U.N.’, Reuters, 18 June 2017, sec. China, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-un-rights-idUSKBN1990FP.

[18] Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com), ‘China Warns Czech Leaders Will Pay “heavy Price” for Taiwan Visit | DW | 31.08.2020’, DW.COM, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/czech-china-taiwan/a-54764477.

[19] ‘Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Announces Sanctions on Relevant EU Entities and Personnel’, accessed 24 August 2021, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1863106.shtml.

[20] ‘Salvini: Italy “Not Afraid” to Use EU Veto to Lift Russian Sanctions’, POLITICO, 16 July 2018, https://www.politico.eu/article/matteo-salvini-italy-not-afraid-to-use-eu-veto-to-lift-russian-sanctions-crimea-vladimir-putin/.

[21] -Justin Spike, ‘Citing Losses in the Billions, Hungary Foreign Minister Urges Lifting of Sanctions against Russia’, The Budapest Beacon, 24 January 2017, https://budapestbeacon.com/citing-losses-in-the-billions-hungary-foreign-minister-urges-lifting-of-sanctions-against-russia/.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission. Support

ResztaTekstu2

This article is a part of the project “The Role and Influence of the People’s Republic of China on Visegrad Group Countries” funded by the International Visegrad Fund.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.