NEWS

Date: 25 April 2019Author: Mateusz Kubiak

U.S. Challenge in the Arctic

In recent weeks, Russia has issued a set of declarations, all of which merely confirmed the Kremlin’s intentions for the Arctic region. Of course, Moscow’s activity remains under the close watch of Washington whose officials are now finalizing the U.S. national strategy for the Arctic. The United States needs to focus its attention both on Russia and China, the latter of which has increasingly emphasized its presence in the Arctic.

So far, much has been said about the geopolitical and economic importance of the Arctic; it, however, seems that competition over the region has entered upon an entirely new stage. This is mainly because of an ever-increasing pace of climate change, the development of mining and transport technologies or the emergence of China as a new key player in the area. In consequence, the Arctic game, played between the above countries, is gaining momentum while not necessarily focusing on the military factor, despite the Kremlin’s showy presence in the neighborhood. The issue at stake here is gaining control over natural resources and shipping lanes as well as establishing the division of the disputed maritime zones.

Russian ambitions

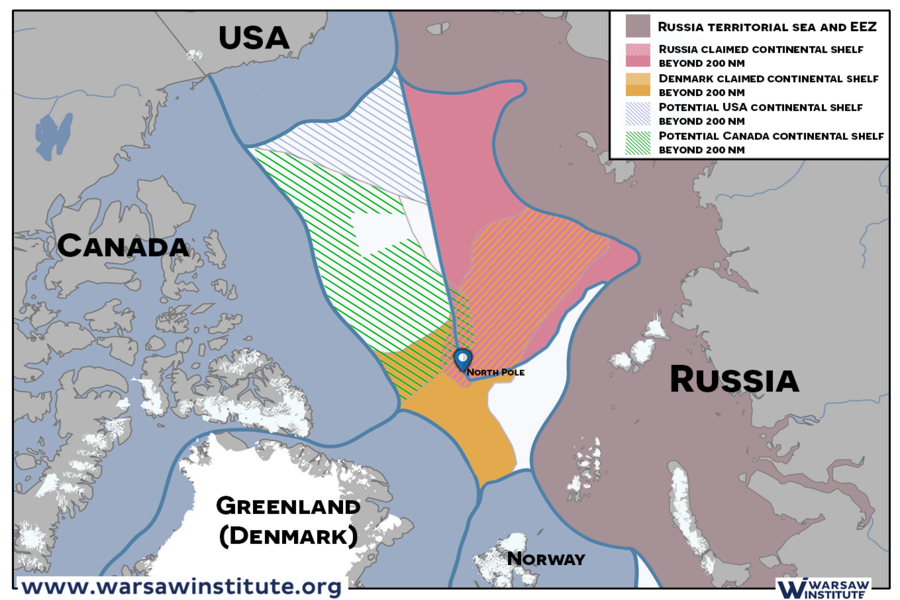

Russia, which has put forward objectives for the Arctic, has the longest coastline along the Arctic Ocean and has submitted territorial claims to the largest part of the Arctic’s continental shelf, along with the North Pole. Importantly, the five coastal states bordering on the Arctic Ocean (Russia, the United States, Canada, Denmark, and Norway) have not yet marked a clear distinction of the Arctic waters. However, of all countries, Russia is at the most advanced stage of proceeding its application to the appropriate UN commission. In early April, the commission announced that Russia’s Arctic shelf claims can be geologically justified, as a result of which Moscow expects the United Nations to issue a favorable verdict by the end of the year.

This coincided with a set of declarations made in the first week of April by Russian President Vladimir Putin and a group of officials and managers holding ties to the domestic oil and gas sector. Their proposals include among others a major concept of the Northern Sea Route, described as a key shipping corridor along Russia’s Arctic coast. Moscow has expressed hopes that thanks to the shrinking polar ice in the Arctic region, the Route will become a fully competitive alternative to the Suez Canal, shortening maritime shipping between the West and Asia by up to one-third. This seems to explain Putin’s goals for the amount of cargo carried across the shipping lane to grow to 80 million tons by 2025, from the present-day 16,5 million tons. As a result, Moscow would be awarded a political dividend, under which it could be empowered to implement regulations limiting international freedom of navigation while giving it the greatest possible control over the Arctic freight. Also, the Northern Sea Route would be viewed as the main channel for transporting energy resources. As reported, Russian Novatek is soon expected to annually produce in the Arctic at least tens of millions of liquefied natural gas (LNG), compared to 20 million tonnes per year, while state-run Rosneft has announced its plans to build new oil clusters to secure the annual output of up to 100 million tons of crude oil.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

Chinese activity

China seems to be driven by similar motivations as those expressed by Russia; although Beijing, which seeks to draw advantages from newly launched shipping lanes and Arctic’s natural resources, formally has no access to the region, it aspires to join the “Arctic club.” This was marked by China’s first white paper to contain a national strategy for the Arctic. Published at the beginning of the last year, the document comprised the region as part of China’s New Silk Road concept to link Beijing with the West, while announcing the need to encourage investments and establishing China’s identity of a “near-Arctic state.”

China has been committed to developing its Arctic fleet, already having surpassed the United States in terms of a number of its ice-breaking ships and has also announced its intention to build own nuclear-powered icebreakers. Until now, Russia has been the only country to have such vessels. China’s naval ambitions are accompanied by investments, either already realized or attempted on Arctic soil. Beijing holds a 29.9-percent stake in Russia’s Yamal LNG facility while negotiations on China’s participation in Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 project are currently underway. Interestingly enough, China has carried out activities in relation to Iceland and, more importantly, also to Greenland, the latter of which is viewed by Beijing as an emerging source of natural resources, including uranium, rare metals and also oil and gas, a strategic place where it has already bankrolled a number of mining or infrastructure projects.

Is it time for U.S. reaction?

Russian and Chinese presence in the Arctic stands in stark contrast to the U.S. one, seen as developed to a lesser extent. Also, Washington has in its inventory only two fully operational ice-breaking vessels, which is twenty times less than Moscow, nor does it dispose of a deepwater port. In addition, despite the U.S. Extended Continental Shelf program, the American administration is incapable of submitting an application to recognize their claims to the Arctic shelf as Washington is not a party to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Given all the aforementioned conditions, it is yet not surprising that U.S. experts and military call for expanding Washington’s potential in the Arctic. A wider debate is expected to ensue as a result of the latest U.S. strategy for the Arctic, imposed by the U.S. Congress and scheduled to be published later this year. If to take into account statements made by the U.S. administration, the document will be a response to Russian and Chinese expansion in the Arctic, with particular emphasis on the activities of the latter country. This deems to be necessary, though, especially given the fact that the Arctic’s geopolitical potential may be successfully used by the two above actors.

This article was originally published at “Dziennik Związkowy”