THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 4 November 2019 Author: Robert Rajczyk

Hong Kong and Macau: The Paradoxes of Autonomy

Macau and Hong Kong are former European colonies in Southeast Asia. Both territories have held the status of the special administrative regions under Chinese sovereignty since 1999 and 1997, respectively. This means that, except for their foreign and defense policies, they are self-governing bodies, albeit on the blessing of Beijing.

Macau, a former Portuguese colony, is famous for the tourism and entertainment industry, while Hong Kong, which in the past remained under British rule, boasts the reputation of one of the world’s top financial centers. In Hong Kong, people take to the streets to demonstrate, contrary to neighboring Macau that is not beset with a comparable problem at all. Some Chinese nationals from mainland China pump money into the gambling industry, the sole place in China where casinos are legal. Macau’s local authorities implemented mandatory patriotic education in schools and made a decision to bar non-Chinese judges from any cases involving national security issues[1]. Macau people take part in the elections less willingly than their Hong Kongese peers, while Portugal –– since it toppled the dictatorship in the Carnation Revolution of 1974 –– made it clear it was doing nothing but just administering the Chinese territory that came under the profound influence of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

June 30, 1997. At dawn, according to tradition, the British flag of Hong Kong is hoisted atop a pole right in front of the governor’s residence. Chris Patten, who serves as the 28th governor of Hong Kong, goes around the square with the pole on it for the last time in this role. Starting tomorrow, his duties will be assumed by the Chief Executive, newly appointed by Beijing, while across the Admiralty district of Hong Kong flags of the People’s Republic of China will flutter and a new banner of an already-Chinese Hong Kong. Illustrated as a symbol of the local population, the banner –– modeled on the Chinese one –– features a Bauhinia flower with the five red stars found on each of the petals. On July 1, 1997, Chris Patten, accompanied by Charles, Prince of Wales, and heir apparent to the British throne, who came to the handover ceremony on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II, sails away from the city on the royal yacht Britannia as the “Rule, Britannia!” anthem is playing in the background –– ending 156 years of British rule in the territory.

130 000 people joined the parade organized by The Civil Human Rights Front to oppose the proposed extradition law amendment, which would allow China to extradite persons in Hong Kong for alleged violation of China’s laws. Hong Kong SAR, April 28, 2019. fot. Flickr.com/etan liam

130 000 people joined the parade organized by The Civil Human Rights Front to oppose the proposed extradition law amendment, which would allow China to extradite persons in Hong Kong for alleged violation of China’s laws. Hong Kong SAR, April 28, 2019. fot. Flickr.com/etan liamIn the language of its indigenous population, the name “Hong Kong” means “fragrant harbor”. But for every subsequent empire that held the city in its clutches, it had a slightly different scent. For the British, the aroma was a hint of its colonial superpower status and an exotic overseas colony, though, for the People’s Republic of China, it has been malodor of rebellion. Over the past twenty years of Beijing’s dominance over Hong Kong, its residents have yet again taken to the streets to protest, each time seeking to preserve the city as a stronghold of democracy. Protests that swept across Hong Kong in 2012, 2014, and 2019 have always been politically motivated. The first rally sparked off against a proposed curriculum that embraced political features of mainland China. The second of which, often called the Umbrella Revolution, was intended to address the Hong Kong local electoral system, imposed by Beijing. This year’s rally, culminating with nearly 2 million residents having flooded to the streets on June 9 (considering that Hong Kong has a population of 7.4 million people), is the climactic expression of disapproval of the pro-Chinese administration’s efforts to put forward a proposed amendment on an extradition law, seen by some as a measure to crack down on uncomfortable political opponents. And the number of these is still growing in the Pearl River harbor.

NEWSLETTER

The Umbrella Movement, named after the umbrellas that shielded demonstrators from the hot sun, had brought to local power some candidates that stood up to defend universal suffrage, a solution agreed on with the United Kingdom[2]. The Chief Executive of Hong Kong –– being equivalent to the post of a Prime Minister elsewhere –– takes their oath to the Chinese authorities and is chosen by Hong Kong residents out of other candidates approved by the Communist Party of China[3].

Umbrella Revolution, Hong Kong October 2, 2014. fot. Flickr.com/L.Rico

Umbrella Revolution, Hong Kong October 2, 2014. fot. Flickr.com/L.RicoEarlier, the governor arrived from London abroad a British Airways jet –– as the nominee of the British monarch –– while any plausible discussions over their candidacy took place inside the UK’s Foreign Office, far from the colony’s inhabitants. Notwithstanding this, no one seemed to complain about a lack of consultation as the United Kingdom stimulated an unfettered development –– based on the freedom of expression and remaining democratic values –– of the Kowloon Peninsula, Hong Kong island, and the New Territories. Owing to such efforts, ‘the fragrant harbor’ has become one of the Four Asian Tigers; countries that boast the world’s largest number of buildings higher than 150 meters and a GDP per capita five times higher than Poland’s. It served the role of a bridge between communist China on the one hand, and the democratic West on the other.

The situation started to change in the late 20th century. To mark the CPC’s centenary in 2021, China, which has begun to gather stream while assuming worldwide importance, has considered it a matter of honor to unify all Chinese lands seized by foreign forces back in the 19th century. Back then, a “one country, two systems” formula emerged, originally developed, however, with Taiwan in mind. The years 1984 and 1987 saw, for their turn, declarations signed with Great Britain and Portugal to hand over these two colonies back to China. This took place on July 1, 1997, and December 20, 1999. Under Hong Kong’s and Macau’s basic laws, or their constitutional documents, adopted by the National People’s Congress (NPC), both colonies were provided guarantees for maintaining their autonomy for a half of century, except for their foreign and defense policies. The first fifteen years did not indicate any changes were to take place sometime soon.

After Xi Jinping rose to power in Beijing, the situation saw a tilt towards his longed-for policy of “a great renaissance of the Chinese nation”, intended to happen through, inter alia, establishing China’s Social Credit System; a mechanism that aimed to foster social ties once completely swept away by the cultural revolution. But what stands out as its key factor is an ambition to shape Chinese prosperity, with the strategy of both increasing China’s domestic consumption and exporting surpluses. The latter could materialize owing to the Belt and Road initiative. This political and economic project designed to strengthen and expand China’s zone of economic influence worldwide has also particular focus on Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans (as part of the 16+1 format), as well as, first and foremost, Africa.

Xi Jingping, for whom it is evidently politically inconvenient to pursue Deng Xiaoping’s idea of collective leadership, remains increasingly committed to solidifying his political position. What rose as the culmination of Xi’s deviation from the principle, formulated in an effort to prevent the emergence of a Mao Zedong-like dictatorship, was a 2018 constitutional amendment removing term limits for the chairman of the Communist Party of China, or the de facto state’s president. During a six-year rule that preceded the constitutional amendment, Xi purged all opposition within the party under the guise of an anti-corruption campaign, a fight whose origins date back to the time of the Chinese Empire and the founding of China’s first republic[4]. Struggle against corruption has even become a theme of a popular Chinese TV drama series ‘In the Name of the People’, to a great extent bankrolled by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

It would be yet a mistake to believe that the process of consolidating power in the hands of one man is coming to an end. After all, the Communist Party of China has a total of more than 90 million members. With such a sizeable membership, the Communist Party of China is not an undivided monolith, and tensions running high between its numerous factions do resemble Western-like inter-party rivalries. There are also worried voices of dismay, mainly from the former party and state leaders, stressing that Xi had made a considerable mistake, both political and economic, upon declaring a trade war with the United States. Xi Jinping’s actions can be also interpreted as sailing away from Deng Xiaoping’s “28-Character Strategy”. This boils down to China’s pursuit to consolidate its power as a state as well as strengthening the projection of its power on the global scale, revealing neither efforts nor the state’s intentions in this regard. Conspicuously enough, attesting to such is also the willingness to dispute assertively the Spratly Islands, an archipelago in the South China Sea where China operates according to fait accompli tactics.

Hong Kong’s “troubles” do not serve Xi Jinping’s image that has been shaped over the past recent years, depicting him as a capable politician and a global statesman. How the issue should be tackled is in effect a ‘litmus test’ for Xi Jinping’s leadership while serving as an occasion to secure support from “hard-headed” communists in the twenty five-member Central Politburo of the Communist Party of China, of whom seven people hold posts in the Politburo Standing Committee, or an executive committee.

A certain paradox is that Hong Kong’s autonomy has become “a pain in the neck”, but mostly for some of China’s senior policymakers. Mainland Chinese, for their part, seem satisfied with all the benefits offered by the special autonomous region. As many as 28 million tourists, or 75 percent of all visitors, leave a lot of money in the city in a move that yet gives a headache to its residents. Tourists’ conduct stands in stark contrast to local traditions, as shows the example of their behavior in public places[5]. Moreover, mainland Chinese individuals and entities invest in the real estate market, a move that has contributed significantly to skyrocketing the already-high prices, shattering most of the inhabitants’ dreams of an own apartment and making it a far more distant dream than that at the time under the British rule. Furthermore, mainland Chinese women on enormous scales decide to go to Hong Kong to give birth to their new-born infants, which is not only due to the infant mortality rate being six times lower than in China, but – first and foremost – it also paves the baby’s way for being granted resident status with the right of free 12-year education or to hold a Hong Kongese passport whose power –– counted as an index according to the number of countries it can access without an visa in advance –– is much greater than China’s[6].

Umbrella Revolution, Hong Kong October 2, 2014. Fot. Flickr.com/Studio Incendo

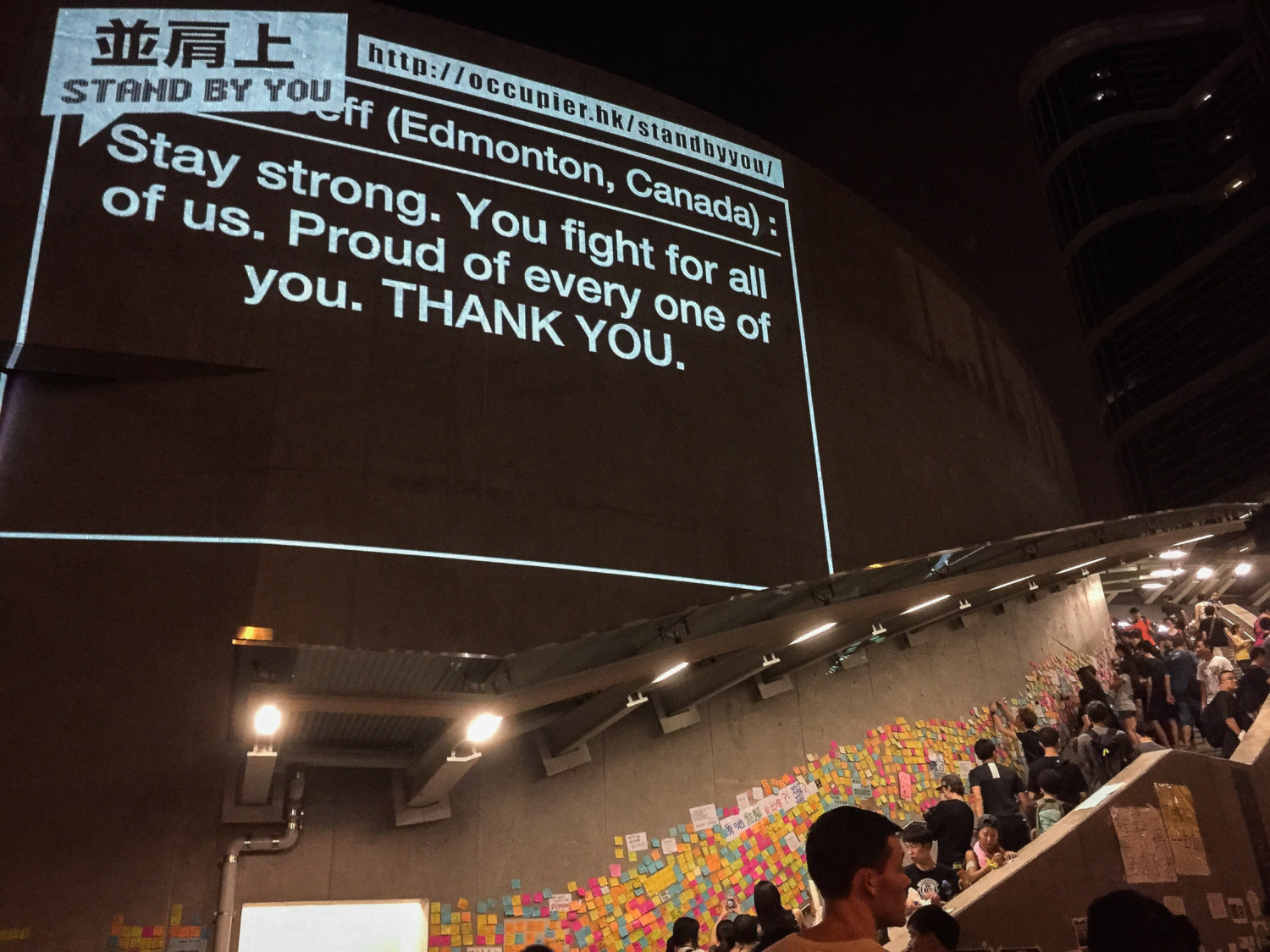

Umbrella Revolution, Hong Kong October 2, 2014. Fot. Flickr.com/Studio IncendoHong Kong residents differ from their mainland peers. While people living in the harbor on the Pearl River generally speak Cantonese, those inhabiting other parts of China communicate in Mandarin. A mere 3 percent of Hong Kong residents feel Chinese, and a social study shows two-thirds of the local population identifying themselves with regional identity. Mandatory patriotic education was implemented to the school curriculum in a bid to reverse this tendency. And then appeared a teenage activist Joshua Wong who, through Internet communication channels, called on his peers to boycott the class. The form in which local rallies are being held keeps evolving, from the initial boycott of a controversial school class, through blockading of the city’s Central business district and its commercial arteries, to rallies whose atmosphere is sometimes far from peaceful. Protestors vandalized the Chinese government’s liaison office and earlier had stormed the Legislative Council, causing damage in its headquarters. Police’s pursuits for quelling the riots, alongside sentencing leaders of the 2014 Umbrella Movement, including Wong, to prison terms of up to a few months, drifted demonstrators away from their former strategy, pushing for a new one instead[7].

Firstly, it is worth noting that there is no strict leadership, while demonstrators who decide to speak with the media cover their faces with sunglasses and surgical masks. In shops where demonstrators buy helmets, protective clothing, and protective foil against pepper gas used by the police, they pay in cash. Also, they managed to develop their own gesture-based system of visual communication, used when in the crowd. The protests further moved to Hong Kong’s international airport in an attempt to arouse the interest of foreigners in the fate of the city under the Chinese rule, at times in a very much insistent manner. Hong Kong demonstrators block subway trains, persistently pressing the emergency button on board, causing delays. Two months of protests going on in Hong Kong worsened the daily life of the city’s residents dramatically. In an interview for a Hong Kong-based daily South China Morning Post, Singaporean real estate agents said that the number of Hong Kong residents people interested in purchasing real estate in the Lion City had risen by one-third over the past eight weeks.

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

But the authorities do not give the game away and have no intention to neglect the problem, possibly inspiring local thugs, labeled “titushky”, to come to the fore. These are members of local gangs who stormed both commuters and young people dressed in black, or the color adopted by demonstrators, at a subway station. Interestingly, they all wear white. China’s “screw-tightening” efforts in Hong Kong has de facto been going on since 2010. City-based editors are grappling with mounting pressure from local administration while their journalists sometimes fall victim to physical assaults by “unknown perpetrators”. Newspaper owners either sell them to more agreeable entrepreneurs or hire journalists that prove more prone to apply self-censorship than their colleagues, accustomed to freedom of expression standards at work. Neither do followers of Falun Gong lead an uneasy life, though –– compared to what takes place in mainland China –– they are not persecuted in any way. Printing books that are forbidden in other Chinese regions is possible in Hong Kong – but may be burdened with consequences. Four years ago, a group of Hong Kong booksellers who sold publications eyed by mainland China as “subversive” suddenly disappeared. They were “accidentally” found in China after only a few months later and publicly repented of their earlier activities.

Beijing sees Hong Kong as an ungrateful child that is unable to distinguish all efforts made by its mighty guardian. Hong Kong’s local financial elites, including those that settled in the city in the post-1997 period, show gratitude to Beijing for being capable of enriching themselves by getting access to the Chinese market. Efforts are also being taken to gravitate the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau closer to mainland China. Part of a train station located in the downtown area, linked with mainland China by a high-speed train, was incorporated into China while the two territories received a link to the continent through a 45 kilometer-long road bridge, a solution that shortened travel time between Hong Kong and Macau, which were previously mostly connected by ferry. Dubbed until recently a bridge between the worldwide economy and a developing China, Hong Kong is losing its current position gradually. Though the city remains a world’s leading financial center, it accounts for a mere 3 percent of China’s GDP. Located nearby and referred to as one of the world’s biggest ports, Shenzhen and Shanghai –– with their stock exchange –– have in fact taken its dominant position. In their pursuit of attracting investors, Chinese firms have in the past moved their premises to Hong Kong. Now it serves as a place from where international companies are doing their best to make an entry into the Chinese market. A World Bank ranking showed that in Hong Kong, it is twenty times as easier to do business than in mainland China.

Hong Kong’s worsening social and political situation has prompted young people, of whom a majority of protesters do not remember life under the British rule, to emigrate to democratically-led Taiwan, whose leader has offered asylum to Hong Kong protestors, yet ignoring China’s law pertaining to ‘no asylum’. The events taking place in close vicinity to Hong Kong are for some Taiwanese –– who do not display a particular pro-Chinese leaning –– evidence of the ‘one country, two systems’ formula’s practical dimension while sending worldwide a signal of how peculiar China’s attitude is to fulfilling international obligations. A spokesperson for Beijing-based Ministry of Foreign Affairs referred to the Sino-British handover deal of 1984 as “a historical document that no longer had any practical significance”. Therefore it is not known whether the ‘one country, two systems’ principle will remain in force after Hong Kong’s autonomy expires in 2047, as stipulated under the Chinese-British agreement, or it is gradually ceasing to be in force through the use of “salami-slicing tactics”, that is; eliminating Hong Kong’s autonomous status, piece by piece.

Moreover, it is not farfetched to argue that limited but worrying resemblances between Tiananmen and the developing situation in Hong Kong could be inferred. At the least, some lessons learnt are worth scrutinizing, albeit taking into consideration the different contexts, hindsight, times, and so on.

Pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong is held by a policeman during a confrontation after taking part in a march towards the West Kowloon rail terminal against the proposed extradition bill in Hong Kong, July 7, 2019. fot. VIVEK PRAKASH/AFP/East News

Pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong is held by a policeman during a confrontation after taking part in a march towards the West Kowloon rail terminal against the proposed extradition bill in Hong Kong, July 7, 2019. fot. VIVEK PRAKASH/AFP/East NewsThe first similarity is the expansion of participating protesters, and with them, a larger list of demands. In 1989, peaceful student-led call for democracy spread to other cities of China, running the risk of destabilizing the political system. In 2019, the first Hong Kong protesters stood against the extradition bill, yet have since also again demanded democracy, even references to secession. One ought to wonder how this rings in the ears of the CPC members, which staunchly emphasizes on the country’s unity.

The second similarity is a half-hearted attempt to meet protesters expectations. These are met with an increasingly stern warnings from the CPC. Chief spokesman for the Chinese Ministry of National Defense Wu Qian said that Hong Kong rallies “absolutely cannot be accepted”, hinting the possibility of a military intervention by a Chinese garrison, already on the spot, especially given that the constitution of the Special Autonomous Region allows Hong Kong’s leaders to submit such a request to Beijing officials. In his remarks, Mr. Qian added that the demonstrators “have invited the wolf into their home, and their actions are orchestrated by foreign-based anti-Chinese forces”.

The third similarity is timing close to a significant date. In May 1989, where protests are already a month long, Mikhail Gorbachev visited Beijing. Such a state visit was the first in 3 decades, normalizing relations after the Sino-Soviet split. With a state visit come several journalists, which then exposed the protests and caused embarrassment. Surely no one expected a military crackdown close to October 1, 2019 for the same reason that it would not look too good. Whilst that date has passed, media attention on Hong Kong has not.

The fourth key similarity, and perhaps the most worrisome, is the accusation by the CPC that the protests are not authentic expressions of disapproval of genuine problems, but the works of foreign intelligence agencies seeking to discredit the CPC. They referred to this as ‘black hands’ in 1989, and they did so again in 2019.

Before the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests unfolded, little had indicated the possibility of military intervention. In May 1989, martial law was declared, and in June 1989, the military moved in. A plausible military intrusion in Hong Kong would, in turn, call up a clear association with the 1989 events. Hence, what stands out as a far more plausible scenario, however, is responding to the crisis with a range of political tools, though it cannot be ruled out that Beijing will react forcefully in the case of the tensions running high and getting out of control of law enforcement agents who are already using tear gas and rubber bullets to quell the groups of protestors. Perhaps the Hong Kong police will soon get help from the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force –– or mainland China’s riot police –– as after all, both them are carrying out joint drills in the Canton region, just across the border.

Intriguingly, developments in Hong Kong also pose a PR problem for the democratic-leaning West, as well as European firms that are present there. Perhaps a solution to Hong Kong’s hardships would be political independence, modeled on the Baltic States close to the demise of the Soviet Union. Back then, there were no indications that the mighty power would allow three of its republics to detach with virtually no bloodshed, except for, unfortunately, tragic events at the foot of the Vilnius TV tower. Because honor, and “saving face”, is known to be of crucial importance for hierarchical customs associated with cultures in East Asia, deploying mainland militia to quell pro-democratic protests is not such a PR catastrophe as engaging troops. An intervention of Chinese police officers could be depicted through the lens of propaganda as a regular action taken in a bid to restore public order.

However, what counts most in the case of Chinese communists is a message on the party’s effectiveness and its unquestionable leadership. After all, this is why Beijing is so touchy about Taiwan’s independence and U.S. aid there. If there is a solution to the ongoing conundrum in Hong Kong to attain Beijing’s agreement, it likely will have to allow Beijing to ‘save face’, at the very least, domestically, where a policy envisioning a unified China is dogmatically pursued.

[1] Based on Portuguese law, Macau’s jurisdiction allows judges of foreign origin to be appointed.

[2] On the tide of rallies, there emerged political parties seeking to advance autonomous – or even secessionist – slogans. However, a few Hong Kong’s Legislative Council deputies lost their seats under a decision of a local court in the aftermath of their refusal to take an oath of allegiance to China.

[3] Macau’s local government structure is headed by the Chief Executive, who is appointed by China’s central government after getting a green light from a committee that consists of members endorsed by social organizations. The Legislative Assembly is a body comprising both directly elected legislators while other members are elected in indirect suffrage and appointed by the head of administration.

[4] The period between 1911 and 1949.

[5] It is about breaching the ban on eating in the Hong Kong subway or satisfying the youngest children’s physiological needs on the sidewalks.

[6] https://www.passportindex.org/comparebyPassport.php

[7] Three leaders, among whom Wong, 20, were sentenced to from 8 to 10 months in prison, yet not for taking part in the protests but de facto for hooliganism, which made them first-ever political prisoners in China’s Hong Kong.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.