SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 14 December 2018

Russian Policy Towards the Arctic

- Russia under Vladimir Putin regards the Arctic as a strategically important region whose assets may make it play a key role.

- From Russia’s perspective, all ongoing climate changes “pave the way” for the development of shipping and profitable exploitation of energy resources in the Arctic region, though, due to the melting permafrost, they may pose a threat to the local land infrastructure.

- Simultaneously, there takes place Russia’s unprecedented militarization of the Arctic that may allow Moscow to act unilaterally in the event of any further erosion of international order, also regarding reinforced claims for the Arctic continental shelf.

SOURCE: KREMLIN.RU

SOURCE: KREMLIN.RU

Russia’s activity in the Arctic cannot pass for a completely new phenomenon, and while it is a subject of sensational press reports, Moscow has for many years developed its presence in the region. The entire process coincides with the events that took place in 2018 when Russia reached the record-breaking level of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) shipping and continued the development of its military potential while a state-run gas company Novatek announced the opening of new LNG (liquefied natural gas) production lines. All the events may therefore lead to a wider reflection on the scope of Moscow’s activities in the region.

Arctic legal status

Geographically, the Arctic is usually defined as the area around the North Pole, bounded either by a line known as the Arctic Circle or the 10 degrees Celsius isotherm. It thus comprises the Arctic Ocean area and the northernmost territories of five coastal states (Russia, Canada, the USA, Denmark, and Norway) that are entitled to claim the rights to Arctic waters under the provisions of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). At the same time, these claims are partly contradictory while the Arctic Ocean’s legal status remains unregulated.

Attempts to reach an agreement on the Arctic’s legal regime have been made since the 1920s, yet they have not delivered any definite results. However, the Ilulissat Declaration, signed in 2008 by the “Arctic Five” (five coastal states), passes for an essential reference point for further discussions on the area’s legal status. The parties to the agreement jointly agreed that there had been no justification to introduce completely new legal solutions regarding both the Arctic region and the need to apply the existing principles of the law of the sea. All the commitments were reaffirmed in May this year, marking the tenth anniversary of the declaration.

As a result, all coastal states established exclusive economic zones (EEZ) covering up to 200 nautical miles that gave them the right to make any decisions on the extraction of natural resources. All international disputes in the area derive from at the further development of the EEZ of a 200-nautical miles stretch as long as the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) would adjudicate, based on some previous geological expertise, that this area constitutes a natural extension of the continental shelf of a given country. Such demands are thus raised by the Arctic states, including Russia as the country submits territorial claims to the underwater Lomonosov Bridge which passes through the North Pole[1].

Russia’s regional perception

Russia’s perception of the Arctic refers both to the state’s land territory located north to the Arctic Circle (2.2 million km2, inhabited by up to 3 million people) as well as to the Arctic Ocean itself. In both cases, it becomes clear that these areas are of particular interest for the Kremlin as the Russian authorities keep additionally bolster the ongoing climate changes that are increasingly “opening” the Arctic region to all kinds of human activity. According to the latest research carried out by the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center, the sea ice coverage has dropped by about 30 percent in the last 40 years while some experts argue that in the upcoming decades the Arctic Ocean may periodically become an ice-free reservoir.

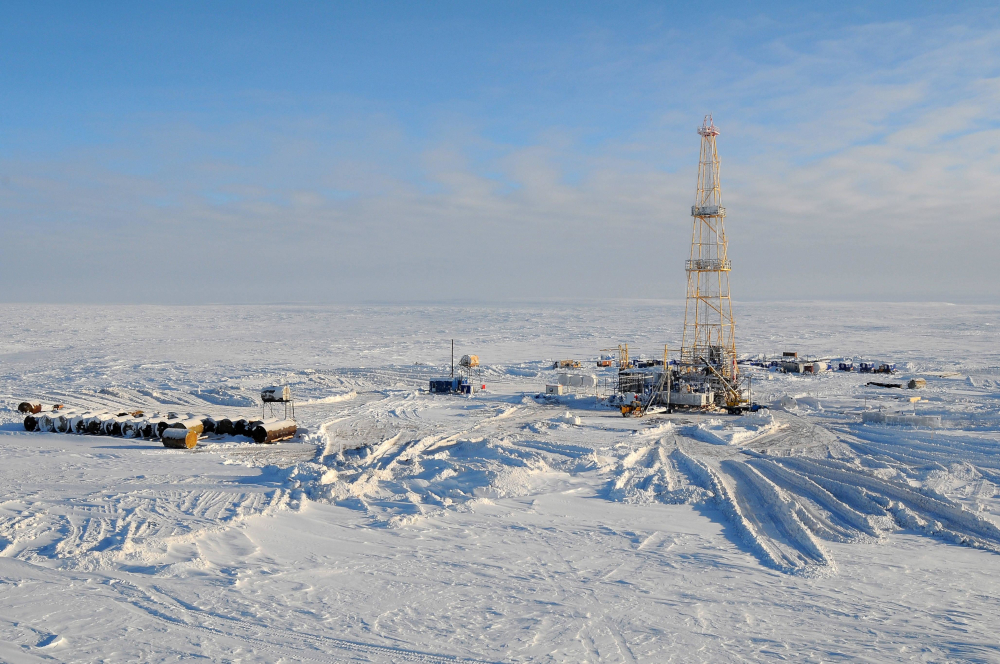

As for the development of Arctic land territories (referred to as the North), over the past decade, the Kremlin officials have adopted a series of strategic planning documents, the last of which is provided until 2025. On the one hand, the attention paid by the Russian government in this respect must result from the areas’ strong underinvestment, as exemplified by deficiencies in transport infrastructure, and risks related to the permafrost melting as both existing buildings and new strategic undertakings may eventually be threatened by construction risks. On the other hand, the Russians are aware of the Arctic’s huge potential as the region is rich in raw materials, accounting for most of Russia’s extraction of oil, gas, copper, cobalt, nickel, and platinum) while offering some military advantages (the shortest straight line distance to the U.S. territory).

Simultaneously, Moscow’s regional interests focus on the Arctic waters as they have become increasingly available to most kinds of human activity. In this context, the Russians hope to gain both economic and political benefits related to the ever-growing popularity of the northern transport route along the country’s coasts and the possibility to manage the continental shelf in an accurate manner. Thus, the aforementioned strategies seek to discuss both the extraction of raw materials from the Arctic Ocean seabed as well as the approach to potential fisheries. Such undertakings may hardly pass for a surprise as back in 2000, Russia was the first to launch legal efforts to recognize its rights to extend the state’s EEZ for further part of the shelf. The Russians hope to receive the ultimate decision within the next two years.

SOURCE: Denis Kozhevnikov © PAP/ITAR-TASS

SOURCE: Denis Kozhevnikov © PAP/ITAR-TASSNorthern Sea Route

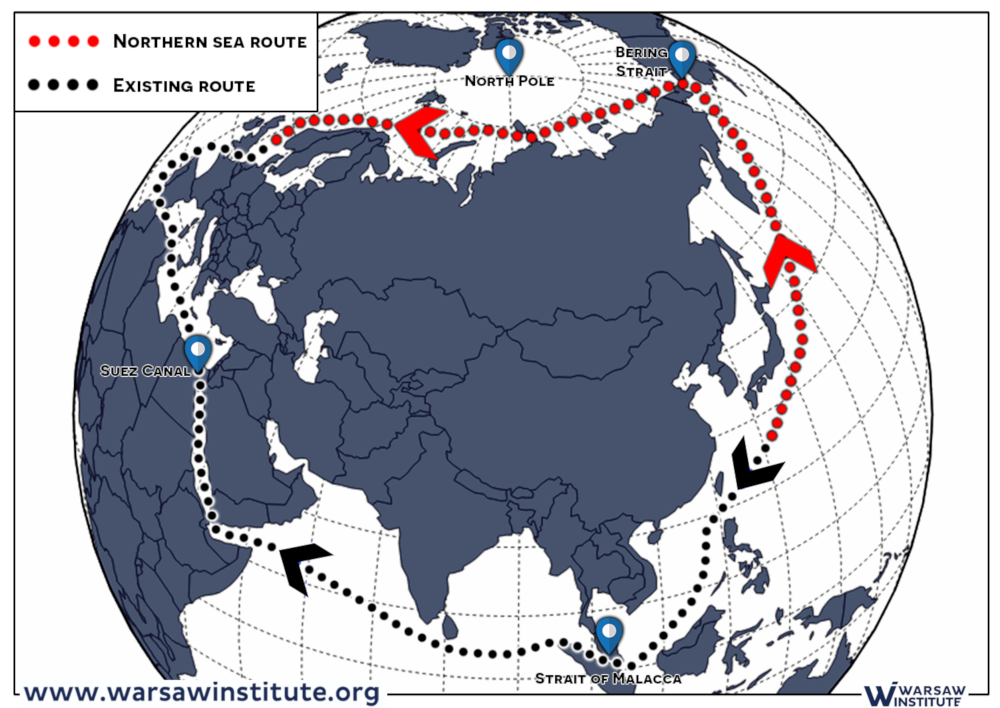

One of Russia’s three main objectives in the Arctic region provides for the development and promotion of the Northern Sea Route, referred to as the official name of a shipping lane running along the country’s northern coast. It would be a key maritime connection between Europe and Asia, making it possible to shorten the total travel time by one third. Yet Moscow’s plans are still the thing of the future as the Arctic ice cover forces the Russians to employ high-class naval units (that do not require any additional ice-breakers) in order to make the undertaking profitable. Even though, Russia hopes that the ever-growing climate changes, additionally fostered by progress in technology, will increase the cargo traffic through the Northern Sea from the current ratio of 17 million tonnes per year to 80 million tonnes in 2024.

The Kremlin’s optimistic forecasts, according to which by 2030 it may be even possible to reach the level of 41-72 million tonnes per year, are moderated by Western analysts, who seem yet to agree that a new maritime route might result in large opportunities. A similar idea was put forward by a non-Russian company as Denmark’s Maersk has already sent its container ship through the Northern Sea Route, though the firm emphasized that the full use of the new shipping lane is not yet feasible.

Russia has assumed that the ongoing development of the Northern Sea Route should be stimulated by various national investments, including extraction of raw materials (oil, gas, and coal), LNG production as well as the construction of port and handling infrastructure. Furthermore, the state’s decision-makers were in favor of purchasing a fleet of icebreakers that would enable domestic goods to be shipped both to Europe as well as to dynamic Asian markets, mostly to China. It is noteworthy that the Kremlin seeks to safeguard interests of Russian producers by introducing some controversial regulations, considered as incompatible with the freedom of navigation as guaranteed by international maritime law. In 2017, Russia adopted a law banning the transport of Russian energy resources through the Northern Sea Route by foreign-flag vessels. According to the recent amendments to the bill, all ships, including military ones, should also be built in Russian shipyards. Although the legislation provided for enabling non-Russian vessels to enter Russia’s zone, thus at least partly protecting interests of Russian gas producer Novatek, which still seems to arouse great controversies in the light of international law.

Arctic natural resources

Russian hopes linked to the Northern Sea Route development are directly related to the managing of the Arctic’s rich natural resources. When focusing on the most-referenced oil&gas sector (data for 2017), fields located north of the Arctic Circle account for 83 percent of Russian gas production (569 billion cubic meters per year) and 17.6 percent of the country’s total oil output 96 million tonnes per year). Except for the Prirazlomnoye field, currently explored by Gazprom Neft, these volumes are exploited from land deposits, from where resources, such as oil and natural gas, are either to a large extent or almost exclusively pumped via a pipeline network. According to the Russian forecasts, the current situation is bound to change due to the upcoming expansion on the Arctic shelf by the state-owned companies Gazprom and Rosneft, as both firms wield a monopoly to conduct such actions. In addition, it may be also about the consistent intensification of the LNG output capacity by Novatek while gas products would be then transported through maritime route.

Though Gazprom and Rosneft have announced to launch a large-scale production on the Arctic Ocean shelf (according to the latter, the shelf oil output may account for 20-30 percent on the state’s total production), both corporations have already started to feel effects of the 2014 sanctions that had prevented them from employing Western technologies. Therefore, the prospects for the Arctic’s LNG sector seem to be much more clear. The main driving force behind the undertaking is Russia’s private gas giant Novatek whose largest shareholders are closely linked to the Kremlin authorities. Thanks to such personal ties, the corporation was granted license areas on the Gydan and Yamal Peninsulas, tax reliefs as well as LNG export permission under the Yamal LNG project. Consequently, Novatek’s LNG output capacities in the Arctic region are estimated at 16.5 million tonnes per years while the company intends to double the production in the next decades. Yet the fleet of Arctic methane carriers is referred to as insufficient to handle Novatek’s supply for liquefied natural gas.

The militarization of the Arctic

Regardless of Russia’s economic interests in the Arctic area, including raw materials exploitation, fisheries and such initiatives as the Northern Sea Route, the Putin-led country seeks to intensify the militarization of the region that has been considered as a territory of “special military and strategic importance”[2]. For more than a decade, the Russians have been rebuilding a relatively dense network of military units behind the Arctic Circle while deploying significant air, sea and land forces to the area. According to the reports from Russia’s Defense Ministry (2017), only five years after signing the presidential decree on strengthening the Russian presence in the Arctic, it was planned to set up 425 military facilities of a total area of 700,000 square kilometers.

Not incidentally, the same period was marked by the establishment of the Northern Fleet Joint Strategic Command in 2014. Set up on the basis of the Russian Northern Fleet (including land and air forces), the unit was referred to a Russia’s fifth military district. Naturally, Russia’s undertakings, also military ones, may be perceived by the West as ostentatious and confrontational, which seems additionally fuelled by the provocative rhetorics of Russian decision-makers. Back in August 2018, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu warned against the growing risk of an armed conflict in the region.

SOURCE: KREMLIN.RU

SOURCE: KREMLIN.RURussia intensifies the militarization of the Arctic, as exemplified by handing over the first battalion of Arctic air defense systems Tor-M2DT to the Northern Fleet in November 2018, while the entire process seems to largely exceed the scope of foreign troop deployment to the region. Although some analysts warn against the imminent outbreak of a military conflict, it may be assumed that Russia does not so much intend to start an open confrontation; instead, the Putin-led country aims rather demonstrate its power which – if necessary – will make it possible to act using the fait accompli method. Practically speaking, Russia’s military potential may be measured for any instances of erosion of the international order when the Kremlin might unilaterally seek to reinforce its claims to the Lomonosov Bridge while expanding Moscow’s aspiration for total control over the Arctic region.

[1] In 2007, Russian explorers even planted their own flag on the seabed below the North Pole near the Lomonosov Ridge at the depth of 4 kilometers.

[2] Cf.: Основы государственной политики Российской Федерации в Арктике, July 14, 2001.

The publication of the Special Report was co-financed from the funds of the Civic Initiatives Fund Program 2018.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

_________________________________

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.