SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 22 October 2019

Russia in Africa: Weapons, Mercenaries, Spin Doctors.

The Kremlin eyes the African continent as yet another arena of a massive clash with the West, as it did under the Cold War reality. But their competition has now been of a rather practical and economic nature, pushing ideologies somewhere to the margin. Also, Moscow has enjoyed the positive image it had retained in Africa back from the Soviet times.

- Russia’s expansion across the Dark Continent will be best exemplified by the first-ever Russia-Africa summit, set to take place in the resort town of Sochi in October 2019. It comes as the culmination of years of Moscow’s heated political and economic efforts to nurture ties with its African peers, and intends to give the green light to open a new chapter.

- Russia’s clout on African soil runs on many tracks, and its expansion is geared primarily towards hybrid activities. In Moscow’s offer for Africa are mercenaries, military equipment, mining investments, nuclear power plants, and railway connections. Russian military specialists help those politicians that show a pro-Russian attitude.

- Their activities, or those of mercenaries, serve the Kremlin’s political goals to the very same extent, by offering tangible financial benefits to these business circles that hold close links to Vladimir Putin. Africa is viewed as a prospective source of wealth for Russian oligarchs –– a source of minerals and an outlet for Russian-made military weapons. These investments should pay off, both economically and –– more importantly –– politically.

- Besides establishing a large group of Russian friends in Africa, it is no less vital to deploy Moscow’s military forces to the continent, albeit carefully. Russia’s fielding of its mercenaries and combat advisors to the Dark Continent may give rise to building up its military presence. Moscow holds interest in creating military facilities in strategically important areas, also throughout the Horn of Africa.

- Inking fresh batches of military agreement deals in an effort to potentially boost Moscow’s capacity of establishing army facilities, or the issue related to economic affairs, runs the risk for Western countries, given Russia’s neutral stance on China. And the West is gradually losing both its impetus and interest in Africa. This paved the way for Russian expansion, enabling Moscow to fill the void left by the United States, as some time ago in Egypt.

July 26, 2018. South African soldiers greet Russian President Vladimir Putin, who arrived in South Africa to attend the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg. Source: KREMLIN.RU

July 26, 2018. South African soldiers greet Russian President Vladimir Putin, who arrived in South Africa to attend the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg. Source: KREMLIN.RU

“Russia regards Africa as an important and active participant in the emerging polycentric architecture of the world order and an ally in protecting international law against attempts to undermine it,” said Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov back in November 2018.[1] Shortly after, in December 2018, John Bolton, the then national security adviser, said in a speech at the Heritage Foundation that Russian and Chinese activities on African soil are detrimental to U.S. interests and those of the countries themselves (“threaten the financial independence of African nations; inhibit opportunities for US investment; interfere with U.S. military operations; and pose a significant threat to U.S. national security interests”). In 2015, Moscow staged a big comeback to the continent after a decades-long hiatus, setting its foot where the Soviet Union remained increasingly active in the Cold War era. This related both to the areas of security and economy, as exemplified by a massive surge in the value of Russian trade with African countries that rose from $3.4 billion in 2015 to $14.5 billion in 2016. Moscow’s growing involvement in African is, on the one hand, due to its urge for fresh alliance that emerged back in 2014 in the aftermath of a round of Western sanctions imposed on Russia over its annexation of Crimea from Ukraine. But there are other, far more critical reasons for Vladimir Putin’s country’s ever-increasing appetite for a pivot to the Dark Continent.

Africa has surged as an area with the ongoing efforts to revise the post Cold-War order being most evident –– it is witnessing both the entry of a superpower that had never before set its foot in the region (China) and the return of Russia, pushed out of Africa after 1991; a shift that takes place at the expense of both traditional postcolonial powers (France and the United Kingdom) and a top beneficiary of the Cold War (USA).[2] Given all this, Africa has become a giant battlefield in a fight between Russia in the West in what morphed into a new Cold War, a period of tensions with money having the advantage over ideological matters. With the development of global trade comes Africa’s availability to anyone who expresses interest in entering the local market, export raw materials, or trade their products to the continent’s growing population. In 30 years, Africa will be home to a quarter of the world’s total population. Given the dramatically poor economic situation in many African countries and relatively low financial costs needed to provide some political regimes with essential aid, it does not come as a surprise that Moscow keeps getting involved in backing more and more states across the Dark Continent. Besides, African leaders are aware that they may ask Russia for help as its authorities will not require them to respect democracy and human rights. Africa is an ever-growing potential customers market for military equipment and a continent that boasts vast mineral deposits. Not incidentally, Russian-African deals inked during the Kremlin visits of African leaders refer most often to selling military hardware and issuing licenses for the exploration of oil, gas, gold, and diamond deposits to Russian-based firms. Russia is in the hope of securing what China has already gotten; a Chinese analyst was quoted as saying that Beijing owes as many as 20 percent of its last-generation economic growth to the benefits that accrued from China’s African expansion.[3] 2013. President of Russia Vladimir Putin arrives in Durban, South Africa, on an official trip.

2013. President of Russia Vladimir Putin arrives in Durban, South Africa, on an official trip.Source: KREMLIN.RU

Russia is open for deepening ties with anyone who holds such an interest, with historical, ideology, or geopolitical matters being of little importance. The Kremlin’s push for new alliances allows it to simultaneously strengthen cooperation with two countries referred to as mutually hostile, like Algeria and Morocco. A comparable strategy is part of Russian policy within a single country too. In Libya, Moscow backs Haftar while nurturing friendly ties with the government Tripoli and, on the other hand, remaining committed, albeit unofficially, to offering help to a prominent son of the former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. Also, Russia has sent its mercenaries to the Central African Republic, who serve as a personal guard to the country’s president Faustin-Archange Touadéra while enjoying its role as a proxy to plot with Islamic rebel groups further in the country’s mainland. Moscow stands ready to launch talks and enter into cooperation with virtually anyone who meets a series of conditions, including allowing Moscow with full influence on regional policy so as to obstruct the importance of other powers. Russian military analysts say that Moscow should follow suit of France’s efforts in its former colonies, a model dubbed subsequently Françafrique (“French Africa”) that could provide the Kremlin with an opportunity to intervene on the side of its allies while combatting enemies and preventing their competitors from entering key countries.[4]

COLD WAR 2.0. ON AFRICAN SOIL

What stands out as a leading factor behind ongoing African-Russian partnership is their long-standing alliance dating back to the Soviet era. It is worthwhile to keep in mind that some representatives of African political elites graduated from Moscow-based universities. It is not without significance that Russia has no intention to chide authoritarian-style governments in Africa for their noncompliance with human rights, nor does it push for passing adequate reforms. Africa, for its part, is seeking for an alternative to China and the West. It sees Russia as a reliable partner, also due to the lack of Moscow’s efforts to colonize the continent, and the Soviet Union backed anti-colonial movements in many African countries. Furthermore, unlike its immediate predecessor, present-day Russia has no ambition to persuade its African peers to follow its political and economic patterns. Moscow has mobilized a batch of soft power tools, chiefly by promoting cooperation in the area of education: scholarships in Russia and further developing its network of Russian Centers of Science and Culture that already operate in Egypt, Morocco, Zambia, the Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Tunisia, and Ethiopia.[5]

Russia’s stepping into the Dark Continent is best exemplified by the Russia-Africa summit, scheduled to take place on October 23–24 in the Black Sea resort town of Sochi. Quite recently, State Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin said that the event “has no precedent in the history of Russian relations with African states, including the Soviet period when relations were very active.” The Sochi meeting will probably be geared towards a series of projects to be integrated jointly with the African Union and the Southern African Development Community. High on the agenda will be a plan to launch a free-trade zone on the grounds of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, or a document signed by 53 countries. The Kremlin aspires to ink a memorandum of understanding on cooperation between the African Union and the Eurasian Economic Community. No less attention will be given to what Moscow will arrange bilaterally with African participants of the Sochi meeting. Egypt took an active part in preparation for the upcoming Russia-Africa summit. Russian President Vladimir Putin and is Egyptian counterpart Abdel Fatteh al-Sisi discussed the issue on the sidelines of the G20 Osaka summit (June 29, 2019). Egypt will co-chair the Sochi meeting due to al-Sisi’s his year’s role as the Chairman of the African Union, a position that obliges him to represent the institution at international gatherings. Earlier in 2019, Moscow has hosted two large-scale worldwide forums devoted to cooperation with African countries in a bid to prepare the ground for the Russia-Africa meeting in Sochi. On June 20–22, 2019, Russia staged the Russia-Africa Economic Conference while some days later, between July 1 and 3, the State Duma, or the lower house of the Russian parliament, held the Russia-Africa inter-parliamentary meeting that attracted over 300 MPs from as many as 40 African countries.Russia’s expansion on African soil builds up its position in the United Nations, a quarter of whose members are African countries. Vladimir Putin’s goal is to amplify the Russian zone of influence in different world regions as part of his efforts to reconstruct Russia’s status of a mighty state standing in stark contrast to its Western peers. The Kremlin is therefore playing up Europe’s and Washington’s declining interest in the Dark Continent, exemplified by the latter’s steadily diminished military presence in various countries across Africa. In this respect, the People’s Republic of China may emerge ultimately as a leading adversary, though it had in the past filled the void left by the Soviet Union. In Africa, China holds a way more decisive advantage over Russia, which stems from the economic superiority of the Middle Kingdom. China’s activity differs from Russia’s by being less military and more economically oriented. But even here, Russia can boast some small achievements in its rivalry with China. In the Central African Republic, Moscow managed to impede Chinese efforts to buy stakes at French Areva’s Bakouma uranium mine, thus preventing Beijing from restoring full control of the site.[6]

November 19, 2018. Russian State Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin attends a meeting with African ambassadors, Source: KREMLIN.RU

November 19, 2018. Russian State Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin attends a meeting with African ambassadors, Source: KREMLIN.RURussia eyes Africa in terms of the field of confrontation with the West, especially if security issues are at stake. In Africa, Moscow finds it more convenient to sow chaos in a bid to harm the West, chiefly to such actions being both easier and cheaper than in Europe to be carried out. Russia’s resources are more modest that the Soviet Union’s, and the country itself is much weaker than the West compared to the time of the Cold War. This can involve sparking humanitarian catastrophes, which result in new refugee flows into Europe. The plan is to create new problems for Western governments, with Moscow thus eyeing a strong position of Libya, viewed as a key “transit country” for migrants heading to Europe.[7]

At the end of January 2019, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov traveled to the Maghreb, visiting Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. Among these three, Algeria is historically Russia’s closest partner in the region. In the wake of the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and Moscow’s hiatus on the continent, Algeria, a crucial ally in the Cold War era, was among Africa’s first countries to restore relations with Vladimir Putin’s state. In April 2001, Algiers also signed a Strategic Partnership with Moscow. Algeria remains a major purchaser of Russian weaponry and a vital partner in the energy sector, with Russia’s Transneft and Gazprom having indeed deepened their cooperation with Algeria’s Sonatrach.[8] Earlier this year, Russia announced it might start producing Lada automobiles in Algeria. What draws attention is Russian-Tunisian rapprochement after the Arab Spring unrest unfolded in some African countries. Between 2016 and 2017, these two struck a number of economic deals, among which a Strategic Partnership agreement. In early February 2019, the commander of U.S. Africa Command, Gen. Thomas Waldhauser, told the Senate Armed Services Committee that it is clear that Russia pushes its strategy along the northern part of Africa, southern bit of NATO, and the Mediterranean. In his remarks, he pointed to Russian inroads in the Central African Republic, paying attention to Russia’s outreach being part of an effort to gain access to raw materials on favorable conditions, which serves as the Central African Republic’s payoff for the Russian military presence in the area. But the same is true in various countries across the Dark Continent.[9]MILITARY COOPERATION

Recent years have seen an increase in the number of African countries that struck military cooperation deals with Russia. In 2018 itself, it inked such agreements with Guinea, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Madagascar, and the Central African Republic, while more may come at the Sochi gathering. For example, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari hopes to sign a military technical cooperation deal with Russia in a bid to purchase a bulk of Russian-made helicopters, aircraft, and tanks. “This is to help the Lagos government crush Boko Haram,” Nigerian ambassador to Russia said on October 11. Step by step, Russia is surging as an alternative to Western countries. In 2014, when the United Kingdom and the United States were in no rush to respond to Nigeria’s request for help, Nigeria turned to Russia for counter-terrorism training for its special forces and bought military hardware to fight Boko Haram.[10] So far Moscow has signed over 20 military cooperation deals with various countries across Africa: Tanzania, Eritrea, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Libya, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Mozambique, and Madagascar. Several hundred peace-keepers from African countries have been trained in Russia since 2006.

Among African states that are closely cooperating with Russian in the area of security is the Central African Republic. A special department tasked with representing the Russian army was established as part of the Central African Defense Ministry. Financed by the Russian state, the body consists of five people.[11] Under a deal signed during a Moscow visit of the President of the Republic of Congo Denis Sassou-Nguesso on May 23, 2019, Russia committed itself to send military specialists to the Republic of Congo who––as officially informed by the Russian side––will train Congolese soldiers and help to service Soviet-made munitions. Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin said that the contract in the first place concerned the maintenance and operation of Soviet-and Russian-made military hardware. The Congolese army has in its inventory artillery systems and helicopters. The recent agreement may serve as the first step to tighten arms cooperation between the two countries. It is unknown how many Russian troops will eventually be deployed to Congolese soil, nor is it sure that what has been officially stated will be the sole purpose of their stay in Africa, as exemplified by Russian military involvement in other African countries.[12]

A group of Russian military experts arrived at Nacala airport, Nampula Province, in early September 2019, local analysts said. The Russia-Mozambique security agreements pave the way for the Russian military to train and advise their Mozambican peers.[13] British newspaper The Times wrote a month later that “Russian mercenaries and military hardware have arrived in Mozambique to help the government fight jihadists.” These are Islamic fundamentalists who remain active in the country’s northern province of Cabo Delgado that holds gas fields, with Russia’s Rosneft having the ambition to unearth them. The group is reportedly composed of about 200 soldiers, including elite troops, three attack helicopters, and crew. The Kremlin has denied this.[14] Some sources say that Russia has sent 160 elite Russian military men to the country with the ultimate goal of launching in the country a mobile military intelligence base and a permanent naval military facility.[15] The latter variant appeared when Russian and Mozambican defense ministries inked a deal on tightening their bilateral cooperation on maritime activities in spring 2018, giving the green light for Russian-flagged naval vessels to dock at Mozambican ports.

A Russian special forces soldier. Source: Russian MoD

A Russian special forces soldier. Source: Russian MoDWith Moscow’s military partnership of various African nations often comes the matter of a potential Russian naval facility. Though in the Cold War era the Soviet Union had never had a permanent military base on the Dark Continent, it meddled militarily in some countries across Africa. Soviet warships used naval ports of Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Tunisia, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Guinea. At the time of the Angola civil war, Moscow offered support to the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in a move that paved the Soviet army’s way for accessing a Luanda military base for over a quarter of a century. Under some of the recent deals, Moscow is entitled to use local airfields or naval facilities. In 2016, Russian media outlets reported that Moscow was negotiating with Egypt’s al-Sisi regime on terms of access to the Sidi-Barrani base. The idea of opening a military base in Sudan was discussed during President Omar al-Bashir’s visit to Moscow in late 2017.

An alternative to Sudan, if Russia seeks to strengthen its ability to sustain naval deployments in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and western Indian Ocean, could be Eritrea. In September 2018, an Eritrean delegation led by ForeignMinister Osman Saleh met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in Sochi. At the meeting, the parties signed an agreement which may see the establishment of a logistics center in the Eritrean port of Assab[16]. Russia has also had contacts with the breakaway region of Somaliland. In exchange for creating an air and naval facility in the Djibouti-bordering town of Zeila, Russia would formally recognize the region’s independence from Somalia. [17] Once launched in Sudan and/or Eritrea, naval bases could build up Moscow’s intelligence services while interfering with the Red Sea shipping between the Mediterranean and the Arabian Sea. This raises a serious concern over U.S. shipping from and to the Persian Gulf.[18] Located only 300 kilometers from Jeddah, a Russian base would be considered by Saudi Arabia as a threat to its security as well as to the protection of oil and gas supplies from the Persian Gulf to Europe. Another country that would not be satisfied with such a state of matters is China as it has been building its zone of influence in Africa for a long time. The Russian base would also weaken the position of Ethiopia, considered as a military power in that part of Africa. According to Sudan, the Ethiopians may constitute a counterbalance to the Egyptian-Eritrean alliance.[19]

In some African nations, with particular regard to those being governed by authoritarian regimes, cooperation with Russia encompasses the spheres such as national security and special services. A group of at least 30 Russian military instructors arrived at Omar al-Bashir’s Sudan to train the Sudanese National Intelligence and Security Service, known as NISS, and other riot branches that quelled anti-government protests that swept across the country. In late August 2019, Russia and Mozambique struck an agreement on mutual protection of classified information, seen as a cover for actual cooperation between these two’s special forces. This is all the more striking as the deal was inked by Deputy Director of FSB Alexander Kupriazhkin and Mozambican Defense Minister Atanasio Mtumuke. At the same visit of the Mozambican delegation in August 2019, Russian and Mozambican interior ministries concluded a partnership agreement.[20] The Russian Security Council hosted delegations from Africa at the Ufa Security Conference on June 18–20, 2019, bringing together representatives of security structures from Egypt, Burundi, Namibia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tunisia, and Uganda.

TANKS, MERCENARIES, SPIN DOCTORS

The Russian Defense Ministry also invited many African leaders to its Army-2019 Forum, or Russia’s largest annual military exhibition, on June 25–30. At the Forum, Russia and Mali signed a military cooperation agreement. Sergei Shoigu also met with his Malian counterpart Gen. Ibrahim Dembele, pledging support for stabilization in Mali.

The Soviet Union was in the past a leading supplier of arms to African states. In the wake of a dramatic decline during the 1990s, the number of weapons exported increased again in the following decade. According to the Swedish think tank SIPRI, between 2012 and 2016 Russia had become the largest supplier of arms to Africa, accounting for 35 percent of arms exports to the region, way ahead of China (17 percent), the United States (9.6 percent), and France (6.9 percent). Exports of Russian-made weapons and military hardware to Africa amount currently to $4.6 billion annually, with a contract portfolio worth over $50 billion. The leading importers of Russian arms in Africa are Algeria (helicopters, tanks, submarines), Egypt (aircraft, air defence systems, helicopters), Angola (fighter jets, tanks, artillery systems, arms and ammunition), and Uganda (tanks, air defence systems), alongside Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sudan, and Rwanda.[21] In 2017, Russian arms trade with Africa doubled compared with 2012. In 2018, Russia concluded arms and military hardware trade deals with as many as 20 countries across Africa. The Russian arms trading monopoly Rosoboronexport accounts for a third of all weaponry supplies to the Dark Continent. In addition to arms exports and military trainings, the Russian Ministry of Defence is involved in the training of African military personnel, and also offers related opportunities at educational establishments in Russia. But what is of crucial importance is an off-the-record facet of Russia’s military and political partnership with African nations, especially those that remain profoundly destabilized, plunged into domestic conflicts, and waging wars with neighboring countries.

Russian-built helicopters are very popular in Africa. Source: Russian MoD

Russian-built helicopters are very popular in Africa. Source: Russian MoDHundreds of mercenaries linked to Russia have been fielded across Africa. Already a few years ago, the Russian RSB-Group company carried out an operation to demine an industrial facility in Libya on General Haftar’s request. Retired General Leonid Ivashov, president of the Academy of Geopolitical Problems, has confirmed thata private military company Patriot is present in Burundi.[22] Both Libya and Burundi have become a ground for Wagner Group mercenaries. They have been confirmed to operate in the Central African Republic and Sudan. They serve a dual role, as tools for securing Russian companies’ commercial interests while actually representing the Russian state in an effort to offer opportunities of playing a substantial role in domestic affairs of countries to where Russian mercenaries have been deployed. A leading figure is here Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian businessman close to the Russian president. His steps in Africa resemble those in Syria that was flooded by hundreds of Wagner contractors in exchange for hydrocarbon mining licenses.

In Sudan, mercenaries who served as a personal guard for the then leader Omar al-Bashir were chiefly tasked with protecting gold mines, with Prigozhin’s firm having access to raw material. The same occurred in the Central African Republic –– a country plunged in internal turmoil –– whose leader Faustin-Archange Touadera –– discouraged by his state’s bitter experience with France –– saw in Russia a new military protector. In 2017, the United States Security Council gave its nod to Russia’s training mission in the Central African Republic, altogether with an exemption to the UN arms embargo that allowed the African country to purchase some Russian-made weaponry. A group of some 250 Russian nationals, some of whom are servicemen and mercenaries, offer support for Touadera. Russian “hired guns” are guarding the president while a Russian citizen was appointed his national security advisor. In exchange for this, Lobaye Invest, a mining company connected to Prigozhin, secured diamond and gold mining licenses, far ahead of inking a formal military partnership deal with the Central African Republic in the summer of 2018. Both his companies, as well as first groups of mercenaries, arrived in the country in early 2018, and other contractors quickly followed suit. According to some regional media, as many as 1,400 Russians stationed in the CAR in April 2018. Prigozhin-affiliated entities focus primarily on safeguarding Russian business interests. Unofficial reports say they struck a deal with Islamic rebel fighters that remain active in the region with most of the Russian-controlled mines. In the summer of 2018, three independent Russian journalists fell victim to an ambush in the Central African Republic after they had arrived in the country to investigate local Wagner activities.[23] Three journalists were killed by unidentified assailants on the evening of July 31, 2018, while they were on their way to a town located in the area of deposits of gold, diamonds, and uranium, which is being currently under the protection of Prigozhin’s people. Both the United States and France, the latter being the CAR’s former colony master, expressed concern over Russian activities in this part of Africa. The head of U.S. Africa Command General Stephen Townsend described the mercenaries at Berengo, Wagner Group’s headquarters at Bokassa’s former palace, as “quasi-military” and closely linked to the Kremlin. The Central African Republic serves a leading role in the Russian strategy of advance in Africa. It has a border with Sudan –– a country that sees the ever-increasing Russian activity –– and way bigger countries that Moscow eyes as more valuable, of which the Democratic Republic of Congo.This is where Prigozhnin-affiliated people were fielded as hybrid warfare experts. They backed a candidacy of a politician that held close ties to the then leader of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their practical efforts rose Felix Tshisekedi to power in January 2019, paving Russia’s way for pursuing its interests on Congolese soil. Also, Russian specialists routinely look for offering information and policy-related support in countries across the Dark Continent. They use a social-media apparatus, also to promote Gaddafi’s son in Libya, and know-how to back government-owned media. Moscow is sending to Africa its spin doctors in a bid to keep African leaders in power, which is also Prigozhin’s activity, besides his private military company.

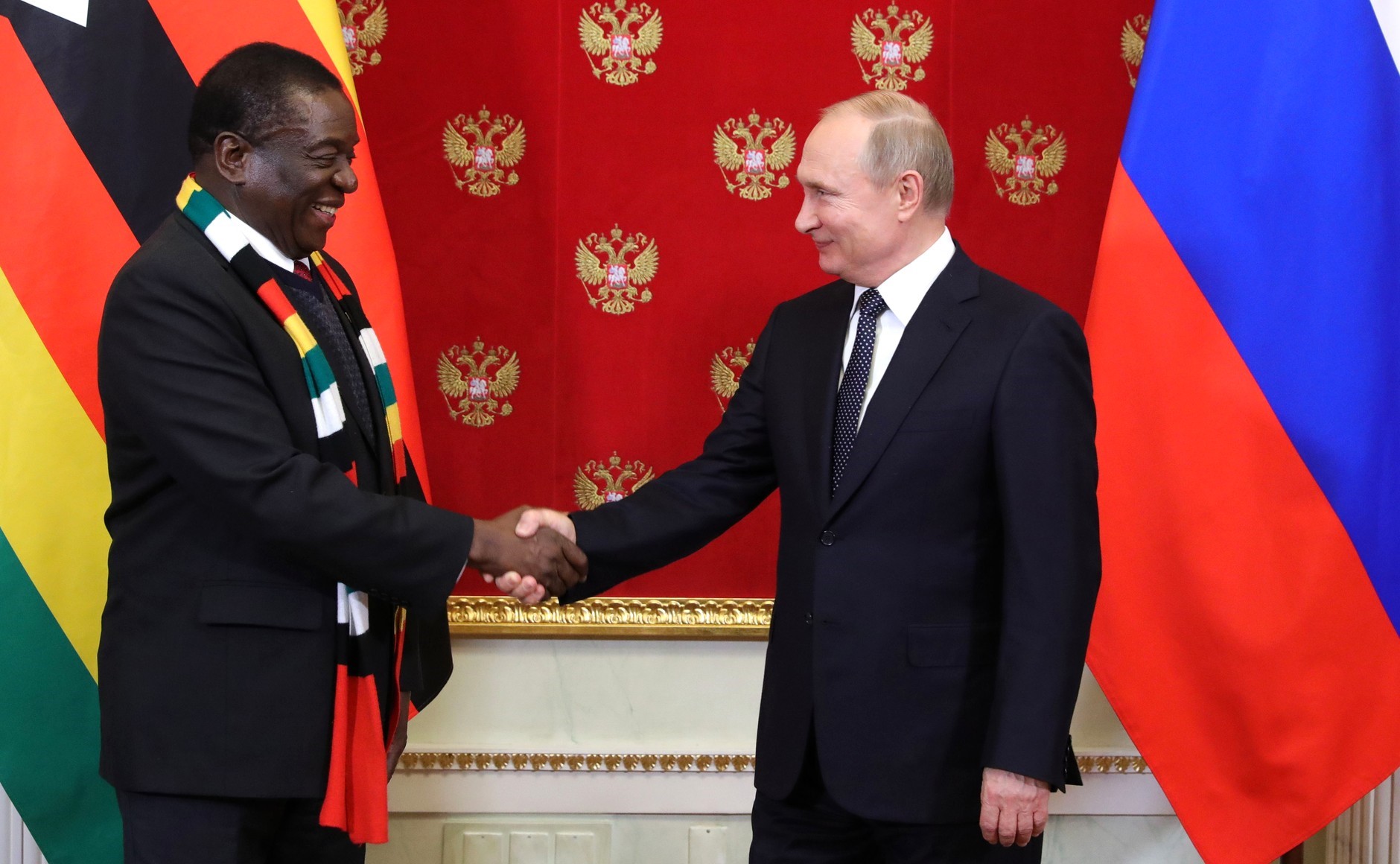

January, 2019. President of Zimbabwe visits the Kremlin. Source: KREMLIN.RU

January, 2019. President of Zimbabwe visits the Kremlin. Source: KREMLIN.RURussian independent information outlet Dozhd said on March 20, 2019, that a group of between 100 and 200 Russian political marketing experts might have been sent to take part in election campaigns throughout the Dark Continent. Some of them have allegedly been decorated with state awards for their efforts to nurture Russian interests in Africa, though their names were not found on any official ranking lists.[24] A U.S.-based Bloomberg agency reported that Russian political marketing pundits had been deployed to at least ten African countries across the continent: Sudan, the Central African Republic, Libya, Angola, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Madagascar, where Russian experts worked at the presidential campaign of 6 candidates out of all 35 politicians running for office. Bloomberg says that Prigozhin-linked entities provide their services in the areas such as protection, technology, and political support in exchange for being capable of extracting raw materials.[25] Russian experts so far have taken part in as many as 20 electoral campaigns across the continent, an example of which was Zimbabwe’s 2018 polling that yet again rose President Emmerson Mnangagwa to power. The country’s political opposition accused Russia of having meddled in the election. The state’s authorities have rejected these claims, though.[26]

OIL, GAS AND DIAMONDS

Naturally, Moscow’s aid for Mnangagwa was not unselfish. Zimbabwe is an instance of the Kremlin’s partnership with an African state, within the framework of which Russian-based firms advance the opportunity to bankroll local mineral deposits, albeit on preferential terms. In January 2019, Emmerson Mnangagwa made a trip to the Kremlin, seeking loans for his country’s crisis-ravaged economy. Still in the interview, Mnangagwa invited Russian companies to discuss potential investments in the country’s oil and gas projects as well as its energy sector. Among deals he signed with Russia was a fertilizer supply contract and two financing deals worth $267 million. There also came a recent decision of Alrosa, Russia ‘s leading diamond company, to come and mine in Zimbabwe while being granted the government’s full support. Following bilateral talks in the Kremlin, both countries sealed some deals, including the one on a joint platinum project. Zimbabwe’s incumbent government is currently considering repealing a law passed under Mugabe that prevented foreign investors from holding controlling stakes in local diamond mines. The government plans to target production of 12 million carats by 2023, up from 3.5 million carats in 2018.[27]

Alrosa’s advance in Zimbabwe shows Russian pivot to Africa in search of new and cheaper mineral fields. The same activity is seen to be performed by Rosneft, Lukoil and Zarubezhneft (oil, gas), Rusal (aluminum, bauxite) and Prigozhin-linked firms (gold). Though Russia boasts massive mineral fields, recent years have seen it suffering from the lack of some rare minerals, including chromium, manganese and titanium, while some reserves (nickel and tin) are on their way towards depletion. The list of Russian firms involved in Africa is long, with Rusal mining bauxite in Guinea, Rosneft operating gas and oilfields across Egypt, Mozambique and Algeria, as well as Lukoil that boasts own investments in Nigeria, Ghana and Cameroon.[28] In July 2018, Russia’s state exploration company Rosgeologia signed an agreement with Sudan to explore for gas in the Red Sea. In 2018, Gabon pushed forward an offer for additional mining licenses for Russian Zarubezhneft while a year before, Rosneft had concluded a deal with Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC).

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Russia actively extracts cobalt, gold and diamonds, as well as is unearthing uranium and diamonds in the Central African Republic. This is where Lobaye Invest, a mining company connected to Prigozhin, secured diamond and gold mining licenses in seven of the country’s fields. Of all African states, Sudan seems like a precious gem, classified as a leading producer of gold in Africa. Russian company M-Invest –– tied to Yevgeny Prigozhin –– was granted concessions for a gold mine in Sudan while its subsidiary Meroe Gold is currently operating on five mining sites across Sudan. Among other entities that are paving their way for unearthing Sudanese sold is Russian company Kush for Exploration & Production CO.Ltd, until 2016 under Gazprombank’s control, that got adequate licenses in November 2018.What is becoming more and more visible is Russia’s ongoing plan to develop the oil and gas industries. It is not about entering the countries that saw in the past Moscow’s decades-long presence, as in Libya. Moscow is setting its sights on expanding into Mozambique. In 2010, an Italian gas firm ENI discovered considerable gas fields there, a discovery that granted the country’s position among the world’s top gas-rich states. In August 2019, Russia forgave Mozambique nearly all of its debt to Moscow in exchange for favorable investment conditions. Rosneft signed a memorandum with Mozambique’s National Hydrocarbons Company (Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos E.P., ENH) to develop offshore natural gas fields in Mozambique.[29] During the visit of the Congolese president to Moscow in late May 2019, Lukoil signed a letter of intent with Congo’s state-run oil company SNPC. One of Russia’s biggest oil giants acquired a 25-percent stake in the hydrocarbon project in the Republic of Congo, operated by Italian oil and gas company Eni. This is Lukoil’s first energy project in the Republic of Congo yet another on African soil; the oil company so far has left its footprint in Cameroon, Nigeria, Ghana, and Egypt. The last of the four countries hosts onshore projects while the three remaining ones are where Russia develops its offshore ventures.[30]

May, 2019. Lukoil CEO Vagit Alekperov signs an investment agreement giving the company the green light to drill in the Congo shelf. Source: KREMLIN.RU

May, 2019. Lukoil CEO Vagit Alekperov signs an investment agreement giving the company the green light to drill in the Congo shelf. Source: KREMLIN.RUBack then, Russia and the Republic of Congo inked eight deals and other bilateral documents, some of which refer to cooperation in such sector as mass communication or nuclear energy. The nuclear industry is an example of Moscow’s ever-increasing push for new investments across Africa. In July 2018, Nigeria confirmed Rosatom’s plan to develop the country’s nuclear power plant.[31] Similar talks are underway with Angola. Moscow has signed memorandums of understanding on nuclear cooperation with Sudan, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of o Congo, Uganda, and Morocco. In August 2018, Rosatom’s proposal for building up its nuclear facilities premiered at a large-scale trade show in Zambia, a country that is home to the Center for Nuclear Science and Technology. Rosatom is also active in Ethiopia and Kenya.

Russia is flexing its economic muscles both in individual countries –– ith Egypt where Russia is pushing for a project of the Russian Industrial Zone worth a total of $200 million–– and across the African Union and various pan-African bodies. The Russian Export Center holds stakes at African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), a 50-member trade finance institution created in 1993 under the auspices of the African Development Bank. Teamed with Afreximbank, the Russian export institution bankrolls projects in Sierra Leone, Angola, Nigeria, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Moscow hopes to take advantage of its advancing cooperation with African peers to bolster bilateral trade and investments, as well as to compete with Western economic influence on African soil. But what Russia is doing in Africa cannot be compared to China’s investment offer for the Dark Continent. It can compete only in terms of mineral unearthing. While lacking the financial power of the Middle Kingdom, Russia has sought to use its military support, also mercenaries, to leverage its influence across Africa. And Africans are aware of this fact. Christian Malanga, an opposition politician in the Democratic Republic of Congo, put it bluntly, admitting that “China is the money and Russia is the muscle.”[32]

[1] http://duma.gov.ru/en/news/28831/

[2] http://www.ng.ru/dipkurer/2019-10-13/9_7700_africa.html?mc_cid=c0a26bafcc&mc_eid=337d3d692f

[3] http://www.ng.ru/dipkurer/2019-10-13/9_7700_africa.html?mc_cid=c0a26bafcc&mc_eid=337d3d692f

[4] https://topwar.ru/161723-francafrique-po-russki-ili-strategija-rossii-na-postsovetskom-prostranstve-.html?mc_cid=c0a26bafcc&mc_eid=337d3d692f

[5] http://www.er-duma.ru/news/olga-timofeeva-nasha-zadacha-dat-kachestvennyy-start-otnosheniyam-mezhdu-parlamentom-rf-i-parlamento/

[6] https://www.defence24.pl/rosja-zwieksza-zaangazowanie-w-afryce-analiza

[7] https://jamestown.org/program/kremlin-moves-in-africa-open-a-new-round-in-russias-broader-cold-war-against-the-west/

[8] https://jamestown.org/program/the-broader-regional-meaning-of-russian-foreign-minister-lavrovs-maghreb-tour/

[9] https://www.voanews.com/africa/us-general-warns-russian-chinese-inroads-africa

[10] https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI%20MEMO%206604

[11] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/rosja-wysyla-kolejnych-zolnierzy-afryki/

[12] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/rosja-wysyla-kolejnych-zolnierzy-afryki/

[13] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/rosyjscy-wojskowi-w-mozambiku-kolejny-afrykanski-kraj-blizej-moskwy/

[14] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/mozambique-calls-on-russian-firepower-t2205dxh9

[15] https://jamestown.org/program/russia-prepares-a-foothold-in-mozambique-risks-and-opportunities/

[16] https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-talks-eritrea-set-up-logistics-center-red-sea-coast-lavrov/29464939.html

[17] https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI%20MEMO%206604

[18] https://www.heritage.org/europe/commentary/russias-africa-ambitions

[19] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/rosyjska-baza-w-sudanie-nierealne/

[20] https://ria.ru/20190822/1557801839.html?mc_cid=c0a26bafcc&mc_eid=337d3d692f

[21] https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI%20MEMO%206604

[22] https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_russias_hired_guns_in_africa

[23] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/rosyjska-intryga-w-sercu-afryki/

[24] Media: w Afryce 100-200 rosyjskich ekspertów od marketingu politycznego, Polish Press Agency, March 20, 2019

[25] Ibidem

[26] https://www.svoboda.org/a/29610746.html

[27] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/zimbabwe-rosja-pomoc-za-diamenty/

[28] https://www.ft.com/content/a5648efa-1a4e-11e9-9e64-d150b3105d21

[29] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/prezydent-mozambiku-na-kremlu-korzysci-dla-rosnieftu/

[30] https://warsawinstitute.org/pl/prezydent-mozambiku-na-kremlu-korzysci-dla-rosnieftu/

[31] https://www.powermag.com/russia-will-help-nigeria-develop-nuclear-plant/

[32] https://www.ft.com/content/a5648efa-1a4e-11e9-9e64-d150b3105d21

The publication of the Special Report was co-financed from the funds of the Civic Initiatives Fund Program 2018.

The concept of analytical material was created thanks to co-financing from the Civil Society Organisations Development Programme 2019.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.