THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 4 November 2019 Author: Krzysztof Rak, PhD

Józef Piłsudski’s policy of maintaining the European status quo

Many prominent and influential historians claimed that Polish foreign policy in the interwar period was revisionist or had a destructive effect on the Versailles order. Its alleged culmination was the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of January 26, 1934. Based on this, a conclusion was drawn that Poland became co-responsible for the outbreak of World War II because it signed this pact with Germany.

Such views are present not only in today’s academic world but also in historical and political journalism. One of the first propagators of such claims was a British historian Hugh Seton-Watson, who claimed that one of the cornerstones of Polish foreign policy was “territorial greed”[1]. According to the researcher, the Non-Aggression Pact of January 26 was “the beginning of German-Polish active cooperation in implementing aggression in Eastern Europe.” Seton-Watson considers Poland of the 1930s as a “tool of German imperialism.” The Poles allegedly counted on the Germans to destroy the Soviets, and, in exchange for such cooperation, they were to receive a “large part of Russia” as a reward[2]. German historians Klaus Hildebrand and Andreas Hillgruber categorized Poland as a revisionist country, generally pointing to Warsaw’s policy towards Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, and Soviet Russia[3]. The French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle claimed, on the other hand, that Piłsudski and Beck “pursued an nineteenth-century brand of foreign policy full of secrecy and cynicism,” and that after 1933, they cheered Hitler on the destruction of the Versailles order.[4] Russian researchers Anatoly Torkunov and Mikhail Narinsky are of a similar opinion. In their textbook, the History of International Relations, they claimed that the Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact of January 26, 1934, strengthened Germany while undermining the Versailles order.[5]

It is essential to confront these views and compare them with the opinions and real politics of the principal architect of Polish foreign policy of that period – Józef Piłsudski.

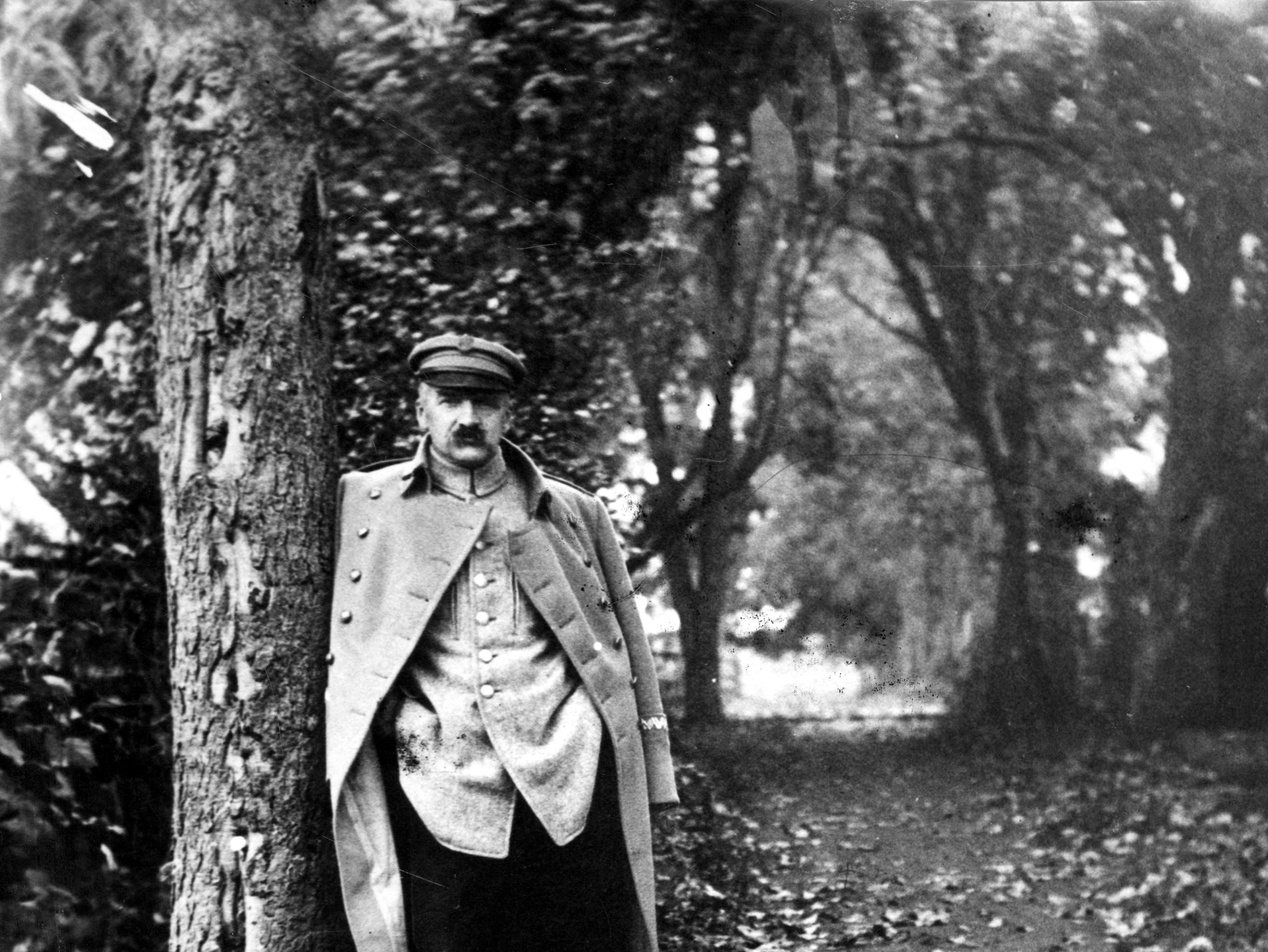

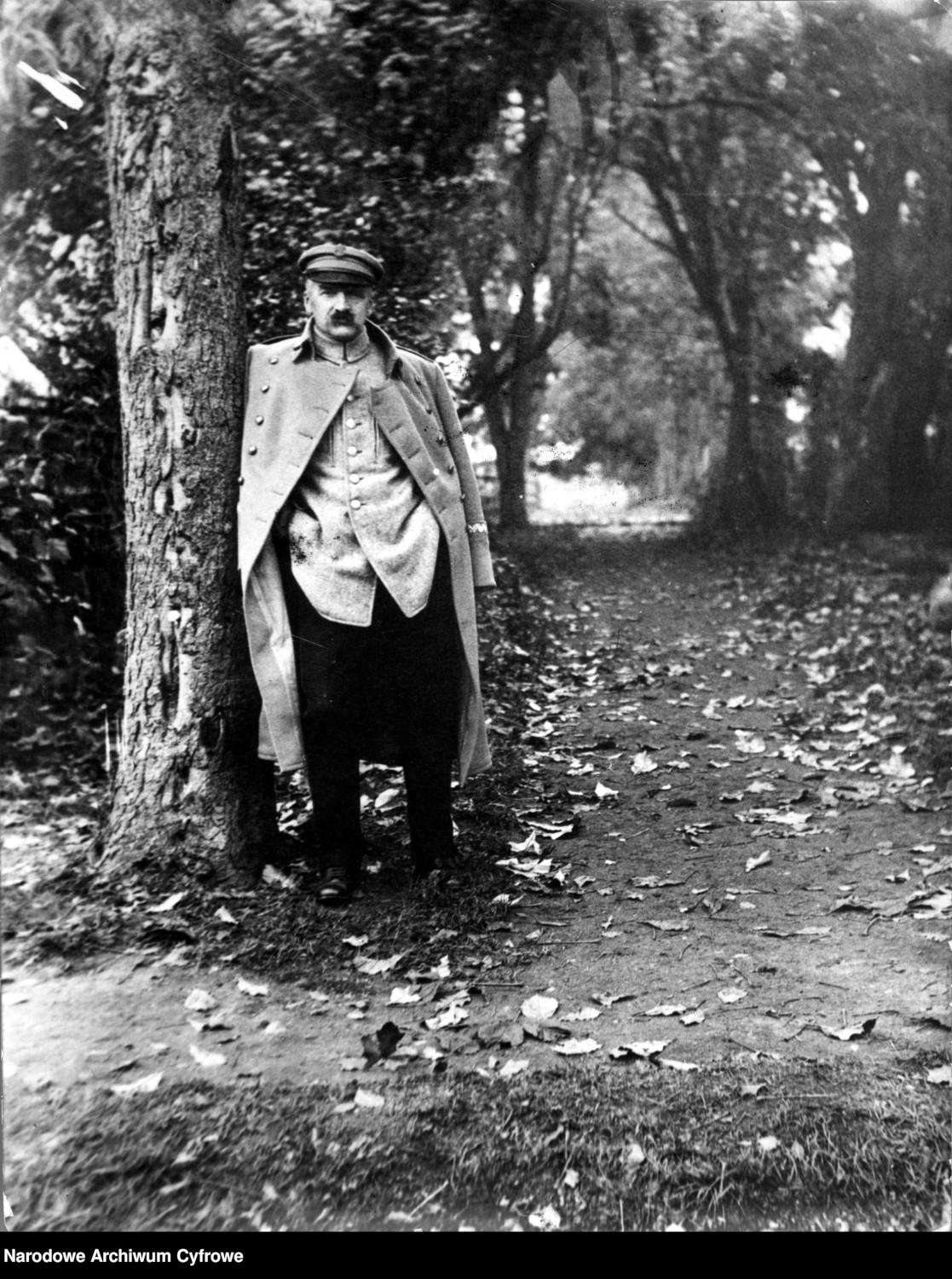

Józef Piłsudski, Marshall of Poland. Photograph taken between 1921 and 1926. Source: @NAC

Józef Piłsudski, Marshall of Poland. Photograph taken between 1921 and 1926. Source: @NACMaintaining the status quo

The most important program proposal defining the main principles of the foreign and security policy of the Second Republic of Poland was the memorial of the Chief of General Staff Władysław Sikorski, published in January 1922. The document was entitled “Foreign Policy from the Point of View of State Security” and was written by the head of national intelligence, Lt. Col. Ignacy Matuszewski, one of Piłsudski’s closest collaborators at that time – so it was most probably consistent with the Marshal’s views. According to Henryk Bułhak, the fundamental theses of this document constituted “a dogma of political thinking of the leading factors of the Second Republic of Poland throughout the entire period of its existence”[6]. The central “dogma” of this memorial proclaimed that Poland was interested “first of all in maintaining its status quo for as long as possible”[7]. This could not be achieved either through a simultaneous agreement with Poland’s neighbors (and above all with Germany and the USSR) or through an alliance with one of these neighbors against the other. The only way out was to establish an alliance with France and its allied countries.

Piłsudski perfectly understood the difficulty of Poland’s situation. He described it in an interview for “Kurier Poranny” on February 19, 1926. Discussing the issue of the organization of the Polish army, he pointed to the external conditions which Poland had to face:

“By a strange coincidence, despite the most obvious nonsense, Poland is continuously being accused in other countries of some war intentions and plans. Even in various disarmament projects, Poland is put in the foreground, although it is least armed and the newest, and therefore also has the feeblest military organization. I do not want to get into the motives and reasons for these accusations at the international level. I want to say that there is a clear and unambiguous desire in this to have a country in the middle of Europe, at the expense of which all European scores could be settled. […]

It is evident then that we are not the only ones who can believe that the existence and presence of Poland as we have today are not yet certain.[8]

Piłsudski had no illusions about assessing Poland’s potential. He certainly did not see his country as a superpower – unlike some of his successors. From this standpoint, he concluded that the existence and presence of Poland were not entirely certain. Piłsudski’s conviction that the state he was in charge of was weak did not change, even in the following years. He expressed it bluntly in 1930 in one of the interviews conducted by Władysław Baranowski: “…we are too weak to force something, to impose something on others, we are too week even in our affairs[9].

The basic idea of the Polish foreign policy of the interwar period was the conviction that Poland did not have a superpower status. It was a medium-sized country, but severe social and economic crises plagued it. As a result, it has not been able to change its international environment in line with its own interests. As a consequence, it had to focus on defending the status quo.

Locarno: world powers undermine the Versailles’ order

The first major challenge for Poland in maintaining the status quo was the Locarno treaties (December 1925). By signing them, Germany and the Western powers agreed to mutually recognize the inviolability of the western German border – translating de facto into the inviolability of the territorial order in Western Europe. This agreement did not concern the eastern borders of the Reich. In addition, from 1924, France began to express a wish to renegotiate the Polish-French military agreement of February 1921, which constituted the basis for the security of the Republic of Poland in the event of a threat both from Germany and the USSR. Policies of the powers in the mid-1920s constituted, therefore, an unambiguous prelude to territorial revision in Central and Eastern Europe.

In the notes made a year before his death, Minister Beck estimated that the Locarno treaties created “two categories – political and legal – of territorial importance in Europe,” and thus, “Germany was solemnly invited to invade the East.” Asked by him about his attitude towards Locarno, Piłsudski supposedly said: “every decent Pole spits when they hear these words.”

In April 1926, Germany and the USSR concluded the Berlin Treaty confirming the cooperation between Berlin and Moscow initiated in Rapallo (April 1922), which was clearly anti-Polish. Poland found itself in a challenging position between two revisionist powers growing in power, alongside the decreasing interest in maintaining the territorial order in Europe of the Western powers.[10]

Support Us

If content prepared by Warsaw Institute team is useful for you, please support our actions. Donations from private persons are necessary for the continuation of our mission.

After the coup d’état in May 1926, Piłsudski returned to power and nominated August Zalewski as Polish Foreign Minister. In November 1926, he took part in a meeting of the administration of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and, in a short speech, presented the main points of Polish foreign policy:

“There are two canons of Polish foreign policy, and they are inviolable. Firstly, Poland shall be utterly neutral towards Germany and Russia, so that both countries can be absolutely sure that it will never unite with one of them against the other. Secondly, it is necessary to maintain alliances with France and Romania as a guarantee of peace.[11]

It should be noted that these canons correspond precisely to the dogmas contained in Sikorski’s memorial of January 1922, which proves the continuity of the post-May Polish foreign policy.

Piłsudski presented his understanding of the international constellation in more detail during the first meeting of the State Defense Committee on November 26, 1926. The Committee operated under the leadership of the Polish President and was composed of the most important government representatives. During its meeting, Piłsudski gave a detailed account of the security and foreign policy of Poland. It is noteworthy to see how the Marshal described relations with Germany and the USSR. He was not afraid of the threat from the West, because he did not see “the possibility that Germans of this generation could attack us or anyone. The Germans are not able to make any military actions at the moment, and they are getting weaker every year because they are technically and morally demobilizing themselves.”[12] The Marshal had no doubt that the main threat to Poland’s security was the Soviet Union:

“There is a group of people in Russia who cannot live peacefully. These people, who form the upper strata of the state hierarchy, can move and lead Russia wherever they want. This element is a great danger – every surprise can happen – and it must be taken seriously.

“Anxious people in Russia will be looking for us because this country can take its revenge on us – although today’s authoritative considerations assure us that they do not want that revenge. However, internal party friction and a crisis of faith in Bolshevism can easily lead to a desire to get out of this situation by declaring war on us.”

At the moment, the Bolsheviks are working on the internal decomposition of our country, and this is their continuous work”.[13]

As it can be seen in what Piłsudski said, after the May coup, he did not see a direct war threat from both his great neighbors. The Germans were incapable of waging war, and the Soviets were only conducting internal diversions against Poland. This feeling of lack of direct threat was probably the reason why the Marshal tried to bring about a certain “equalization” (as it was commonly said at the time), of relations with Berlin and Moscow. This can be confirmed by his personal conversations with USSR envoy Pyotr Voykov (July 1926), German envoy Ulrich Rauscher (November 1926), and finally, German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann in Geneva (December 1927). These discussions, however, did not bring the expected results. The international environment was not conducive to these efforts: France after Locarno was looking for an agreement with Germany at the expense of Poland, Germany was becoming more and more hostile to revisionist attitudes. It did not seek to warm up relations with Poland, and the Soviet Union, cooperating with Germany and France, did not see any sense in striving for rapprochement with its western neighbor, which it treated as the main enemy. Polish foreign policy at the end of the 1920s did not try to implement any strategic initiatives. This was not only due to the internal political crisis related to the growing authoritarian tendencies in Piłsudski’s rule but also to economic problems caused, among other things, by the outbreak of the world crisis.

Piłsudski’s balancing policy

Piłsudski began to think about activating Polish foreign policy probably not until the end of 1930. This was caused by the gradual internal stabilization of his regime in Poland, as evidenced by the November elections to the Sejm and Senate concluded with the success of Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR). Under these circumstances, a “conference” took place on November 18, 1930, in which, among others, participated President Ignacy Mościcki, Marshal Piłsudski, and Józef Beck. During the meeting, the Marshal presented his political plan, initially noting that “we have five years of peaceful life and we need to be able to make use of this time”[14]. He then briefly diagnosed the previous governments of his own political camp. He considered that their disadvantage was the fact that “we did not move freely enough and were afraid to settle financial matters as well as foreign policy matters.” He also noted that when he is no longer there, “Poland will have to yield to foreigners in matters that do not require any concessions at all, because […] in many matters where there is pressure from foreigners, one can simply not yield”[15]. On this occasion, he criticized Zaleski, who had a habit of using threats that he will exacerbate the international situation in order to bargain more budget money for his department. The Marshal noted that Zaleski would then like to make concessions regarding national minorities, for which there was no consent, because “soon we could completely reverse our attitude and start to “suck up to the minorities.” In general, he negatively assessed the policy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accusing it of “going into a completely wrong direction, as it negates the east, tending to be a brown nose of the west”[16].

Sharp criticism of Polish foreign policy may come as a surprise as there was no doubt for the participants that foreign policy was exclusively the domain of the Marshal. Therefore, it had to refer to him mainly because, at that time, Piłsudski had to tolerate Zaleski’s at least. In other words, the Marshal had to accept that at the end of the 1920s, Polish foreign policy was submissive to the western powers (mainly France) and neglected (this is probably how the word “negligée” should be understood) what was happening on Poland’s eastern border. The Marshal’s tolerance for such a state of affairs was undoubtedly conscious and probably related to the internal situation in the country. Piłsudski set himself the overriding goal of stabilizing his power after the May coup. He probably had neither time nor resources to increase his activity on the international stage.

It was no accident that the activation of the Polish foreign policy coincided with the reorientation of the USSR’s policy towards Poland. In August 1931, Stalin ordered the Political Bureau and the People’s Commissioner for Foreign Affairs to finalize negotiations with Poland on the conclusion of a non-aggression pact.[17] This pact was on the agenda of bilateral relations as early as 1925, when on the eve of Locarno, the Head of the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, Georgy Chicherin, visited Warsaw. For six years, however, the parties could not agree on this issue, and it was only Stalin’s decision that caused the parties to initial the text of the pact in January 1932 and sign it in July. It was a turning point for Piłsudski’s foreign policy. Paradoxically, it was Stalin who invited Piłsudski to play and thus contributed to his debut on the international chessboard.

The rapprochement with the Soviet Union, which began at the beginning of 1932, allowed Piłsudski to start a tremendous diplomatic game. Piłsudski exchanged Zaleski for Beck at the end of 1932. Beck reported twice on the contents of the instruction he had received from the Marshal. In his speech to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials on November 3, 1937, on the occasion of the 5th anniversary of his assuming office, he recalled that on November 2, 1932, Piłsudski had given him two instructions:

“First,” the Marshal said to me: “You must remember that the times are coming when the conventional structure of international life, which had been dragging on for almost ten years, will be shaken. Forms, to which the world has almost become accustomed to, are crumbling. We will need to rethink our thoughts and rethink our verifications of states as if they were defining their right to speak in a broader or lesser sense. This phenomenon will be accompanied by many long complications, and for us, for Poland, it may result in taking up a fight against everyone, or at least improving our recent post-war history, which by its very nature left behind streaks of weakness, inaccuracies, and shortcomings. […]

The second thing –– in the same conversation, when he left, the Commander said: “But remember, above all, that you must not make considerations and plans beyond the strength of the instrument that is to perform them, because everything is done by people[18].”

Stalin’s decision allowed Piłsudski to start balancing between the continental powers. Until now, Poland has been condemned to relations with France, and the lack of maneuver made it its satellite. The finalization of the talks on the non-aggression pact with the USSR gave Poland the possibility of real balancing. This was necessary because, in the early 1930s, the situation for Poland became dramatic. France sought a strategic agreement with Germany at the expense of its ally and, at the same time, the satellite – Poland. On January 8 1933, a few days before Hitler took office as Chancellor, German Ambassador to Paris Roland Köhelm stated in a letter to Director Köpke that “every conversation with politicians (with sporadic exceptions) with whom he had met in the French capital since the beginning of his activity, very quickly and directly or indirectly touched upon the issue of the eastern German border”[19]. The French interlocutors of the ambassador blamed allies for the creation of the “corridor.” For that, they accused above all Lloyd George. In addition, more or less openly, they stated that “the division of Germany is illogical and poses a threat to peace in Europe”[20]. On February 22, 1933, the French Ambassador to Warsaw, Jules Laroche, in an interview with a German ambassador in Warsaw, von Moltke, once again raised the issue of the “corridor.” He expressed his satisfaction that, as a participant in the negotiations in Versailles, he had nothing to do with delimiting the Polish-German border, because already then he predicted that this would result in permanent hostility between the two countries. The French ambassador also said that: “In the old days, the disconnection of different areas of the state was not unusual, but such a state is actually incompatible with the modern concept of state territory. The corridor in the long term is unmaintainable, which is evident to anyone who has a map in their hands. A close-up with Germany would be in Poland’s interest, […], but it is impossible without the liquidation of the corridor. “[21]

In 1932-1933 France strived for reaching an agreement with Germany, for which it wanted to pay by revising the Polish-German border. However, the weakness of the German armed forces prevented Paris from implementing these plans.

The development of Polish-Soviet cooperation was supposed to be an argument for Germany for the normalization of relations with Poland, while for France, an obstacle to the transformation of the European status quo. Hitler’s rise to power at the beginning of 1933 proved to be an extremely favorable circumstance for Piłsudski’s policy. Hitler had been looking for contact with Piłsudski since at least the end of 1930. Through his unofficial emissaries, he tried to signal to him the possibility of a strategic agreement. He wanted to enter into a military alliance with Poland in order to conquer the USSR, the effect of which was to gain new living space for the German nation.[22] Although Piłsudski did not respond positively to these attempts, he had remembered them and made use of them in his political game in 1933. In March 1933, Piłsudski decided to also sound Stalin and Hitler out in terms of rapprochement. He did not have to wait long for the effects of his game. On May 2, 1933, Hitler received Alfred Wysocki, Ambassador of Poland to Germany, and declared that in his relations with Poland, he would conduct a policy fully compliant with the existing treaties[23]. Piłsudski was simultaneously sounding out Joseph Stalin. At the beginning of May, he sent to Moscow as his emissary Bogusław Miedziński, editor-in-chief of “Gazeta Polska,” who had previously held, among others, the positions of head of Polish intelligence and minister in the Polish government. Miedziński, through Karl Radek, head of the International Information Bureau at the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) and editor of Izvestia, a daily newspaper in Russia, offered Stalin, on behalf of Piłsudski, “a proposal for serious cooperation in the field of international politics”[24]. Karol Radek revisited Warsaw on behalf of Stalin in July 1933 and presented to the Polish side a proposal for an anti-German military alliance. Piłsudski, contrary to the expectations of his co-workers, did not give a negative answer. He ordered to inform the Stalin’s emissary that the Soviet suggestions would be taken into consideration by the Polish side, but at the moment, they are premature.[25] At the same time, Piłsudski continued his diplomatic offensive in Germany. At the end of September 1933, Minister Beck made it clear to the Foreign Minister of the Reich Konstatin von Neurath that the Polish government wanted to “gradually regulate most of the open issues through direct talks”[26]. When Germany withdrew from the League of Nations in October 1933, Piłsudski ordered the new Polish Ambassador in Berlin, Józef Lipski, to meet with Hitler and demand compensation. Hitler received Lipski on November 15, 1933, and declared his willingness to “exclude war from Polish-German relations” in the form of a treaty[27]. Following this discussion, both sides issued a communiqué stating that they ‘renounce the use of force’ in their bilateral relations[28]. In December 1933, Hermann Rauschning came to Warsaw with a message from Hitler[29]. During the almost one and a half-hour-long conversation, Piłsudski, declaring his willingness to have closer ties with the Germans, stipulated that he would not agree to participate in a possible military expedition to the USSR.[30] In December, the Polish-German talks on the joint declaration of non-aggression entered a decisive phase, and on January 26, 1934, it was signed by the MP Lipski and Minister Neurath. Warsaw informed Moscow about this phase of negotiations, but it did not inform Paris. Nevertheless, Stalin began to slow down the Polish-Soviet rapprochement from spring 1934, although the Soviets were aware that the declaration was not directed against the USSR.[31] At the beginning of 1935, Hitler, through his envoy Hermann Göring, urged Polish politicians and military to join a joint crusade against the USSR. Piłsudski definitely rejected the possibility of Poland’s participation in this project.[32] In July 1935, less than two months after Piłsudski’s death, Minister Beck confirmed this position in a conversation with Hitler in Berlin.[33]

In the years 1932-1933, Poland strengthened its international position, balancing in the triangle Paris-Berlin-Moscow. It is worth noting that its position has not improved as a result of the increase in its superpower potential (increase in population, economy, and army), but as a result of a successful diplomatic maneuver. Poland, as a result of the change of policy by Stalin and then Hitler[34], and as a result of Piłsudski’s use of this situation, broke out of its existing dependence on Paris.

NEWSLETTER

However, this balancing policy was entirely defensive, as it was a response to the Franco-German agreements of 1932-1933 aimed at territorial revision at the expense of Poland. Thus, the Polish-German declaration of non-aggression was for Poland a successful attempt to maintain the Versailles order in Central Europe. It was only in 1938 that Germany and the Western powers succeeded in destroying it when they decided to partition Czechoslovakia.

Chancellor of the Third Reich Adolf Hitler accompanied by officials at a parade. On the side, divisions of the army are visible, and in the distance, the Berlin Victory Column, 1939. Source: @NAC

Chancellor of the Third Reich Adolf Hitler accompanied by officials at a parade. On the side, divisions of the army are visible, and in the distance, the Berlin Victory Column, 1939. Source: @NACThe Marshal takes stock of his foreign policy

With regard to Piłsudski’s undoubted diplomatic success in 1932-1934, it is impossible not to ask a few questions. How did he intend to continue the rapprochement with Stalin and the agreement with Hitler? Did he consider Polish independence to be permanent? How did he see the future of European politics?

Piłsudski was aware that his life was coming to an end. He often mentioned this during meetings with his closest colleagues. He was also getting physically weaker and weaker, which was also noticed by foreign guests, whom he received in the last years of his life. That is why he was interested not only in the future but also in the past, in summarizing his achievements on the international stage. A good example was the Belvedere Conference on March 7, 1934, attended by President Mościcki, Marshal Piłsudski, former Prime Ministers Bartel, Prystor, Jędrzejewicz, Sławek, Świtalski, and Minister Beck. The Marshal explained at the very beginning that he was inspired by the example of England, where “in moments of a nuisance to the state,” the king convenes a meeting with the participation of former prime ministers. He admitted that he held off on convening the conference because “he did not want to hold it at a time when certain foreign affairs were not yet mature, they were in the middle of settling with the entire danger of risk.” He then continued with historical deliberations. He recalled the times of Catherine the Great and Frederick the Great when Russia and Prussia made a deal, and Poland was “torn to pieces.” He noticed that this “danger always exists for Poland.” After World War I, however, it was smaller, because both powers were weaker due to the fact that “Germany was conquered by Entente and Russia was conquered by Piłsudski.” However, in 1922, Berlin and Moscow made a deal in Rapallo that was not only against Poland but “rather against the whole world.” The position of Poland at that time was challenging:

“Poland was the focus of trouble and eternal fear that it was the source of disagreement. The alliance with France did not give it enough strength. Poland had to sacrifice a lot. This threat to Poland was exploited by everyone… On the Polish side, there was only one way to do this: to suck up to everyone… and to be shat on while doing that.”[35]

This unfavorable situation changed when Moscow entered the policy of rapprochement with Poland. However, on the German side, the Marshal came across a “hostile attitude, which, in detailed and minor matters, was even harassing.” However, he was able to take advantage of the moment when Germany withdrew from the League of Nations and made Hitler choose – either he would guarantee the security of Poland, or “[…] the Commander would have to use in his military work a defensive system clearly turned against the Germans”. Hitler unexpectedly eagerly picked up on this idea, and as a result, The German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact was signed. Piłsudski explained this in the following way:

“In this context, Hitler acted bravely against the Prussians when beginning to declare the recognition of Poland as a state officially. The Commander gives less importance to the signed documents than to the fact that the psychology of the German nation about Poland changes because of Hitler’s position. Therefore, even if the Prussians came to power, which would be the worst for us, this psychological change in the German nation would be an obstacle to their conversion to the old anti-Polish policy. The Commander then expressed his appreciation for the Germans that they know how to proceed reasonably, step by step.[36]

Piłsudski believed that the agreement with Moscow and Berlin caused “huge transformations” on the international arena, and he “won a situation for Poland which [it] never had.” The Marshal boasted that he had succeeded in doing so without making additional commitments to Berlin and Moscow, which was particularly difficult given the current hostility between these two. Moreover, Poland did not have to commit to supporting one side against the other. He recommended maintaining the previous alliances and noted that it would now be easier, because, having signed both non-aggression agreements, Poland would not have to pay for their preservation. This remark, of course, referred to France, which was not literally mentioned by the Marshal. Piłsudski was no longer so optimistic about the future:

“However, the Commander does not believe and warns not to believe that the settlement of peaceful relations between Poland and both neighbors would last forever, and the Commander calculates that good relations between Poland and Germany may still last four more years because of the mental changes taking place in the German nation, but whether they last for more – the Commander does not guarantee.

If the Commander is not there, it will be challenging to maintain this arrangement of things, because the Commander has the gift of inventiveness to postpone things or put them differently, if necessary. “That is the clever mind he has got,” said the Commander jokingly.”[37]

In the end, Piłsudski said that in recent years, he had worked hard to guarantee the security of Poland through diplomatic channels. He respected three fundamental principles that could be called his diplomatic will:

“1. Keeping to the rule that all comes out only in “Selbstbeschränkung.” You have to limit your goals, and [that] the worst is the ambaschränktesten ist bałwanisches Denken [the publishers of the Świtalski diary translated it as “the obtuse way of thinking is the most limited one”].

2) Never lower your head, that is to say, that it is necessary to respect your dignity, which has always produced excellent results for the Commander.

3) Poland’s mission is in the East, that is here Poland can reach for the opportunity to become an influential factor in the East. Do not interfere or try to influence relations between western countries. In order to achieve this influence in the East, it is worth it to sacrifice much in terms of Poland’s relations with Western countries.[38]

At the end of the conference, the Marshal noted that the stabilization of Poland’s internal situation is due to the fact that external, foreign forces cannot, through their influence on the internal factors of Poland, influence the direction of Poland’s foreign policy.

In his diplomatic will, Piłsudski did not give a detailed strategy to his successors. Except for the remark that “Poland’s mission is in the East,” which meant that the Eastern direction of Polish foreign policy was more important to him than the Western one. He probably wanted to say that the real potential of Poland does not allow it to shape the balance of power in Western Europe but is sufficient to influence the order in Central and Eastern Europe[39]. The Marshal focused on emphasizing his political methodology. This is because he pointed to the “gift of the inventiveness of postponing things or putting them differently” and “self-limitation.” This is not the case here, because he understood that sophisticated strategies, doctrines, or programs could not be effectively implemented in foreign policy. This is because international reality is exceptionally complicated and is full of uncertainties. If Piłsudski had a long-term strategy and believed in its effectiveness, he would have passed it on to his successors. His message, however, was of a different type – it pointed to the ability to stall and to act unconventionally and surprisingly. Piłsudski’s “cleverness” lies in the ability to see and take advantage of an opportunity, and thus a kind of political opportunism, which in its source, undervalued meaning, translates into the ability to take advantage of favorable sets of events. It is, therefore, a kind of political realism or a political attitude characterized by respect for reality and the awareness that a politician should, above all, respect it, and not try to change it, because it simply cannot be done. In short, an effective policy must be characterized by humility in the face of reality.

Józef Piłsudski, Marshall of Poland – a profile portrait photograph, 1933. Source: @NAC

Józef Piłsudski, Marshall of Poland – a profile portrait photograph, 1933. Source: @NACConclusions

How to treat accusations of destroying the Versailles order in this context? My shortest answer is this: it is the result of a narrowing of the research perspective of the researchers formulating this type of accusations. These scholars simply did not see or ignored certain facts and conditions.

First of all, that Piłsudski was aware of the weakness of Poland. He indeed did not perceive it as a superpower, as some of his successors did, and therefore was realistic about the fact that Poland was not able to change the international order.

Secondly, Piłsudski’s German policy was closely related to his Soviet policy, and his aim was to balance between Moscow and Berlin. Most researchers are not aware of how far the Polish-Soviet rapprochement went in 1933 (in July in Warsaw, Beck spoke with Stalin’s envoy Karol Radek about the cooperation of Poland and the USSR in defending the “corridor”)[40].

Thirdly, Poland was perceived as an aggressive state that could resort to war in its foreign policy, the most famous example of which was the alleged threat of a “preventive war” against Germany in 1933. From today’s perspective, everything indicates that it was a bluff from Piłsudski because there is no evidence that Poland wanted to attack Germany at that time. Despite this, German historians are still promoting the thesis of preventive war.

Fourthly, it should also be pointed out that the military Polish-French alliance – of fundamental importance for Poland’s security – has been weakening since 1924. First, the French questioned the guarantees in the event of a conflict with the USSR, and then also in the event of a conflict with Germany. In the early 1930s, they made the subject of the Polish-German border part of the agenda for German-French relations. In the first months of 1933, it was French diplomats who persuaded Berlin to take action against Poland.

To sum up, probably, the aim of the thesis about revisionism of Polish foreign policy is to hide the fact that constituted a fundamental element of the policy of the most important powers of those times, and that Central Europe was to become its victim. For those who claim that Poland was co-responsible for the outbreak of World War II, let us once again recall the actual history. In 1933 Hitler began to make strenuous preparations for the war against the USSR. His goal was to create a coalition in which Poland, among others, would play a major role. The latter, not agreeing to participate in the anti-Soviet alliance, thwarted Hitler’s intentions. It sought instead to maintain the status quo on the continent and, therefore, consistently refused to ally with Germany or the Soviets. The leader of the Third Reich had to change his plans, decided to attack Poland, and formed a short-lived alliance with his main enemy, the Soviet Union. The main reason for the outbreak of World War II was, therefore, Germany’s desire to rule over Central and Eastern Europe. However, there would be no success for Hitler in the 1930s without the consistent policy of concessions from France and Britain. It is remarkably ironic that 80 years after the outbreak of war, it is still necessary to prove that the superpowers, above all Germany, and then the Soviet Union, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom, are to blame for it.

[1] H. Seton-Watson, Eastern Europe between the Wars, Cambridge 1946, p. 189.

[2] Ibid., p. 388.

[3] See K. Hildebrand, Das vergangene Reich. Deutsche Auβenpolitik von Bismarck bis Hitler, Stuttgart 1996, pp. 586-587 and A. Hillgruber, Niemcy i Polska w polityce międzynarodowej 1933-1939, in Czubiński Antoni, Kulak Zbigniew [ed.], Stosunki polsko-niemieckie 1933-1945. XVIII Konferencja Wspólnej Komisji Podręcznikowej PRL-RFN Historyków, 28.05-02.06.1985, Nowogard. Poznań 1988, pp. 61-62)

[4] See J.B. Duroselle, La décadence 1932-1939. Politique étrangère de la France, Paris 1985; I am using an English translation: J.B. Duroselle, France, and the Nazi Threat. The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932-1939, New York 2004, pp. 65-66.

[5] See. А. Торкунов, М. Наринский [eds.], История международных отношений. В 3 томах., vol. II, Межвоенный период и Вторая мировая война, Москва 2012, p. 125.

[6] Henryk Bułhak, Polska-Francja z dziejów sojuszu 1922-1939. Cz. I (1922-1932), Warszawa 1993, p. 19.

[7] Dokumenty z dziejów polskiej polityki zagranicznej 1918-1939, vol. I 1918-1932, Jędruszczak Tadeusz, Nowak-Kiełbikowa Maria (ed.), Warsaw 1989, p. 183.

[8] J. Piłsudski, Pisma zbiorowe, vol. 8, Warsaw 1991, pp. 290, 292-294.

[9] W. Baranowski, Rozmowy z Piłsudskim 1916-1931, Warsaw 1938, p. 223.

[10] See T. Komarnicki, Józef Piłsudski i polska racja stanu, London, 1967, p. 19.

[11] A. Zaleski, Wspomnienia, Warsaw, 2017, p. 201.

[12] Ibid., p. 82.

[13] Ibid., p. 83.

[14] K. Świtalski, wyd. cyt., Warsaw, 1992, p. 524.

[15] Ibid., pp. 524-525.

[16] Ibid., p. 525.

[17] See. Сталин и Каганович. Переписка. 1931—1936 гг., Хлевнюк О.В., Дэвис Р.У., Кошелева Л.П., Рис Э.А., Роговая Л.А. (сост.), Moscow 2001, doc. no. 35, p. 71.

[18] Józef Beck, Przemówienia, deklaracje, wywiady 1931-1937, Warsaw 1938, p. 327.

[19] ADAP, doc. No. 265, p. 565.

[20] Ibid.

[21] ADAP, C, I/1, doc. No. 34, p. 72.

[22] The thesis widespread in historiography, according to which Hitler formulated his policy of rapprochement only at the turn of April and May 1933 under the influence of, among others, the threat of preventive war on the part of Poland and isolation on the international arena, is undefendable in the light of my earlier research in the book Polska – niespełniony sojusznik Hitlera. See. K. Rak, Polska – niespełniony sojusznik Hitlera, [Poland –- Hitler’s unfulfilled ally], Warsaw 2019.

[23] See PDD, 1933, doc. 127, pp. 282-283.

[24] Letter from Jan Berson to Bogusław Miedziński, Moscow, June 1, 1933. (AAN, MSZ, p. 6748A).

[25] See Bogusław Miedziński, Pakty wilanowskie, Kultura 1963, no. 7-8, pp. 113-133.

[26] ADAP, C, I/2, doc. 449, p. 828.

[27] PDD, 1933, doc. No, 320, p. 714.

[28]. See PDD, 1933, doc. No. 328, pp. 732-734, and ADAP, C, I/1, p. 126, footnote 2.

[29] ADAP, C, Bd. II/1, doc. No. 11, pp. 13-14.

[30] I present the course of Piłsudski’s conversation with Rauschning on the basis of a note prepared based on an oral account of Rauschning, written by Gerhard Köpke, Head of Division II of the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on December 14, 1933, in Berlin. See PAAA, Geheimakten 1920-1936, R 31076-1 or also PAAA, Büro Reichsminister, Akten betreffend: Polen, Bd. 10, R 28323k.

[31] See Документы внешней политики СССР. Том 17. 1 января — 31 декабря 1934 г, Moscow 1971, doc. no. 53, p. 139.

[32] See PDD, 1935, doc. no. 48, p. 113.

[33] See ibid., doc. no. 218, pp. 499-502.

[34] While reporting on the course of the conference at the Chief of State’s Office on January 31, 1934, Świtalski noted the following remark by Piłsudski: “If it weren’t for Hitler, many things wouldn’t have worked out.” (K. Świtalski, ed. cit., p. 654).

[35] K. Świtalski, ed. cit., p. 659.

[36] Ibid., p. 660.

[37] Ibid., pp. 660-661.

[38] Ibid., p. 661.

[39]. A similar idea was expressed by Piłsudski on April 29, 1931, during a meeting in the Belvedere, attended by President Mościcki, Sławek, Prystor, Świtalski, and Beck: “The Commander constantly believes that our focus in the context of foreign policy is in the East – we can be strong there and the Commander always considers it senseless for Poland to get into Western foreign relations too eagerly, because there is nothing else for us other than nose-browning the West. (K. Świtalski, ed. cit., p. 608).

[40] See B. Musiał, J. Szumski (ed.), Genesis of the Hitler-Stalin Pact. Facts and propaganda, Warsaw, 2012, p. 118.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.