THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 24 September 2018 Author: Joanna Antczak, PhD

Expenditure on cybersecurity of the Visegrad Group countries

Nowadays, cyber threats have become increasingly strategic in nature, covering all activities of the state, including its security and defense system.

Cybercrime is causing greater losses to national economies, businesses as well as private individuals than ever before, with cyber methods now being used to influence democratic elections in individual countries. On the one hand, armed forces are there to protect citizens from such attacks, while on the other the very same forces develop their proper offensive capabilities. Therefore, cyber methods are seen as an effective deterrent when making political or military decisions; also, they can be used as a means of a retaliation or response to political or military actions of other countries (such as the recent changes made by the US President Donald Trump, that give even more freedom when it comes to offensive actions).

Cybersecurity is a matter which cannot be considered in isolation. In order to ensure the digital security within a given state, its institutions and citizens, a number of entities have to engage in dialogue and partnership. First of all, a common strategy should be developed in cooperation between representatives of the administration responsible for action plans and entrepreneurs experienced in eliminating online threats. Second, it concerns operational activities undertaken by network administrators of public administration offices and their counterparts in private companies. However, this must not be simply superficial dialogue. The EU and its Member States need to devise a coherent system of protection, based on standards applicable to entities affected by cybersecurity (de facto, each and every one of us). Protection in cyberspace cannot be provided in isolation from the outside world[1].

Characteristics of the Visegrad Group countries

The Visegrad Group (V4) is an association of four Central European countries. The original reason for its establishment was to provide a platform on which to cooperate regarding the withdrawal of Soviet troops stationed in Central and Eastern Europe. Subsequently, the V4 played an important role in the coordination of efforts to join NATO and the EU. Today, the Group’s objective is to further develop a partnership between these countries and to coordinate their positions on major international issues, including those within the EU. The Group was set up on 15 February 1991 by three countries: Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, creating the so-called Visegrad Triangle. Following the split of Czechoslovakia into two countries on 1 January 1993, the Czech Republic and Slovakia became members of the Group. The International Visegrad Fund is an institution established to finance joint projects.

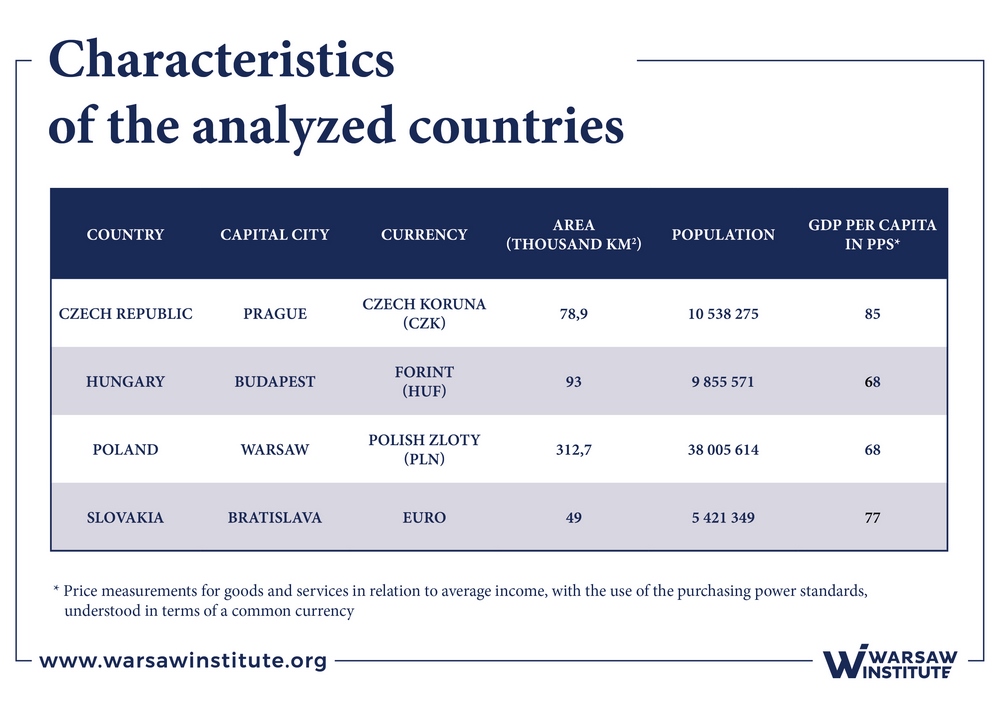

All four countries joined the European Union on 1 May 2014 and have belonged to the Schengen zone since 21 December 2007. Slovakia adopted the euro on 1 January 2009, while the others chose to keep their national currencies.

Taking into account the living standards in the analyzed countries, defined as GDP per capita expressed in PPS, the Czech Republic (85) and Slovakia (77) perform best, while Poland and Hungary are at the same level (68). In terms of area, Poland is the largest country, and Slovakia the smallest. This is also true as of population size. All of the countries are parliamentary republics.

Cybersecurity System of the Visegrad Group countries

In Poland, the issues of its cybersecurity system have been addressed in the following documents:

- Act of 26 April 2007 on crisis management (the Official Journal of Laws of 2007 No. 89 item 590, as amended), in which Article 3 item 2 defines critical infrastructure to be a system of interconnected facilities, including construction facilities, equipment, installations, and services essential to the safety of the state and its citizens and ensuring efficient functioning of public administration bodies, as well as institutions and businesses. Critical infrastructure includes the following systems: energy supply, energy and fuel raw materials, communications, ICT networks, financial, food supply, water supply, health protection, transport, and rescue, all of which ensure the continuity of public administration, production, storage, and the use of chemical and radioactive substances, including pipelines of hazardous substances.

- Act of 5 August 2010 on the protection of classified information (the Official Journal of Laws 2010, No. 182, item 1228, as amended) and Act of 18 July 2002 on the provision of electronic services (the Official Journal of Laws 2002, No. 144, item 1204, as amended), in which an ICT system was defined, which should be understood as a set of interconnected IT devices and software that ensures the processing and storage, and the sending and receiving of data via telecommunications networks with a terminal device appropriate for a given type of telecommunications network, as defined in the Act of 16 July 2004.

- Telecommunications Law (Journal of Laws of 2016, item 1489, as amended).

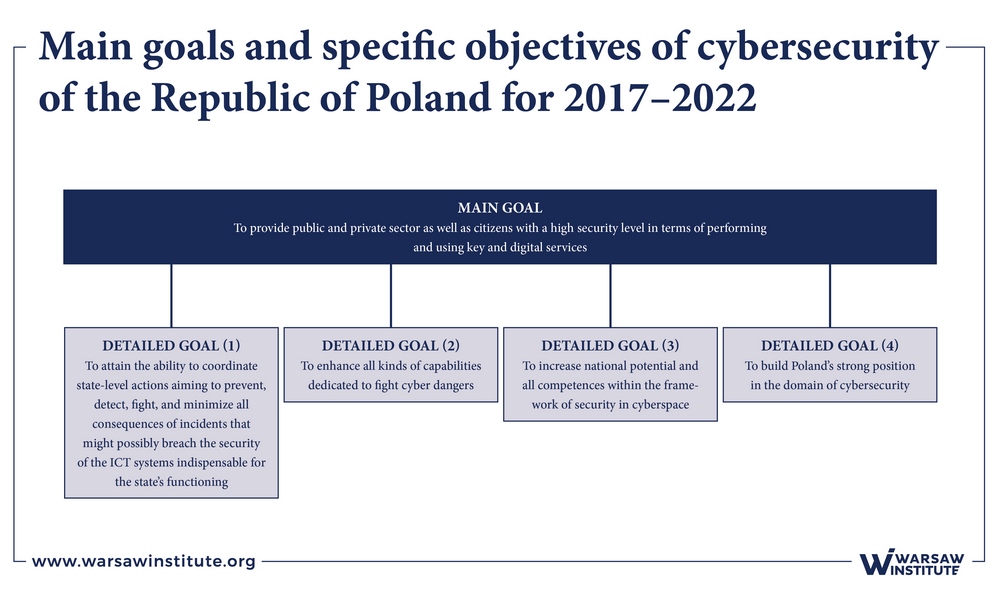

- National Framework for the Cyber Security Policy of the Republic of Poland for the years 2017–2022 (Resolution No. 52/2017 of the Council of Ministers of 27 April 2017) and the Cyber Security Strategy of the Republic of Poland for the years 2017– 2022, in accordance with the Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council (EU) on measures for a common level of high security of networks and information systems within the territory of the Union (EU OJ 2016 L194), which remain closely related. These were developed by a group consisting of representatives of the following ministries: digitization, national defense, internal affairs and administration, as well as representatives of the Internal Security Agency, the Government Centre for Security and the National Security Bureau. In accordance with the vision contained in point 4, in 2022, Poland will be a country more resilient to cyber-attacks and threats. Thanks to the synergy of internal and international activities, the cyberspace of the Republic of Poland will constitute a safe environment enabling the implementation of all state functions and allowing for the full exploitation of the potential of the digital economy, while respecting the rights and freedoms of citizens”.

The main as well as specific objectives of the Strategy are presented in Figure 2.

On 26 April 2018, the Council of Ministers adopted a draft act on the national cybersecurity system which aims to implement the NIS directive effective as of 25 May 2018. The Act provides for, inter alia:

- the creation of three CSIRTs[2]: Gov[3], MON[4] and NASK[5];

- rules for identifying the operators of key services and their obligations,

- implementation of a safety management system and conducting audits),

- rules regarding public entities (these will be obliged to handle incidents),

- requirements for digital service providers (online trading platforms, cloud computing

- services and search engines),

- a description of the incident response system and the involvement of all stakeholders,

as well as the categories of incidents.

In March 2018, the Office of the Government Plenipotentiary for Cyber Security[6] was established. Pursuant to § 2 of the Regulation, the plenipotentiary is the Secretary of State or the Undersecretary of State in the Ministry of National Defense. The tasks of the Plenipotentiary include ensuring the coordination of activities and implementation of the government’s policy in the area of ensuring cybersecurity, and in particular:

- analysis and assessment of the state of cybersecurity on the basis of aggregated data and indicators developed with the participation of government administration bodies and teams responding to computer security incident operating in the Ministry of National Defense, the Internal Security Agency and the Scientific and Academic Computer Network – National Research Institute;

- developing new solutions and initiating activities in the field of cybersecurity at the national level;

- issuing opinions on drafts of legal acts and other government documents affecting the implementation of tasks in the field of cybersecurity;

- conducting and coordinating activities conducted by government administration bodies aimed at raising public awareness of the threats of cybersecurity and safe use of the Internet;

- initiating national cybersecurity exercises; and

- cooperating with other countries, organizations and international institutions on cybersecurity issues;

- undertaking activities aimed at supporting scientific research and the development of technologies in the field of cybersecurity;

– in consultation with relevant ministers.

On February 16, 2015, the Government of the Czech Republic approved the new National Cybernetic Security Strategy for the years 2015–2020, which is a comprehensive set of measures aimed at achieving the highest possible level of cybersecurity in the Czech Republic.

The main objectives to be achieved in five years are a key part of the strategy. They are divided into the following priority areas:

- Ensuring efficiency and strengthening of all structures, processes and cooperation in the field of cybersecurity.

- Active international cooperation.

- Protection of the national Critical Information Infrastructure and Important Information Systems.

- Cooperation with the private sector.

- R&D/Consumers’ trust.

- Support to the education, awareness and development of the information society

- Support to the development of the police’s capabilities to investigate and prosecute information crime.

- Cybersecurity legislation (development of legislative framework). Participation in the creation and implementation of European and international regulations[7].

The National Agency for Cyber Security and Information has been

operating since August 2017. The concept of cybersecurity of the Slovak Republic for the years 2015–2020 was implemented on June 1, 2015.

The concept is based on a statement and a description of the basic terms and principles, characteristics of the current situation of the strategic, legal and institutional frameworks in the area of cybersecurity in the Slovak Republic and on a strategic and methodological framework formed by NATO and European Union documents; subsequently, the concept formulates principles, goals and proposed solutions[8].

They are divided into the following objectives:

- Citizens’ awareness.

- Critical Information Infrastructure Protection.

- Engage in international cooperation.

- Establish a public-private partnership.

- Establish an incident response capability.

- Establish an institutionalized form of cooperation between public agencies.

- Establish baseline security requirements.

- Establish incident reporting mechanisms

- Foster R&D.

- Organize cybersecurity exercises.

- Strengthen training and educational programs[9].

In June 2015, the government set up a National Security Office for cybersecurity. The

National Agency for Electronic Networks and Systems is also in place.

On March 21, 2013, the Hungarian government decided on a national cybersecurity

strategy (No. 1139/2013).

The purpose of the strategy is to determine national objectives and strategic directions, tasks and comprehensive government tools which will enable Hungary to enforce its national interests in the Hungarian cyberspace, within the context of the global cyberspace[10].

They are divided into the following objectives:

- Critical Information Infrastructure Protection.

- Develop national cyber contingency plans.

- Engage in international cooperation.

- Establish an incident response capability.

- Establish an institutionalized form of cooperation between public agencies.

- Establish baseline security requirements.

- Establish incident reporting mechanisms.

- Organize cybersecurity exercises.

- Strengthen training and educational programs[11].

It is worth noting that in 2018 two legal acts entered into force in all countries belonging to the European Union:

- on 10 May – Directive 2016/1148 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2016 on measures for a high common level of network and information system security within the Union, which requires Member States to develop national strategies for network and information system security or to set up appropriate monitoring and risk response units.

- on 25 May – Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR). The Regulation covers all entities, both public and private, that process personal data and, at the same time, most of the data processing operations.

Expenditure on cybersecurity of the Visegrad Group countries

A state’s expenditure on cybersecurity is difficult to estimate. Costs calculated at the state level are scattered across different areas such as digital technologies, digitization, development, economy, science, security and defense, thus making it difficult to determine exact values. There are no comprehensive statistics that cover cybersecurity expenditure at different levels.

The analysis of expenditures on cybersecurity of the Visegrad countries was made on the basis of selected indicators:

- defense spending;

- defense spending as % of GDP;

- R&D expenditure as % of defense expenditure;

- ICT sector as % of GDP;

- employment in the ICT sector;

- employment in fields related to science and technology;

- number of ISO/IEC 27001 certificates issued;

- ICT Development Index (ITU);

- IMD World Digital Competitiveness (WDC);

- National Cyber Security Index (NCI);

- The difference shows the relationship between the NCSI score and DDL.

Selected indicators indirectly demonstrate a state’s preparedness to finance cybersecurity.

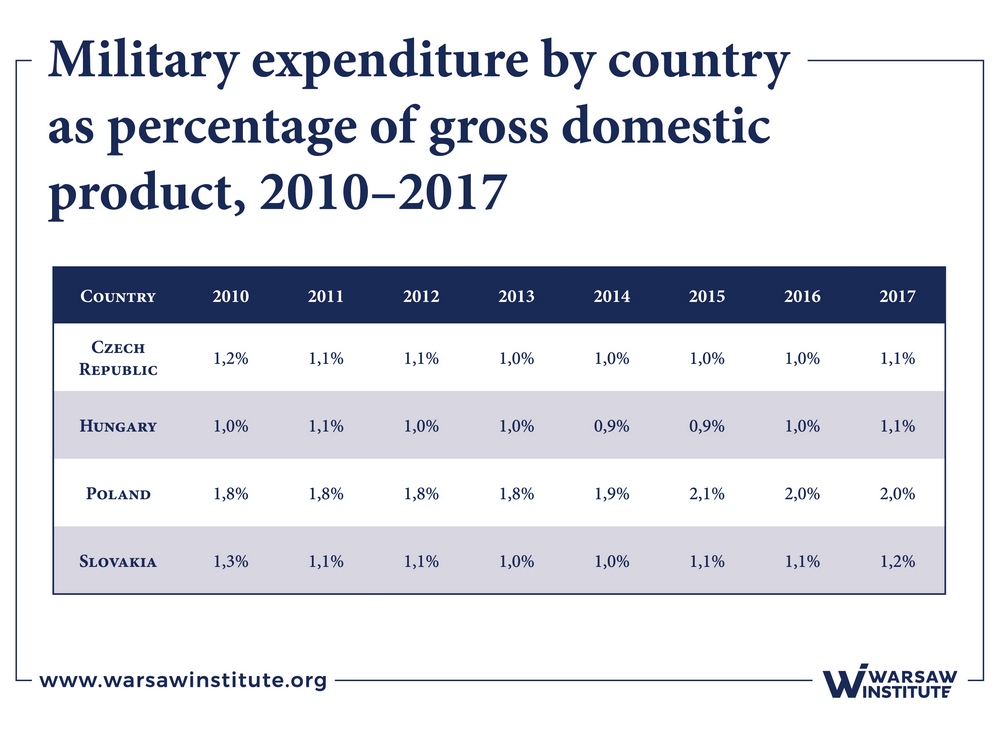

Table 2 presents defense spending. Table 3 shows the level of defense spending as a percentage of GDP in 2010–2017.

An analysis of the data presented in the table shows that in 2017, defense spending in each country increased compared to 2016. The highest increase was recorded by the Czech Republic (14%) and the lowest by Poland (9%) (Note that absolute numbers should be taken into account – and here, it is Poland that takes the lead in this type of expenditure).

Only Poland allocates at least 2% of its GDP to this purpose, in accordance with NATO guidelines. In other countries, the level of defense spending is approximately 1%.

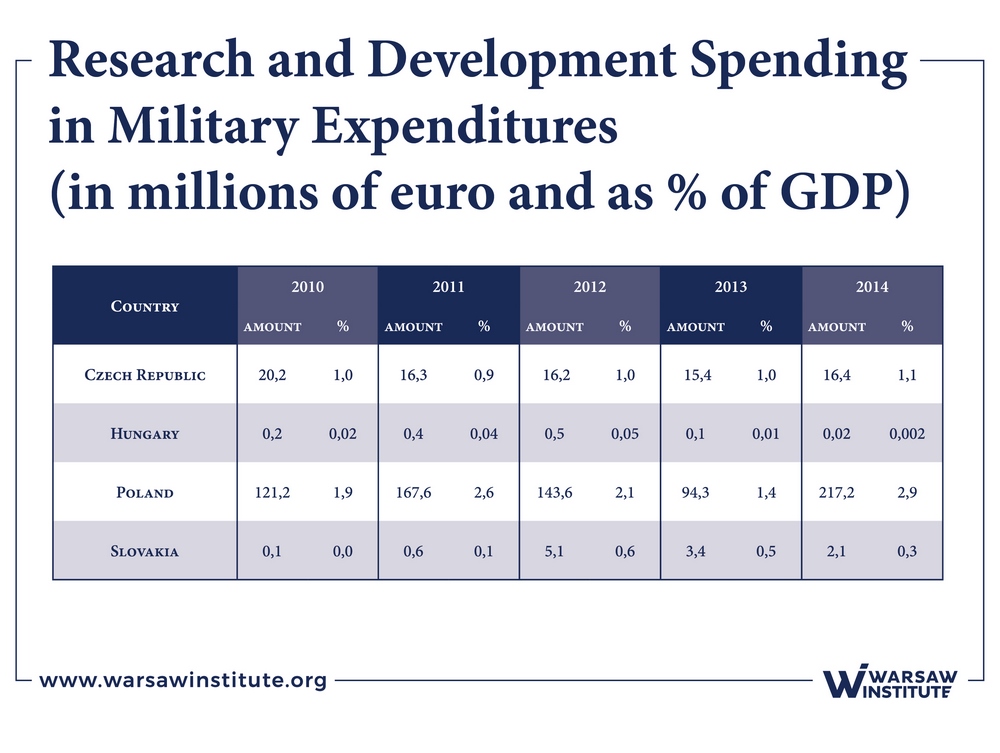

Table 4 shows R&D expenditure as a share of defense spending in 2010–2014.

Analyzing overall defense spending in 2014, the Czech Republic (6,5%) recorded a decrease compared to the previous year, while the other countries recorded an increase (the largest made by Poland – 12,6%).

Poland allocates a significant part of its defense budget on research and development.

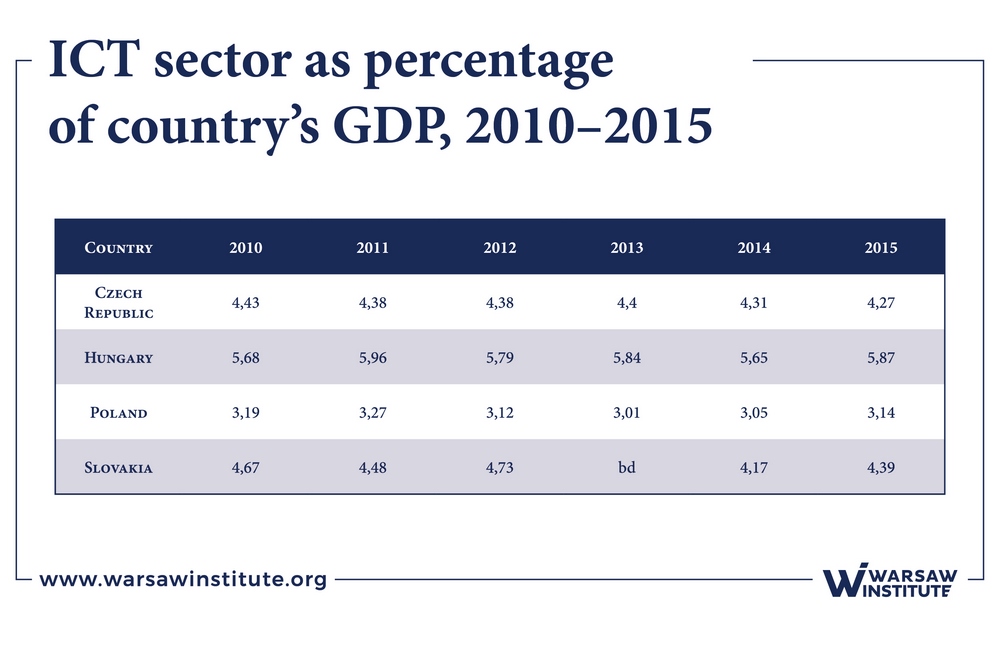

Table 5 presents the share of the ICT sector in GDP in selected countries for the years 2009–2015.

Analyzing the data in Table 5, it can be observed that Hungary recorded a high share of ICT above 5% between 2010 and 2015. The share of the ICT sector in the GDP of the Czech Republic and Slovakia is above 4%. The share of the ICT sector in Poland’s GDP is still relatively low, which may indicate a high potential for development. In Poland, this sector translated into 3,14% of GDP in 2015, while in countries such as Malta, Great Britain, Hungary, Bulgaria, Estonia the level is at 7,26%, 5,9%, 5,87%, 5,08%, and 4,81% respectively.

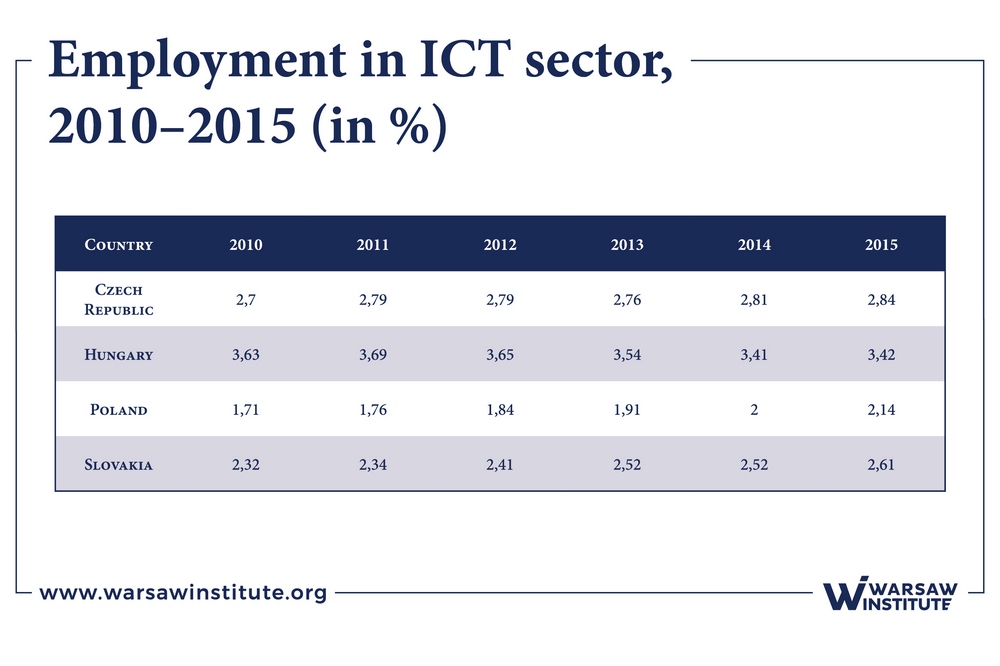

Table 6 illustrates employment in the ICT sector in 2010–2015 and Figure 1 shows employment in science and technology related areas in 2016 (as a % of the active population aged 25–64).

The analysis of Table 6 shows that Hungary has the highest level of employment in the ICT sector, exceeding 3%; whereas for Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic this accounts for less than 3%.

Analysis of Figure 1 shows that the highest level of employment in science and technology (42,8%) was recorded by Poland and the lowest by Slovakia (34,2%).

On 10 January 2018, the standard PN-EN ISO/IEC 27001:2017-06 “Information security management systems. Requirements” was issued. This standard does not introduce new requirements for PN-ISO/IEC 27001:2014-12, and this update results from the introduction of previously issued corrections to ISO/IEC 27001:2013: Cor 1:2014 to Annex A Clause 8.1.1 and Cor 2:2015 to Clause 6.1.3.

ISO/ IEC 27001 (PN-ISO/ IEC 27001) “Information Security Management Systems. Requirements” is the basis for the certification of the information security management system.

The ISO/IEC 27001 standard has international scope, and defines the requirements and principles of initiating, implementing, maintaining and improving information security management in an organization. It also includes best practices for the application of security objectives in the areas of information security management.

In 2016, the ISO 27001 certification market grew globally by 25% y/y. According to Przemysław Szczurek, Product Manager for Information Security TUV NORD Polska, the main reasons encouraging a certification of information security management system are as follows:

- improving the security of our own information, as well as information entrusted to us by our business partners,

- increasing a company’s value,

- establishing a competitive advantage[12].

By analyzing the data covering a period of seven years, it can be seen that the largest number of certificates has been issued in Poland: in 2016 alone, as many as 657 certificates were issued in Poland. Comparing to 2015, this represents an increase of 47%. Globally, Poland ranks 11th. The largest number of certificates is issued in Japan, where in 2016 the number of certificates issued was 8,945, followed by the United Kingdom with 3367. Within Visegrad countries, Poland takes the lead. In the Czech Republic, the highest number of certificates was issued in 2010 (529), in Slovakia in 2015 (232, a drop of 9% y/y in 2016), and in Hungary in 2016 (421, a 33% y/y increase). In terms of industry, information technologies take first place, with the number of certificates in 2016 amounting to 6,578 (the public administration sector ranks 7th, with 235 certificates issued).

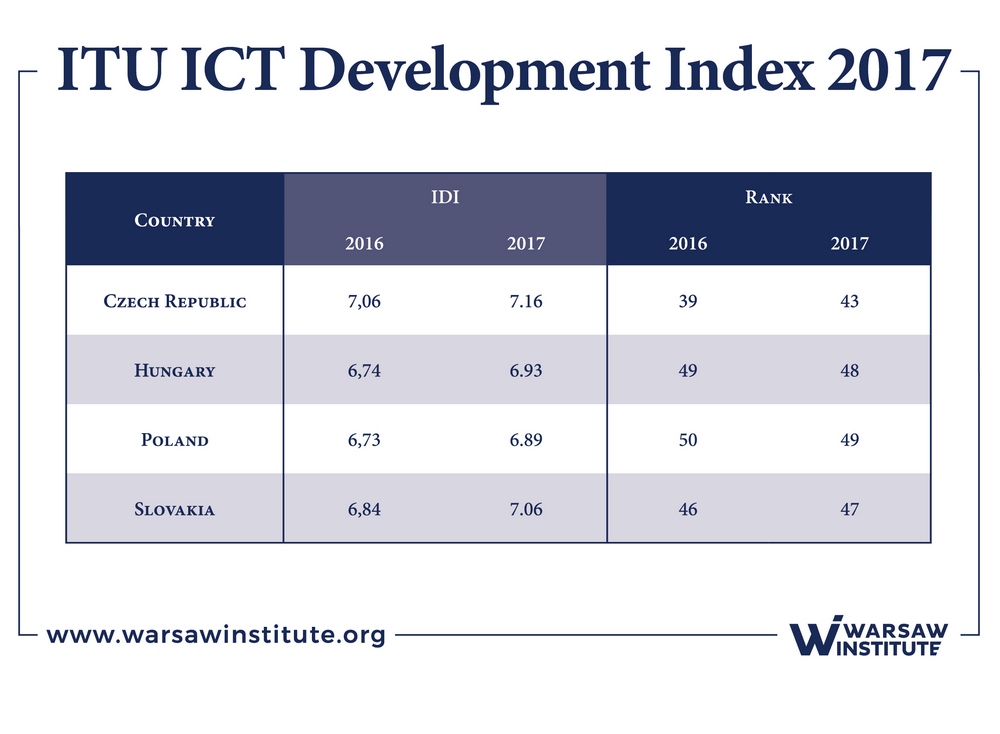

The ICT Development Index of the International Telecommunication Union is one of the most trusted indicators in the world reflecting a given society’s and economy’s reliance on ICT technologies. Indirectly, it also indicates the technological advancement of individual countries, which in turn translates into the level of awareness of threats in the cyber field, i.e. the readiness to bear the costs of strengthening cybersecurity.

In 2017, the ITU issued a second edition of the index (the first one was published in 2014). The indices in both reports are based on the same pillars:

- legal basis – with an emphasis on forensic science and the fight against cybercrime;

- operational capacities – comparable to the EU index;

- organizational measures – so-called road maps, policies, procedures, evaluation systems;

- reinforcement of the capacity of the state – standardization of development, development of professional staff, certification;

- cooperation between countries, agencies, sectors and within the framework of interstate organizations.

Analyzing the data shown in Table 8, in 2017, the index (+7) was reached by the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and (-7) by Hungary and Poland.

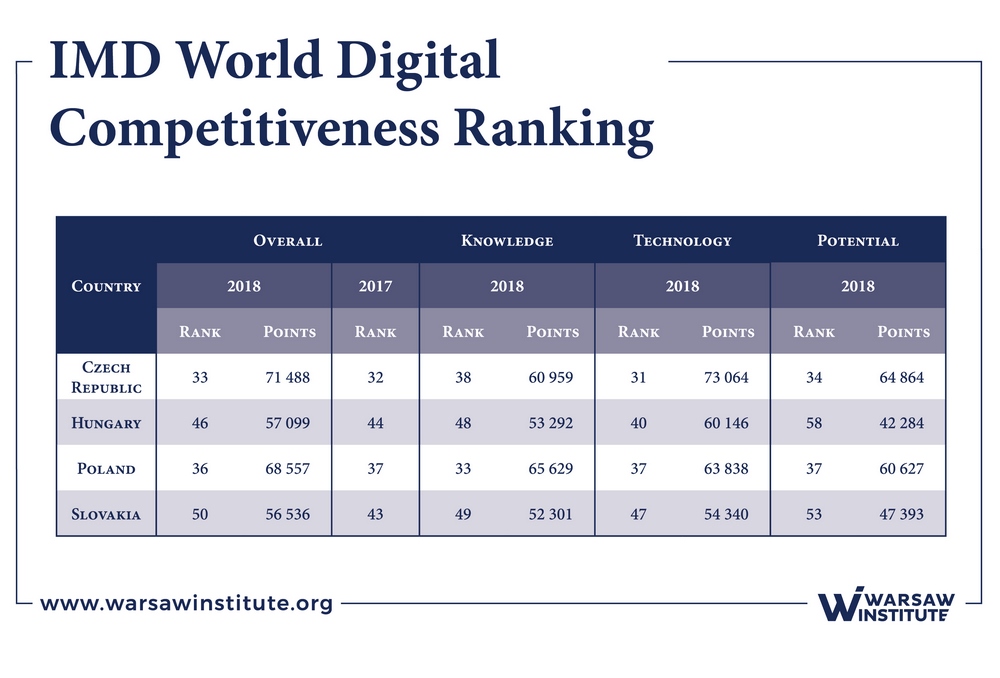

In 2018, a separate report assessing the “digital” competitiveness of countries was published by the International Institute for the Development of Lausanne Management (IMD World Competitiveness Center) for the second time.

The IMD World Digital Competitiveness (WDC) ranking analyzes and ranks countries’ ability to adopt and explore digital technologies leading to transformation in government practices, business models and society in general. Based on research, the methodology of the WDC ranking defines digital competitiveness into three main factors: knowledge, technology, future readiness[13].

Out of the 63 countries surveyed, the Czech Republic ranked 33rd with 71,488 points (out of 100,000 possible achieved by the United States which was ranked first). The rest of the Visegrad Group was ranked as follows:

- Poland ranked 36th (in 2017: 37th) scoring 68,557;

- Hungary ranked 46th (in 2017: 44th) scoring 57,099;

- Slovakia ranked 50th (in 2017: 43rd) scoring 56,536.

The National Cyber Security Index (NCSI) is a global index, which measures the preparedness of countries to prevent cyber threats and manage cyber incidents. The NCSI is also a database with publicly available evidence materials and a tool for national cybersecurity capacity building. The indicators of the NCSI have been developed according to the national cybersecurity framework. The NCSI Score shows the percentage the country received from the maximum value of the indicators. The maximum NCSI Score is always 100 (100%) regardless of whether indicators are added or removed[14].

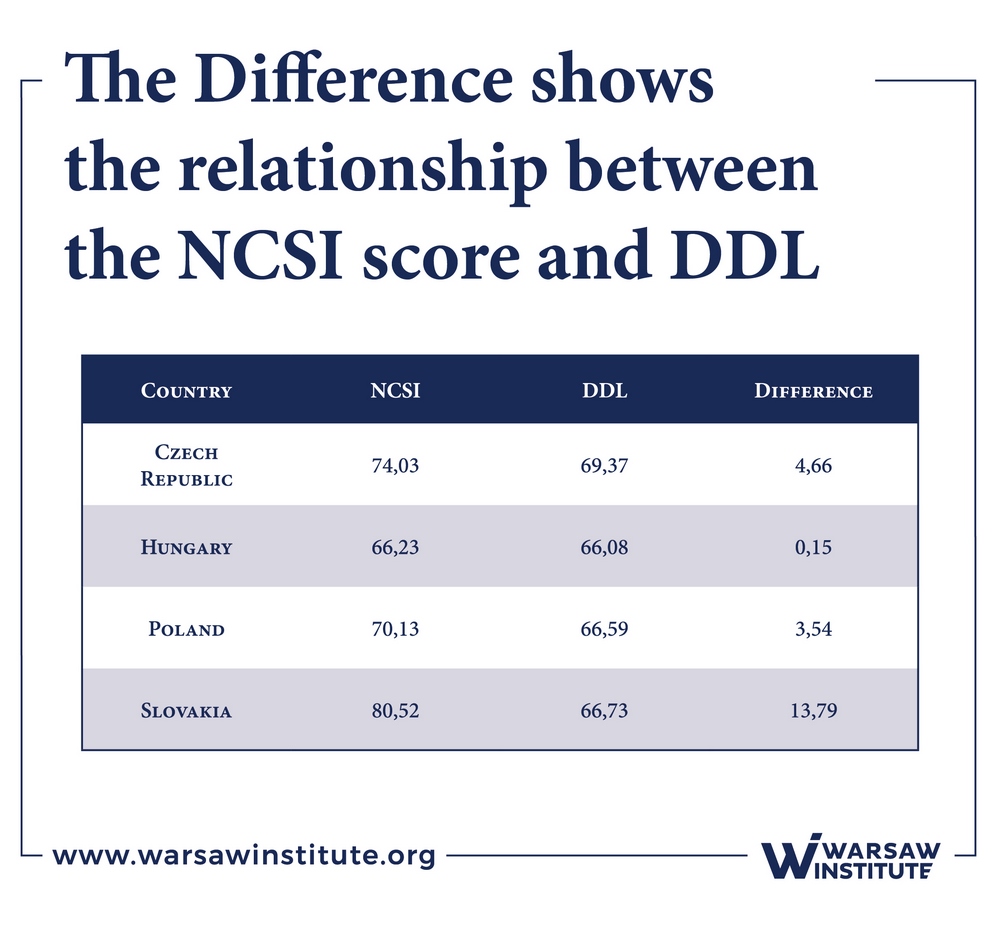

In addition to the NCSI Score, the index table also shows the Digital Development Level (DDL). The DDL is calculated according to the ICT Development Index (IDI) and Networked Readiness Index (NRI). The DDL is the average percentage the country received from the maximum value of both indexes. The difference shows the relationship between the NCSI score and the DDL. A positive result shows that the country’s cybersecurity development is in accordance with, or ahead of, its digital development. A negative result shows that the country’s digital society is more advanced than the national cybersecurity area[15].

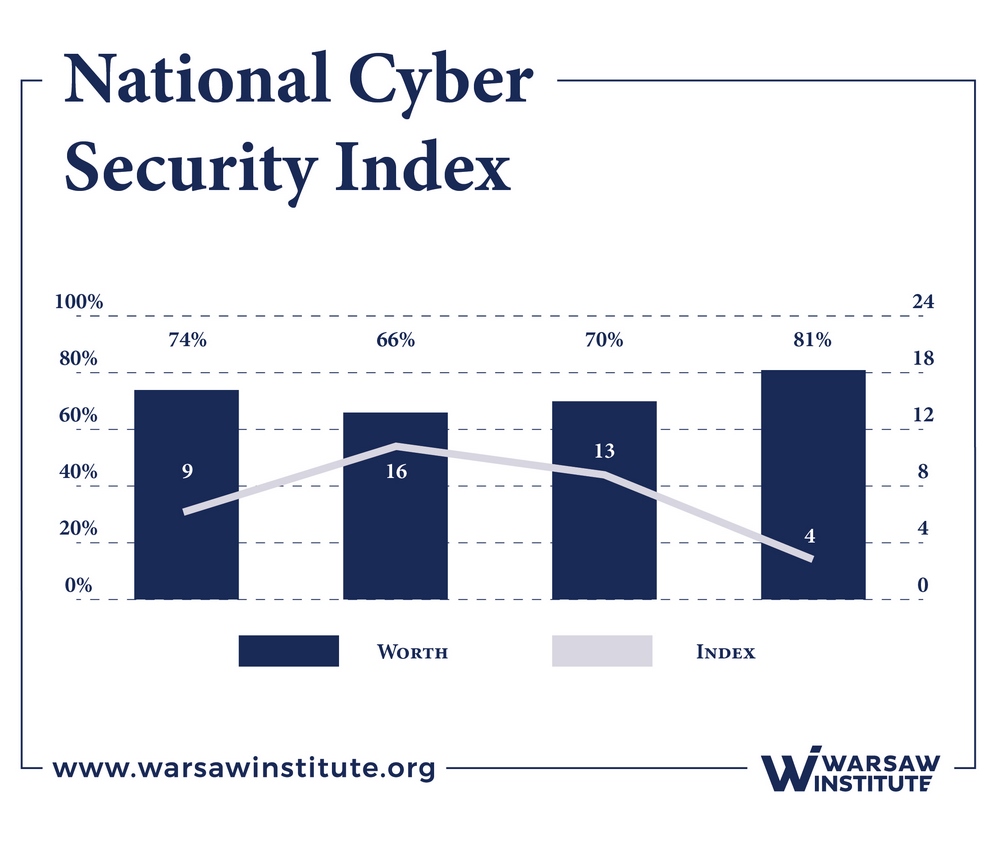

Chart 2 illustrates the current NCI Index, and Table 10 the difference between NCSI and DDL results.

Slovakia is ranked 4th in the NCSI, which measures a state’s preparedness to prevent cyber threats and to manage cyber incidents, with a relatively high score of 80,52% (France is ranked first, with 83,12%). The other Visegrad Group countries were in the top 20 places:

- Czech Republic ranked 9th, scoring 74,03%;

- Poland ranked 13th, scoring 10,13%;

- Hungary ranked 16th, scoring 66,23%.

The Visegrad countries have exhibited positive results, which mean that the development of cybersecurity is in line with the digital development in each country.

To recapitulate the results of the comparison of indicators for selected countries, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- there is a continuous need for an ongoing analysis of expenditure versus costs/threats on a national scale (public and private sector, support for science for ICT security and for the development of the society/digital economy);

- a cost/threat analysis should be linked to a single cybersecurity think-tank that would coordinate actions (and hence expenditure) across the country;

- the Visegrad Group countries have evinced relatively good cybersecurity potential.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The above analysis has proved that the identification of cybersecurity spending ceilings is not a simple operation. It appears that governments, public institutions and private entities all lack an appropriate tool, which would help to assess risks and threats (in the short-, medium- and long-term perspective), develop strategies and programs to counter these risks and, in so doing, allocate appropriate resources.

There is a need for a systemic coordination on a national scale in order to effectively analyze the need for expenditure and to minimize costs on a national scale. It is necessary for authorities to be informed of the costs incurred by the private sector. Conclusions from this analysis should influence an efficient building of our own national potential at the scientific, technical and industrial level in order to ensure overall cybersecurity.

A well-designed decision-making structure is key to a rational and more effective government policy of expenditure on cybersecurity, both at the national and private levels. At the national level, it is necessary to specify competencies in three areas: detecting, protecting and responding to threats at all levels of government, simultaneously initiating and coordinating actions at all levels.

In 2012, the Kosciuszko Institute published V4 Cooperation in Ensuring Cyber Security – Analysis and Recommendations, in which the following recommendations were put forward, which are still valid:

- Common understanding of the fundamental cybersecurity framework needs to be ensured. The process includes, among others, consideration of key players, definition of basic notions and fundamental security goals as well as limitations which need to be respected (e.g. privacy preservation).

- There is a strong need for public-private cooperation within each of the V4 countries as well as on the level of cross-national sectoral working groups. Additionally, private entities should be strongly involved in the process of cyber space protection.

- The V4 countries should support the involvement of the private sector in Cyber Europe exercises and exercises organized by NATO.

- The V4 countries should jointly explore the utility for the benefits of regional cooperation on cybersecurity, the mechanism offered by European treaties such as permanent structured cooperation, and the EU’s provision to a task undertaken by several Member States.

- The V4 countries should support the inclusion of the provisions related to cyber threats in the new edition of the European Security Strategy.

- There is a need for establishing a new comprehensive EU cybersecurity strategy that would encompass all the dimensions of the EU’s action in this field.

- The V4 Group should support establishing a body (e.g. EU Cyber Security Coordinator) for the purposes of coordinating various aspects of the EU’s cybersecurity policy. Alternatively, the responsibilities of the above-mentioned entity can be attributed to an already existing structure.

- Developing a CSDP doctrine on cyberwar that would encompass the issue of information operations and would be compatible to relevant NATO procedures is recommended.

- The V4 Group should postulate the inclusion of funding tasks related to cybersecurity into various EU’s funding mechanisms (e.g. cohesion policy)[16].

In conclusion, it may be stated that in terms of both tangible expenditure on research, as well as in respect of the organization and effectiveness of the cybersecurity system, the Visegrad Group countries are more or less in the vicinity of the EU average. A successful coordination both within and among the V4 countries may lead to the development of a specialization of these countries in the field of cybersecurity (although competition is high – from large countries such as Germany or France, to the Netherlands, to smaller but advanced countries in this field such as Estonia or Lithuania). This can promote good use of the International Visegrad Fund programs and the Group’s efforts to create even broader cooperation forums – such as the Three Seas Initiative[17]. All of the above activities are related to a readiness to incur expenditure on building efficient structures, both in respective countries and internationally, increasing expenditure in the field of ICT and on R&D (and its implementation), as well as on initiating international programs under V4, the Three Seas Initiative, the EU or NATO.

[1] Cyberbezpieczeństwo – problem nas wszystkich? Strategie państw UE wobec wyzwań związanych z dostępem do danych w sieci, „Europejskie Forum Nowych Idei” [trasl. Cyber security – a problem affecting us all? Strategies undertaken by the EU Member States with regard to challenges posed by accessing online data, from: European Forum for New Ideas], Sopot, October 1, 2015, p. 1.

[2] CSIRT – Computer Security Incident Response Team operating at the national level.

[3] CSIRT GOV – Computer Security Incident Response Team led by the Head of the Internal Security Agency.

[4] CSIRT MON – Computer Security Incidents Response Team led by the Minister of National Defence.

[5] CSIRT NASK – Computer Security Incident Response Team run by the Scientific and Academic Computer Network – National Research Institute.

[6] Resolution of the Council of Ministers of March 16, 2018 on the appointment of the Government Plenipotentiary for Cyber Security, Journal of Laws of March 20, 2018. Item 587.

[7] Vide: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/about-enisa/structure-organization/national-liaison-office/news-from-the-member-states/czech-republic-national-cyber-security-strategy-2015-2020, (accessed on: August 19, 2018 r.).

[8] Cyber Security Concept of the Slovak Republic for 2015–2020, p. 6.

[9] Vide: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/national-cyber-security-strategies/ncss-map/strategies/cyber-security-concept-of-the-slovak-republic, (accessed on: August 19, 2018).

[10] National Cyber Security Strategy of Hungary, p. 2.

[11] Vide: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/national-cyber-security-strategies/ncss-map/strategies/national-cyber-security-strategy, (accessed on: August 19, 2018).

[12] Market Analysis Report_ISO_27001.pdf, p. 3.

[13] IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2018, p. 28.

[14] Vide: https://ncsi.ega.ee/methodology/ (accessed on: August 17, 2018).

[15] Vide: https://ncsi.ega.ee/methodology/ (accessed on August 10, 2018).

[16] T. Rezek, T. Szatkowski, J. Świątkowska, J. Vyskoč, M. Ziarek, V4 Cooperation in Ensuring Cyber Security – Analysis and Recommendations, The Kosciuszko Institute, Kraków 2012, s. 83–87.

[17] More on this topic in: BRIEF OF THE PROGRAMME OF THE Kosciuszko INSTITUTE, The Digital 3 Seas Initiative – The Digital Tri-City Initiative is a step into the future of the region, June 2018.

_________________________________

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.