SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 29 May 2019

Conference Report – Western Balkans: Infrastructure, Energy, Geopolitics

Conference report containing an extensive description of infrastructural and energy issues while focusing on the influence of crucial international actors in the Western Balkan region. The following report is a part of an international conference “Western Balkans: Infrastructure and Energy from a Geopolitical Perspective” that took place in Warsaw on May 29, 2019. The event was part of the official program of Poland’s presidency of the Berlin Process and served as a preparatory meeting for the 2019 Western Balkans Summit in Poznań.

INTRODUCTION

Viewed as a European enclave, the Western Balkan region has recently aroused interest of many international actors, both regionally (the European Union, Turkey, and Russia) and globally (China and the United States).

Although the Balkan countries constituted an economic unity back in the times of Yugoslavia, their economic ties loosened after the end of the Balkan war in the 1990s. Almost thirty years have passed since the breakup of Yugoslavia and the restoring of international relations by its former states; the region has yet again been unified by an ongoing process of their integration with the European Union.

The following report makes an attempt to explain the situation in the Western Balkans while examining the involvement of individual global actors in the region. First, attention is drawn to the regional road, railway, aviation, and maritime infrastructure, especially in the cross-boundary context. Secondly, the report outlines the issues of energy and raw material security, focusing on external energy dependence and the development of alternative energy sources. Ultimately, and of consequence, both themes are linked to geopolitical aspects and the competition of superpowers in the Western Balkans.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Located in a strategic European region at the crossing of trade routes from West to East and from South to North, the Western Balkans is an essential area for investments. Time delays in building road, railway, maritime, and aviation infrastructure pose a challenge for the integration of the Western Balkan countries, or the economic reintegration when speaking of the former Yugoslav states. The greatest challenge consists in selecting the best path of development and balancing infrastructure expenditure, especially in the regional dimension. To build infrastructure, especially routes, the Western Balkans remains dependent on loans granted by both the European Union and a group of individual states. Each of these entities has its own investment mechanism in the region. From the EU perspective, developing infrastructure in the Western Balkan region is aimed at integrating the Western Balkans with the Community, achieving the progress in political stabilization after the 1990s wars and addressing all emerging needs of this European region. When investing money in the area, China yet pays little attention to crucial EU factors, such as transparent tendering procedures or a democratic scoreboard for the Western Balkans. For their part, both Russia and Turkey focus on implementing specific infrastructure projects in a bid to strengthen their political and economic influences on Balkan soil.

Maritime infrastructure

Among the Western Balkans countries that have access to the Sea are Albania, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the last of which has a 20-kilometer coastal strip. The main port in the region are Montenegro’s Bar, a ferry route linking the country with Italian harbors, also in Bari, as well as Albania’s Durres, served by regular ferries from Italy-based ports of Ancona, Bari and Trieste. Located between principal Croatian international harbors in Split and Dubrovnik, Bosnia’s port of Neum primarily fulfills a local function and does not handle international connections.

Aviation infrastructure

Albania’s only international airport is Tirana International Airport while work is currently underway to construct the airport in the southern Albanian city of Vlora. The investment is being carried out by Turkey’s Cengiz Construction company, also involved in the construction of Istanbul’s new airport. In 2018, Tirana airport handled 2.5 million passengers[1]. It serves regular flights to Western Europe and Turkey yet there exist no intercontinental connections.

Bosnia’s major airports are located in Banja Luka and Sarajevo, the former of which recorded a sharp rise in passenger traffic in 2018 after low-cost airline Ryanair commenced operations to the city on three routes. As estimated by the authorities of the airport, the facility should welcome over 100,000 passengers in 2019, a fourfold increase compared to 2018[2]. In 2018, Sarajevo Airport handled for the first time a combined total of 1 million passengers. Bosnian airports serve regular flights to Western European countries and Turkey. Talks are currently underway to open connections to Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia[3].

Serbia boasts of two international airports in Belgrade and Niš. The former offers regular flights to most European states and New York (since 2016). Referred to as the largest in the Western Balkans region, Belgrade Airport welcomed 5.2 million passengers in 2018[4]. Niš Airport handled about 350,000 passengers in 2018[5].

Montenegro’s two international airports are located in Tivat and the capital city of Podgorica, both of which can handle approximately 1 million passengers per year. Such a considerable number of travelers is linked to tourism, including connections from and to Russia whose citizens are entitled to travel to Montenegro without a visa.

Kosovo’s only international airport is located in the capital city of Pristina; In 2018, it welcomed 2 million passengers[6]. It serves regular flights to Western Europe and Turkey.

North Macedonia has two international airports in Skopje and Ohrid, the former of which welcomes annually approximately 2 million passengers while the latter – 150,000.[7] North Macedonia, similarly to other countries of the region, handles flights to Western Europe and Turkey.

Rail infrastructure

Albania has no international passenger rail connections and has an only international network that transports freight to Montenegro. Albania’s primary railway line runs from the northern city of Shkodra to Vlora, located near the Greek border. With €650 million grant funding allocated for 2014–2020, the European Union is the largest donor in Albania. Those funds are dedicated for infrastructure, as well as public administration, fight against crime and justice, water supply and sewerage sector, social inclusion and employment sector.

Due to the country’s internal division into statelets – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska – Bosnia’s railway connections are operated by two independent companies. The former’s running train lines are Doboj via Sarajevo to Ploce while Republika Srpska operates on the route Doboj–Banja Luka–Novi Grad. The total length of railway connections in Bosnia and Herzegovina is 1031 km. Also, Bosnia and Herzegovina boasts of international railway connections with Zagreb, Belgrade and Budapest, all of which are yet temporarily suspended due to the reconstruction works.

Montenegro’s two railway lines run from Serbia to the city of Bar (of a total length of 249 km) and connect Nikšić and the country’s capital Podgorica as well as Lake Shkodra (56 km). Although the latter line also heads to Albania, it serves to handle freight trains only. There are four separate companies that operate within the Montenegrin railway system[8].

Kosovo’s railway network connects most of the country’s cities. The main EU-funded railway infrastructure initiative provides for building a Pan-European transport corridor running from Kosovo to Serbia and North Macedonia[9]. The major challenge is, however, to upgrade the existing railway lines, enabling to speed up trains whose current speed does not exceed 50 kilometers an hour.

North Macedonia’s railway links head to the country’s all major cities. Also, through North Macedonian territory passes a crucial international railway link connecting Serbia’s Belgrade and Greece’s Thessaloniki. The country also boasts of railways links with Sofia (Bulgaria) as well as linking Skopje and Kosovo. The total length of North Macedonia’s railway lines amounts to 683 km[10] while that of Serbia – 3,809 km. A key route linking the south and the north runs both through Serbia and North Macedonia, from Budapest via the North Macedonian border to the Greek port of Thessaloniki. The Serbian government has declared its intention to loan €440 million to upgrade the country’s railway infrastructure further, considering Russia-based firms as potential borrowers. Besides, Russian Railways helped Serbia to modernize the latter’s regional railway infrastructure[11].

Road infrastructure

Western Balkans regional road infrastructure projects are aimed at connecting this area with major European transport routes, with particular regard to international corridors. The total length of Albania’s roads is 18,300 km, including the country’s only motorway that is 177-kilometer long and runs from Tirana to the country’s border with Kosovo[12]. Bosnia and Herzegovina has 22,615 km of all roads, of which 3,800 are referred to as major, with 2,037 km in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBS) while 1,763 in Republika Srpska (RS). The country’s regional routes are 4,815- and 2,658-kilometer long in the FSBH and RS respectively while local roads account for 14,000 km, of which 5,520 in the FBH and 8,780 in RS[13]. The Montenegrin route network encompasses 7,000 km of roads, of which are 900 km of national routes, 950 km of regional roads and 5000 km of local roads[14]. North Macedonia has a road network of 20,000 km, including 216 km of highways and 906 km of national routes[15]. Kosovo’s road infrastructure dates back to the 1960s; the country’s road network consists of 647 km of main roads, 1,346 km of regional routes and 6,600 km of local roads[16]. The road network of Serbia is 40,845 km long, of which 415.7 km of highways with toll collection, 246.5 km of semi-highways with toll collection, 11,540 km of regional roads, and 23,780 km of local trails[17].

EU financing mechanisms for infrastructure investments

Compared to its Western European as well as Central and Eastern European peers, the Western Balkans has risen as a region that grapples with considerable delays in implementing infrastructure projects. As reported, regional infrastructure spendings remain at the level comparable to that of the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, which has come in the aftermath of wars and the slowdown in the region’s EU integration processes. First Western Balkan states are unlike to join the European Union sooner than until 2025. Infrastructure processes may yet be accelerated due to the Berlin Process. Launched in 2014, the initiative aimed to engage in infrastructure projects linking different parts of the region, with particular regard to building cross-border road connections that would overlap with transport corridors of particular economic importance.

In 2018, the European Union put into action its Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) program to bankroll infrastructure projects in the Western Balkans. The primary mechanism for upholding Western Balkan infrastructure investments is the Western Balkans Investment Framework (WBIF) whose primary goal consists in integrating funds from various sources, including individual states and the European Union (IPA). The WBIF [18]supports socio-economic development of the Western Balkans and their EU accession through the financial and technical assistance for strategic investments, particularly in infrastructure, energy efficiency, and private sector development. As a joint initiative of the EU, international financial institutions, bilateral donors, and the Western Balkans, the WBIF is a very successful platform representing an added value to the European perspective of the Western Balkans by supporting strategic investment projects and by strengthening regional cooperation and connectivity. With a value of €668 million (excluding cancellations and projects worth €7.9 billion), transport is one of WBIF’s most active sectors – the other vital sectors being the environment, energy, private sector development, social and digital infrastructure. It is worth mentioning that over the past ten years, the transport sector in the Western Balkans has attracted considerable investments.

The European Commission and the Western Balkans states became committed to improving the connectivity within the region and between the Western Balkans and the European Union. This was possible thanks to establishing in 2015 the Core Transport Network for the region and extending the EU Core Network Corridors. Only the projects which are part of the Network are eligible for investment grants as part of the Instrument of Pre-Accession Funds programs (IPA II). In the years 2015–2020, the European Union allocated grants of approximately €1 billion for connectivity projects. These initiatives are viewed as a crucial factor for growth and employment as they help to create more than 200,000 jobs and boost regional GDP growth. Also, the overall costs of the priority projects are estimated to be worth a total of €13.9 billion, the South East Europe Transport Observatory (SEETO) stated.

Also, the EU investment plan provides for expanding quays in the Albanian port of Durres under the TEN-T (Trans-European Transport) Core Network, worth a total of €27.7 million, expanding Bosnia’s three sections of the Mediterranean corridor running from the country to Croatia (€33.8 million), upholding investments between North Macedonia and Albania and North Macedonia and Bulgaria within the framework of the Via Carpatia project (€22.9 million[19]). In Montenegro, the EU-funded investment project will also build the €42.1 million Mediterranean corridor linking the country with Albania and Croatia and the €13.7 million Eastern railway link between Montenegro and Serbia. The EU’s support for Serbia generated around €41.4 million allocated for constructing a motorway to Kosovo as part of the Eastern corridor. In Kosovo, thanks to the Comprehensive Network in the road sector, the section of road towards the border with Albania has been completed and is fully operational, whereas the one from Kijevë to Zahaq – as part of the highway from Pristina to Peja/Peć connecting Kosovo and the Montenegrin border – is now in initial phase of implementation., The total project cost is estimated at around €155 million (excluding taxes and VAT), for which two loans have been obtained from the EBRD (€72 million) and the EIB (up to €80 million). The railway sector provides the Rehabilitation of Rail Route 10 project, as part of its comprehensive network. The overall cost of the project is €194 million, of which 50 percent is financed from the WBIF-sourced investment grants and the remaining 50 percent – from EBRD and EIB lending. The Orient/East-Med Corridor (R10 Rail Interconnection), which crosses Kosovo from the north to the south, from the border with North Macedonia to the one with Serbia, will allow for an increase in travel speed to 100 km an hour and ensure safe conditions for passenger and freight traffic.

Chinese infrastructure investments

China’s infrastructure investments in the Western Balkans are implemented as part of a broader political context within the 16+1 sub-regional cooperation platform encompassing the Baltic States, Central Europe, and the Balkans. Beijing’s strategy for the region consists of granting loans for infrastructure that could not be put into practice without foreign-sourced bankrolling. Though the European Union offers grants that are said to be more economically advantageous for the Balkan countries, China’s offer has no bureaucratic restrictions. Nonetheless, taking out China-sourced loans leads to ever-increasing state budget deficit towards Beijing. Montenegro’s deficit is estimated at 80 percent, North Macedonian – 20 percent, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s – 14 percent while Serbian – 12[20] percent. This situation has affected both some EU Member States as well as Western Balkan candidate countries. China’s infrastructure investments focus on implementing Beijing’s projects to link Asia and Western Europe, with the Western Balkan region serving as an economic foothold for China. Beijing’s strategy towards the Western Balkans is based on cooperation with state entities. The most substantial infrastructure investment is constructing a high-speed railway between Budapest and Belgrade. In May 2017, Serbia’s government received a $300 million loan from China’s Exim Bank[21]. Beijing hopes to expand infrastructure between the Greek port of Piraeus and Western Europe, treating the Western Balkans as a transit zone. A majority stake package in the port authority has been purchased by China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO). Besides, Beijing plans to expand highway connections in North Macedonia and Montenegro. The Chinese undertakings in the Western Balkans do not deem as a critical element of public debate; hence, consequences of the region’s dependence so far have not emerged as a concern for state administration.

ENERGY INDUSTRY

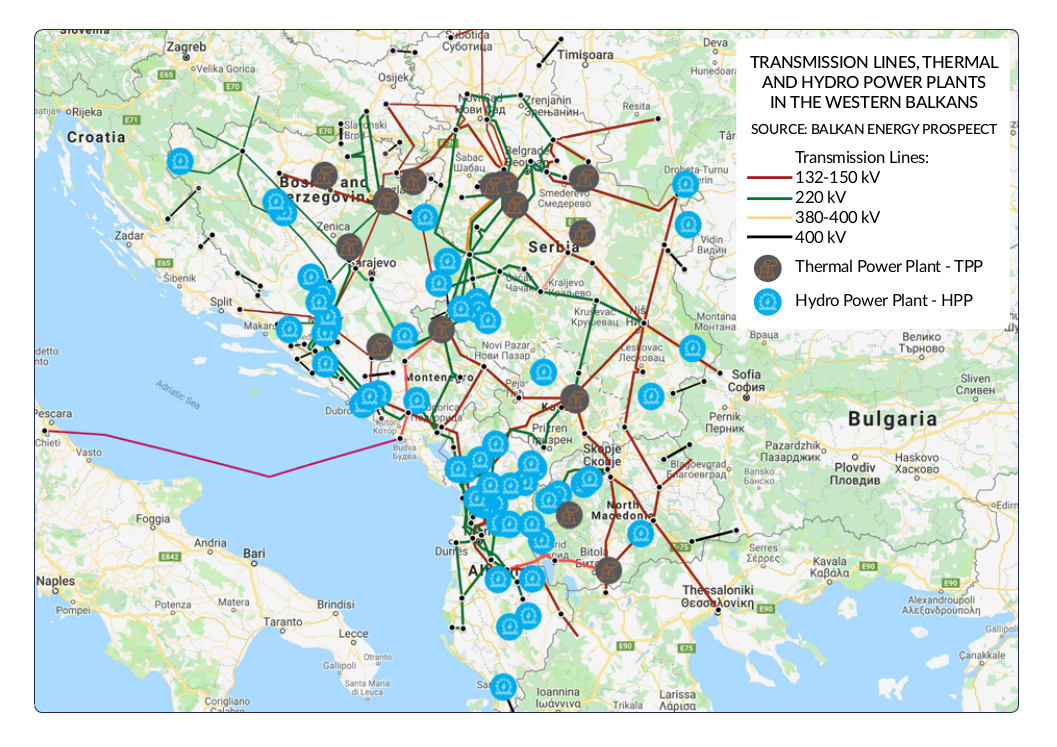

The Western Balkan countries differ in terms of their energy independence and sources. Most of them rely on Russian-sourced oil and gas, except for Albania that boasts of its own resources as well as Montenegro and Kosovo, both of which lack adequate gas infrastructure. Also, the Western Balkan energy sector is to a large extent characterized by the high share of coal energy and electricity generated by hydroelectric power plants. The major disparities are seen in the percentage of renewable energy, understood as all types except for hydroelectric power plants, in their respective electricity mixes. The Balkans’ demand for energy resources should lead to establishing a common energy infrastructure to ensure uninterrupted energy supplies to all the countries of the region.

The energy development of the Western Balkans has yet been perceived differently by the main actors operating in the region. While the European Union opts for renewable energy sources, China remains committed to bankrolling coal-based energy initiatives, and Russia seeks to exert pressure through its gas supplies. In 2005, the European Union established Energy Community, an international organization whose overall purpose was to integrate the Western Balkans’ electricity market and give non-EU Central and Eastern European countries access to European energy infrastructure.

The Western Balkans region is of particular significance for building new oil and gas pipelines to Europe. Also, the region is located along Russian and Turkish energy projects running to Western Europe, forcing the European Union to work jointly with transit countries to develop an appropriate legal framework.

Electric energy

As of 2018, total power generation capacity across the Western Balkans region was 17.6 GW, of which lignite capacity accounted for 48 percent, followed by hydropower (46 percent), gas (4 percent) and fuel oil (2 percent[22]). Although new forms of renewables are beginning to break through, they have still formed a negligible percentage of the total capacity.

Of all the Western Balkan countries, Albania has the lowest CO2 emissions to the atmosphere. The country generates most of its domestic energy from hydropower yet it still needs to import some of its electricity. As estimated, due to the climate change and the drying up of local rivers, the capacity of Albanian hydroelectric power plants may plummet by 15–20 percent by 2050[23]. Further hydropower projects have yet raised fears of the European Union, especially if they are implemented in close vicinity of natural reserves, such as that on the Vjosa River[24]. Albania already has a hydrocarbon-powered 98 MW oil and gas power plant at Vlora. Apart from its hydropower energy projects, the country is not committed to developing other renewables, including solar systems and wind farms.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s domestic energy sector relies on lignite supplies from five mines located near the power plants of Tuzla (715 MW), Kakanj (466 MW), Gacko (300 MW), Ugljevik (300 MW) and Stanari (300 MW), the last of which became operational in 2016. China-sourced loans will soon contribute to constructing Bosnia’s five more power utilities, also in Tuzla and Banovići, bankrolled by the China Exim Bank and the Industrial Bank respectively. In March 2019, Bosnia’s federal parliament has approved a guarantee for a loan from Beijing to build the Tuzla coal-fired power plant[25]. By 2016, brand-new solar energy systems had been installed in Bosnia and Herzegovina while the country’s first wind farm– the 50.6 MW Mesihovina facility in Herzegovina, financed by Germany’s KfW– started operating in March 2018[26].

Montenegro’s electricity needs are mainly met by the 225 MW lignite power plants at Pljevlja and the 307 MW Perucica and 342 MW Piva hydropower plants. Also, Montenegro announced the plan to build power utilities on Komarnica and Morača rivers. Yet the European Union has objected to Montenegro’s ambitions, hoping to cover both regions with the Natura 2000 program. A potential solution will provide for building new wind farms or solar systems to meet Montenegro’s electricity needs. Approximately 40 percent of all energy is consumed by the aluminum plant KAP, which raises criticism among local residents who needs to grapple with temporary power cuts. Another problem is Montenegro’s heavy dependence on hydropower, as a result of which the country’s local energy industry is unable to meet demand domestically during dry periods[27].

Kosovo’s electricity generation is to a great extent dependent on two lignite power stations of Kosova A (five units with 800 MW installed) and Kosova B (two units with 678 MW installed). Unlike in other countries, only 2 percent of the country’s electricity is supplied by hydropower utilities. Other renewables come from the use of wood for space heating, with district heating accounting for only 3–5 percent. In Kosovo, there is just one small wind farm with a capacity of 1.35 MW. In consequence, the country is the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases of all Western Balkan countries.

North Macedonia’s domestic electricity sector relies on coal and hydropower utilities. Its overall electric power generation capacity comes from two thermal power plants with a total of 800 MW installed capacity, eight large and several small hydropower plants with 650 MW capacity. North Macedonia has two open cast lignite mines in Oslomej and Suvodol whose annual capacity is estimated at 7 million tons and with deposits for the next fifteen years. The country remains largely dependent on electricity imports, which has risen to 34 percent of its total energy consumption, as domestic production of electricity has in recent years slumped by about 25 percent. Coal supplies are processed by the three Bitola power plant units. From 2025 onwards, domestic coal supplies will account for 50 percent of the country’s total electricity consumption. Adopted back in 2017, North Macedonia’s National Renewable Energy Action Plan stipulated that 24 percent of electricity would come from renewable sources by 2020. Also, North Macedonia has a 36.8 MW wind farm in the town of Bogdanci[28].

Like in other Western Balkan states, Serbian energy security relies on coal-sourced electricity, accounting for 70 percent of its total energy output, and the remaining 30 percent is generated in hydropower plants. Serbia’s electricity demand is satisfied with domestic production. The country’s coal reserves amount to 4.5 billion tons. Approximately 50 percent of Serbia’s electricity comes from the Nikola Tesla and Morava power plants, both of which consume annually about 30 million tons of coal. Though Serbia has undertaken commitments to develop its renewables that would account for 27 percent of total electricity output by 2020, the country so far has failed to meet its obligations. No plan to build a large hydropower utility has yet been submitted while most of such facilities would be sited in protected areas. Like in neighboring Kosovo, Serbia’s remaining renewables are limited to using wood for space heating.

On May 21, 2019 the Energy Community Secretariat released the Electricity Monitoring Report for the Westerns Balkans[29]. The document reflects some positive developments of the WB6 and identifies the pace of reforms that should be undertaken by the WB6, such as establishing a harmonized legal framework in compliance with the Third Energy Package and the power exchange. The WB6 Electricity Monitoring Report outlines some positive steps taken to form day-ahead markets in Montenegro and North Macedonia. The SEEPEX[30] (SEE Power Exchange) Day-Ahead market has emerged as a major step for creating a regional power trading solution for Southeast Europe (SEE) and has been highly anticipated by the electricity market community. The report highlights the tangible progress achieved towards the trading on the Serbian day-ahead market, which went up by 174 percent in 2018. Milos Mladenovic, Managing Director of SEEPEX[31] said that “the smooth launch of the Serbian Day-Ahead market is a cherry on the top of the liberalized power market in Serbia,” arguing that “at the same time, this is an important signal for the electricity market in SEE as SEEPEX is the first organized market place in the region that provides a high level standard both in terms of trading and clearing infrastructures.”

Speaking of the latest developments on the electricity market, the report highlights the fact that Montenegrin electricity power exchange in Montenegro is foreseen to go-live in the first quarter of 2020, meanwhile North Macedonia has made some progress as for setting the electricity market operator, which is crucial when it comes to its day-ahead market. Also, some notable achievements mentioned in the report consist in establishing the power exchange (APEX) in Albania, finalizing procedures for selecting a universal and last-resort supplier in North Macedonia – recently launched in Montenegro – and certifying transmission system operators in Kosovo and North Macedonia. However, the paper stresses out that Bosnia and Herzegovina remains the only Western Balkan state that has not yet initiated the certification procedure, which occurred due to the lack of a harmonized legal framework in compliance with the Third Energy Package.

Natural gas

As of 2017, the Western Balkan region consumed annually over 3 billion cubic meters of natural gas[32]. Though the market is referred to as relatively small, plans to gasify the region may bring a considerable increase in gas consumption. As for now[33][34], neither Montenegro nor Kosovo has natural gas sources. Moreover, both countries do not dispose of transport infrastructure or are not involved in trade exchange with their foreign partners. In 2017, Albania’s total natural gas output amounted to 50.97 million cubic meters. Also, the country neither exports nor imports any extra supplies. Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia have no natural gas sources, which forces them to import Russian-sourced raw material. Serbia’s gas resources are small, making the country import most of supplies. Russia is the chief gas supplier to the Western Balkan region, holding a majority of all gas shares to the market. Russia exports 226.5 million cubic meters of gas to Bosnia and Herzegovina per year (through the Beregovo–Horgos–Zvornik gas pipeline), 136 million cubic meters to North Macedonia (via the Dupnitsa–Skopje gas pipeline) and 2 billion cubic meters to Serbia (via Hungary and Ukraine). Serbia is making its best efforts to diversify its energy supplies thanks to building a new gas connection with Bulgaria. The Serbian-Bulgarian route, whose project was conceived in 2018, will allow for the transfer of between 1 and 1.8 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually from Bulgaria to Serbia and 0.15 billion cubic meters from Serbia to Bulgaria. Once completed, the Trans–Balkan interconnected will also become part of a significant energy initiative aimed at connecting Southeastern European countries[35].

The Western Balkans are part of significant trans-European gas infrastructure projects. Among them is the Trans Atlantic Pipeline (TAP) that is soon expected to bring gas from Azerbaijan and cross Turkey, Greece and the Adriatic Sea before arriving in Albania and Italy. The pipeline is scheduled to be completed in late 2019 and early 2020. The Trans Atlantic Pipeline is more than 80 percent completed[36]. The initial capacity of the pipeline will be 10 billion cubic meters, of which 8 billion meters of gas were contracted by Italy and 2 billion cubic meters – by Bulgaria. The Trans Atlantic Pipeline will then be extended further to the Western Balkans as the IAP (Ionian Adriatic Pipeline) project and could supply gas to the region’s states after increasing TAP’s capacity. The Ionian Adriatic Pipeline could be used to ship up to 5 billion cubic meters of Caspian-sourced gas to Montenegro Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia.

Russia has been committed to launching its gas pipeline projects in the Western Balkans independently of the European Union’s activities. Having withdrawn from the South Stream project in 2014, Moscow entered into cooperation with Turkey. Initially, the gas pipeline served as a European project yet Russia eventually refused to unbundle into separately owned energy-producing and energy-transporting companies. In consequence, Moscow made efforts to revive the project in the form of TurkStream, a pipeline running through European Turkey to Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary. On a Serbian branch of the pipeline, Russia’s Gazprom and Serbia’s Srbijagas jointly established Gastrans, a gas subsidiary company with Gazprom holding majority stakes in the newly created firm. As planned, Gastrans would be tasked with building a pipeline while Gazprom would account for supplying gas. Serbia’s undertakings met with opposition of the European Union that claimed that the country had violated principles of EU community law.

Crude oil

As of 2016, about 8.3 million metric tons (MT), or 61 million crude oil barrels, are annually consumed in the Western Balkans. The oil demand in individual countries is as follows: Albania – about 27,000 barrels a day, Bosnia and Herzegovina – about 35,000 barrels a day, North Macedonia – about 21,000 barrels a day, Montenegro – about 7,000 barrels a day; Serbia – about 74,000 barrels a day[37]. The Western Balkan countries highly rely on oil and petroleum products imports. For instance, Albania imports 28 percent of such products, Serbia – 71 percent while other countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Montenegro) – 100 percent[38].

Albania is the largest producer of crude oil in the Western Balkans, with crude oil production of 1.06 million tons in 2016, of which 872,000 tons were exported. Albania has two refineries, Ballsh and Fier, exporting 3,250 barrels of oil per day. Bosnia and Herzegovina has no oil field yet it disposes of two refineries, Brod and Modrica Oil Refineries, both of which export 4,603 barrels a day. Montenegro and Kosovo have neither oil fields nor deposits. Although North Macedonia has no oil deposits, it boasts of one refinery (Okta Skopje Refinery) whose daily export capacity is estimated at 50,000 barrels of oil. Serbia’s daily oil output amounts to 20,560 barrels while domestic crude consumption is 76,000 barrels, exceeding the total capacity of Serbian oil utilities. Serbia’s two existing refineries are sited in Pančevo and Novi Sad.

The Western Balkan chief pipeline projects are Albanian Macedonian Bulgarian Oil Pipeline (AMBO) and Pan-European Oil Pipeline (PEOP). Proposed back in the 1990s, AMBO had not been given the green light from local politicians until 2004. It will run the Bulgarian Black Sea port of Burgas via North Macedonia to the Albanian port of Vlora. Another plan is to build the Pan-European Oil Pipeline from the Romanian port of Constanţa via Serbia and Croatia to Rijeka and from there through Slovenia to the Italian port of Trieste. Both initiatives were eventually suspended due to some geopolitical tensions and the lack of financial support, also from the United States, though Washington had initially declared its willingness to bankroll energy projects aimed at making the Western Balkans independent of Russian-sourced oil.

GEOPOLITICS

The two above parts of the following report, devoted to infrastructure and energy issues, made an attempt to discuss the main challenges of the Western Balkan region. To ensure proper economic development, the countries of the region require appropriate foreign investments that will provide for their growth and will consolidate the area around shared energy and communications infrastructure. Nonetheless, some international entities promote distinct solutions for regional development. While analyzing their involvement in the Western Balkans, one could blatantly state that the central axis of the political dispute over the region’s integration runs between the European Union and NATO on the other hand while Russia on the other. As non-member states of both the EU and the North Atlantic Alliance, the Western Balkan countries remain “an arena for struggle” among these two giant political blocs. For their part, China and Turkey are outside the main axis of the conflict. Beijing has made efforts to gain a foothold in Europe in a bid to encourage its economic expansion while Ankara, which also hopes to facilitate economic development, pushes for restoring its former influence in the region. Both Turkey and China may find further EU integration endeavors as unfavorable, mainly due to legal and administrative regulations that could halt some forms of investments, seen as advantageous by the two countries.

Foreign actors and their involvement

By developing further integration programs, the European Union is making constant attempts to incorporate the Western Balkan region both into the common European market and the EU structures, all the more so that the region emerges as a European enclave that shares borders only with the EU Member States. This path of development might, however, trigger off reforms that will be in line with European principles, which causes difficulties and discourages Balkan political elites from making further efforts for EU integration processes. Facing the slowdown in EU integration, Brussels has put forward new elements, including those within the framework of the Berlin Process as an initiative for facilitating cooperation in some sectors. In particular, attention should be drawn to promoting EU-financed infrastructure and energy projects as part of the said undertaking. Brussels has taken recent actions for fear of losing influence in the Western Balkans to Russia, China, or Turkey. Pushing the EU’s political support out of the region could be detrimental to the entire community. The Western Balkans are by no means peripheral towards the European Union, and all the ethnic tensions, the increase in organized crime or the migrant influx will directly translate into the EU’s political situation.

The Russian Federation, for its part, has viewed a different vision of the region, hoping to make the Western Balkans its “stronghold” in Europe. Moscow primarily focused on targeting such activities in Serbia, referred to as Russia’s closest ally and the region’s most influential state, both politically and economically. Leaving the Western Balkans outside the European Union will give Moscow an additional opportunity to pursue its geopolitical goals in the region, enabling Russia to safeguard its monopoly on oil and gas exports. Also, Russia’s bid to sustain its influence in the Western Balkans also results from its location as a transit spot for the EU Member States.

China has eyed the Western Balkans as a “gateway to Europe.” The Western Balkan market has attracted Chinese investors as it requires ongoing foreign capital inflow and is eager to take out external loans, though increasing its debt towards China and becoming vulnerable to Beijing’s economy. Through its “16 + 1” strategy, China remains a rival economic factor as the country is actively committed to making impact investments in the region. The region’s fundamental importance for China is closely linked to the country’s commercial expansion, with the Western Balkans serving as a European logistics foothold for its investments. Building infrastructure in the Balkans will open up an opportunity for China to swiftly transport goods from the Greek port of Piraeus to Western Europe. As it seems, China has no aspiration to make the region politically depend, which is the case of Russia. Although the Western Balkans remain outside the European Union, they share EU values and standards, which creates a favorable opportunity for China as the jurisdiction of EU courts, also regarding antimonopoly issues, does not come into full effect in non-EU states.

Also, Turkey seems not to promote any particular political interest in the region, though Ankara may emerge as a dominant player if to take into account the 500-year long heritage of the Ottoman Empire and the country’s contemporary economic expansion in the region. Like China, Turkey has primarily focused on tightening business ties with the Western Balkan states. Having drifted away from the idea of EU integration, Ankara has pushed for becoming an independent regional power while, due to some historical preconditions, the Balkans seem a natural place for developing Turkey’s interests. For its part, Turkey, as a strongly growing regional power, holds interest in making investments in the Western Balkan countries.

Another part of the geopolitical game around the Western Balkans is the United States, along with its broader context of the North Atlantic Alliance. The Dayton peace accords were viewed as Washington’s political success, giving the United States a possibility to guarantee peace in the region. The U.S. primary goal consists in integrating the area with the North Atlantic Alliance while stabilizing the Western Balkans in the context of U.S.-held military operations in the Middle East and making the region as a stable foothold for the American activity. The Balkans’ integration into NATO has yet been proceeding differently and has already been achieved by Albania and Montenegro.

Geopolitics and economic projects

Infrastructure projects are in no small extent implemented by the European Union and China. Brussels has made efforts to develop significant transport routes running north to south to facilitate trade with other European regions and to expand outlets for EU-sourced goods and services. China has been committed to putting into action its infrastructure initiatives, all of which are subordinated to the country’s global interests, to ensure connections with Western Europe under the New Silk Road initiative. For China, the Western Balkans serve as a logistics base, allowing to reduce trade costs in Europe. Even having not pushed forward its ideology in the Western Balkans, China can afford to nurture an even development of its influences in both Serbia and Albania. In the short term, China’s economic expansion could bring benefits for the countries of the region, as Beijing-offered loans do not require any additional legal or environmental conditions. Growing debts towards China will make the Western Balkan states economically dependent while paving the way for Chinese companies to push out local enterprises from the market, mainly due to little price competitiveness of the latter. Both Turkey and Russia have also engaged in Western Balkan infrastructure projects, yet their participation rests on an ad hoc basis and does not intend to follow a purposeful plan to expand a given transport route. Nonetheless, Ankara, while undertaking infrastructure initiatives, focuses on their regional dimensions, and Moscow seems more committed to using its hydrocarbon sources as part of a geopolitical game.

Energy rivalry between individual actors consists of several elements, in any case. Being the critical hydrocarbon supplier, Russia seems most interested in building oil and gas pipelines running through the Western Balkans. Turkey also engages in several energy initiatives as it remains both a transit country for projects alternative to Russian ones and a keen supporter of Moscow-sourced undertakings, including the TurkStream natural gas pipeline. Thanks to cooperation with the Western Balkan states, the European Union remains committed to creating its energy security zone that will involve expanding oil and gas pipelines running through Turkey and building local connections linking the countries of the region to boost regional trade in raw materials. As for energy issues, China has made efforts to carve out a market niche for sectors that so far had not been secured by other countries; for example, Beijing has given a loan to expand a coal mine in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Main destabilizing factors in the region

The region’s main geopolitical challenge is the attitude of Albania towards its nationals inhabiting Montenegro, Kosovo, and Macedonia. Adopting a Greater Albania plan to unite all lands inhabited by ethnic Albanians has emerged as the critical challenge to bring together these territories. Also, another vital threat to the stability of the Western Balkan region is the matter of Kosovo’s independence, unrecognized by Serbia. Kosovo’s sovereignty has also emerged as a sticking point in relations between the United States and the European Union on the one hand – as most of the EU Member States accepted its declaration of independence – and Russia on the other. To make matters worse, Moscow offers reliable support for Serbia and a group of right-wing and anti-Albanian political parties in Montenegro, Macedonia and Bosnia’s Republika Srpska. On the other side of the barricade stand Washington’s bids to form alliances with Albania and Kosovo as well as to develop further cooperation with Montenegro, as the Alliance’s youngest member, within the framework of NATO and North Macedonia that intends to join the pact.

Russia’s concerns over losing influence in the Western Balkan region are chiefly linked to NATO’s activity as Montenegro’s recent accession triggered off Moscow’s sharp reaction. In October 2016, an attempt was made to overthrow the Montenegrin government in a bid to obstruct the country’s NATO ambitions. Among the convicted of staging the coup were both Russian and Serbian citizens. A part of Montenegrin society, along with pro-Serbian organizations, opposed to Montenegro’s NATO pursuits, yet such large-scale measures, which had been primarily aimed at weakening the state’s constitutional authorities, were part of Russia-led hybrid warfare activities. Russian activities in Bosnia and Herzegovina materialize through Moscow’s support for Republika Srpska in the latter’s ambitions to gain independence from the state authorities. Also, Russia is declaring support for the bodies of Republika Srpska and its leaders, thus hindering integration processes of both Bosnian statelets and that between Sarajevo and the EU and NATO structures.

Like Montenegro, North Macedonia has also grappled with Russia’s activities targeted against its accession to the North Atlantic Alliance. Most importantly, Greece blocked Macedonian membership due to the naming dispute. Greece protested that the name Macedonia, which is the same as that of Greece’s northern province, is part of the state’s cultural heritage. Under the name-changing referendum in Macedonia, Athens and Skopje eventually reached a fair compromise as the former agreed to recognize adding “North” to its official name. Russian activities in the context of the Greek-Macedonian dispute focused on the Macedonian nationalist milieu whose members spoke against the compromise deal with Athens, leading to obstructing Skopje joining NATO.

Though EU-oriented, Serbia remains a Russian foothold in the region. Close political and military ties between Moscow and Belgrade are manifested through joint military drills or establishing economic partnership on preferential terms for the Serbs. Moscow is escalating disputes between Serbia, its neighbors and the West, aware of the fact that Belgrade’s accession to the European Union will be equivalent to losing Moscow’s sphere of influence in the Western Balkans.

Importance of the European integration of the Western Balkans

Over the past centuries, the Western Balkan region eyed growing conflict. In the 1990s, the demise of the Eastern Bloc had a peaceful character in Central European countries, making it possible for them to accede to the EU and NATO. The wars of the 1990s, which raged on Balkan soil, triggered many delays in undertaking reforms aimed at modernizing the region.

The EU integration of the Western Balkans opens up their opportunity to upgrade their infrastructure and energy sector as well as to strengthen administrative structures. Also, opting for EU integration is a solution to solidifying the Balkans’ position worldwide. Without EU institutional support, the Western Balkan countries have a weaker negotiating position while carrying out negotiations with China, Turkey, or Russia. Although some states of the region are holding accession talks with the European Union, they are all at different stages, and regional initiatives are of key importance in the EU integration process.

Also, the European Union launches initiatives for facilitating the Western Balkan states’ accession due to their strategic location within the community, as after Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, the region has no land border with external countries. This may lead to tensions between the Western Balkans and the European Union in the context of Chinese, Russian, or Turkish domination. If the region rose as China’s logistic foothold, Beijing’s economic pressure on exporting goods could bring about some problems for the European Union. While carrying out hybrid warfare activities in the Western Balkans, Moscow arouses anxiety among all areas of particular vulnerability to ethnic conflicts (Kosovo or Bosnia’s Republika Srpska) or provokes an increase in nationalistic moods in North Macedonia and Montenegro. The only solution to diminishing all the negative phenomena is admitting the Western Balkan states to the European Union, followed by implementing EU-based principles.

Although we have witnessed certain positive steps towards the region’s EU accession – like the signing of the Prespa Agreement – the Western Balkans countries are still facing several challenges on their path towards the EU accession. Regional cooperation, friendly ties with neighboring countries, rule of law, fundamental rights, good governance and addressing economic reforms remain the most pressing issues for the EU enlargement, needed to sustain the “credible enlargement perspective” with regard to the new enlargement strategy for the Western Balkans on “A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans”, adopted by the European Commission on February 6, 2018.

CONCLUSIONS

Located in a strategic European region, at the crossing of trade routes from West to East and from South to North, Western Balkans are an essential place for investments. Time delays in building road, rail, maritime, and aviation infrastructure pose a challenge for the integration of Western Balkans countries. The greatest challenge consists in selecting the best path of development and in balancing infrastructure spendings, especially in the regional dimension. Further development of the Western Balkan region is to a large extent stimulated by the European Union and China while Turkish and Russian undertakings are narrowed down to some regional areas and do not offer either comprehensive solutions or significant financial capital compared to what has already been proposed by Brussels or Beijing. The biggest threat is, however, to become reliant on Chinese loans as the Middle Kingdom has consequently pursued its economic interests on European soil. To meet the region’s all needs, the European Union must yet pursue an increasingly dynamic investment policy.

Building infrastructure and setting energy links between all the states will assume both economic and political significance. Politically, one could refer to the origins of the European Union, which was to ensure that no further armed conflicts would break out through internationalized coal and steel trade. The Western Balkans, politically divided and still remembering the wars of the 1990s, may, both through the EU and regional integration processes, set up political and economic framework for stabilizing the situation in the region and contributing to its rapid development.

Authors:

Jakub Lachert – Expert, Warsaw Institute

Krzysztof Kamiński – President, Warsaw Institute

[1] Air Traffic Report 2018, http://www.tirana-airport.com/media/15496402446874TrafficReport2018.pdf

[2] Banja Luka Airport: Busy like never before, https://balkaneu.com/banja-luka-airport-busy-like-never-before/

[3] Sarajevo Airport welcomes millionth passenger, https://www.exyuaviation.com/2018/12/sarajevo-airport-welcomes-millionth.html

[4] Number of passengers at Nikola Tesla Airport increases – Net profit in first 11 months grows by 2%, https://www.ekapija.com/en/news/2328308/number-of-passengers-at-nikola-tesla-airport-increases-net-profit-in-first

[5] Nis airport statistics, https://nis-airport.com/en/traffic-figures/

[6] Pristina International Airport, http://www.airportpristina.com/news/news-15

[7] Skopje Airport aims for two million passengers, https://www.exyuaviation.com/2017/08/skopje-airport-aims-for-two-million.html

[8] Montenegro Railway, https://www.visit-montenegro.com/transport/transportation-railway/

[9] Upgrading Kosovo’s only international rail link, https://www.ebrd.com/cs/Satellite?c=Content&cid=1395278446351&pagename=EBRD%2FContent%2FContentLayout

[10] Rail lines (total route-km), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.RRS.TOTL.KM?view=chart

[11] Serbia to invest 440 million Euros in railway infrastructure, https://www.railtech.com/policy/2018/10/23/serbia-to-invest-500-million-dollars-in-railway-infrastructure/?gdpr=accept

[12]Road Safety Management Road Report, http://www.seetoint.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2018/01/10RSWG-Road-Safety-Management-Road-Authority-in-Albania.pdf

[13] Bosnia and Herzegovina: the road to Europe Transport Sector Review – Main Report, http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:fptLtLb5hh8J:documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/326351468201303951/544060ESW0v10P0ain0Report0May02010.docx+&cd=5&hl=pl&ct=clnk&gl=pl

[14]Road Traffic Safety in Montenegro, http://trans-motauto.com/sobnik/2014/3/10.ROAD%20TRAFFIC%20SAFETY%20PERFOMANCE%20IN%20MONTENEGRO.pdf

[15] Macedonia roads, https://travel2macedonia.com.mk/getting-in-macedonia/roads

[16] Upgrading Kosovo’s only international rail link, https://www.ebrd.com/cs/Satellite?c=Content&cid=1395278446351&pagename=EBRD%2FContent%2FContentLayout

[17] Serbia – Infrastructure, https://www.export.gov/article?id=Serbia-Infrastructure

[18] https://www.wbif.eu/sectors/transport

[19] Connectivity Agenda Co-financing of Investment Projects in the Western Balkans 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/connectivity-agenda-2018-sofia-summit.pdf

[20] Chinese investment could become a challenge for the Western Balkans, https://www.theglobalist.com/balkans-china-fdi-belt-and-road-eu/

[21] China lends $ 300 million to Serbia for railway overhaul project, https://seenews.com/news/china-lends-300-mln-to-serbia-for-railway-overhaul-project-568841

[22] Western Balkans power sector future scenarios and the EBRD, https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Western-Balkans-power-sector-future-scenarios-and-the-EBRD.pdf

[23] Vjosa Musliu, Third Actors in the Balkans and Energy Security, Center for Excellence Ministry of Foreign Affairs Albania

[24]European Parliament warns Balkan countries to stop destructive hydropower, https://bankwatch.org/blog/european-parliament-warns-balkan-countries-to-stop-destructive-hydropower

[25] Bosnia’s China-Funded Power Plant Gets Green Light, https://balkaninsight.com/2019/03/07/bosnias-china-funded-power-plant-gets-green-light/

[26] The energy sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina, https://bankwatch.org/beyond-coal/the-energy-sector-in-bosnia-and-herzegovina

[27] The energy sector in Montenegro, https://bankwatch.org/beyond-coal/the-energy-sector-in-montenegro

[28] The energy sector in Macedonia, https://bankwatch.org/beyond-coal/the-energy-sector-in-macedonia

[29] https://www.energy-community.org/news/Energy-Community-News/2019/05/21.html

[30] http://seepex-spot.rs/en/press/seepex-successfully-launches-serbian-day-ahead-market

[31] http://seepex-spot.rs/en/press/seepex-successfully-launches-serbian-day-ahead-market

[32] US Energy Information Administration, INTERNATIONAL ENERGY STATISTICS 2017

[33] https://www.indexmundi.com/g/g.aspx?c=mj&v=137

[34] https://www.indexmundi.com/g/g.aspx?c=kv&v=137

[35] EU investment in the gas interconnection between Bulgaria and Serbia, https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/eu-investment-gas-interconnection-between-bulgaria-and-serbia-enhance-energy -security-region-in 2018-may-17_en

[36] Trans Adriatic Pipeline, https://www.tap-ag.com/

[37] US Energy Information Administration, INTERNATIONAL ENERGY STATISTICS 2016

[38] Oil imports dependency 2016, Oil and petroleum products – a statistical overview by EUROSTAT

_________________________________

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.