SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 21 February 2019

U.S. Foothold – Russian stance towards crisis in Venezuela

- There are two reasons why Venezuela’s controversial leader is not yet fighting a losing battle against the country’s opposition. First, Venezuela’s military has pledged its loyalty to the leader since the beginning of the crisis while other military branches declared to stand by the president. Secondly, the government in Caracas is in the hopes for getting support from the world’s top players–with Russia at the forefront–because Moscow’s assistance is essential to back the country’s armed forces.

- The Kremlin is doing its utmost to prevent Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s administration from collapsing, which is because of Moscow’s desire to extend its zone of influence in the western hemisphere. If the regime falls, making Caracas reorient towards pro-American policy, Russia along with its allies will be doomed to bear great losses in Latin America. This was also due to the fact that Russia has heavily invested in the Venezuelan regime, for instance by securing stakes in the local oil sector.

- However, the dramatically worsening economic situation in Venezuela increases the risk of Russian investments and loans in the local oil sector. Russian state-run giant Rosneft has granted credits worth a total of 6.5 billion dollars for Venezuela’s PDVSA oil firm, out of which the latter so far managed to pay off 3.4 billion dollars, mostly by shipping oil supplies. Moreover, PDVSA’s assets were in the pinnacle of Western creditors. Such an absolute breakdown of the Venezuelan economy, prompted by political transitions in Caracas, may even end up with losing billions of dollars invested by the Russians.

- Venezuela’s domestic conflict constitutes for the Kremlin yet another area for rivalry against the United States. Russian officials have accused Washington of making several attempts to trigger a “colorful revolution”, a move that would ultimately make Venezuela America’s regional vassal. Facing such a situation, Russia is likely to take some steps that can be referred to as little rational, especially if compared to Beijing’s pragmatic approach.

- Moscow provides Maduro’s regime with essential support via both diplomatic and informal channels, the latter of which seems best evidenced by facilitating all activities related to military counseling and trading gold reserves. If the fall of Maduro’s rule was just a foregone conclusion, the main goal is to prolong the regime’s agony while fuelling the political turmoil in Venezuela, all of which would ultimately lead to a destruction of the national oil sector. Further, it would be profitable to make its recovery process and export restoration last as long as possible.

SOURCE: kremlin.ru

SOURCE: kremlin.ru

Facing the Crisis

Russia, which has provided Venezuela with a dozen of loans and investments worth a total of several billion dollars over the past twelve years, recently expressed its strong backing for Nicolas Maduro. The day after Juan Guaido’s declaration to seize power in the country on January 23, the Kremlin and Russian Foreign Ministry confirmed that Russia continued to recognize Nicolas Maduro as the legitimate leader of the country, warning “third countries” against possible interference from outside. In its statement, Russian Foreign Ministry specifically pointed out who can be referred to as “third countries”, which was in line to Moscow’s strategy of considering Venezuela as a new area for the U.S. rivalry. “We see in the unceremonious actions of Washington a new demonstration of total disregard for the norms and principles of international law, an attempt to play the role of the self-proclaimed arbiter of the destinies of other nations,” the statement reads. On the same day, Vladimir Putin held a twenty-minute telephone call with his Venezuelan counterpart. On January 24, 2019, the Kremlin noted that the Russian President voiced support for the legitimate authorities of Venezuela. In the light of a narrative presented later to the public, Putin purportedly said that the conflict has been “inspired by external factors” while such an “interference” can be referred to a serious breach of international law regulations. A sharper response came from a spokeswoman for Russian Foreign Ministry Maria Zakharova stating that “events in Venezuela showed how the West is in manual mode change the government in other countries.” Distinct attention should be drawn to the plural form as the Kremlin had clearly predicted further steps made by the EU countries.

Initially, Moscow had no intention to make unambiguous support for Maduro’s regime look like an action far going beyond both diplomatic and political level. On January 25, 2019, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that Venezuelan leader did not request assistance in connection with the political crisis in the country. Earlier that day, Alexander Shchetinin, head of the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Latin America department, stated that Moscow offers to mediate between the Venezuelan government and opposition amid a political crisis if such efforts are required. Interestingly, the content of his announcement was somehow contradictory as illustrated by a claim that Russia has not contacted the interim president Juan Guaido and, more importantly, has no intention to do so. Russian Foreign Minister and Shchetinin’s superior, Sergey Lavrov, announced that Russia will firmly protest against the U.S. “hostile” policy towards Caracas during the next United Nation Security Council meeting, scheduled to take place in Venezuela the following day. Moscow’s reaction to the political turmoil in its South American ally that came only a few dozen hours after Guaido’s breakthrough speech may hinge on the three major beliefs. First, Venezuela’s only legitimate government is the one that pledges loyalty to Nicolas Maduro and only such authorities deserve to receive Russia’s full support. Secondly, the dispute needs to be settled with all peaceful means available, without any foreign interference. Thirdly, the U.S.-led coalition of “third countries” acts against the two first premises, thus violating principles of international law.

The first U.S.-Russian clash occurred during the UN Security Council meeting held on January 26. Russia, China, South Africa and Equatorial Guinea blocked a U.S. push for a U.N. Security Council statement expressing full support for Venezuela’s National Assembly as the country’s “only democratically elected institution.” Nonetheless, this cannot be described as Moscow’s total success as it failed to prevent an extraordinary U.N. Council meeting from being convened. Only four out of fifteen permanent and non-permanent members backed Nicolas Maduro while two countries abstained. Nine countries voted in favor of the meeting, which prompted the U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to fiercely accuse them of “either standing with the forces of freedom, or being in league with Maduro and his mayhem.”

source: kremlin.ru

source: kremlin.ruNonetheless, the Russian message was most troubled by potential mediation. Venezuelan ambassador to Moscow Carlos Rafael Faria Tortosa was first to announce his country’s readiness to accept Russia’s arbitration in order to set a dialogue between the government and the opposition. On January 28, 2019, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov reiterated the position adopted by Russian Foreign Ministry a few days before, claiming that Russia did not contact Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaido, who declared himself the interim president of Venezuela and had no plans to do so. Bearing in mind such categorical reluctance and refusal of one of the parties to the conflict to hold talks, all attempts to mediate are already doomed to fail. U.S. further steps forced Russia to toughen its hitherto attitude. On January 29, the Trump administration informed about new sanctions to be imposed against PDVSA, Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, and the country’s primary source of income. Not only did they hit financial aid for Maduro’s regime but newly adopted restrictions also posed a serious threat to Russia’s interests in Venezuela, including those of Rosneft that conducts a number of joint oil projects with its Venezuelan peer. It is noteworthy that the latter owes Sechin’s company a total of 3 billion dollars. In the light of such circumstances, Moscow’s fierce reaction is not surprising, prompting the country’s conflict with the United States. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said on January 29 that U.S. sanctions are equivalent to an attempt of blatant and illegal interference in Venezuela’s domestic affairs. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that U.S. sanctions against PDVSA are illegal, by the means of which the United States intends to confiscate Venezuela’s state assets. “Russia will take all necessary steps to support the administration of President Nicolas Maduro”, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was quoted as saying.

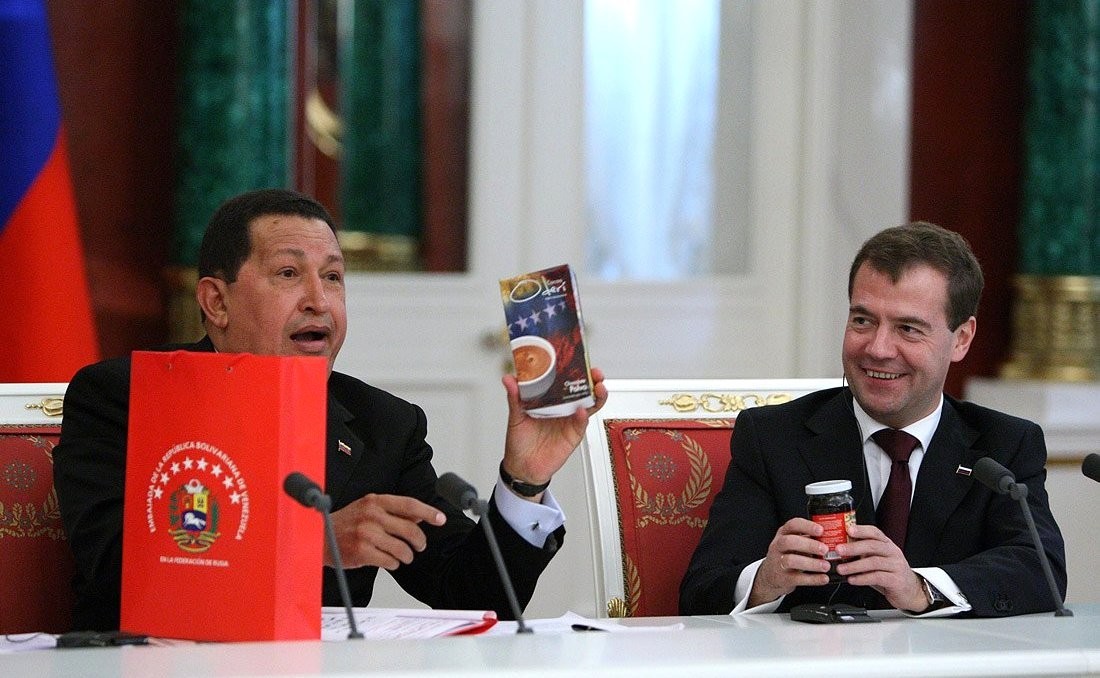

Russia’s Alliance with Chavez

Firm relations between Russia and Venezuela seem to date back to 2006 while the alliance between the two countries developed in September 2009 after Hugo Chavez’s trip to Moscow and Tehran. The late Venezuelan president followed the example of Russia and Nicaragua, recognizing Georgia’s pro-Russia separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states. His decision was reportedly influenced by Igor Sechin. Interestingly enough, Nicolas Maduro was in no hurry to acknowledge Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine. Following Chavez’s trip to Moscow, Venezuela got a $2.2 billion loan for the purchase of Russian weapons, including 100 tanks (92 Russian T-72 tanks along with 8 T-90 armoured fighting vehicles), S-300 Antey-2500 surface-to-air missile systems (equipped with radar along with ballistic missiles of a range capacity up to 400 kilometres) and the Smerch rocket launcher. Moscow committed itself to offer aid to develop Venezuela’s nuclear program while Caracas has inked deals securing investment from Russia in its oil fields.

source: kremlin.ru

source: kremlin.ruSince 2006, Russia has invested over a dozen billion dollars in Venezuela. Yet money is not the most important factor as Moscow is known for writing off debts of some Asian, African or Latin American countries in exchange for concrete political profits, as exemplified by the Kremlin’s decision to pardon Cuba’s 32-billion-dollar claim. Naturally, the Russian-Venezuelan alliance is targeted against the United States, thus aiming to attract Washington’s attention while diverting it from Russia’s activities in Central and Eastern Europe. Moscow-Caracas partnership, which seems best exemplified by a handful of symbolic gestures, including flights made by strategic bombers, seeks to demonstrate how far Russia’s influence may reach. According to the Kremlin’s strategy, Moscow has both the right and possibility to dispose of military aircraft stationed in the Caribbean Sea region, just as the United States is entitled to deploy its battalions near the border of the Baltic exclave of Kaliningrad. Venezuela constitutes a strategic link of a Bolivia-Venezuela-Nicaragua-Cuba axis that runs from the center of South America to southern U.S. borders.

On December 6, 2018, Russia’s Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu declared at a meeting with his Venezuelan counterpart that his country is interested in further employing of military aircraft and vessels from Venezuela’s airports and naval ports as part of the previously concluded bilateral agreement. Padrino Lopez said in his turn that Caracas hopes that Moscow will help modernize its military equipment. Only four days later, four Russian aircraft, including a pair of strategic Tu-160 bombers capable of carrying conventional or nuclear-tipped weapons, an An-124 Ruslan cargo plane and a long-range Il-62 jet airliner were among aircraft that landed at Maiquetia airport just outside the Venezuelan capital. The Il-62 passenger jet carried a hundred of Russian officials. This was the third time when nuclear-capable aircraft flew to Venezuela (both the previous ones had taken place in September 2008 and November 2013). The aircraft were not armed with nuclear weapons, Russian Defense Ministry stated. In a statement released on December 12, the OAS General Secretariat said that the visit violated the Venezuelan constitution, under which any foreign military missions needed to be authorized by the state’s parliament. Moscow’s decision to transfer nuclear-capable strategic bombers to Caracas was immediately criticized by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo who condemned actions undertaken jointly by Russian and Venezuelan authorities, saying they are “two corrupt governments squandering public funds, and squelching liberty and freedom while their people suffer.” A pair of Russian Tu-160 bomber aircraft took part in joint drills with the Venezuelan Air Forces that flew Russian-made Su-30 and U.S.-made F-16 fighter jets. Russian bomber aircraft traveled over the Caribbean sea during a 10-hour training session while being escorted by Venezuela fighter planes. On December 14, 2018, Russian bombers returned to their home base of Engels.

source: mil.ru

source: mil.ruRussian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced Moscow’s intention to carry out further bomber flights to Venezuela, followed by deploying naval vessels equipped with Kalibr cruise missiles. In consequence, a significant part of the U.S. territory will be located within the reach of Russian missiles. According to the Kremlin, the deployment of bombers to Venezuela was in response to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization establishing bases close to Russia’s borders. Sending Russian strategic bombers to Venezuela was supposed to alert the United States to Putin’s readiness to employ the country’s nuclear arsenal if necessary. These weapons are the only domain in which Russia may feel free to claim rights to equal treatment of Moscow and Washington. This seems particularly important in today’s context as the Trump administration is trying its utmost to withdraw from subsequent disarmament treaties with Russia. Tu-160 Blackjack bombers are capable of carrying newest Kh-101 long-range cruise missiles that have been test-fired at targets in Syria and Kh-102 with nuclear warheads. They have a range of 5,500 kilometers, meaning that a Tu-160 jet can launch nuclear missiles at the continental part of the United States almost immediately after takeoff from Venezuela.

Back in December 2018, Moscow and Caracas made an attempt to reconsider the issue of Russian military facilities on Venezuelan soil. The deployment of the Tu-160 strategic bombers to Venezuela restored an idea of setting a Russian base on the island of La Orchilla located about 200 kilometers northeast of Caracas. The Caribbean island is currently home to the Venezuelan naval base and military airport. In 2008, Hugo Chavez, who was president at the time, offered Russia the use of La Orchilla military airfield to base its long-distance strategic bombers. The island was later visited by Russian experts and air forces commanders. Nonetheless, Dmitry Medvedev, then Russian president, eventually chose to decline Chavez’s proposal. During his last trip to Moscow, President Nicolas Maduro was promised a financial aid worth a total of 6 billion dollars, a feasible price for letting Russian air forces station on Venezuelan soil.

Rosneft and loans

From 2006 to 2013 Hugo Chavez visited Russia eight times as president while his successor, Nicolas Maduro, made four trips to the Russian capital within six years. Nonetheless, it is Igor Sechin that has acted as the Kremlin’s main liaison to top Venezuelan officials since the mid-2000. Rosneft’s current CEO and former Russian Deputy Prime Minister often travels to Venezuela while Putin arrived there only in 2010 when he served as Russia’s Prime Minister. Since 2008, Rosneft’s chief has been head of the High-Level Russian-Venezuelan Intergovernmental Commission while a year later he announced establishing a Russian-Venezuelan joint consortium tasked with handling oil deposits in the Orinoco River Basin. In 2010, Chavez said that Venezuela inked an agreement with Russia for a loan of 4 billion dollars to acquire weapons. Moreover, Russian State Atomiс Energy Corporation ROSATOM ratified the deal with Venezuela concerning the construction of a nuclear power station. After Putin became Russian President in 2012, Sechin was designated Rosneft’s CEO. Speaking of Russia’s national market, the oil firm succeeded to take over such enterprises as TNK-BP and Basneft, becoming a convenient tool for the Kremlin’s international policy also in Venezuela, Cuba, Vietnam, Qatar, Egypt, and India. Sechin visits Caracas once or twice a year so it seems obvious that Rosneft is now expected to transmit Russian financial aid to its South American ally. Such a decision was not incidental, though. First, Sechin has long specialized in Latin America and other countries belonging to the Romance-speaking world. On the other hand, Rosneft’s key role can be easily explained due to Venezuela’s position in the world’s top oil giant. Nonetheless, due to his firm’s long-term commitment, Sechin seems to have much to lose. Overthrowing Maduro will trigger heavy financial losses for Russia, not to mention the failure of its economic undertakings. These are to be most experienced by Rosneft and Rosoboronexport, or two Russian business entities that remain closely linked to the state structures that implement the Kremlin’s policy worldwide. Moreover, Venezuela’s PDVSA owes the former a total of 3.1 billion dollars.

Back in 2008, Sechin introduced five of Russia’s most influential oil companies to Venezuelan market, four of which, except for Rosneft, eventually withdrew. In 2014, Rosneft made $4 billion in prepayments to PDVSA to be covered by future oil shipments. Between May 2016 and April 2017, the Russian company added further 2.5 billion dollars to the total. The funds were also transferred in advance for contracted delivery of the raw material. In a controversial report published in 2017, experts from top Russian lender Sberbank compared Sechin’s firm to an “unfortunate investor” financing an asset that is on the brink of bankruptcy. Rosneft spent a total amount of 8.5 billion dollars in Venezuela, of which over 6 billion were cash advances. In November 2017, Russia signed an agreement to restructure $3.15 billion of debt owed by Venezuela, agreeing to spread the payments out over the next 10 years. But even after the claim was written off, Venezuela partly managed to implement its obligations under the deal, according to which it should deliver no less than 380,000 barrels per days. In 2018, Rosneft, which was initially to handle the Amuay refinery (with an overall capacity of 650,000 barrels per day), withdrew from the contract due to the “terrifying conditions” in which its facilities are located. Sechin’s company received the last installment in a total amount of 500 million dollars that came in cash in the third quarter of 2018. The next payment should be reimbursed by the end of March. On January 29, Russia Deputy Finance Minister said Moscow is in the hopes for Venezuela’s payment on a Russian loan, adding that “everything now depends on the army, on the soldiers, on how true they will be to their service and oath.” Interestingly, Storchak was part of a Russian delegation that visited Caracas in autumn 2018 in order to advise on how to avoid financial collapse.

Source: pdvsa.com

Source: pdvsa.comRosneft accomplished to secure its loans to PDVSA thanks to numerous shares in Venezuela’s major oil fields. In December 2017, Sechin’s company was awarded licenses to develop the Patao and Mejillones fields in the Caribbean Sea. Speaking of Rosneft’s on-land projects, particular attention should be drawn to its partnership in numerous deposits, including those of Petromiranda, Petromonagas, Petrovictoria, Boqueron, and Petroperija, where the firm holds minority shares. In 2017, the total oil output in all ventures that involved Rosneft’s assistance amounted to 8.06 million tonnes, or 161,000 barrels per day. Russia’s contribution hit 3.14 million tonnes, or 60,000 barrels per day, which accounts for 1.3 percent of Rosneft’s total production. Once purchased in Venezuela, oil supplies are then either shipped to India – where they are sold – or sent to Rosneft’s Germany-based refineries in order to be processed. In 2016, Russia’s Rosneft signed a deal under which it acquired 49.9 percent of shares in Citgo as collateral for financing a $1.5 billion loan for PDVSA. In the light of recent events, it is almost certain that Washington will not allow the Russian company to become a formal owner of nearly half of the shares in a U.S.-registered firm that disposes of its own refineries in Venezuela.

Maduro’s demise will drag Russia’s Rosoboronexport, the main supplier of Venezuela’s Armed Forces, into economic troubles. Since 2001, this Russian top military exporter has awarded Venezuela with loans for purchasing weapons and necessary equipment. In 2013, a total worth of all business arrangements was estimated at 11 billion dollars. In 2006, Rosoboronexport had agreed to invest a sum of 474 million dollars to build in Venezuela Kalashnikov factories that would manufacture assault rifles along with munitions. Nonetheless, the project’s implementation was often suspended as the villagers were stealing materials from the construction site. According to latest plans, the country’s Kalashnikov plant was due to begin rifle production by 2018, though nothing happened. In 2017, Rosoboronexport allowed lending Venezuela 1 billion dollars to develop Caracas’s military-related programs, mostly through purchasing Russian weapons. The due date for repaying the debt was scheduled for 2027 yet the problem is that Maduro already spent the entire sum. If his administration is to be overthrown, Venezuela’s new authorities will probably have no intention to pay off these financial liabilities.

While speaking of Russia’s interests on Venezuelan soil, one must mention Gazprombank’s investments. Russia’s state-run financial institution held a 40-percent stake in Petrozamora, a joint venture established along with Venezuela’s PDVSA. The company was supposed to handle four oil fields; nonetheless, this initiative was doomed to fail as Gazprom eventually decided to pull out of the venture. In the past, such Russian corporations as KamAZ, AwtoWAZ or Rusal aimed to build their factories in Venezuela. Moscow has already helped Caracas to circumvent U.S. restrictions. At the end of his regime, both countries established a joint Evrofinance Mosnarbank as Chavez had acquired 49.9 percent of a Moscow small and little-known bank. The remaining 50.1 percent of the stakes are split between Russian state-owned banks Gazprombank and VTB Bank as well as some private entities controlled probably by Putin’s closest associates, among which ITC Consultants of Cyprus and New Financial Technologies LLC can be distinguished. Initially recognized as the major source of financing for joint oil and infrastructure projects, Evrofinance Mosnarbank was granted a local banking license in Venezuela, opened an office in Caracas and even advised on issuing bonds worth a total of over 3 billion dollars. Venezuelan officials ordered regional banks and firms to forward international transactions through Evrofinance Mosnarbank, also to exchange Venezuelan bolivars into euro, Chinese yuan and other currencies, except for U.S. dollars. The bank can hardly come as a key player in the Russian banking sector. As at September 1, 2018, its assets amounted to 57.8 billion roubles (881 million dollars) or less than 0.1 percent of all assets of the Russian banking sector.

source: kremlin.ru

source: kremlin.ruThe situation has dramatically deteriorated so it does not come as s surprise that during the Putin-Maduro meeting held on December 2018 at the Novo-Ogaryovo state residence, Venezuelan leader asked first and foremost for financial aid. Following the talks, Maduro announced that Russia had signed investment deals worth more than 6 billion dollars in Venezuela’s oil and gold sectors, accounting for 5 and 1 billion dollars respectively. Venezuelan President declared that Russia will provide a supply of 660,000 tonnes of wheat. Venezuelan leader explained that he had approved a contract which guarantees “Russian investment to raise oil production ” to almost a million barrels” per day. According to Maduro, a group of Russian experts and entrepreneurs will soon pay a visit to Venezuela in order to examine possibilities of investments in diamond mining. Back then, the Venezuelan opposition had warned that Maduro had no legitimate right to seal any financial deals. From Moscow’s point of view, another troublesome issue is that Venezuela’s authorities consider repaying their obligations to China the top priority, which is due to the fact that Beijing has invested several times more than Moscow while disposing of specific business assets over the country. The Kremlin is thus left alone with Venezuela’s various commitments on providing prepaid oil supplies, not to mention previous promises to reimburse for military equipment and production capacity of defensive facilities that were to be constructed on Venezuelan soil. This seems to explain the reasons behind Sechin’s visit to Caracas in late November 2018. It is widely known that Rosneft’s CEO sought to broach the issue of debts, intending to ask whether financial obligations under the Chinese treaties are paid on time while the Russian ones are permanently delayed.

Domino Effect?

Venezuela’s political and economic crisis seems to have become yet another front of the Cold War between Russia and western countries. According to Russia’s “party of war”, a group that currently wields power in Moscow, the situation in crisis-stricken Venezuela directly stems from the U.S. imperialist conspiracy to oust Russia’s South American ally. Russia “hawks” seems to truly believe in such a narrative, which makes them different from much more pragmatic Chinese who have heavily invested in developing their assets in Venezuela. Overthrowing the Maduro-led regime is likely to trigger a domino effect, depriving other pro-Russian governments of their hitherto power. This may happen due to both economic – as the Chavista regime caters for cheap, or even free oil, as well as military and political reasons. Venezuela is by far the largest country among all Kremlin’s Latin allies. Apart from its key strategic location, the country benefits from its enormous oil reserves and armed forces that are considered massive among other Latin American armies. For instance, the Chavez-founded regime is in close cooperation with Cuba, developing a common security partnership in such key areas as the army or special services. Furthermore, Venezuela is an important link in the Latin American drug trade, through the territory of which runs the main smuggling route for Columbian cocaine. This massive criminal activity could freely develop under the state’s shield. It involved also Russian mafia while part of the profits made is reportedly sent to subsidy such organizations as Lebanon-based Hezbollah, which resulted from the Venezuela-Iran cooperation, established back in Chavez’s times. If Moscow decided to come into contact with Juan Guaido while persuading Maduro to hold talks that resulted with a political transformation, Russia would probably be capable of saving some – or even most – contracts and money. Nonetheless, this would destroy all hopes for making Venezuela the Kremlin’s foothold in its “fight” against the United States. It seems that the Kremlin cares more about employing its military facilities located at the Caribbean coast for such purposes than about making profits worth a dozen billion dollars. The flamboyant leader of the LDRP Vladimir Zhirinovsky was the first to call on Putin to send Russian troops to prop up Maduro, stating that “if Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers fly to Venezuela and begin patrolling its skies, no one will dare to intervene.”

However, Russia is unlikely to conduct a military operation modeled on the Syrian intervention as a similar undertaking is impossible because of vast distance and Venezuela’s geographical location. From a logistics point of view, it is futile to set up a safe and permanent supply line, comparable to the famous “Syrian express”, to link Russia with Venezuela across the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. This undertaking is already doomed to fail as Moscow does not have any other regional ally that could deliver ground forces. Needless to say that Venezuela is enclosed by Brasil and Columbia, Latin American military powers, both of which are hostile to Maduro’s regime. Russia’s presence in the region would spark protests in almost all neighboring countries. Unlike in the Middle East, the United States, which is still strongly yet unofficially attached to the Monroe Doctrine, will prevent Russia from performing an armed intervention.

Russia is by no means obliged to provide military support to the Maduro-led regime. During the first days of the political crisis, Venezuela’s Armed Forces, the most powerful and popular state institution and the region’s third military power only to Brazil and Colombia, pledged loyalty to the leader. Ultimately, Maduro may feel satisfied with its neutrality, hoping that troops will stay in the barracks while other armed groups will be deployed to suppress riots. These are to include Venezuela’s elite National Guard, a military unit that consists of 23,000 servicemen, and a group of 400,000 Chavist civilian volunteers supplementing paramilitary branches of the National Bolivarian Militia of Venezuela. This reserve force, which is composed of unskilled workers that vastly benefited from Chavez’s socialist system, should not be underestimated: they had acted as one of the actors in the failed 2002 coup against Hugo Chavez. Russian military training staff has been transferred to Venezuela to train the local army. Back in time, Venezuela purchased various pieces of Russian military equipment. Under consecutive regimes, the government in Caracas concluded military deals worth a total of 11 billion dollars. Venezuelan army is mainly propped up military equipment purchased from Russia, including Buk-M2 and Antey-2500 air defense missile systems, Sukhoi Su-30MK2 fighter aircraft, Mi-35M helicopters, T-72 tanks as well as BMP-3 and BTR-80 combat and armored vehicles. Only recently has Venezuelan military branches received Russian-built Smerch rocket launchers and Msta self-propelled howitzers. Particular attention should be also drawn to a fact that Venezuelan troops used grenade launchers and anti-aircraft guns purchased from Moscow, as reported in a propaganda statement from military drills conducted on January 27, 2019.

Russian mercenaries and Venezuelan gold

While neither cruiser jets nor bombers can be deployed to Venezuela, Russia must fall back upon its “advisers”. Up to 400 Russian mercenaries could have been deployed to Venezuela, Reuters agency informed on January 18, 2019. They were to join the first contingent, reportedly sent to Caracas in May 2018. Among them are allegedly private military contractors of the Russian private military company Wagner whose main aim is to beef up the security of President Nicolas Maduro.

The story’s main source was Yevgeny Shabayev, the head of the Committee of the All-Russian Officers’ Assembly, who seeks to protect rights of mercenaries while opting for legalizing such type of activities in Russia. The Wagner Private Military Company “received an urgent order to form a group and was tasked with protecting Venezuela’s most important public figures,” he told Reuters reporters while his statement was later repeated by Russian Radio Svoboda. This was to happen before new anti-government riots sparked in Venezuela. The group comprises Russian mercenaries who previously operated in African countries, from where they flew to Venezuela. The contractors used chartered aircraft to take them to the Cuban capital Havana where they boarded commercial flights bound for Caracas where they arrived in on January 22, Shabayev said, adding that Russian mercenaries are in Venezuela to protect Maduro. Their task is to prevent rogue members of Venezuela’s security forces from detaining the president. Shabayev’s story was confirmed by Reuters’s two other sources, including reports that most of the contractors arrived at Venezuela in January and they had not flown from Russia but from various countries where they had stationed. Nonetheless, no other press agency so far confirmed that Wagner had around 400 individuals in the country as the group was purported to be much less numerous. Some sources said a small number of contractors first arrived in Caracas in advance of the disputed May 2018 presidential election, won by Nicolas Maduro. In January 2019, Russian state jets intensified their flights to Venezuela and neighboring countries. For instance, the Il-96 of Rossiya Airlines, which is in charge of transporting Russian top officials, flew from Moscow to Dakar on January 19, from where it later headed to the capital city of Paraguay and then the city of Ciudad del Este before arriving in Cuba on January 23. No flight details have been revealed as the plane’s onboard transponder was switched off above the Cuban territory.

source: kremlin.ru

source: kremlin.ruKremlin spokesman denied news reports that Russian private military contractors were in Venezuela to protect Maduro. Hosted by a Russian TV programme, Peskov responded that “fear has big eyes,” while earlier he had said that they “have no such information.” In fact, Russia has no facilities on Venezuelan soil – unlike Syria or Sudan – where such a guard would be needed. All oil projects developed by Russia’s Rosneft are headed by Venezuelan state-run firm PDVSA. Perhaps the main aim is to protect some military-related facilities. Russian state-run Rosoboronexport appeared in Venezuela some time ago, reportedly to construct its factories where Kalashnikov rifles would be assembled. Thus there may be a group of Russian armed units that were sent to the area. Speaking of Maduro’s personal protection, there is no need to deploy Russian servicemen as thousands of Cuban officers and secret agents are enough to ensure the president’s security and suppress riots in the country. It is noteworthy that Havana, Caracas’s closest ally, receives some 50,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude and fuel, helping to keep basic social standards in Cuba while Cuban intelligence operatives in Venezuela have been a crucial factor in the continued support of Maduro, thus fighting to maintain Cuba’s communist regime. Russia does not need to involve its military forces or mercenaries as Cuba, another common ally of Moscow, and Havana is much closer. Back in time, Cuban security police proposed its help to Hugo Chavez to set up an oppressive apparatus, providing Venezuelan services with some totalitarian methods that could be employed to resist the opposition.

Most of Venezuela’s gold holdings had been stored in both U.S. and European banks until 2011, accounting for 233 tonnes of the country’s total reserve of 365 tonnes. However, in August 2011, Chavez declared his intention to repatriate all gold bars from foreign-led institutions. In November 2012, only 57 tonnes of gold remained abroad, mostly in Russia. The Russian independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta reported that about 30 tonnes of gold belonging to Venezuela were stored at the Central Bank of Russia until January 2019. Their market price was valued at 1.2 billion dollars, though the head of the Central Bank of Russia Elvira Nabiullina denied such reports. Nothing is known about how many gold volumes may have been traded in January 2019 with some Russian assistance. According to sources in Novaya Gazeta, Bloomberg and Reuters, Venezuelan gold was simply exchanged for cash.

As disclosed by the media, a plane flew a route Moscow-Dubai-Caracas-Moscow twice. A Boeing 757 cargo aircraft loaded with gold traveled from Moscow to Dubai where it was eventually unloaded and handed to employees of the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates, who arrived in armored cars. Gold was unloaded while containers packed with U.S. dollars were placed onboard. The aircraft then headed to Caracas, where money was taken out before returning to Moscow. Republican U.S. Senator Marco Rubio wrote on his Twitter account that part of Venezuela’s gold reserves is purchased by the UAE-based Noor Capital investment group.

The Boeing 757 cargo plane is owned by a private company registered in Russia’s Far East city of Khabarovsk. Interestingly, it is the only aircraft that belongs to a firm solely held by a Russian citizen. On January 18-19, the jet flew a route Moscow-Dubai-Agadir (Morocco)- Caracas route before returning to Moscow on January 21-23 via Agadir and Dubai. On January 29, the plane flew out of Moscow heading to Dubai, from where it left for Venezuela, stopping by in Morocco and Cape Verde, before arriving in Caracas on January 30. On the morning of February 2, the plane landed back in Moscow, earlier making a short stopover in Casablanca.

In addition to the gold stored in Russia, Maduro will attempt to liquidate reserves kept in Venezuela’s Central Bank in Caracas. However, nothing is known about whether and how much gold was shipped to Moscow, both with the Boeing 757 and other aircraft. In late January, a Boeing 777, another private-owned plane that operates charter flights from Russia to Thailand, was sent to Caracas with no passengers onboard. Venezuela’s opposition members claimed that this was Maduro’s effort to ship 20 tonnes of gold to Moscow, from where it might have been trafficked to Dubai. The Chavista government considers selling gold an opportunity to raise funds necessary for the regime’s further functioning. Latest U.S. sanctions against Venezuela’s PDVSA, which were introduced on January 29, may cost the authorities in Caracas up to 11 billion dollars, not to mention another 7 billion dollars that remain on the U.S. bank account to which Maduro has no access. On February 1, Reuters reported about Venezuela’s plan to sell 29 tonnes of gold held in Caracas to the United Arab Emirates while 15 tonnes more will be shipped to Dubai in the coming days, all of which will be exchanged for the euro. A day later, Bloomberg wrote that the Venezuelan authorities eventually decided to suspend the deal, even if gold shipment, worth a total of 850 million dollars, was ready to be dispatched.

Conclusions

While analyzing Russia’s policy towards the crisis-stricken Venezuela and Moscow’s earlier involvement encompassing political, military and economic domains, it is certain that the Russian authorities will back the current regime until it eventually collapses. Nonetheless, if Moscow decided to support the country’s opposition, it would have a chance to save at least some of its deals yet failing to sustain military cooperation. The Kremlin seems more committed to geopolitical issues rather than financial losses. Maduro has no intention to escape and enjoys wide support from generals. Maintaining the army’s loyalty towards the Maduro-led regime is likely to become a top priority both for the Venezuelan leader and the Kremlin. It is therefore to be expected that Moscow will award financial aid to cater for the regime’s expenses. If it is not for Maduro’s victory, Russia will surely make considerable profits from Venezuela’s long-lasting crisis. Moscow’s essential intent is to destabilize the political situation in Latin America, nurtured by the still-evolving recession in Venezuela as it exerts considerable impact on the country’s neighbors, with particular regard to those being U.S. allies.

Moscow’s plan provides for maximally prolonging the agony of Maduro’s regime. Russian attempt to fuel the conflict may eventually spark a civil war in Venezuela. With some help from Cuban officers, both Russian military advisors and groups of well-trained contractors may play a leading role while backing militia branches that stay loyal to Maduro and hope to occupy the state’s largest cities, including Caracas, Valencia, Barquisimeto, Maracaibo, and San Cristóbal, or Venezuela’s top oil facilities. The longer the crisis is Venezuela lasts, the less oil is provided to the world market, causing great difficulty for the United States.

The publication of the Special Report was co-financed from the funds of the Civic Initiatives Fund Program 2018.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.