SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 26 March 2019 Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

Russia’s Hybrid Warfare in the Western Balkans

“Russia continues to seek to redraw international borders by force. And here, in the Western Balkans, Russia has worked to destabilize the region, undermine your democracies, and divide you from each other and from the rest of Europe.” – U.S. Vice President Mike Pence, Podgorica, August 1, 2017

- Russia sees further processes of NATO and EU enlargement to the Western Balkans as a potential threat, hoping to keep the region away from these Western structures.

- Russia destabilizes the region by sustaining “frozen conflicts” and escalating tensions, which is nourished by economic policy, propaganda and disinformation tools while using pro-Russian milieus to perform subversive activities.

- Moscow will thus strive to undermine peaceful agreements reached back in the 1990s through the joint efforts of the West. They all designated border delimitation, outlining both the model of Bosnia and Herzegovina as agreed upon in Dayton and Kosovo’s independence.

- Russia is now involved in carrying out hybrid warfare against pro-Western authorities in Montenegro, Macedonia, and Kosovo while its support for Bosnia’s Serb separatists poses a threat to state structures. The Kremlin’s undertakings are aimed at drawing Serbia away from Western institutions, however, the Serbs are its only ally in the region.

- Moscow skilfully profits from their conflicts with neighboring countries, mainly Kosovo, to further provoke already existing hostilities.

- Russia’s policy in the Western Balkans has suffered a number of defeats over the past three years, among which an attempted Montenegro coup and a Greek-Macedonian name change deal may be distinguished. Montenegro has joined the North Atlantic Alliance while Macedonia is still in NATO’s waiting room.

- Therefore it is expected that Russia will increase its destructive operations in the region, falling back on the Serb allies and Moscow-backed opposition forces in Montenegro and North Macedonia.

source: WARSAW INSTITUTE

source: WARSAW INSTITUTEIn addition to the former Soviet republics, the Western Balkans remains the last significant part of Europe that has not yet fully integrated with EU and NATO structures yet encompassing both Slovenia and Croatia. If their example is followed by other countries of the region, Russia is at risk of being pushed out of the region, succumbing to the economic, military, political and cultural advantage of the West. Moscow sees the geographical location of the Western Balkans at the crossroads of a united Europe and a hydrocarbon route running from south to east as its main asset. Unlike the post-Soviet zone, it is, however, incapable of entering its territory, trying its utmost to ensure the region’s neutrality and to draw it away from the EU and NATO. This is why Moscow attaches profound importance to the situation in Serbia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Kosovo, striving to exert considerable influence on the events in Serbia, the Serb-dominated part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Montenegro. Owing to historical and cultural preconditions, these countries are said to be most exposed to Russian pressure.

The Kremlin’s attachment to the Western Balkans is constantly growing, prompting Moscow to fall back on aggressive steps such as a failed coup in Montenegro. Starting in 2016, Russia boosted its active measures in the region, implementing more informal factors to its hitherto policy and employing its secret services. This is why the Kremlin made Nikolai Patrushev, a former FSB head and Secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation, its point man to the region[1] while Russia’s military intelligence agency (GRU) has enhanced its activities. Attention should be also drawn to the movement endorsed by Konstantin Malofeev, a Russian billionaire and ardent Orthodox businessman, who had backed Russia’s projects in the Crimea and Donbas. Malofeev has a number of his own interests in Serbia where he had even organized a visit of a large group of Cossacks to Banja Luka the capital of the Republic Srpska to express support for President Milorad Dodik. On March 7, 2019, Matthew Palmer, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, told journalists in an interview in Croatia’s capital of Zagreb that “Russia worked very hard to undermine the recent agreement between Greece and North Macedonia and is boosting aspirations among Bosnian Serbs to secede from Bosnia and Herzegovina.”The Western Balkans region is now where hybrid warfare between Russia and the West takes place yet with no military factors involved. Russia has not deployed any troops to the spot, unlike the United States which maintains a military base in Kosovo while NATO and the EU are in charge of supervising peacekeeping missions in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Moscow, by contrast, needs no “little green men” as it enjoys a series of other assets, including an extensive network of agents, both its own and those of the allies, and Serbian paramilitary militia whose members are bankrolled and armed by Russia.

This is all enough to sow discord across the region. Given Moscow’s enormous impact on local political, media and business circles and support from the Russian Orthodox Church, it is now able to stoke ethnic and religious tensions, block reforms, back far-nationalist and anti-Western groups and to undertake all actions preventing major regional conflicts from being solved. These have all been sparked by the historical past, political and ethnic disputes and economic rivalry, which prompted Russia to apply the “divide and rule” principle for its own interests.Russian goals

In the autumn of 2018, Kurt Volker, a former U.S. ambassador to NATO and Washington’s envoy to Ukraine, wrote in Foreign Policy that “a Balkans region that is slowly but surely becoming a normal part of Europe would upset Russia’s ambitions of keeping Europe divided into spheres of influence; of legitimizing nondemocratic, non-Western forms of top-down rule; and of creating opportunities for Russia to exercise influence through corruption, loaded energy deals, intelligence operations, and disinformation. Where Russia sees instability, insecurity, and weakness as opportunities, the EU tries to build stability, security, and prosperity.”[2]

Over recent years, Moscow has clearly increased its activity in the Western Balkans, which was equivalent to its comeback to the region in a bid to change its approach to the West. After the bloody wars of the 1990s, Moscow initially accepted the peacekeeping and stabilizing role of the Alliance. In 2003, the Kremlin decided to withdraw its troops from international peacekeeping missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, claiming that its contingent succeeded in achieving “a significant improvement in the situation.” The Kremlin did not react after Albania and Croatia joined the North Atlantic Alliance, either. This changed after Russia launched military aggression in Ukraine, followed by a further escalation of the conflict with the West, as a result of which the Kremlin started to perceive the Western Balkans as its next battlefield. In 2014, Russia abstained from the UN Security Council vote on renewing the EUFOR mandate in Bosnia and Herzegovina while a year later it has vetoed a British-drafted United Nations resolution condemning the Srebrenica massacre as a “crime of genocide.” In 2016, the Russian army mounted an offensive in the former Yugoslavia, growing stronger and posing a greater threat to the area, as exemplified by the words by the commander of NATO forces in Europe, U.S. General Curtis Scaparrotti who told a Senate committee that “the Balkans are actually the region he was most concerned about.” Only four days later, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Wes Mitchell told journalists in Pristina that Washington “does see Russia playing an increasingly destructive role in much of the Balkans in spreading disinformation, undermining democratic institutions.”

What are the main purposes of Russia’s subversive activities? Moscow’s ambition is to halt NATO and EU expansion, while in the worst-case scenario also to benefit from EU enlargement, so as to acquire the status of a regional power, or a top player, without whom it is impossible to solve any serious problems that occur in the Western Balkans. Russia intends to provoke further conflict escalation and continue its destabilizing activities, hoping to steer Western focus away from Ukraine and their activities in the post-Soviet zone. The area of the former Yugoslavia emerges as the second front for the Kremlin whose officials claim that EU enlargement in the Western Balkans, the countries of which are less affluent and tormented by both domestic and regional conflicts, will weaken the Community. In this way, Moscow strengthens a circle of its close allies within the European Union while any failure of EU and NATO expansion in the Balkans will immediately go public as a Russian propaganda tool. To counterbalance the Alliance’s enlargement, the Kremlin opts for military neutrality. One of the files that leaked from Macedonia’s counterintelligence services detailed a meeting between the Russian ambassador to Macedonia Oleg Shcherbak and the country’s top foreign ministry official Nenad Kolev. The former reportedly said Moscow’s purpose was to “create a strip of militarily neutral countries in the Balkans” covering Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia, and Herzegovina and Macedonia, the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies wrote in 2017. The Russian operation went on for a long time, within the framework of which Moscow set up a large number of regional organizations and media companies tasked with supporting the regime. As estimated by the IISS, there are 109 organizations of that kind in Serbia and at least 30 in Macedonia[3]. At the same time, the Kremlin has formed a wide network of contact with political parties, including Macedonia’s conservative opposition party VMRO-DPMNE and Montenegro’s Democratic Front. Soft power and gasRussia is using various means to develop its sphere of influence in the Western Balkans, among which soft power techniques are most effective, mostly due to common history and religion. Moscow highlights its attractiveness by promoting cultural and spiritual ties between Russia and the region. The Kremlin’s allies in this respect are the Orthodox Church, Russian oligarchs, and some local politicians. The Kremlin uses the Orthodox religion to uphold its image as a proponent of traditional family values whereas Russia-friendly media outlets and journalists broadly share anti-Western and pro-Moscow sentiments. A local editorial office of the state-run Sputnik news agency opened in 2014 in Belgrade. Its media coverage is not reliable though, as exemplified by reports by Russian television in Montenegro showing “brutal repressions of anti-NATO protests in the country” yet illustrated by footage from riots sparked in 2015 when militants of the Democratic Front opposition party tried to storm the parliament. As informed by Russian propaganda in the Balkans, the West is afraid of Russia whereas the European Union is on the brink of collapse. What is more symptomatic for the region is that Western countries, including the United States, back the Albanians in their pursuits for creating a Great Albania comprising Albania, Kosovo, and territories inhabited by the Albanians in Serbia, Macedonia, and Montenegro. The Kremlin’s propaganda proved efficient enough, as evidenced by an example of Serbian citizens, of whom 47 percent said in a survey published in 2015 that Russia provides their country with more financial aid than the European Union, although it is the latter that firmly supports Serbia. In 2000–2013, the latter secured donations worth a total of 3.5 billion euros while Russia provided a 338 million dollar-loan for Serbian railways.[4]

Another tool for extending the Kremlin’s sphere of influence in the Western Balkans consists of deepening economic and trade relations in such strategic sectors as energy, banking, commerce, and real estate. Russia focuses primarily on the energy sector, with Gazprom, Gazpromneft, and Lukoil playing key roles in Balkan oil and gas markets. Gazpromneft controlled Serbia’s largest company Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS) for over a decade; in December 2018, Gazprom’s subsidiary purchased 51 percent of stakes in Serbia’s NIS at a price of 400 million euros within a broad Russian-Serbian deal that gave Moscow control over the latter’s energy sector. The agreement provided for the NIS monopoly on oil imports to Serbia until the end of 2010. Although the Kremlin sought to prolong the contract for at least one more year, the Serbian government voiced objections to these plans, pointing to its EU commitments to open its markets. In turn, Lukoil has one refinery on Bulgarian soil that is the largest facility of its kind in the Balkans, second only to those in Greece and Turkey. Lukoil Neftohim is the biggest oil company in Bulgaria that controls both wholesale and retail fuel sales. Also, it has considerable stakes in Serbia and Macedonia.

source: GAZPROM.COM

source: GAZPROM.COMMoscow sees the Balkans as a strategically important region through which they can ship ever more Russian-sourced energy to Central Europe and Italy respectively. Between 2006 and 2015, Bulgaria and Serbia participated in the South Stream gas pipeline project, along with Bosnia’s Republika Srpska and Macedonia. In October 2009, Serbia handed over its gas sector to Russia during a visit of the then-President Dmitry Medvedev. The heads of Russia’s Gazprom and Serbia’s Srbijagaz inked an agreement that led to Moscow obtaining control over strategic gas storage facilities and the Belgrade-owned section of the planned South Stream gas pipeline. As it later turned out, the project had failed to be implemented though it has revived only recently yet its form has slightly altered. Russia intends to strengthen its influence in the region by setting up the Turkish Stream pipeline[5]. Initiated in late 2014, its concept appeared when Bulgaria withdrew from the South Stream endeavor, bowing to joint pressure from Brussels and Washington. Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev reiterated the idea of reviving Russian gas shipments to the Balkans during his recent trip to Bulgaria. The government of Boyko Borisov is in favor of building a gas connection between Turkey and Serbia running through the Bulgarian territory also to Central Europe. This is how the Kremlin seeks to boost the reliance of countries on Russian-sourced energy while offering transit fee profits.

Active measuresMoscow’s third method of setting up and consolidating its influence in the Western Balkans consists of employing Kremlin agents and local nationalist milieus to carry out destabilizing and subversive activities. While Russia has used these tools for many years with varying intensity, active measures, as they are known in the special services, and related activities have intensified over the past three years, thus since Russian Security Council Secretary and former FSB director Nikolai Patrushev took over the Kremlin’s agenda in the Western Balkans in the first half of 2016. His appointment as Moscow’s trusted man to the region shows how important this part of Europe is for Putin. Patrushev is among others tasked with centralizing Russia’s activities aimed against various Balkan countries.

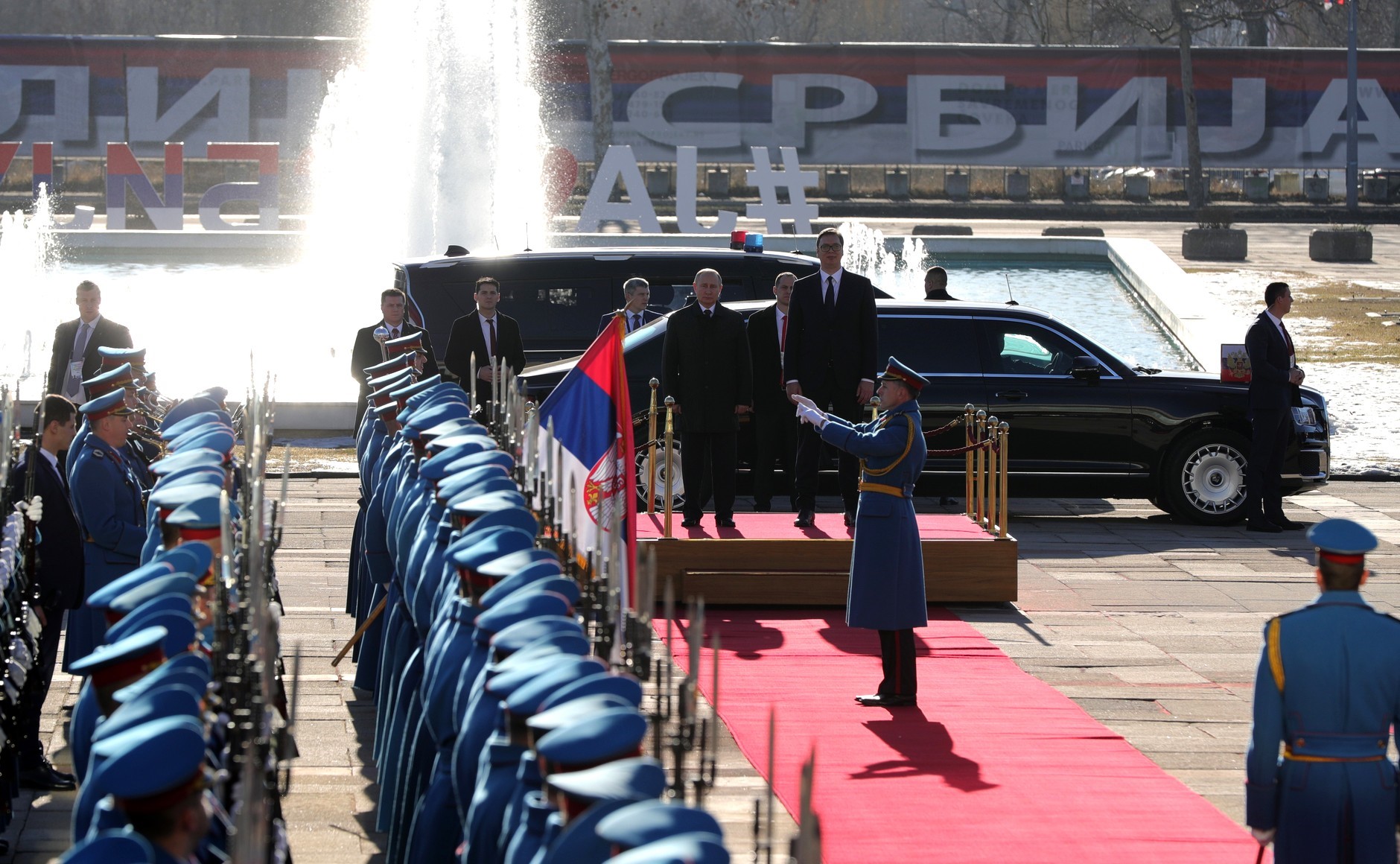

source: KREMLIN.RU

source: KREMLIN.RUActivities carried out by Russian intelligence services in the Western Balkans have intensified after a branch of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISS) was established in Belgrade[6]. A retired intelligence general Leonid Reshetnikov, who had been in charge of the Institute since 2009, had earlier served as the head of the information-analytical department of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). Known as a Balkans specialist, Reshetnikov has developed a vast network of relationships, mainly in Bulgaria and Greece where he once served as a Soviet and Russian intelligence agent, but also among former employers of the Yugoslavian special services, also maintaining close ties with the family of Slobodan Milošević. Furthermore, he largely contributed to the victory of a Bulgarian pro-Russian presidential candidate Rumen Radev. Also, much indicates that the head of the RISS might have put forward an idea to plot an attempted coup in Montenegro. Reshetnikov openly called for overthrowing Milo Djunaković, forecasting bloodshed in the country related to its accession to the North Atlantic Alliance and referring to it as a U.S.-dominated “quasi-state”. Patrushev had to thus ease the situation following the failed coup in Montenegro (read more in Section 4). After the Serbs had detained a group of GRU agents in Belgrade, Russia’s Security Council Secretary convinced the Serbian authorities to release them, insisting that Moscow had no ties to the attempted putsch in neighboring Montenegro. Although Patrushev managed to handle the situation (even if the identity of agents was later disclosed while revealing that the Russian authorities had been aware of the plot), Reshetnikov was relieved from his responsibilities. A few days after information about the attempted coup and expelling the GRU officers from Serbia was made public, Vladimir Putin dismissed Leonid Reshetnikov, replacing him with a former SVR head Mikhail Fradkov.

Russian intelligence services enjoy popularity among the Balkan authorities as exemplified by the fact that Sergey Naryshkin, who took on Fradkov’s responsibilities as the chief of the SVR, was received in 2018 by Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić during his trip to Belgrade. As stated in an official communiqué the SVR issued after the meeting, “both parties stressed the need to comply with standards of international law while solving regional conflicts.” Naryshkin and Vučić discussed cooperation between Russia’s SVR and Serbia’s Security Intelligence Agency (BIA). Naryshkin held meetings with the chairman of the Serbian Parliament and the head of the local Orthodox Church. It is rare for the president to welcome a head of a foreign secret service, which confirms a special relationship between both countries, and the decisive role played by Russian services in Serbia. In 2017, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister and senior FSB officer Oleg Syromolotov – responsible for counter-terrorism cooperation – eagerly encouraged his Serbian counterpart to strengthen cooperation with Moscow. The Kremlin is trying its utmost to take advantage of Belgrade’s fears of a plausible terrorist threat from the Muslim community inhabiting Kosovo, Albania, and Bosnia.Russia is involved in backing Western Balkan organizations, examples of which are Montenegro’s Democratic Front or Macedonia’s VMRO-DPMNE, which serve its own interests. Moscow also trains and bankrolls local paramilitary groups, a “tradition” that dates back to the early 1990s when Russian “volunteers”, usually supervised by Russian services, arrived in the former Yugoslavia to fight at the Serbian side. A group of one hundred Russian fighters was permanently deployed there between 1992 and 1995 where they also took part in an ethnic cleansing that struck the Serbian town of Višegrad. Its core consisted of a few individuals from St Petersburg, whose trip to the Balkans was facilitated by the firm Rubikon under the supervision of the Russian Federal Counterintelligence Service, or the immediate predecessor of the FSB. The volunteers could not perform military operations without the consent and commitment of Russian authorities and special services. After two decades nothing has changed but the direction, as these were the Serbs who arrived in Donbas to help the Russians. Hundreds of Serbs acquired combat experiences and the Russian services profited from an extensive network of contacts they had gained in local circles to use them later while performing operations in the Western Balkans, an example of which was the attempted coup in Montenegro. Back in October 2016 in Moscow, Leonid Reshetnikov hosted the “Atamans of the Balkan Cossack army”, a pro-Moscow union of veteran-volunteers from recent wars, including those in the former Yugoslavia, Caucasus, and Eastern Ukraine. Established in September 2016 in the Montenegro town of Kotor, the organization is headed by Victor Zaplatin, Balkan Representative of the Donbass Volunteers’ Union, and one-time commander of Igor “Strelkov” Girkin during their stint as pro-Serbian volunteers in the Bosnian war of 1991-1992. Zaplatin and Malofeev’s associate Alexander Boroday established the Serbian branch of the “Donbass Volunteers Union” in November 2015 in Belgrade.

Pro-Russian organizations in Serbia include the Radical Party, the Democratic Party of Serbia (DPS) and the “Dveri” movement while among the most well-known extremist organizations, there are Obraz and Nasi, the leader of the former, Mladen Obradović, is an expert of the RISS. In 2012, the Serbian Constitutional Court banned the activity of the far-right Obraz. In turn, ultranationalist groups such as the Zavetnici, Balkan Cossacks and the Night Wolves, a Russian nationalist biker gang, are often hosted by the Russian House in Belgrade, an agency of Russia’s Federal State Agency Rossotrudnichestvo. As he had done in 2014 and 2015, during a visit to Belgrade in December 2016 Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov met members of the Serbian nationalist and pro-Russian organization Zavetnici, from the ranks of which the participants in the October coup were recruited according to Montenegro’s prosecutor’s office. In 2012, Russia also established a humanitarian response center in Niš in southern Serbia in close proximity to the borders of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Kosovo, and Montenegro, which was where a militia called Serbian Honour was allegedly trained.[7]

Montenegro

The failed coup in Montenegro of October 2016 has emerged as an example of Russia’s ever less effective attempt to employ active measures in the Western Balkans. Known as “Little Russia” only a few years ago, a popular destination for many Russian tourists and a favorite country of Moscow-backed oligarchs, Montenegro is now at the forefront of the anti-Russian camp in the Balkans. Such a prompt shift in Podgorica’s policy has come as an aftermath of the attempted coup of October 2016 when GRU agents used members of Serbian nationalist groups to overthrow the Montenegrin government, impeding the country’s bid to join NATO. Montenegro became a member of the North Atlantic Alliance only six months after the failed plot, this way marking a geopolitical breakthrough. Unlike other countries of the former Yugoslavia that integrated into either NATO or the European Union, Montenegro has maintained its Orthodox traditions while upholding its close ties to Moscow for over two centuries.

Inhabited by 600,000 people, Montenegro is the smallest among the countries of the former Yugoslavia. The Russian-Montenegrin relationship dates back to the early 18th century when Moscow offered support for its ally fighting against the Turks. It gradually intensified and today the Russians see the Montenegrins are considered the second friendliest Western Balkan nation only to the Serbs. In 2006, Montenegro separated from the state union with Serbia, becoming a fully independent state. Perceived as a Russian ally, it emerged as the best place for Moscow-backed investments. The Russian share in Montenegro’s GDP increased to over 5 percent by 2015 while over 7,000 Russians have permanently settled in the country. Also, the Russians gained control over 40 percent of the Montenegrin real estate market, especially dwellings located along the seashore. Tourism accounts for 20 percent of Montenegro’s GDP with every fifth visitor coming from Russia.Milo Djukanović, a politician who ruled the state for many years and expressed criticism of Milošević’s far-reaching concessions towards the West, made when negotiating peace accords in Dayton, became aware of the ever-changing geopolitical situation, which inspired him to make a key decision to join the stronger camp. In early 2014, Djukanović risked losing all benefits his country received as part of cooperation with Russia, including those related to tourism, trade and real estate, and launched Montenegro’s efforts to accede to the Western structures. In March 2014, Podgorica joined the EU sanctions regime against Russia and voted in the UN General Assembly for a resolution on Crimea, which condemned the annexation of the peninsula. In April 2014 Djukanović traveled to Washington and told Vice President Joe Biden that NATO needed to expand further east in response to the Ukraine crisis. He also turned down Moscow’s invitation to take part in the Victory Day celebrations in Moscow on May 9, 2015. To make matters worse, some media reported that Russia allegedly demanded that Montenegro facilitate access to a naval base at Bar in case Moscow lost its military foothold in Syria. Djukanović got rid of all officers who endorsed Moscow’s activities; most purges took place in the state security apparatus, which was heavily infiltrated by the Russians. In late 2014, the head of Montenegro’s National Security Agency was relieved from his post, as was the vast majority of the staff.

In December 2015, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov threatened that Russia would take “retaliatory measures” in case Montenegro acceded to the North Atlantic Alliance. Prompted by Russian oligarch Konstantin Malofeev, Moscow launched activities aimed at destabilizing the small Balkan country. In September 2014, at an international gathering in Moscow devoted to “traditional family values” and sponsored by the businessman, the billionaire hosted Strahinja Bulajic, a Montenegrin MP known for his anti-NATO positions. A few months later, Bulajic became a member of the leadership of the Democratic Front coalition. In 2015 and 2016, he organized protests against the “NATO mafia”. Hostile to the West, a part of Montenegro’s opposition forces representing the Democratic Front (DF) was bankrolled by Moscow to run an election campaign. In June 2016, the front’s main NOVA and DNP parties and Putin’s United Russia signed an agreement establishing political cooperation between the two states and further promotion of Russian message in the Balkans. Also, the latter maintains close ties with the Russian nationalist party Rodina. Throughout 2016, Malofeev’s web-TV channel Tsargrad.tv devoted much air time to Mandić and Knežević, both of whom are the leaders of the Democratic Front. Back in February 2016, Mandić predicted massive rallies against Montenegro’s accession to NATO to take place sometime soon. He said that at his meeting with Duma speaker Sergey Naryshkin, he was promised that pro-Russian forces in Montenegro “can count on Russian support.” Six months later Naryshkin was appointed chief of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). The main driving force behind the anti-NATO campaign was the right-wing New Serbian Democracy (NOVA) party. In addition to being widely represented in the Montenegrin parliament, it enjoys large support from ethnic Serbs. The party’s agenda is referred to as pro-Serbian, anti-NATO and pro-Russian while among its members is a large group of former proponents of Miloševic and his policy. Protests were also attended by the small Movement for Changes political group. Srdjan Milić, a leader of Montenegro’s opposition Socialist Party, claimed that NATO’s invitation to join its structures “presents aggression in peace, stability, and security of our country’s citizens.”

An aggressive Russian-funded campaign of the National Front and other anti-NATO parties raised the political temperature of the dispute ahead of the key 2016 elections. A potential failure of Djukanović’s ruling team could put to a halt the country’s ambition to join NATO. Having assumed that the Western option would eventually prevail, Russia’s GRU drew up a plan to derail Montenegro’s accession to the Alliance while overthrowing the government. Key roles were to be played both by Serbian far-right activists and members of the Montenegrin opposition. Russian military intelligence services recruited Alexander Sindjelić, a Serbian former convict who had fought in 2015 on the side of separatists in Eastern Ukraine, and was the leader of a paramilitary organization called the Serb Wolves, to take a lead in the plot. The operation was launched only after “Shirokov” and “Popov”, or two GRU officers, arrived in Belgrade. They were top conspirators while Sindjelić, who served as an important link to the plan, contacted and recruited two of his fellow compatriots. Mirko Velimirović, a former police officer, was tasked with procuring weapons and premises while maintaining constant operational contact with a man named Nikola aka Bratislav Dikić, a former chief of Serbia’s Special Police. As the leader of the Patriotic Movement of Serbia (PPS), Dikić disposed of an extensive network of contacts in the country’s nationalist milieu, from which he hired militia members. Much indicates that Russia made the heads of the Democratic Front part of the conspiracy. A day ahead of the election, the party stated its intention to organize a rally in front of the parliament building on the evening of October 16 after the results were announced. A group of Sindjelić’s trusted men, disguised as policemen, were supposed to mingle with the crowd. To avoid fatal mistakes, they were to wear blue ribbons. As planned, one of the Front’s leaders would take the stage and trigger the crowd and the terrorists to storm Parliament by force. While some conspirators would enter the building, the “policemen” would open fire on the crowd. Meanwhile, another group of plotters was to attempt to kidnap and assassinate Prime Minister Milo Djukanović.

source: KREMLIN.RU

source: KREMLIN.RU The plot was uncovered only a few days before the election took place; most of its participants were detained while Serbia extradited some of them to Montenegro. Although GRU officers who were in charge of the operation managed to flee the country, Montenegrin services, assisted by their Western peers, quickly identified who actually stood behind the plot. “There is not any doubt that it was financed and organized from different sources or different parts of Russian intelligence, together with some Montenegrin opposition parties, but also under the strong influence of some radicals from Serbia and Russia,” Montenegrin Defense Minister Predrag Bošković told The Telegraph.[8] On March 12, 2017. Boris Johnson, who served as British Foreign Minister at that time, said in an interview for the ITV television channel that “what we do have is plenty of evidence that the Russians are capable of doing that and there is no doubt that they’ve been up to all sorts of dirty tricks […], an attempted coup in a European state and possibly even an attempted assassination of the leader of that state.”[9]

Montenegro eventually integrated into NATO structures. The state’s army comprises only 2,000 servicemen while the republic commits 1.66 percent of its GDP to military expenditure. Yet its accession to the North Atlantic Alliance sent out a clear signal to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia as two potential candidates to join the Treaty. The Kremlin is still pushing for destabilizing Montenegro by regularly employing the Democratic Front whose members obstruct the parliament’s work and draw people into the streets. Milan Knežević, head of the Democratic People’s Party, said “the Montenegrin regime has decided to join NATO against the will of the people as well as to impose sanctions on Moscow.” As announced by the Democratic Front, it will enter into any cooperation provided that the other party binds itself to sign a declaration of Montenegro’s pull-out from all restrictions imposed on Russia so far, the text of which was agreed upon with representatives of United Russia and the Russian Foreign Ministry. Opposition parties are financed by Oleg Deripaska, a Russian businessman who lost his plant in Podgorica as a result of a ruling by a Montenegrin court. Russia’s foreign policy in the Western Balkans is aided by the Serbian Orthodox Church, which prompted Djukanović to establish its fully independent Montenegrin counterpart. In response to Moscow’s aggressive actions, the government in Podgorica drafted a list of 150 Russians to be banned from entering Montenegro. Among them are Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, and Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev.Macedonia

Russia’s employment of special measures also acted to its detriment in Macedonia. Long-Term destabilization processes and ever-growing conflicts with the Albanian minority eventually led to the fall of the Gruevski government. This paved Skopje’s way to reach an agreement with Albania and, more importantly, also to put an end to a long-lasting Macedonian-Greek dispute over the country’s name. Changing its official name to North Macedonia fostered the country’s attempts to join NATO and the European Union. Moscow needed, therefore, to swallow a bitter pill as Athens, which has traditionally passed as one of Russia’s greatest allies in both NATO and the European Union, expelled a group of Russian diplomats and bilateral relations between the two states deteriorated, a result of efforts made by Russian agents to influence Greece’s decisions. At the beginning of February, the Republic of North Macedonia signed an accession agreement with the North Atlantic Alliance. Now the document needs to be ratified by the parliament of all NATO members, then North Macedonia can expect to join NATO by 2025.

source: KREMLI.RU

source: KREMLI.RUThe centre-right VMRO-DPMNE party ruled the country between 2006 and 2016 while its leader and Macedonia’s former prime minister enjoyed considerable support from the Kremlin. Revelations about a mass wire-tapping scandal resulted in a wave of anti-government protests. It was not until the end of 2016 that Gruevski finally succumbed to pressure. Although his party won the snap election of December 2016, it failed to secure a majority. An initiative of Social Democrat politicians who agreed to Albania’s federalization requests in exchange for support for its actions was vetoed by the president as he expressed his support for VMRO-DPMNE. The situation in the country was at a standstill for the next few months. Anti-corruption riots rapidly revealed its ethnic character. In April 2017, members of nationalist groups stormed the parliament and attacked Social Democrat MPs. A two-year period of Macedonia-EU mediation, in which both President of the European Council Donald Tusk and EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini took part, failed to produce any tangible results. A breakthrough happened after a senior U.S. diplomat travelled to Skopje, which highlighted Washington’s considerable influence exerted on Albania whose authorities eventually abandoned all arguments referred to as unconstitutional by right-wing political parties. After overcoming a serious political crisis, Macedonian decision-makers managed to form a center-left coalition supported by two Albanian parties. Macedonian Prime Minister and Social Democratic Party leader Zoran Zaev strove to open the doors to Skopje for EU and NATO membership. His alliance with the Albanians, who account for about 25 percent of the country’s two-million people, was scoffed at by local nationalists and staunch proponents of the VMRO-DPMNE party.

Shortly after Zaev had been appointed Prime Minister in late May 2017, classified data gathered by Macedonian intelligence services leaked to the media, according to which Russian diplomatic and intelligence services had long sought to destabilize Macedonia while hindering any Western influence in the country. Macedonia eventually became the target of “strong subversive propaganda and intelligence activity”, according to a briefing prepared earlier this year for Vladimir Atanasovski, director of Macedonia’s administration for security and counter-intelligence (UBK). The document is a collection of secret reports based on wire-tapping materials, direct observation methods and informants’ reports. An anonymous source in Macedonia’s new government handed the files to the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). The joint journalistic investigation took place with the participation of the Macedonian NOVA TV television channel and the Serbian KRIK publishing house.

For the last nine years, Macedonia has been “undergoing strong subversive propaganda and intelligence activity” directed from the Russian embassy, the leaked files said. Russia employed the methods of so-called soft power, “as part of the strategy of the Russian Federation in the Balkans, the goal is to isolate Macedonia from the influence of the west.” Also, Russia’s foreign policy in the region is in tight correlation with its energy strategy to control “strategic energy resources through partnership with the Balkan countries and ultimately to make Macedonia exclusively dependent on Russian policy,” the document stated. That operation began in 2008 when Greece blocked Macedonia’s pursuit to join NATO, disagreeing with the use of Macedonia as the country’s name. Three agents from Russia’s SVR are based in Skopje, and overseen by the SVR’s sister station in the Serbian capital, Belgrade, the leaked documents said. Also, the Russian embassy in Skopje was to become home to four GRU spies, with their activities coordinated from the service’s base in Sofia. Furthermore, journalists from Russia’s state news agency TASS and representatives of Rossotrudnichestvo worked with Russian intelligence, activities of which were coordinated by the Russian embassy in Skopje. Moscow has long been involved in recruiting both former and present army and police officers in a bid to train efficient personnel to be subsequently deployed in the event of a civil war. The Kremlin pushed the idea of the “pan-Slavic identity” of the Russian and Macedonian nations whereas Russian consulates in the towns of Bitola and Ohrid function as “intelligence bases” yet are officially registered as cultural institutions. Russian agents, which were offered support from Serbia’s BIA intelligence services, have offered cash to Macedonian media to spread disinformation, the files alleged. Moreover, Belgrade backed Macedonian nationalists who voiced both pro-Russian and anti-Western attitudes. Also, Serbian activists are part of the Kremlin’s strategy: counterintelligence services eavesdropped on the officers of Serbia’s BIA intelligence that backed both Gruevski and Macedonian nationalists. In 2013, its agents launched an operation aimed at following a certain man known as Goran Živalžević who was to instruct a pro-Russian Macedonian MP and the leader of the Democratic Party of Serbs Ivan Stojlković. Dubbed as Macedonia’s most vociferous pro-Russian, he held regular meetings with Kremlin-friendly politicians in neighboring Montenegro, with those to whom the Macedonian counterintelligence referred to as “Russian agents”. Also, Stojlković and a BIA employee arranged a number of publications denigrating Zoran Zaev.

Russia’s influence operation was doomed to fail; Gruevski lost power while a new ruling team quickly reached a name change deal with Greece, prompting Athens to unblock Macedonia’s bids to integrate into Western structures. Yet Moscow had no intention to make any concessions, by fueling the Macedonian opposition’s destabilizing activities in Skopje and simultaneously deploying its agents in Greece. Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev accused Ivan Savvida, a Russian-Greek businessman, of inciting violence ahead of a referendum that would allow the country to join NATO. After NATO had formally invited Macedonia to join the Alliance on July 11, 2018, Athens confirmed reports of having expelled two Russian diplomats and banning them from entering the country’s territory. They allegedly tried to torpedo the agreement concluded by Athens and Skopje on June 17, 2018. Under the deal, Skopje will be obliged to change the country’s name to the Republic of North Macedonia whereas Greece would give its neighbor a green light to join such institutions as NATO and the European Union. In order to hinder the implementation of the agreement, the Russians probably wanted to use the nationalistic clergy of the Greek Orthodox Church. Apparently, Russia’s activities must have been very harmful, since the government, which had been traditionally considered as the most Moscow-friendly among many other members of NATO and the EU[10], eventually decided to take such a drastic step. On the occasion of tossing out the Russian diplomats, Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias revealed that he got a call from Sergei Lavrov when the deal with Macedonia had already been finalized. Russia’s Foreign Ministry allegedly admitted that Moscow would obstruct the Greek-Macedonian agreement by performing appropriate actions in Skopje. Such a claim has been confirmed by some other moves made in the following weeks. When Macedonia’s Parliament voted on June 20, 2018, to ratify the deal with Greece, the agreement was vetoed by the country’s president Gjorge Ivanov. He is strongly connected to the VMRO-DPMNE party that aims to overthrow the left-wing government and regain the power it had lost. However, under Macedonia’s Constitution, the president is obliged to sign a bill if the parliament adopts the same act for the second time. On July 5, 2018, the proposed law was accepted by the majority in the country’s parliament, including left-wing parties as well as representatives of national minorities. However, this had to be approved in a nationwide referendum.

In September 2018, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said Macedonia “has proven a reliable security partner and a valued contributor to global peace and security.” Also, Mattis noted that Russia launched a propaganda campaign aimed at influencing the outcome of a referendum in Macedonia on changing the country’s name. His concerns over Russia’s meddling materialized during a referendum held on September 30, 2018. Due to the poor turnout (39 percent), the voting could not be considered valid though 91 percent of all votes were in favor of changing the country’s name. In December 2018, Macedonia’s parliament passed an amendment to the constitution, under which the country’s name was changed to North Macedonia, which was in line with an agreement with neighboring Greece. In its statement, the Russian Foreign Ministry claimed that the name change process imposed from the outside (implicitly by Western countries) in order to force Skopje to join NATO. Macedonia’s new name went into force on January 25, 2019, when the Greek parliament ratified an agreement 153 to 146 on the change. This marked a milestone, permitting North Macedonia to make a step towards a more stable region and a joint EU-NATO victory in the Balkan game.

source: WIKIPEDIA.ORG

source: WIKIPEDIA.ORG Moscow will continue its pursuit to destabilize North Macedonia through the VMRO-DPMNE party, whose leader fled to Hungary to avoid being detained, and other political factions. Moscow also looks to exert influence on Macedonia by employing a large group of well-organized supporters of the Vardar Skopje handball club owned by a Russian businessman Sergey Samsonenko. Both before and during the 2018 referendum, they held rallies against Macedonia’s new name and its potential membership in NATO and the EU. Moscow can count on the Macedonian Orthodox Church as well. What happened in Macedonia is an example of how the Kremlin blames the West for meddling in the domestic affairs of the Balkan states, while provoking them itself and seeking to uphold its image of a credible mediator in internal disputes that is capable of handling matters much better than Europe and the United States. Furthermore, the Macedonian crisis depicts how the Kremlin employs ethnic and religious prejudices while threatening the Slavic nations with a concept of “Great Albania”. In a press release published in 2017, the Russian Foreign Ministry wrote that “attempts, which are actively supported by EU and NATO leaders, are being made to make Macedonians accept the ‘Albanian platform’ designed in Tirana.” Russian propaganda does not hesitate to take advantage of statements such as those delivered by Albanian Foreign Minister Ditmir who said during his visit to Washington in April 2017 that his country is “a bastion against Russia’s influence in Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Bosnia, and Croatia.”[11]

KosovoThe concept of Great Albania leads to sleepless nights for the country’s neighbors, particularly Serbia which lost Kosovo in the aftermath of the bloody conflict and armed NATO intervention. Given the fact that the countries are connected historically and ethnically, Russia is capable of setting Balkan states against each other. This is sometimes facilitated by the inaccurate statements of Balkan politicians, including that of the Albanian prime minister. In 2017, Edi Rama said that “that a union between Albania and Kosovo” cannot be ruled out if EU membership prospects for the Western Balkans fade.” Both Serbia and Albania have declared their willingness to accede to the European Union and are official EU candidate countries.[12] This was lambasted by the authorities in Belgrade who said a new war might break out in the Balkans if Albania attempted to form a union state with Kosovo and the West had no intention to reject such plans. It is in Russia’s interest to uphold the Serbian-Albanian conflict; Moscow and Belgrade were among the capitals that did not recognize the 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence. Russia’s Foreign Ministry said in a comment that “under the guise of hypocritical talk about the need to stabilize the region under the NATO umbrella, the very foundations of stability are being shaken; a new policy course has been adopted to redraw the borders in the Balkans, which will inevitably increase the potential conflict.” Also, the Kremlin expressed sharp criticism over the lack of response from the European Union and the United States to attempts of reviving the idea of Great Albania.

As in Montenegro and Macedonia, Russia aims to take steps to destabilize the already tense relations between Belgrade and Pristina, as exemplified by a risky operation carried out in late 2016 and early 2017. This started back in December 2016 when a wall was built in Mitrovica, Kosovo, preventing the bridge across the river dividing the town from being re-opened. In early January 2017, Serbia issued an international arrest warrant for former Kosovo Liberation Army Commander and former Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj on war crimes charges. His detainment in France sparked a wave of protests from the Kosovo Albanians. Belgrade’s actions are to a great extent influenced by the Kremlin’s decisions, as exemplified by revoking arrest warrants against Milošević’s widow Miriana Marković and oligarchs Bogoljub Karić and Miroslav Mišković. They all fled to Moscow. Also, pro-Russian activists have intensified their actions in Serbia. Known for his close ties to the Russian special services, Nemanja Ristić, a plotter of the attempted coup in Montenegro wanted by the country’s authorities, insisted that Russia would hammer out a deal with President Donald Trump while the Russophiles in his country were ordered to “beat the enemy”, or Albania, NATO and the EU. Although detained by Serbian police officers, Ristić was released shortly afterward. The conflict reached its apogee after a direct railway connection from Belgrade to Kosovska Mitrovica was restored after eighteen years, launched without Kosovo’s prior agreement. On January 14, 2017, an unusual train set off from the Belgrade station. Painted in Serbian colors, it consisted of two wagons bearing signs reading “Kosovo is Serbia” in 21 languages, including Albanian. The train was a gift from Russia. Decorated on the inside with Serbian Orthodox images, it carried a group of journalists, politicians, and social activists, among which was Miša Vašić, an activist of the far-right 1389 Movement. Informed by Belgrade, the Kosovo authorities ordered special police units to be deployed along the border, preventing the train from reaching its final destination, however, it was halted in Raška, a border city on the Serbian side. Belgrade even talked about a “terrorist” conspiracy organized by “Albanian nationalists”. While the train was still on its way to Kosovo, an extraordinary session of Serbia’s National Security Council was convened in the headquarters of the Serbian General Staff. Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić said the two sides were on the “brink of war,” and threatened to send in the army if “they start killing Serbs.” The train was finally stopped after an intervention from the EU and NATO. But the incident fuelled Kosovar fears of repeating the “Crimean scenario” that Belgrade would implement against northern regions of Kosovo inhabited mainly by the Serbs. Occupying even a small area of Kosovo with the aim of ensuring “civil protection” would be extremely uncomfortable for NATO forces, forcing the Alliance to face a choice between an armed intervention, followed by the further escalation of the conflict, and inaction along with the loss of credibility. If the Serbs entered Kosovo without a U.S. reaction, this would spark uproar among the Albanians, probably prompting them to cause riots similar to those that took place in March 2004 when a wave of social unrest erupted in Kosovo, during which its participants burned Orthodox churches and monasteries and attacked Serbian villages.

Brussels is pushing for Belgrade and Pristina to conclude an agreement on the issue, an aim that sparks dissatisfaction among the Serbian authorities. Sooner or later, it is to be expected that Russia will try to go back on the Belgrade-Pristina deal on the territorial swap. In August 2018, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and his Kosovar counterpart Hashim Thaçi allegedly agreed on handing four Serbian-dominated municipalities in northern Kosovo over to Serbia’s sovereignty, with Pristina receiving Albanian-majority Preševo and Bujanovac. Yet the European Union does not intend to endorse the plan, being a dangerous example of border correction, hoping that Serbia and Kosovo eventually abandon their mutual claims and solve the dispute in line with EU legislation after both countries join the community. Although Thaçi rejected the idea of border correction, it seems that the deal might still be on. Aleksandar Vučić said on March 4 that Serbia will accept independence only if Serbia gets something concrete in return. Interestingly, Moscow has acknowledged that independent Kosovo is a fact that needs to be taken into account while the Kremlin may benefit from a dialogue with Pristina. In November 2018, speaker of Parliament of Kosovo Kadri Veseli met with Vladimir Putin in Paris while Hashim Thaçi said Kosovo “would open an embassy in Moscow once Pristina signs an agreement with Belgrade to normalize relations.”

Serbia

Russia’s last foothold in the Western Balkans remains Serbia, or more precisely the Serbs; it is because Moscow holds close ties to Belgrade while enjoying even greater support from the Republika Srpska, which is part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Kremlin takes advantage of Serbia’s isolation in the region and its conflicts with Croatia and Albania. Not incidentally, when in early 2016 Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin offered a gift to Vojislav Šešelj, a Serbian nationalist leader, in which Crimea was presented as part of Russia, he expressed hopes that Šešelj would make a similar present depicting Kosovo as a region of Serbia. Russian media and experts reminded the Serbs that they had already suffered defeats in Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia, and then they lost their own province, Kosovo. The Russians have underlined the weakness of the Serbian army in the past decades and its growing potential in recent years thanks to some Russian help. Moscow is fueling disputes between Serbia, its neighbors and the West because it is aware of the fact that Belgrade’s accession to the European Union will be equivalent to its recognition of Kosovo as an independent state, thus significantly diminishing Russia’s role in the country. Moscow benefits by the fact that the Serbs are the most Kremlin-friendly nation in the region while 80 percent of the Serbs acknowledged Putin as the world’s most powerful leader.

Russia sees Serbia as a comfortable ally to be employed with the aim of destabilizing the situation in neighboring countries. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbian leader Milorad Dodik intends to dismantle the federal state from the inside. In Macedonia, the Russians were aided by the Serbian intelligence agency while in Montenegro Serbian far-right extremists played a key role in the failed coup. A Russian-Serbian humanitarian center that opened in the Serbian town of Niš, became the heart of the Russian services’ activity. In 2009, Moscow and Belgrade inked a deal establishing a “logistics center for rapid responding to natural and industrial disasters.” Never before had any non-former Soviet republic (and an aspiring EU candidate) agreed to host a Russian chemical protection battalion and firefighting battalions. The agreement paved the way for the long-term deployment of uniformed Russian personnel, helicopters and dual-purpose vehicles to Serbia. When the Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center was established in 2012, Moscow gave its word that the facility’s goal was to prevent natural and industrial disaster while having no political objectives. It was, however, clear that Moscow installed its military and intelligence personnel under the guise of a humanitarian relief center. This was corroborated by U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs Hoyt Brian Yee who said in May 2017 that the institution might also serve to influence public opinion. Not incidentally, it was founded in the immediate neighborhood of the borders with Macedonia, Bulgaria, Kosovo, and Montenegro. The West accused Moscow of establishing the facility to enable the country’s intelligence services to conduct operations covering the entire Southern Balkan region. Niš will be the place where Serbian paramilitary groups, including the Bosnian Serb militia Serbian Honour, are to be trained.Back in 2013, Russia and Serbia inked a bilateral defense cooperation agreement, committing their armies to conduct regular joint military drills. Also, Serbia has been granted observer status in the Collective Security Treaty Organization, a military pact that gathers part of the former Soviet republics under the auspices of Moscow. Serbia has purchased Russian-made weapons to modernize its army: in 2016, Moscow said it would give Belgrade six MiG-29 jets, 30 T-72 tanks, and 30 BRDM 2 reconnaissance vehicles. Further Serbian-Russian cooperation was fostered after Vučić’s victory in the presidential election on April 2, 2017. The candidate for the conservative Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) won in the first round, receiving over 50 percent of all votes. Vučić, who had served as Serbia’s Prime Minister since 2014, managed to become the country’s most powerful politician. His message was skilfully delivered to both pro-Western and pro-Kremlin Serbs, including far-right nationalists. The partnership between Moscow and Belgrade, which is inspired by a common history and religious ties, focuses on security matters including the military reinforcement Russia sends to its Serbian ally. In September 2017, Serbia took part in the Collective Security Treaty Organization exercises held in Kazakhstan. In 2015, Belgrade began to participate in a joint Russia-Serbia-Belarus Slavic Brotherhood tactical drills, the first edition of which was launched in Russia’s Krasnodar Krai in 2015. The second one was carried out a year later in Serbia, coinciding with civil defense exercises in neighboring Montenegro while the third edition took place on a training ground near the Belarussian city of Brest. The fourth one was once again held in June 2018 in Krasnodar Krai. After the Serbian president returned from his first trip to Russia as head of state in December 2017, Serbia’s Defense Minister Aleksandar Vulin told state TV that during Vučic’s visit to Moscow, the leaders of both countries agreed on a “high level of military cooperation”. Vulin informed that Belgrade not only wanted to buy six Mi-17 helicopters, but it was also interested in forming an overhaul base for the Russian choppers. It would give Russian military personnel a presence in the region. Serbia and Russia have also talked about supplies of Buk-M1 and Buk-M2 missile systems and possibly S-300 air defense systems from Belarus.

source: KREMLIN.RU

source: KREMLIN.RUThe problem is that Serbia has been on the path to join the European Union while stressing that it is not interested in joining NATO and maintains that it opts for “military neutrality.” Serbia first applied to join the European Union in 2009. Belgrade’s talks with Brussels kicked off in 2014 and they hope to complete them by 2020, however, a positive outcome will not result from Serbia’s attitude towards Russia. Belgrade did not impose sanctions on Russia although it was a necessary prerequisite for all EU candidate countries. Shortly after announcing Vučić’s electoral victory, the president-elect emphasized that the Serbs voted simultaneously for joining the European Union and maintaining close links to Russia. Serbia, which was also a special guest of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum 2017, “will always remain a friend of Russia,” Prime Minister Ivica Dačić said. He also stressed that his country would never join in Western restrictions against Russia, striving to keep military neutrality despite the country’s bid to become a member of the European Union. Establishing mutual trust is seriously impeded by Russia’s actions like the failed coup in Montenegro. Arresting a group of Serbian citizens, part of whom came from Kosovo, was sharply criticized by Aleksandar Vučić who served as the country’s Prime Minister at that time. However, if he had declined to enter into cooperation with Montenegro, it might have aroused suspicion that Serbia’s authorities or at least intelligence services had known about the plot. At a special press conference on October 24, 2016, Vučić announced that “foreign special services, from both the east and the west”, had been operating on Serbian territory. He also confirmed that part of the action against the government of Montenegro had been launched from Serbian territory. His words coincided with the detention of several GRU spies by the Serbian counterintelligence services. Two days later, the secretary of Russia’s Security Council, Nikolai Patrushev, paid an unannounced visit to Belgrade. He said that the arrested Russian citizens acted without the knowledge of the state authorities, calling on Belgrade to release both detainees due to the friendship between the two states. Serbia believed, however, as it later turned out, Patrushev lied to his Serbian partners.

Serbia has a clear prospect of acceding to the European Union in 2025, meaning that yet another country will join anti-Russian sanctions. Vučić is trying his utmost to convince the Russians that his policy does not jeopardize their interests, which was the main topic of his conversation with Vladimir Putin in Moscow in 2018 and in Belgrade in January 2019. The current situation, however, counts against Moscow. Although Serbia, unlike its neighbors, is in no rush to join NATO, it is the European Union – and not Russia – that remains its largest trade partner. Serbia’s trade with Germany or Italy exceeds that with Russia, despite the free trade agreement the two countries inked some time ago. Serbian exports to Russia amount to 5.4 percent, compared to 15 percent to Italy and 13 percent to Germany. Although Serbia is eager to purchase Russian-made military technologies, the country’s army was outfitted according to NATO standards. Also, a number of joint NATO-Belgrade military drills jumped tenfold compared to those carried out with Russia. In 2016, Serbia and NATO reached an agreement under which Serbia committed itself to provide NATO Support and Procurement Organization (NSPO) personnel with liberty of movement around the country, which Moscow is acutely aware of. The Kremlin is doing its best to retain its sphere of influence in Serbia, treating the country as its foothold in the Balkans. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, who traveled to the region in February 2018, said many times that Serbia’s joining the European Union is not at all a foregone conclusion. He warned the Serbian government, claiming that Brussels’s calls to conform Serbia’s foreign policy to the European Union’s, as part of the country’s aspirations to join the EU, could eventually lead to a situation comparable to what happened in Ukraine.Bosnia and Herzegovina

Vladimir Putin met with President of the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina Milorad Dodik during his January visit to Belgrade. Bosnia and Herzegovina is currently the biggest hotspot in the Western Balkans. Influenced by Russian policy, the country is on the brink of an internal conflict, even risking complete disintegration. The Kremlin provides diplomatic and military support to the Bosnian Serbs. The Russians are also involved in training police staff and paramilitary militia in the Republika Srpska. There is a growing number of Russian instructors in Banja Luka’s police staff training center, an institution that has become a kind of the Russian facility in the Serbian town of Niš. Paramilitary branches are trained in “cultural centers”, run jointly by Russia and Serbia. Dodik did not hide his willingness to form a potential military alliance with Russia. Dubbed the most pro-Russian Serbian politician in the region, he met with Putin six times in the period from 2014 to 2018. In October 2018, he was again elected President of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Republika Srpska.

Dodik is building authoritarian rule while no federal government managed to be formed after the 2018 voting. A majority of local pro-Russians developed a nationalist approach. Dodik regularly threatens to hold an independence referendum, pushing forwards the concept of Great Serbia consisting of the Serbian part of Bosnia, Serbia, and the Serbian enclave in Kosovo. In late January 2018, South Ossetian leader Anatoly Bibilov paid a three-day visit to Republika Srpska, one of two constitutional and legal entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where he met with a number of officials, including President Dodik. In response, Georgia sent a protest note to the Bosnian Foreign Ministry. The problem is that Dodik is committed to carrying out his own foreign policy that is distinct from the one conducted by the Bosnian-Croatian federal entity and the official government in Sarajevo. source: KREMLIN.RU

source: KREMLIN.RUSince the Dayton Peace Agreement in 1995, Bosnia and Herzegovina, also referred to as BiH, consists of two autonomous state units: the Muslim-Croat Federation and Republika Srpska. Both of these entities have their own presidents, governments, and parliaments. They are connected with one another by relatively weak central institutions, including the three-member Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina which is supposed to represent three nationalities: Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic Croats, and Orthodox Serbs. Elections were held in Bosnia and Herzegovina on October 2017, while the country was visited by Russian Foreign Minister only several days before. Lavrov paid a visit to Sarajevo where he assured that Russia would try its utmost to respect the election result and would not stand up for any political party. Nonetheless, he also went to Banja Luka, the capital of the Republika Srpska, and denied his own statement delivered earlier in Sarajevo. But in fact, the visit to Bosnia and Herzegovina constituted an expression of Russia’s strong support for Milorad Dodik. After the 2018 election, Dodik refused to hold sessions in the building of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina until the flag of the Republika Srpska is not displayed in its rooms. However, such a step presents a blatant violation of Bosnian law. Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Republika Srpska does not recognize the Bosnian-NATO annual cooperation plan. All this makes it impossible to appoint a prime minister or a representative of Republika Srpska under the rotational principle. Bosniak and Croat delegates in the House of Peoples of Bosnia and Herzegovina presented Dodik with an ultimatum: he would commit himself to ink a cooperation agreement with NATO in exchange for appointing a Serb as the country’s next prime minister. They all agreed on updating the provisions of the Dayton Peace Accords. Russia provides support to Bosnian politicians who seek to liquidate the post of the High Representative who is to oversee the civilian implementation of the Dayton agreement. Dodik has long been in favor of the wider autonomy of the Republika Srpska and seeks to detach the entity from Bosnia and Herzegovina over the long term, hoping that Moscow will support his separatist plans. This is to be fostered by the dialogue on the exchange of territories between Serbia and Kosovo — meaning a precedent that would ultimately make it possible to change borders. Lavrov has never voiced support for Dodik publicly. Yet, a series of meetings he held with the leader of the Serb-dominated entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia’s Prime Minister Ivica Dačić could be interpreted as Moscow’s straightforward support for future incorporation of Republika Srpska into the Republic of Serbia.

Towards the West

Despite Moscow’s efforts to maintain its own sphere of influence in the Western Balkans and to block the region’s pursuits to integrate into Western structures, its strategic position has deteriorated over the past three years. In addition to Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, almost all countries of the region visibly limited Russia’s influence over their policies, marking a clear tilt towards the West. Moscow considers its failure in the Balkans particularly painful, all the more so that these are Slavic nations where the Orthodox religion prevails to a great extent. It is the world’s second-biggest Orthodox region, second only to the former Soviet republics. If the long-lasting tradition of friendly Balkan relations with Moscow is taken into account, which safeguarded the security of their “Orthodox Slav brothers” in fights against Muslim Turkey since the 18th century, it does not come as a surprise that Moscow felt somewhat betrayed by its Balkan partners. This could lead to more aggressive actions by Moscow carried out in this European region, which U.S., NATO, and European leaders are perfectly aware of.

Russia’s boosted presence and fears of the growing influence of Turkey and China attracted the Balkans’ interest in becoming part of the European Union. In February 2018, the European Commission adopted the Western Balkans strategy, specifying prerequisites that need to be complied with by Montenegro, Serbia, Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo before deepening ties with Brussels. At the EU-Western Balkans summit that took place in Sofia in May 2018, European Council President Donald Tusk said that the European Union and the Western Balkan states initiated the phase of practical rapprochement a day ahead of starting bilateral talks on their plausible accession. Of all states, only Serbia and Montenegro could join the European Union in 2025 while other countries remain in the EU waiting room. There is no doubt that the Kremlin will strive to take advantage of the situation because the region’s long road to the community translates into fading enthusiasm from its inhabitants. For example, in November 2009, 73 percent of people were in favor of joining the European Union, compared to only 47 percent in February 2017. Moscow feels much more threatened by NATO expansion; besides, no country of the region joined the European Union while no longer being a NATO member or at least not acceding both organizations at the same time.

The Adriatic Chart summit was held on August 1, 2017, in the Montenegrin capital, during which U.S. Vice President Mike Pence delivered a speech in the presence of leaders of NATO members Montenegro, Croatia, Albania, Slovenia and of non-NATO members: Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, and Kosovo. Pence told the volatile Western region that its future lies in the West. He reiterated the commitments of the United States to the region, urging the Balkan countries to remain “firm and uncompromising” towards Russia, calling the latter an “unpredictable country that casts a shadow from the east.” He continued, “under President Trump, we’ve been holding Russia accountable for its activities and we call on our European allies and friends to do the same”. On December 5, 2018, NATO foreign policy heads invited Bosnia and Herzegovina to submit a draft reform plan as part of its Alliance membership. Poland’s Foreign Minister Jacek Czaputowicz said that particular attention was drawn to such activities as external involvement in the situation in the Western Balkans, attempts to destabilize the region, the spread of Russian disinformation and Moscow’s aid to Bosnian separatist militias. “NATO would like [to] and will stabilize the region due to its key importance for the security of the entire European Union,” Czaputowicz was quoted as saying. In an interview for Euronews TV on February 6, 2019, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg warned against Russia’s influence, accusing Moscow of attempting to sabotage Balkan aspirations to join NATO[13]. “Russia tries to meddle, Russia tries to interfere in [the] political processes in sovereign nations. So Russia should respect the decisions made by sovereign nations, even if they want to join NATO, even though they [Russia] don’t want that,” he said.Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński – Expert at Warsaw Institute, Director of Eurasia Program

Grzegorz Kuczyński ukończył historię na Uniwersytecie w Białymstoku i specjalistyczne studia wschodnie na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim. Ekspert ds. wschodnich, przez wiele lat pracował jako dziennikarz i analityk. Jest autorem wielu książek i publikacji dotyczących kuluarów rosyjskiej polityki.

[1]. Patrushev’s liability for what happens in the Balkans clearly exemplifies the direction of Russia’s foreign policy under Putin’s regime. Particular regions or countries remain under the supervision of politicians belonging to Putin’s inner circle: for instance, Ukraine, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia are overseen by Vladislav Surkov while Rosneft’s CEO Igor Sechin accounts for Russian interests in Latin America. In the past, Russian Deputy Minister Dmitry Rogozin was the Kremlin’s trusted man in Moldova and Transnistria.

[2] https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/28/dont-let-russia-get-its-way-in-macedonia/

[3] https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-comments/2017/balkans

[4] https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/do_the_western_balkans_face_a_coming_russian_storm

[5] The Turkish Stream project provides for constructing a gas pipeline under the Black Sea bottom to link Russia with Turkey. It will consist of two lines, each annual capacity of 15.75 billion cubic meters. The first thread would be used to pump gas to cater to Turkey’s domestic consumption while the second one could serve to import energy shipments to be further re-exported to Europe.

[6] The RISS was brought into existence in February 1992 by Russian President Boris Yeltsin. In the Soviet Union, the institution’s predecessor was the former KGB Scientific and Research Institute of Intelligence Problems of the First Central Board. Not surprisingly, RISS has long served as a support for Russia’s SVR intelligence agency. It was not subordinated to the presidential administration until 2009.

[7] http://www.zurnal.info/novost/20914/milorad-dodik-formira-paravojne-jedinice-u-republici-srpskoj

[8] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/02/18/russias-deadly-plot-overthrow-montenegros-government-assassinating/

[9] https://www.politico.eu/article/boris-johnson-russia-behind-coup-plot-assassination-attempt-in-montenegro/

[10] In March 2018, when over 20 NATO members expelled Russian diplomats from their territories after the assassination attempt of Sergei Skripal, Athens did not take part in this action.

[11] https://www.b92.net/eng/news/region.php?yyyy=2017&mm=04&dd=20&nav_id=101074

[12] In 1999, Belgrade lost control over Kosovo as a result of NATO intervention. A group of 5,000 NATO troops remains in Kosovo. Backed by its Western allies, the authorities in Pristina declared independence in 2008. Although Muslim Albanians account for 92 percent of the entire population, a total of 50,000 Serbs inhabit northern Kosovo in the immediate neighborhood of Serbia. The heart of the exclave lies in the town of Kosovska Mitrovica.

[13] https://www.euronews.com/2019/02/06/exclusive-russia-trying-to-meddle-in-balkan-countries-joining-nato

The publication of the Special Report was co-financed from the funds of the Civic Initiatives Fund Program 2018.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.