SPECIAL REPORTS

Data: 5 November 2019 Author: Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse

Poland’s 2019 Parliamentary Election

Held on October 13, 2019, Poland’s general election is first and foremost a success of democracy, as exemplified by crowds rushing to polling stations and a massive rise in voter turnout. Those that claimed victory were the government groups that attracted a considerable electorate, winning in more constituencies across the country they ruled for the past four years. Opposition parties have earned a majority in the Senate, the upper house of the Polish parliament. A fierce political clash turned into deep chasms throughout the country, and Poland’s political stage reveals polarization between voters that lend support to the incumbent government and those that question the authorities by manifesting either left-liberal or far-right sentiments.

Election results

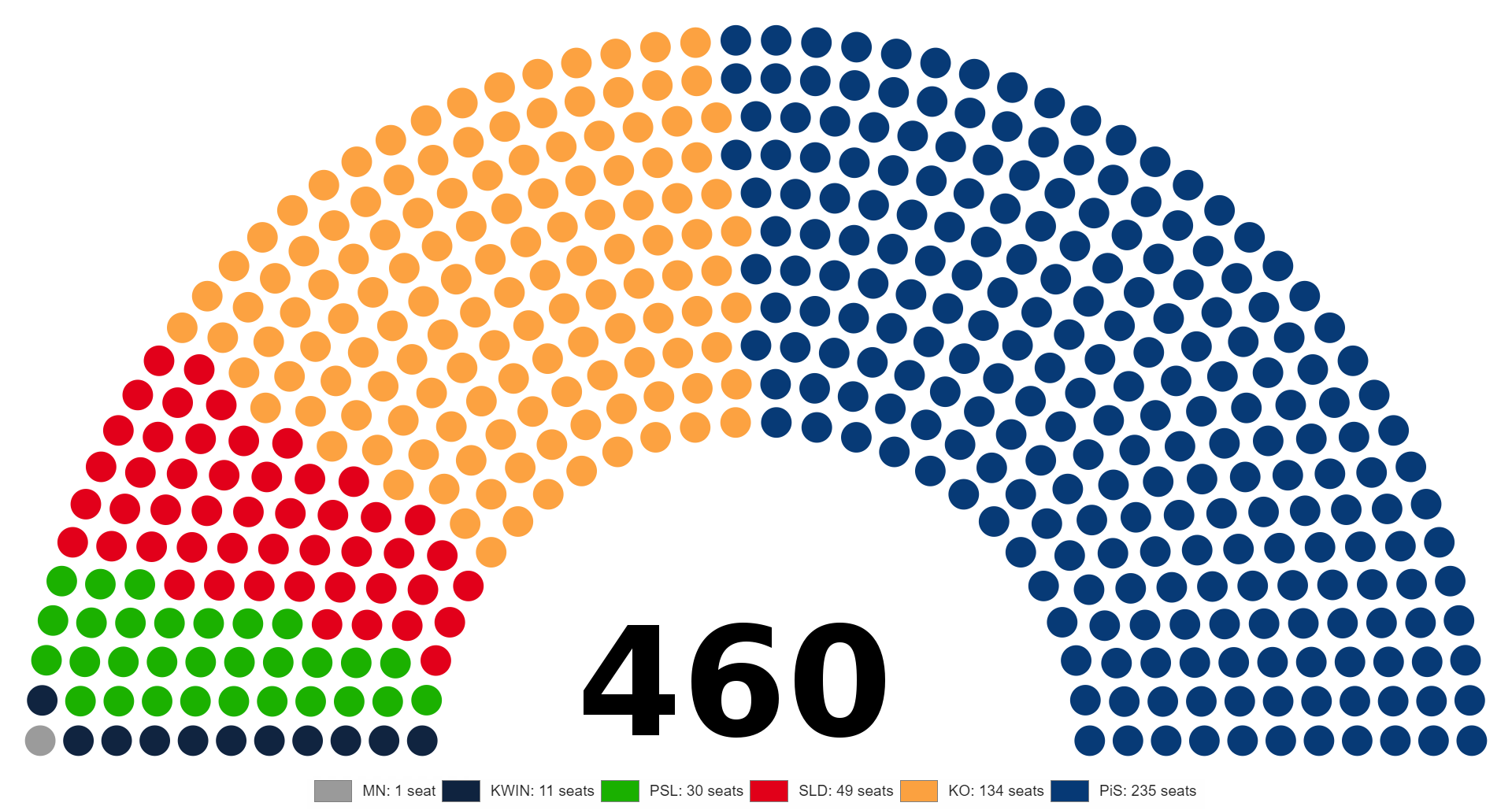

Poland’s parliamentary election in 2019 attracted the attention of Polish voters both at home and abroad while drawing media interest all over the world. At stake were the next four years in power for Poland’s ruling coalition United Right, led by the Law and Justice party (PiS)[1]. The ruling coalition won the election, taking 235 seats in Poland’s 460-seat Sejm, the lower house of the parliament. Though opposition parties, along with independent candidates, secured a majority of 52 seats in the country’s 100-seat Senate, the upper house of the parliament, it is the Sejm where the incumbents have earned a majority of five that has a pivotal role in enacting legislation and forming the country’s government[2].

The electoral success of the United Right consisted in mobilizing its supporters to a greater extent than any other Polish political groupings did. The right-wing coalition appealed to 2.3 million, or some 30 percent, more voters in 2019 than it did in 2015. In 2019, over 8 million Poles cast their ballot for the Law and Justice. Never before since 1989 –– when Poland’s transition to democracy began –– has any party earned such a high percentage of all votes (43.5 percent). What underlies the triumph of Law and Justice is that it won the election in 90 percent of the country’s countries (poviats), or territorial units being of critical importance for constituency delineation. Back in 2015, Law and Justice came first in 300 of Poland’s 380 counties, compared to a sweeping majority of 342 in this year’s general vote. The opposition Civic Coalition took the lead chiefly in the city counties.

Poland’s most prominent opposition grouping Civic Coalition (KO) came second with 134 seats of support (27.5 percent of all votes), with Civil Platform (PO) serving as the grouping’s core[3]. But –– compared to its 2015 result –– the coalition attracted a smaller number of all voters. Poland’s largest opposition party failed to accomplish its vital election goal as power remained in the hands of Law and Justice. The Civic Coalition seems the main loser of the 2019 parliamentary election.

The remaining three political groupings that crossed the election threshold may feel somehow pleased with their overall performance. The Left, a coalition of left-wing parties, won 12.5 percent as a bonus for having pulled together several smaller[4] groupings that led it to the parliament after a four-year hiatus. The second grouping that notched up a never-before-seen success is the far-right Confederation Freedom and Independence that won nearly 7 percent of all votes, doubling its electoral score compared to 2015. Thirdly, the agrarian Polish People’s Party (PSL), which ran together with the right-wing Kukiz’15 movement, was supported by 8.5 percent of voters in a move that made these two enter parliament at all. Nonetheless, in comparison to their 2015 results, both have lost large groups of voters.

The Confederation, next to the Polish People’s Party and Kukiz’15 –– the last two of which are in coalition –– stand out as the biggest competitors for Law and Justice in the country’s right wing. First and foremost, the Polish People’s Party represents the interests of the residents of towns and rural areas where it has yet entered into a fierce competition with the incumbent ruling party. Once it teamed up with the Kukiz’15 movement, the Polish People’s Party restored credibility in the eyes of conservative voters because the party led by Paweł Kukiz is widely known for its Euroscepticism and anti-migrant sentiments. The Confederation, for its part, has already fractured the right-wing, competing with Law and Justice in terms of a far-right political program: it puts forward nationalist views, is the only one of all Poland’s political groups to see the country outside the European Union and promotes anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim sentiments. The party is at the same time shares its pro-Russian sympathies while denouncing the incumbent government’s social wealth policies.

To sum up, five committees –– and a member of the German minority –– have passed the minimum threshold of votes to enter the Sejm. The United won 235 seats, Civic Coalition – 134, the Left – 49, Polish People’s Party/the Kukiz’15 movement – 30, and Confederation – 11.

The election campaign stirred up profound emotions while causing a severe rift among right-wing and left-liberal political groupings. Among those who, in addition to Law and Justice, emerged victorious from this polarization were both the Left and the Confederation, though on two sides of the political stage, taking most extreme stances on ideological matters. Law and Justice and the Civic Coalition remained far more moderate in their views. Speaking of the latter, it saw intra-party splits developing over these issues, as the party’s election list included the names of some conservative lawmakers that in the past held links to Law and Justice. Although in its rhetoric layer the PiS party firmly combatted the offensive of left-wing political groupings, as far as the practical, or legislative, dimension is concerned, it was in favor of maintaining the status quo, also by giving a red light to the party’s idea of tightening the country’s abortion law. The Confederation, for its part, took advantage of the state of affairs, demanding that the existing legal exceptions in the country’s 1993 abortion compromise bill be restrained. Under Poland’s current legislation, women can only get an abortion in cases of rape or incest, when the pregnancy poses a serious threat to a woman’s health, or when there is a severe foetal abnormality.

Electoral polarization pushed many young Poles towards the Left or the Confederation. Although many people aged 18–29 voted for the PiS party in quantitative terms, albeit if judging by this group’s percentage share in the final results of some parties, one can notice that both the Left and the Confederation successfully appealed to most of the youth. It is a safe bet to say that the Confederation’s recent electoral sweep depended mainly on support from young people, of them as many as 50 percent. This should hardly come as a surprise; a poll found that 82 percent of young people express negative feelings towards immigrants[5], compared to 70 percent of the whole population of Poland. As for Poland’s youngest voters, they seem to pin their hopes for the future on either far-right or far-left political groupings, at least as far as political values are at stake.

Why is Law and Justice so popular?

What lies at heart of the success of Law and Justice goes beyond its being eligible for the next four-year term in office. The PiS party claimed victory despite coming under bitter and long-lasting attacks from the country’s opposition parties continuously since 2015 after they rose to power for the second time in history, while first being in office between 2005 and 2007. Poland’s conservative government faced at the same time harsh criticism from the biggest Western media outlets, chiefly those based in Western Europe.

While reflecting on the reasons behind all these denunciations, it is vital to examine at least three factors. First of all, Poland, the European Union and the United States have long been the arena of ideological dispute, or what some have branded as the war of civilizations. The disagreement over values involves a liberal approach on the one hand, and conservative viewpoints on the other. The PiS party cherishes Christian values, an attitude that is tantamount to both its support for families as well as an aversion to left-wing plans to loosen Poland’s abortion law and provide broader rights to sexual minorities. While serving its previous term in office, Law and Justice abstained from taking legislative actions aiming to stiffen the abortion law or restrict the rights of sexual minorities. As for these two issues, the incumbent ruling party respected consensus that had been reached by the country’s then leading political forces many years before Law and Justice rose to power.

Secondly, the EU Member States are getting increasingly involved in a row over the future of the bloc, a situation that also occurs within some EU nations. Law and Justice’s political agenda is marked by strong rhetoric against some EU-wide initiatives: loosening transatlantic ties and building the EU’s strategic autonomy toward the United States, an open European migration policy –– including a compulsory mechanism for refugee relocation. High on the EU agenda, albeit criticized by the PiS party, is also an ambitious climate policy; once adopted by Poland, a country that generates most of its electricity from coal, this would considerably increase costs while reducing competitiveness of many industries. The Polish government considers the EU’s monetary union a risky endeavor for the country’s economy, a reason behind its rejection of Poland’s accession to the eurozone. Poland’s EU peers, with Berlin and Paris at the helm, have adopted a distinct attitude towards the above matters, pushing the government in Warsaw into changing its stance. European policymakers have claimed that Poland had hindered both crisis-prevention mechanisms and the progress of European integration. Poland, for its part, has taken the position that the suggested solutions remain incompatible with its national interests while going against the will of the majority of society. This was the case for the country’s green light for a compulsory mechanism for refugee relocation and the adoption of the euro as a legal tender. The Polish government eyes its respecting of the will of the nation as being loyal to democratic principles, which translated into the incumbent ruling parties’ victory in the 2019 elections (earlier the United Right captured Poland’s biggest electoral share in the European Parliament vote).

Thirdly, the PiS party has put in place a judiciary reform in a bid to modify the system that remained unreformed since the communist era. This sparked an immediate outcry from Poland’s legal circles while drawing strident criticism at home and abroad, from opposition parties and European institutions. The government argued that the changes introduced as part of the reform do not differ from solutions already in place elsewhere. Furthermore, European treaties foresee the organization of the national justice system –– along with any amendments –– as a competence reserved exclusively to the Member States, and the Polish executive branch may not act in breach of EU laws. Also, the Polish government firmly says that the laws passed were compliant with the Polish constitution –– a view somewhat chided by the country’s opposition forces that have yet failed to go up the legal path by not lodging a complaint to the Polish Constitutional Tribunal. In the light of Polish law, it is the sole institution eligible to determine whether the constitution has been breached.

Due to the three issues named above, Poland’s United Right government has become the object of scorn both at home and abroad. Among those that critically viewed Poland’s recent changes were other European policymakers, EU officials and most liberal media outlets. Nonetheless, despite adverse circumstances, the country’s conservative government claimed victory in the latest parliamentary vote. Why?

The party’s recent triumph stems from its adherence to its voters’ preferences in pursuing its domestic and foreign policies, and its fulfillment of election promises. If the majority of society refuses to adopt the single currency, it was a bothersome task to bow to pressure from German lawmakers who repeatedly encourage their Polish peers to join the monetary union. The same is true for the migration to the European Union from non-member countries, with 70 percent of Poles saying no[6]. 66 percent of respondents hold negative views of Muslims and are against their residing in the country. Most Poles speak out in favor of conservative values in the social sphere. While left-wing and liberal political groupings have unleashed a blistering attack on these qualities –– by seeking on the one hand to raise the rights of sexual minorities and insulting most Poles who hold more conservative views on the other (e.g. by profaning religious symbols) –– the government firmly defends the existing status quo and legal solutions passed in compliance with the Polish constitution. In this manner, Polish decision-makers drew widespread support from those who sought changes in the areas discussed above.

The Law and Justice government shows a conservative attitude to ideological matters while pursuing a left-wing social policy. The latter pushed the incumbents towards launching a social redistribution program –– developed with the country’s most economically vulnerable in mind –– that to no small extent backs families with many children who enjoy the 500 Plus child benefit package. By handing out 500 zlotys for every child in a family, the PiS government sought to reduce income inequalities that have been worsening since the time of Poland’s transition to democracy and the launch of European integration mechanisms. It counteracted a common belief that a narrow elite club benefitted from Poland’s democratic changes and integration with the bloc, though to the detriment of a large group of Polish citizens. Thanks to the PiS’ social redistribution agenda, this stereotype may gradually slide into oblivion while the fruits of Poland’s political shuffles, among which the country’s EU membership, should offer more balanced benefits for society. It is not without significance that in its previous term in office, the government maintained the high economic growth, equivalent to 5 percent of Poland’s GDP as of 2018, allowing the government to bankroll social expenditures.

All in all, the Law and Justice’s election triumph relies on three main pillars. First, the party enjoys relatively high credibility among its voters due to its urge to keep promises and respecting the society’s will being high on the agenda. This seems to be a principal element of a healthy democracy. Secondly, the government’s success stems from a list of mistakes made by opposition parties that shifted the campaign onto the ideological ground instead of presenting an account of complex reforms put in place by the ruling team. Hence, it turned out that the majority of voters are inclined towards the government’s conservative approach while rebuking radical social shifts hinted by the opposition. Political experts say that one significant factor has been the opposition’s lack of effective leadership and unsuccessful campaign that revealed many contradictions and inconsistencies in its electoral program. Perhaps this was except for a shared demand to remove Law and Justice from power, a statement that eventually proved insufficient for Polish voters. The success of Law and Justice derives from its social redistribution programs, though seen as one of many reasons underlying its triumph. Poland’s government groups have introduced a set of changes in the areas that earlier had been rebuffed by their political predecessors, varying from the adequately designed social redistribution programs to the judicial reform. In both cases, most voters approved these shifts, though they had come under harsh criticism from opposition politicians who branded them as populist (Family 500+ child benefit program) or judged noncompliant with the constitution (judiciary reform).

The festival of democracy

Poland’s 2019 general election is a success of Polish democracy, which is chiefly owing to a high voter turnout, being at its highest since the country’s transition to democracy in 1989, though slightly lower than during the 1995 presidential run-off. This autumn, some 62 percent of eligible voters cast their votes, which marked a 10-percent increase compared to the 2015 general election. Given the high voter turnout and the opposition’s victory in the Senate, it is challenging to depict Poland as plunged in a crisis of democracy. The 2019 general election has proven that the opposition is able to restrain somehow the Law and Justice’s grip on power. The two parties to the dispute –– both the incumbent government and opposition parties –– successfully mobilized their respective electorates in a bid to boost voter turnout.

The good condition of Polish democracy is also exemplified by a set of other arguments, especially when compared to the other EU Member States. A new Pew Research Center survey revealed that Polish society happily embraces the way multiparty democracy is working in the country, a finding that distinguishes Poland among its Central European peers. As many as 85 percent of Poles support the shifts to a democratic system, which is more than the percentage of Polish citizens backing their country’s EU membership as found in the same survey[7]. In Poland, 66 percent of respondents are satisfied with the way democracy is working. This shows a favorable result in comparison to many EU Member States, including France, Spain, Italy, Greece, and the United Kingdom, where most respondents said they are dissatisfied. Compared to a 2009 survey, thus when Civic Platform held power in the country, the percentage of people content with the way democracy was working rose by 13 percent. Also, 65 percent of Poles say the overall direction of the country is positive. This is far more than what Western European countries believe, with pessimistic moods being prevalent in France (65 percent), Italy (72 percent) and Greece (82 percent).

Some 71 percent of Polish voters are more likely than their European peers to believe that voting can give a say in what happens in their country –– more than in France or Germany. In comparison to Poland’s early days of transition to democracy, 30 percent more of Poles believe they are powerful enough to introduce changes in the country. This is also 24 percent higher than when Civic Platform was in power. It is challenging not to make a link between the country’s better results and a greater credibility of the Law and Justice government, which relates to its honoring of pre-election promises. These results, eyed as a remarkable success of Polish democracy, are best evidenced when compared to France’s attitude, where the perceived importance of regular elections has decreased by 10 percent over the past thirty years.

Most Poles believe that their state advances the interests of all citizens and not those of just a handful of the privileged. Positive views in this respect grew by 16 percent in comparison to the time when Civic Platform held power in the country. This may be a result of the expansion of social welfare programs pushed forward by the Law and Justice government. Nevertheless, citizen satisfaction allows for a fresh political mandate and boost voters’ faith in democratic principles. Trust in one’s own government as institution acting for the benefit of the whole society is higher in Poland than in Germany or France, for example.

In Poland, satisfaction with democracy translates into society’s contentment with European integration. In this respect, Poles score higher than Western European nations in Greece, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Where does Polish enthusiasm for integration come from? This seems to derive first and foremost from the way national democracy is working. Voters tend to get what they expect from the government, while the latter protects them against any adverse consequences of integration. Among them, most Poles see illegal immigration from outside Europe and their country’s joining the monetary union. Owing to the attitude adopted by their own government, Poles –– unlike other European nations –– do not feel repercussions of the migrant crisis and that in the eurozone, which shows their greater pro-European attitudes than those in Italy, Greece or France.

What European policy will the Polish government opt for?

Presumably, the incumbent government will not step off the path of its European policy as most voters have not changed their preferences. Poles are generally unwilling to see immigrants arriving in their country from outside the European Union and are fearful of risks related to the adoption of the euro. The government’s stance on these plans may eventually stiffen in the aftermath of the latest general election because there emerged in the Sejm a group of politicians that endorse radical Eurosceptic and anti-immigration beliefs. The Law and Justice government is likely to remain reticent towards plans to centralize power in Brussels, viewing it as an attempt to strip the EU Member States and national voters of their competences. This could loosen Poland’s national democracy, especially the sense of responsibility Poles have for what happens in their country.

Poland will probably make efforts to expand European Treaty freedoms in the domestic market, especially as far as services are concerned. Also, the government in Warsaw will seek to enhance transatlantic bonds while sustaining NATO’s predominant status in the area of European security. Furthermore, the Law and Justice government is likely to uphold its current cooperation within the Visegrad Group in European policy-making. Poland’s support for EU-wide climate policy will remain reliant on how generously the European budget can cover the expenses of the country’s energy transformation. Deprived of such help, Poland could bear the brunt of the mounting costs of Europe’s arduous climate policy, and no democratic government can accept such a state of affairs. Some time ahead of the general election, the Polish government had announced the urge to follow up the judiciary reform, a move that might reignite spats with Brussels.

Conclusions

Poland’s election results reflect first and foremost a triumph of democracy, seen to a way lesser extent as the victory of a given political party. This success relies primarily on the fact that voters have a sense of their needs being communicated to policymakers and that voting affords them some influence on what will happen next. Nevertheless, the negative facet of Polish democracy is excessive polarization and mounting support for the country’s extreme political groups on both sides. It is noteworthy that –– like in Poland –– there is an intense political polarization in many other EU Member States. Moreover, European integration is itself branded as conducive for glaring discrepancies and intense election emotions. In present-day Europe, many electoral disputes refer to what values should prevail across the bloc, along with to what extent the EU institutions are entitled to interfere in the internal affairs of Member States, and how Brussels should respond to the ensuing European crises. Naturally, extreme and anti-European attitudes pose a threat to integration mechanisms. However, the way of tackling these challenges should be far from narrowing down national democracy or impose censorship on any policymakers that promote anti-European or even Eurosceptic viewpoints. The salvation for the European Union may be higher EU decision-makers’ respect for voters across the Member States while allowing citizens throughout the bloc to restore faith in their own national democracies. Europe can stay strong if its national communities and democratic procedures are so. Also, the progress of European integration depends on mutual respect that European policymakers accord to national voters and their characteristics. Besides, any endeavors to push forward proposals against the will of both national voters and democratically elected governments are the worst solution of all. Consequently, any actions taken to bolster flexibility –– rather than appointing centralized authorities –– should open up an opportunity to pause disintegration processes within the bloc.

Author:

Prof. Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse – a sociologist, political scientist and historian. He is a professor at the University of Warsaw. Head of Department of European Union Policies at the Institute of European Studies. He specializes in the analysis of economic policies in the EU and the Member States, as well as in public management, geo-economics, Europeanisation, EU theoretical thoughts.

[1] The United Right coalition is a right-wing alliance formed between Law and Justice, United Poland, and Poland Together.

[2] Data from the Polish National Electoral Commission: https://pkw.gov.pl/853_Wybory_do_Sejmu_i_Senatu_w_2019_r [access: 10/27/2019].

[3] The biggest opposition bloc is an alliance formed between Civic Platform, Modern, The Greens, Polish Initiative, Silesian Regional Party, Social Democracy of Poland, and Freedom and Equality.

[4] The Left is a parliamentary coalition made out of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), Spring and Together.

[5] “Świat Młodych 5”, IQS, Warsaw 2018.

[6] Stosunek Polaków I Czechów do przyjmowania uchodźców [Poles and Czechs’ attitude to receiving refugees], CBOS, 87/2018.

[7] European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism, Pew Research Center, Washington, DC, October 15, 2019.

the United Right earned 235 seats, Civic Coalition – 134, the Left – 49, Polish People’s Party/the Kukiz’15 movement – 30, Confederation – 11.

The party’s recent triumph stems from its attempts to adhere to its voters’ preferences while pursuing domestic and foreign policies and to keep election promises.

The publication of the Special Report was co-financed from the funds of the Civic Initiatives Fund Program 2018.

The concept of analytical material was created thanks to co-financing from the Civil Society Organisations Development Programme 2019.

Selected activities of our institution are supported in cooperation with The National Freedom Institute – Centre for Civil Society Development.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.