THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 5 July 2019 Author: Joanna Żelazko

The Katyn Massacre – the Way to the Truth

‘The Katyn Massacre’ is a symbolic term. It refers to a series of mass murders of Poles imprisoned in special camps of Kozelsk, Starobilsk, and Ostashkov, and in prisons located in the so-called Western Ukraine and Western Belarus (Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic that were incorporated into the USSR after the Soviet invasion of Poland on September 17, 1939). This term has been widely adopted as the first place discovered regarding this tragic set of events was located in the Katyn Forest and, for a long time, it remained the only one that was known.

KATYŃ, RUSSIA, APRIL 8, 2017. POLISH WAR CEMETERY IN THE FIELD OF THE STATE MEMORIAL COMPLEX “KATYN”. © TOMASZ GZELL (PAP)

KATYŃ, RUSSIA, APRIL 8, 2017. POLISH WAR CEMETERY IN THE FIELD OF THE STATE MEMORIAL COMPLEX “KATYN”. © TOMASZ GZELL (PAP)On August 23, 1939, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the Foreign Minister of Nazi Germany Joachim von Ribbentrop signed a neutrality pact in Moscow. The secret part consisted of a protocol under which the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, 1939 – only two weeks after Nazi Germany had attacked its eastern neighbor. Approximately 250,000 Poles were taken prisoner on the Soviet-occupied territory. Among them included nearly 15,000 Polish officers, police and gendarmerie, prison guards and soldiers of the Border Protection Corps; all were placed in three special prison camps at Kozelsk, Starobilsk, and Ostashkov under the supervision of the USSR NKVD Prisoners-of-War Administration.

Polish prisoners-of-war were interrogated by NKVD officers. The Soviets intended to find out about their political views, their potential will to collaborate with the authorities of the USSR as well as the possibility to use prisoners of war (POWs) for any propaganda activities. Meanwhile, as the chief of the NKVD Lavrentiy Beria considered most of the prisoners to be an “unpromising counterrevolutionary element” and “hardened, incorrigible enemies of the Soviet power,” he submitted a special request to the ACP (b) Politburo to shoot them without any trial. According to Beria’s demand, Polish civil detainees from prisons in Ukraine and Belarus would also be executed. The mass shooting would take place neither “without summoning arrested persons nor without presenting any charges or decisions to terminate the investigation and indictment.” The decision dated March 5, 1940, was accepted by the signatures of Joseph Stalin, Kliment Voroshilov, Vyacheslav Molotov, and Anastasia Mikoyan. Besides, the document contained an annotation that the proposal had also been supported by Mikhail Kalinin and Lazar Kaganovich.

The transport of Poles from “special prison camps” (in the Soviet documentation, this was referred to as “camps unloading”) began on April 3, 1940, from Kozelsk, a day later from Ostashkov and on April 5 from Starobilsk. Mass executions were carried out by officers of the NKVD field units.

The prisoners from the Kozelsk camp were divided into groups of 100 to 300 and then taken by rail to the Gniezdowo station near Smolensk and from thereby prisoner transport vehicles to the forest near the village of Katyn. Some of them were killed in a villa in the forest; it was from there that the bodies were transported to the burial pits. Other victims were led one by one, with their hands tied, towards the end of the trench where they were shot dead. In total, no less than 4,410 prisoners from the Kozelsk camp were executed while only 178 managed to survive.

Prisoners of war from the largest of the three camps in Ostashkov, reserved for officers of police and military gendarmerie, were transported to the internal prison of the NKVD headquarters in Kalinin (now Tver). They were murdered in this building, in a specially adapted prison cell. The bodies were then buried in the forest near the village of Mednoye. In total, 6,314 prisoners were killed while only 127 people survived.

MUSEUM OF THE 10TH PAVILION AT THE WARSAW CITADEL, APRIL 27, 2018, WARSAW. PHOTO PRESENTED DURING THE CEREMONY COMMEMORATING THE POLISH POWS OF THE SOVIET CAMPS IN KOZIELSK, OSTASHKOV, AND STAROBELSK ON THE 78TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE KATYŃ MASSACRE, TVER, AND KHARKOV © TOMASZ GZELL (PAP)

MUSEUM OF THE 10TH PAVILION AT THE WARSAW CITADEL, APRIL 27, 2018, WARSAW. PHOTO PRESENTED DURING THE CEREMONY COMMEMORATING THE POLISH POWS OF THE SOVIET CAMPS IN KOZIELSK, OSTASHKOV, AND STAROBELSK ON THE 78TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE KATYŃ MASSACRE, TVER, AND KHARKOV © TOMASZ GZELL (PAP)The captives from Starobilsk were sent by rail to Kharkiv and placed in an internal NKVD prison where they were shot. Their corpses were then transported by trucks and buried in the forest area near the village of Pyatikhatka (today located within the boundaries of the city of Kharkiv). In total, 3739 prisoners from Starobilsk were killed, while only 90 survived.

The Soviet authorities sentenced to death approximately 3,000 Poles detained in prisons in Ukraine; meanwhile, 3000 were incarcerated in various penitentiaries in Belarus as well over 1,000 from the Bialystok region – a total of over 7,000 people. In the 1990s, mass graves were discovered in the villages of Bykovnia near Kyiv (Ukraine) and Kuropaty located in the vicinity of Minsk (Belarus).

Out of all the prisoners kept in the “special prison camps,” only 395 survived; they were taken to the Pavlischev-Bor camp and then to Griazovets in Vologod oblast. The survivors thought that their colleagues were kept in similar camps in other locations. Nonetheless, after the deportation, the prisoners disappeared “without a trace” while their families, desperately seeking any information about their loved ones, were provided with false answers.

Finally, it became possible to search for “missing persons” thanks to a Polish-Soviet military agreement signed on August 14, 1941. On this basis, the Polish Army was formed in the USSR; it embraced Polish officers who were granted freedom under the decree on amnesty issued only two days earlier by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. The Army, formed under the directions of General Wladyslaw Anders, consisted of Polish citizens who had been hitherto incarcerated in prisons, labor camps and places of exile on the territory on the USSR. On the order of General Anders, a special office of the Staff of the Polish Army was created to search for missing persons; also, the institution, governed by Captain Jozef Czapski, was charged with collecting any information about sought officers.

Representatives of the Polish authorities also attempted direct interventions in Moscow. The then Polish Ambassador to the USSR, Professor Stanislaw Kot, discussed the issue of the missing prisoners with Andrey Vyshinsky, a Soviet deputy commissar of foreign affairs. Moreover, a special note regarding the fate of the officers was sent to the Soviet authorities by the then Polish Prime Minister Wladyslaw Sikorski. However, it remained unanswered. In addition, Sikorski did not receive any information during his conversation with Joseph Stalin that took place on December 3, 1941, in Moscow.

The possibilities of explaining the situation did not improve over time and were even hampered by the growing tension in Polish-Soviet relations. The latter was caused by factors such as the deteriorating living conditions of the Polish Army in the USSR and Stalin’s pressure to send the Polish troops to the Eastern Front, which ultimately led to the evacuation of soldiers and their families to Iran in 1942.

On April 13, 1943, the German authorities issued an official announcement via Berlin radio about the discovery of mass graves of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest. Two days earlier, the Transocean Agency had informed about the uncovering of a mass grave “with the corpses of 3,000 Polish officers.” It was only on April 15, 1943, that the Soviet newspaper Pravda, as well as Moscow radio, depicted their theory about the death of the Poles. The Soviet side declared that after Nazi Germany had invaded the USSR, the Germans executed prisoners of war who were located in camps near the city of Smolensk. Such statement began a half-century-long dispute over the presentation of the exact course of the crime, and indeed the guilty party thereof.

The Germans had been aware of the burial site of the executed Polish prisoners almost a year before it was announced to the general public. In the summer of 1942, a group of Polish workers from the German organization Todt, who were forced to build military facilities near Katyn, learned about the graves of Polish soldiers from the local population. Once the credibility of this information had been checked, they put two birch crosses where the site was indicated and informed their superiors; however, the German authorities were not interested in this at that time. It re-emerged only at the turn of January and February 1943 when the Germans ordered that part of the area be dug out and, as a result, the burial sites were discovered. The local population was then questioned, and the information provided was then passed to General Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command. However, it was only after one month that the Germans decided to open the graves, and they did so purely for pragmatic reasons. After the German defeat at Stalingrad, the state propagandists aimed to use the information about the crime committed by the Soviets on Polish officers to disrupt the Allies. As such, bringing about a possible dispute between the governments of Poland and the Soviet Union was seen as having the potential to cause a severe split within the entire coalition. Such a conflict may have resulted in decisions about certain activities to be carried out on the fronts, and thus, it might have improved Nazi chances in their fight against the anti-Hitler coalition forces.

A vital element of the propaganda campaign was the conviction of Poles, including those living in the German-occupied areas, and that it was the NKVD that had committed crimes in the Katyn Forest. For this reason, the Germans sent to Katyn delegations of Poles from occupied territories. Among them were doctors, representatives of the Polish Red Cross and the Caritas charity organization; the Germans aimed to show them the exhumation works carried out as well as to convince them about the authenticity of the graves. The German Commission worked under the supervision of Professor Colonel Gerhard Buhtz. Moreover, the Germans delegated to Katyn a group of Polish officers from the Oflag II-C Woldenburg as well as prisoners of war and journalists from other countries, including the United States.

At the end of April 1943, a group of experts in forensic medicine and criminology came to Katyn from 12 satellite countries or allied countries as well as those occupied by the Third Reich. For two days, their members carried out any necessary works in the forest near Smolensk. The scientists unanimously stated in the final protocol that the mass executions had taken place in 1940, during the period when the Smolensk region remained under Soviet rule.

The German press published frequent reports on the exhumation works: for instance, the number of victims was estimated at 10,000-12,000, even though not all graves could be discovered. Such estimates, however, allowed the remaining prisoners from special camps to be “found” to show the grander scale of murder committed. Blame for the Katyn Massacre was put on the NKVD. At the beginning of June 1943, works in Katyn were interrupted. According to the Germans, such decision was made due to the approaching front; moreover, they had no intention to expose people conducting exhumation works that may potentially increase the risk of epidemics. Even if the arguments mentioned above were true, they served primarily as an excuse to put the undertaking to an end; at this stage of the exhumation, it was certain that the number of bodies buried in the Smolensk forest, which had been announced in all relevant statements, could not be confirmed. Thus, doubts could arise as to whether Germany had correctly blamed the Soviet Union for committing the mass genocide. Experts responsible for leading the works deliberately decided not to dig up the last grave; instead, they claimed that it contained the remains of other victims. Lists of names identified during the exhumation of the victims were printed in the Polish-language press in the occupied country. Prepared in a hurry and with little accuracy, they tended to contain names of people who had not died in Katyn; such mistakes additionally undermined the credibility of German sources.

Due to the fact that both the Germans and the Soviets accused each other of having committed the mass executions in Katyn, on April 17, 1943, the Polish government wrote an official request to the International Red Cross Committee to send to Katyn a special delegation whose representatives would be in charge of verifying the incoming information. Having discovered the intention of the Polish authorities, the Germans submitted their demand only two days later; thus, they managed to create the appearance of Polish-German cooperation on the issue of the Katyn Massacre. The International Red Cross was even ready to deploy a special commission to the crime scene, but such a decision had to be accepted by all parties concerned. The authorities of the USSR did not give their consent for fear of an impartial and unquestionable verdict. So, the Commission did not make it to the Katyn Forest. The Soviets took advantage of this situation to accuse the Poles of collaborating with Germany. In addition, they broke off diplomatic relations with the Polish government in London on the night of April 25-26, 1943. It was a convenient excuse for Stalin who was able to officially announce his support for Polish communists in the Soviet Union.

All materials collected during the German exhumation were then transported to Cracow where they were examined by a group of employees of the Institute of Forensic Medicine and Criminalistics under the supervision of Dr. Jan Robel (the documents collected are often referred to as the “Robel archive”). Original documents were taken by the Germans when they retreated in 1945. It is possible that the files burned during the bombing carried out by Allied Air Forces near the village Redebeul in the vicinity of Dresden. However, the Poles managed to make illegal copies, thanks to which at least two sets could remain in occupied Poland. One of these copies was hidden in the headquarters of the Polish Red Cross in Warsaw. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in a fire when the Germans demolished the city after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising in the autumn of 1944. The second one was placed in the Department of Chemistry of the National Institute of Forensic Medicine and Criminalistics in Cracow and had not been discovered until 1991 when it was found during renovation works.

On September 25, 1943, the Soviet Army occupied Smolensk. Its next step was to establish a “Special Commission for Determining and Investigating the Circumstances of the Execution of Prisoners of War – Polish Officers – by Fascist Nazi Invaders in the Katyn Forest.” As the name suggests, it had already recognized German guilt even before it proceeded to examine the evidence. The works led by Nikolai Burdenko were concluded with the publication of a report on January 24, 1944. In the document, Soviet experts in forensic medicine deduced based on examination of the exhumed corpses that the execution had taken place between September and December 1941, as evidenced by newspapers and letters found on the bodies. The number of victims was estimated at 11,000. Thanks to such a conclusion, it was possible to include the majority of missing prisoners as well as to close the issue of the need for any further exploration. According to the Commission, Polish prisoners were responsible for constructing roads in the Smolensk area; this is also where they fell into the hands of German officers and were then later shot by them. The Polish communists confirmed the Soviet version.

After the end of the Second World War, it may have been possible to identify the perpetrators during the trial of the Nazi leaders at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. The indictment, brought by the Soviet prosecutor, contained among other things the allegation of committing mass executions of Polish officers in Katyn. In the period of July 1-3, 1946, the judges got acquainted with the evidence and questioned the witnesses. The only proof presented by the Soviet prosecutor’s office was a report prepared by the Burdenko-led Commission. The Court agreed to hear three witnesses of each party, that is, the Germans and the Soviets; no Polish witnesses were included in this group. The Tribunal did not refer to material evidence possessed by the Polish diaspora, either.

Among the testimonies examined was that of Docent Marko A. Markov from Bulgaria, a member of the German Katyn Commission in 1943. After the end of the war, he was accused of cooperating with Germany by the Supreme Military Tribunal of Bulgaria. In addition, Markov, as a “foe of the people,” spent several months in prison. Once he had regained his freedom, he suddenly changed all his declarations. During one of the Nuremberg trials, he stated that back in 1943, he had been forced to sign a German document and that the Germans could be blamed for the mass executions of Polish people. Such a change in attitude was probably the price for his freedom.

A completely different approach was adopted by Professor François Naville, an expert in forensic medicine at the University of Geneva and Professor Arno Saxén, a specialist in pathological anatomy at the University of Helsinki. Both scientists upheld their conviction about the guilt of the Soviets. German Colonel Friedrich Ahrens, who was accused by the Soviets of committing the Katyn slaughter along with the 537th Communication Regiment, volunteered to provide testimony in Court. Nonetheless, it turned out that there had been no evidence to maintain such accusation.

Even if investigators discovered in trenches many shells from German-produced ammunition, the research on their markings (symbols) indicated that they had been produced in the interwar period; at that time, the USSR imported a lot of weapons and ammunition from Germany in the framework of military cooperation between both countries. Some of the murdered prisoners-of-war were additionally hit with bayonets. During the trial, information that their characteristic traces, which could have made it possible to indicate the guilty, was not used – the bayonets were quadrangular, like the ones used by the Soviets, and not flat like a knife, which describes the bayonets used by German soldiers.

In its judgment rendered on September 30 – October 1, 1946, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg did not recognize the guilt of the Germans in the Katyn Massacre; the judges did not indicate any guilty entities, either. Instead, they decided not to mention the crime in the conclusion of the final opinion. Due to the political situation then, it was more convenient not to address the issue at all.

Poles living outside their motherland widely discussed the Katyn Massacre. The so-called Katyn literature, which concerned prisoners from all three special prison camps, embraced both memoirs of Władysław Anders, Jozef Czapski, Stanisław Swianiewicz or Bronisław Mlynarski, but also scientific monographs such as the one written by Janusz Zawodny. Thanks to them, it was possible to spread the truth about the slaughter around the world.

Due to some changes in the global political situation as well as increasing tension between the Soviet Union and the United States, in 1949, the establishment of the American Commission for the Investigation of the Katyn Massacre headed by Arthur Bliss-Lane, a former US ambassador to Poland, was made possible. The Commission was primarily in charge of collecting German publications dating back from the Second World War; moreover, its members managed to obtain materials held by the Polish diaspora in London. However, it did not have the opportunity to examine any other documents.

In September 1950, a report written by Colonel John van Vliet who was taken by the Germans to Katyn along with a group of British and American prisoners of war was released and later published. In 1945, he wrote a report on Katyn confirming the version about Soviet guilt. Nonetheless, his files were later made secret. On September 1951, a group of US congressmen, impressed by the memo, created a special US congressional committee to investigate Katyn. A year later, the committee released a report prepared based on information gathered during the hearing as well as some other official documents. In its conclusion, American officials wrote as follows: “We unanimously agreed that there was no issue or reasonable doubt as to the fact that the NKVD of the Soviet Union had mass murdered Polish officers and members of the intelligentsia in the Katyn forest near Smolensk.” However, the committee’s final opinions did not align with Poland’s official standpoint in this respect. The country’s censorship body made its best efforts to present them as “imperialist lies.”

Many years later, on January 1, 1972, the British authorities decided to reveal reports written in 1940 by a British Ambassador to the Polish government-in-exile in London, Owen O’Malley, whose memos were initially addressed to the British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden. He pointed to Soviet guilt. In 1943, despite the lack of doubt in this matter, Eden regretted the fate of Polish officers: “but even if they were not alive”, he said, “no action from the Polish government could raise them from the dead while it may constitute a risk to British interests in the eyes of the Russians.” Due to political reasons, the truth about the guilty party remained top secret.

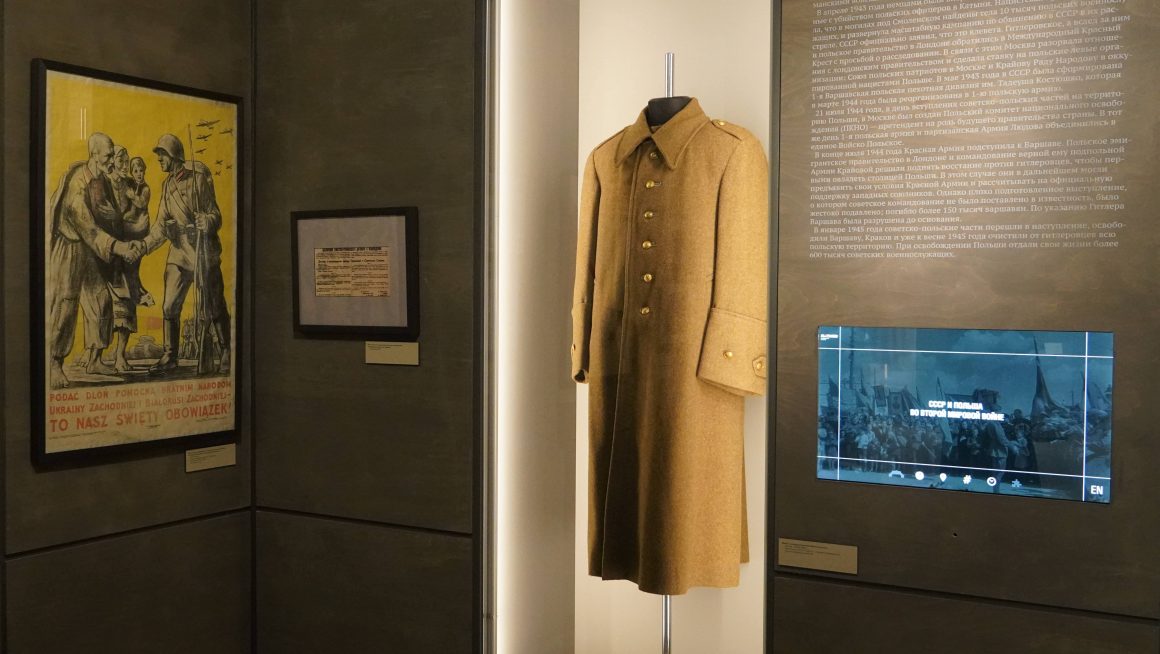

KATYŃ, RUSSIA, APRIL 20, 2018. OPENING OF THE REBUILT MEMORIAL IN KATYŃ, INCLUDING A NEW MUSEUM CENTER, WHERE AN EXHIBITION ON RUSSIAN-POLISH RELATIONS CAN BE FOUND. © WIKTOR MALAK (PAP)

KATYŃ, RUSSIA, APRIL 20, 2018. OPENING OF THE REBUILT MEMORIAL IN KATYŃ, INCLUDING A NEW MUSEUM CENTER, WHERE AN EXHIBITION ON RUSSIAN-POLISH RELATIONS CAN BE FOUND. © WIKTOR MALAK (PAP)Poland, which was in the Soviet zone of influence, officially recognized German guilt in the Katyn Massacre. Nonetheless, despite communist propaganda, many people knew the truth about the slaughter and were prepared to be penalized for spreading the facts to the public. It seems that the first post-war decade was particularly repressive in this respect. Despite an inevitable “thaw” that took place after Stalin’s death and settlements caused by Nikita Khrushchev’s secret speech “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of Soviet Russia in 1956, the truth about Soviet guilt was however not disclosed. If such information had been unveiled, it would have been necessary to reveal any documentation regarding the crime, to identify all personal details of its perpetrators as well as to admit that Stalin had decided to murder prisoners of war (protected by international law). The 20th Congress took place only two days after the US Committee had announced that the Soviets were to blame for the Katyn Massacre. In this situation, especially in the period of the ongoing “Cold War,” such a step would provide enemies with additional arguments.

The Soviets aimed to distract attention away from the real crime scene; in order to do so, they attracted public attention to the village of Khatyn, located 250 kilometers east of Katyn, whose population was massacred by the Germans. In 1969, the slaughter was commemorated in a memorial that was later visited by US President Richard Nixon during his visit to the Soviet Union in May 1972. The names of Katyn and Khatyn, although phonetically similar for many foreigners, might have appeared credible for Soviet attempts at mystification.

The Katyn Massacre had not been discussed in Poland until the turn of the 1970s and 1980s when many Poles became interested in the tragic case. Of course, such interest was personal. However, some authors published books (most often unauthorized reprints of texts that had earlier appeared in the West as underground publications), including Dzieje sprawy Katynia [Katyn 1940] by Jerzy Łojek (under the pseudonym of Leopold Jerzewski) and Dramat katyński [The Katyn Drama] by Czesław Madajczyk. Many Poles sought to manifest their attitude towards the Katyn executions by lighting candles on their windowsills on April 13 and donating money for memorial plaques in churches. On July 31, 1981, thanks to the efforts of the Katyn Committee, a monument in honor of the victims was unveiled at the Powazki Cemetery in Warsaw.

Nonetheless, it was “robbed by unidentified persons” on the same night. However, the authorities of the Polish People’s Republic could not accept such a blatant expression of opinion. On April 4, 1979, the Katyn Institute in Cracow started its operations, even despite possible repressions from the part of the country’s security services. Illegal at first, it only gathered a small group of people, to begin with.

Due to the dynamic political situation, the anti-government opposition in Poland, which was gaining more and more importance in the country, forced the authorities to make political concessions as well as to liberalize the living conditions of its citizens. As a result of perestroika, introduced in the Soviet Union on April 21, 1987, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev and First Secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party Wojciech Jaruzelski signed a declaration that gave birth to a committee of Polish and Soviet party historians. It was supposed to explain the problems of the shared history of both countries. Due to the immense public interest, priority was given to the Katyn Massacre. Nevertheless, the Soviet part of the Commission did not present any official information about the perpetrators; it falsely stated that there had been no sources to determine guilt. Polish investigators, based on their materials, managed to develop reports on Soviet responsibility for the massacre as well as they could in specifying that the executions of Polish prisoners of war from Kozelsk, Starobilsk and Ostashkov had begun on April 4, 1940.

Moreover, as the Katyn slaughter was no longer a “public secret” and Poles could openly speak about the tragedy, the relatives of victims began to establish the so-called Katyn Families Association. The first was officially registered in May 1989. Since 1990, at the initiative of the Independent Historical Committee of the Katyn Massacre, it was possible to issue “Katyn Booklets” (“Zeszyty Katynskie”).

Besides, there was a group of Russian historians and journalists who intended to conduct a careful investigation as well as carrying out independent research for further documents. The breakthrough came in 1990, when they were allowed to query the files of the Special Archive and in the Central State Archives of the Supreme Archives Board at the Council of Ministers of the USSR. In mid-March 1990, the Soviet press published a statement on the findings contained in Soviet documents by Natalia S. Lebedeva; the reports seemed to confirm that the NKVD had to be blamed for the Katyn Massacre. At the same time, it was upheld that the reluctance of the Soviet authorities impeded their “findings.”

On April 13, 1990 – today celebrated as World’s Day of Remembrance for Victims of Katyn Massacre – the TASS news agency in Moscow issued an official statement. According to the communiqué, the NKVD was responsible for slaughtering Polish officers in the spring of 1940. All personal blame was put on Lavrentiy Beria and Vsevolod Merkulov, which was a breakthrough event because the USSR authorities pleaded guilty to the Katyn Massacre for the first time in 50 years. It was on the same day that Mikhail Gorbachev handed over the first part of the documents on Polish prisoners-of-war to General Wojciech Jaruzelski. The public widely discussed the fact of its disclosure. However, little media attention was paid when Polish Consul General to Kyiv, Ryszard Polkowski, received more folders contained with documents. Despite the secret place of storage, it was possible to determine that they had been kept in the Central Archives of the Soviet State Army. More materials were delivered to President Lech Walesa on October 14, 1992. These included essential investigative material to explain the crime, namely Package no. 1 that included Beria’s order to slaughter Polish POWs, internees, and prisoners. Moreover, the files contained the minutes from the Politburo meeting, which took place on March 5, 1940, during which the request had been accepted followed by its immediate implementation.

Since the 1990s, Polish publishers have printed numerous books and articles on the executions of Polish prisoners of war incarcerated in special camps at Kozelsk, Starobilsk, and Ostashkov. They consist of monographs as well as scientific and popular articles, biographical notes of the victims, as well as analyzes and reprints of previously unknown documents. Based on materials taken from the Soviet archives, they sought to broaden the knowledge about the situation in the camps and the details of the executions. Moreover, information on the Katyn Massacre can also now be found on various websites.

In the spring of 1990, due to the insistence of the Polish authorities, the prosecutor’s offices in Kharkiv (Ukraine) and Tver (Russia) launched investigations aiming to establish the perpetrators of the slaughter of prisoners-of-war from the special camps. Out of thousands of witnesses questioned, the most important facts were delivered by Mitrofan Syromatnikov and Dmitry Tokarev. The former served as a senior caretaker of the internal block of the NKVD prison in the years 1939-1941 (his testimony concerned the execution of prisoners from the Starobielsk prison camp that took place in Kharkiv) while the latter was the head of the NKVD headquarters in Kalinin (now Tver). His statement referred to the prisoners based in the Ostashkov camp and contained the course of the crime as well as both organizational and technical details depicted with almost pedantic accuracy.

However, not all living witnesses were eager to testify in Court. Major Piotr Soprunenko, former NKVD director of POW affairs, claimed that he had heard about the Katyn Massacre on the occasion of the arrival of Polish President Wojciech Jaruzelski to Moscow in April 1990. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the investigation was continued by the Russian Prosecutor’s Office. However, it decided to discontinue the proceedings on September 21, 2004. No one has ever been officially charged in Court because the Russian Federation does not recognize the Katyn Massacre as genocide; instead, they perceive it in terms of a crime whose prosecution has already expired. Thus, on November 30, 2004, the Katyn Committee notified the Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation of a crime committed by the NKVD. As a result, Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance issued a decision to commence an investigation into the Katyn Massacre. The primary purpose of the proceedings was to determine the perpetrators of the crimes: those who issued orders as well as their direct executors.

Thus, since Russia did not recognize this crime as political murder, members of the Katyn Family filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. According to a judgment published on April 6, 2012, the Court ruled that the execution of Polish officers in Katyn could be perceived in terms of a war crime (which could not expire) while Russia humiliated the relatives of the killed by refusing to grant them the status of the victim. On the other hand, in the same ruling it was stated that the Court had no authority to assess the investigation from a formal point of view as it concerned events from 1940; at that time, the institution did not exist nor did the European Convention on Human Rights (it entered into force in 1953).

However, no judgment can change the view of ordinary residents of the Russian Federation. Moreover, even if the USSR admitted its guilt as well as despite archival documentation blaming the Soviets, some publications have recently attributed responsibility for the Katyn Massacre to the Germans as evidenced by the articles and books of Russian journalist Yuri Mukhin. At the same time, in Russia, there are currently many books and articles being published by such authors as Vladimir Abarinov, Andrey Guryanov, Natalia S. Lebedeva, Valentina Parsadanova and Oleg Zakirov who aim to present the truth about the Katyn Massacre.

Russian citizens, just like Germans after World War II had to confront the responsibility for the crimes committed by the Third Reich, will now have to accept that they are historical heirs of the “achievements” of Stalin’s regime. Thus, they are facing a difficult task; they must work out a formula that would reconcile this fact with the lack of direct personal responsibility of modern Russians for these acts of atrocity.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.