SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 14 September 2018

Caspian Summit: Consequences for the Region

- Five Caspian states – Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan – have adopted a convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea. The deal officially ended a 22-year-old impasse as all interested countries finally managed to reach a consensus. Nevertheless, the document has yet to be ratified and it does not fully resolve disputes over the division of the reservoir.

- The agreement provides for preventing non-Caspian countries from deploying their troops to the region; such conclusion translates into the lack of possibility to lease ports in order to establish foreign military bases. This provision appears beneficial both for Russia and Iran since the two countries are afraid of growing American influence in this area.

- Moreover, the deal allows for the implementation of underwater gas pipeline projects without any approval of all coastal states. Theoretically speaking, such provision may potentially open the way to the construction of the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline; nonetheless, it seems that the project has lost some of its significance over the last decade and it might be blocked on the pretext of environment consultations.

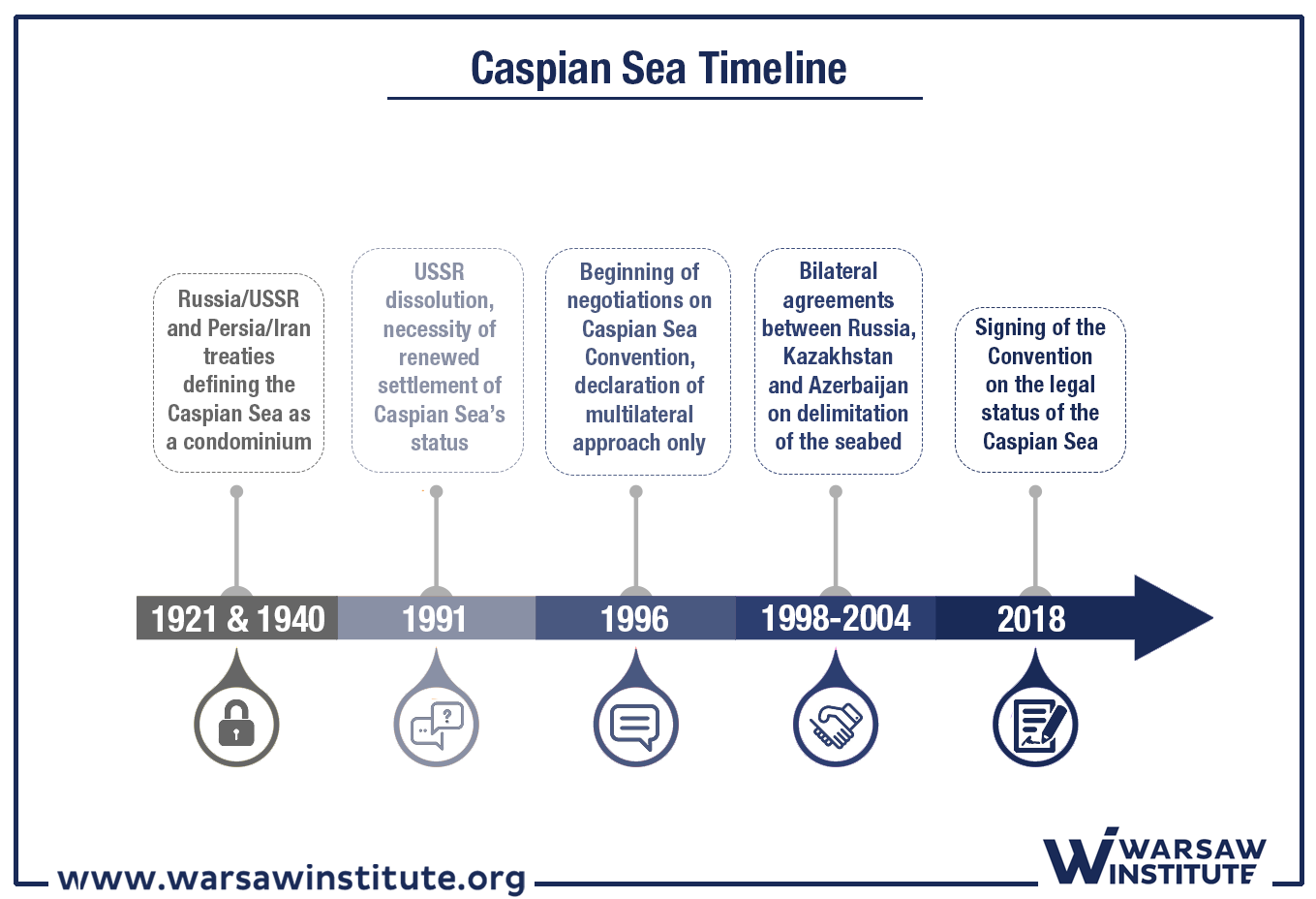

The leaders of five Caspian states met on August 12, 2018, in the Kazakh city of Aktau to sign a landmark deal on the legal status of the water region. Formally, works on the treaty has been in progress since 1996, when all interested states agreed to initiate their meetings in the five-sided format. The need to adopt appropriate regulations resulted mainly from the fact that – following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 – the reservoir ceased to be exclusively a Soviet-Iranian condominium while newly formed coastal states of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan sought to put forward their claims to the waters. Since that time, a number of issues related to the division of the Caspian Sea – including the right to exploit oil and gas resources as well as to construct pipelines – has remained the subject of dispute between some of the aforementioned countries.

The convention constitutes an attempt to regulate the Caspian Sea’ status as such as well as it aims to set out general directions of further works on its final division between five littoral Caspian nations. Moreover, the five states have adopted basic principles with regard to the use of both the body of water and the seabed, including shipping – which prevents non-Caspian countries from navigating on the reservoir – as well as fishing, conducting research, constructing infrastructure and exploiting raw material. As for the environment protection of the Caspian Sea, the new agreement refers to the principles that had been earlier formulated in the so-called Tehran Convention and its ancillary Protocols, including the Protocol on Environment Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context.

The convention on Caspian Sea’ legal status – similarly as the aforementioned Protocol– will need to be ratified by each of the five signatory states. Moreover, parties to the agreement have not specified any due date that would potentially reduce the time limit for ratification procedures. Thus, the provisions of the convention are not explicitly binding yet; they will be given legal effect only when the last of the five states finally approves the document.

Sharing the Resevoir

As for dividing up the Caspian Sea, the signatory states have adopted separate rules both on the water distribution – which entitles the countries to conduct fishing activity – as well as on the seabed, which enables the exploitation of natural resources and the construction of artificial infrastructure (such as pipelines). In the first case, each country shall retain sovereignty over territorial waters up to 15 nautical miles from their coastlines; in addition, all five states will have the exclusive right to fish an additional 10 nautical miles. The most part of the reservoir will be referred to as the common maritime space . More details on the zone limits will be included in further agreements.

In addition, the five littoral states have made some preliminary arrangements on the division of the Caspian Sea seabed and its natural resources. According to the convention, the delimitation is to take place due to further bilateral agreements between interested countries. Moreover, the parties to the deal have vaguely treated the way of dividing the seabed, according to which the sector delimitation should take place with regard to “generally recognized principles and norms of international law.” As a result, the fact of adopting the convention will not be decisive for resolving any territorial disputes between Iran, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan (see map below); the three countries will now have to agree upon the establishment of potential boundaries of their common sectors.

Thus, it seems that the most difficult task will be to reach a consensus on the southern part of the Caspian Sea: Kazakhstan, Russia and Azerbaijan do not put forward any specific territorial claims; however, it is not the case of Iran as the state may potentially get the smallest part of the seabed that limits its territory to a restricted area adjacent to the coast. Such state of matters is possible because the aforementioned “generally recognized principles and norms of the international law” specify that the surface of the sectors depends on both length and shape of the coast – for instance, according to the equidistance principle, Iran would be granted only 13-14 percent of the reservoir.

Iran has hitherto advocated either an even division of the Caspian Sea into 20-percent sectors or a joint exploitation of natural resources from the seabed. As a result, some Iranians have considered the convention in terms of a state’s betrayal; the issue was commented on by Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif who expressed his uttermost confidence that negotiations with neighboring countries would make it possible for Iran to claim its 20-percent share of the Caspian, including valuable deposits. Thus, it is not likely that any agreement on a potential division of the Caspian Sea between all interested parties will be concluded anytime soon.

No foreign troops to be stationed

According to the key point of the landmark deal between the five littoral states, no foreign countries are entitled to navigate on the Caspian Sea and to deploy their military forces in the region. Hence, non-Caspian states cannot lease any ports and they cannot establish their own military bases. This issue is additionally bolstered by the Caspian Sea’s geostrategic position; the reservoir is located in the immediate vicinity of Turkey, the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Ukraine. Interestingly, this advantage has been recently used by the Russians, who carried out a series of air strikes in Syria, using the Caspian Flotilla or transferring their military units from the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Azov.

The issue seems quite up to date right now – over the last years, a lot has been said about launching potential American military bases in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan or Turkmenistan. In the first half of 2018, the United States concluded an agreement allowing to use Azerbaijani and Kazakh ports as transit points for shipping arms to Afghanistan, which caused some concern from both Russian and Iranian decision-makers. At present, there are grounds for wondering whether the provisions of the newly signed convention will make it possible to implement the aforementioned deal.

As a result, it appears that Russia and Iran will gain much more profits thanks to the above-mentioned ban on deploying foreign troops to the region. The territory of the former USSR is traditionally perceived by the Russians as the so-called “near abroad “, understood in terms of its special zone of influence where any interference of Western military forces might constitute a potential threat to its security. Similarly, Iran has also presented a distrustful perception of the international environment; the state has been both afraid of U.S. influence in the region – especially due to Washington’s recent activities – and a potential threat from Israel as the country has been developing its cooperation with Azerbaijan.

Perspectives for the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline

In addition, the convention affects the disputed question of the right to construct underwater pipelines on the seabed of the Caspian Sea. In particular, this issue concerns the construction of the so-called Trans-Caspian gas pipeline that would allow bringing Turkmen gas, through Azerbaijan, to European markets. The project has been discussed for almost two decades; nevertheless, Russia (and, to some extent, also Iran) has hitherto opposed any attempts to implement the plan as it sought to defend its own energy interests in Europe. According to the Kremlin, which was against the construction of the gas pipeline, further steps cannot be made due to the unclear status of the reservoir as well as an alleged need for the investment to be approved by all five coastal states considering possible damage to the natural environment.

In the light of the recent arrangements, constructing pipelines and cables along the seabed of the Caspian Sea shall be the responsibility of the countries whose sectors will be affected by the investment. Thus, if the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline were to be built, any possible implementation of the project would have to be approved only by Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, which may already mark a certain breakthrough. Nonetheless, also the provisions of the protocol on environmental impact assessment of the Caspian Sea, signed in July 2018, may prove to be relevant; according to a text of the treaty, other Caspian states will have the right to comment on the investment. Despite the fact that a similar situation has occurred also in the Baltic Sea – governed by the Espoo Convention – in this case, there emerged some suggestions that the Russian may take advantage of any environment consultations in order to delay the gas pipeline construction.

And even though the convention on Caspian Sea’s legal status makes it possible to conduct some actual works on the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline project, it is not so obvious whether the undertaking still has a solid justification. Today’s European gas market seems far more liberalised and diversified than it used to be in the previous decade when there were some plans to construct the pipeline. While Turkmenistan should be still interested in implementing the project – the more so that the state authorities are currently seeking new gas recipients, as evidenced by the TAPI Pipeline to India – the attitude of Azerbaijan does not seem so clear as both the country and its Western partners may perceive Turkmen gas as a certain competition for their own raw material deposits. Bearing in mind the time necessary to implement such a project as well as a potential need to expand the capacity of Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline, all interested parties will probably have to assume quite a long-term perspective before the investment is ultimately completed.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.