SPECIAL REPORTS

Date: 18 June 2018 Author: Mateusz Kubiak

Armenia: Change of Power

- Armenia’s new government was formed by Nikol Pashinyan, the leader of the April protests that had eventually led to the change of power in the country. For his cabinet, he has appointed ministers of foreign affairs and national defense, both of them being experienced specialists; such a decision should foster non-revolutionary politics in these domains.

- The new authorities do not intend to re-evaluate relations with the Russian Federation as the country guarantees Armenia’s security. They also assume that the alliance with Russia will be developed simultaneously with strengthening cooperation with the United States and the European Union.

- The main threat is the instability of the new government and its dependence on the support from representatives of the previous system of power. A possible inability to call snap elections may result in the country’s destabilisation and, as a result, may lead to an escalation of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

On May 8, the Armenian parliament voted in favour of the candidacy of Nikol Pashinyan (leader of the Civic Contract party allied in the Yelk electoral block) for the country’s new prime minister. Such a breakthrough was possible thanks to the approval from the previously ruling Republican Party of Armenia (also referred to as RPA; the party had an absolute majority in the National Assembly). Its members, even though they overtly declared lack of support for Mr Pashinyan, decided not to block his candidacy for the head of the government. As a result, Mr Pashinyan was supported by 59 MPs, including a dozen of the RPA members, which made it possible to avoid early elections.

The new cabinet included Mr Pashinyan’s close collaborators from the Yelk electoral block (such as two deputy prime ministers) as well as ministers delegated by two political parties: Prosperous Armenia and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun; in April this year, they finally supported the protesters) as well as non-partisan technocrats. In most cases, the composition of the new government received a positive response, especially in terms of ministries being of key importance from the point of view of foreign policy. Armenia’s ambassador to the United Nations until now, Zohrab Mnatsakanyan, will serve as foreign minister while the new Defence Minister Davit Tonoyan (former Deputy Minister of Defence) worked as minister for emergency situations in the previous government. Both ministers hold necessary competences and experience that should ensure relative stability in Armenia’s security policy.

The process of shaping new government was completed on June 7 when the National Assembly approved the program of Pashinyan’s cabinet. The document, apart from the “standard” agenda of work in particular areas, emphasised the need to separate business and politics (including the fight against corruption) as well as it urged to call snap elections. The content of the program states that the Armenian parliament in its present shape does not reflect the real will of the nation, which implies the need to choose new members of the National Assembly. Snap elections would be organised within a year after changing the electoral law and implementing all necessary systems that would ensure their full integrity.

April revolution

Nikol Pashinyan was elevated to the post of prime minister after mass demonstrations that took place for over a month in Yerevan and other Armenian cities. The protests broke out after electing and appointing Serzh Sarksyan the prime minister of Armenia. Mr Sarksyan is the chairman of the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA); in 2008-2018, he also served as Armenian president in 2008-2018 and was the author of the constitutional reform changing the country’s political system from semi-presidential to parliamentary one. It was generally believed that the amendment could have been imposed by Mr Sarksyan’s personal interests as, according to the current law, former prime minister could not be elected for his third presidential term. As a result, Sarksyan’s desire to retain power (interestingly, he denied rumours that he would take the post of prime minister after the amendment came into effect) has led to the outbreak of the largest social protests since the 1990s. The demonstrations were organized both by grassroots civic initiatives as well as political groupings related to Mr Pashinyan who quickly became the leader of the movement.

Although Mr Sarksyan’s candidacy for the prime minister’s office was the catalyst for the outbreak of social discontent, in fact, many protesters were not against the former president but they rather expressed their disapproval of political and oligarchic system he seems to represent. Since Armenia’s palace coup (1998), the country has been ruled by the so-called “Karabakh clan”, whose members (including Serzh Sargsyan or his predecessor Robert Kocharyan) started their political careers in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh. The politicians gained a dominant position in the country, although they also functioned with the coexistence of a number of partially independent oligarchs who had managed to build their empires before 1998 (such as for example former leader of the Prosperous Armenia political party Gagik Tsarukyan). The consolidation of this type of system over the last 25 years has led to social stratification in the country, and the percentage of people living below the poverty line fluctuates around 30 percent, even despite widespread economic emigration. As a result, the forced resignation of Serzh Sarksyan from the prime minister’s office (April 23) did not satisfy the demands of the protesters who claimed the appointment of a “provisional government” as well as urged for fair parliamentary elections.

Armenia’s domestic matters

Surprisingly, protesters’ demands did not concern foreign policy and, importantly, the country’s relations with the Russian Federation. It should be emphasized that during this year’s demonstrations neither anti-Russian slogans nor postulates of integration with the EU could be spotted, and the protests agenda concerned essentially the Armenian policy. It is important inasmuch as in recent years Armenians have expressed their increasing distrust towards Russia. Even though the Russian Federation is still perceived as the country’s only protector in the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the blockade imposed by Turkey, the Armenian perceptions of its activities are becoming more and more varied. In this respect, one can mention such factors as adverse effects on the country’s national economy due to its integration with the Eurasian structures, increases in gas and electric prices (as both are provided by Russian companies) and such events as the Gyumri massacre (2015) when a Russian soldier stationed at the local military base murdered an Armenian family of seven.

In their slogans, the protesters did not refer to geopolitics, which may explain why other countries got involved in the development of Armenia’s political situation only to a limited extent. Obviously, special attention was paid to the authorities in the Kremlin who traditionally perceive all kinds of color revolutions in the region as a threat to the legitimacy of their own system. In this case, the Russian activity that could be observed included primarily consultations with the current power camp (also between high-ranking officials) as well as Nikol Pashinyan and other protest leaders. The talks had both official and behind-the-scenes character, as evidenced by unexpected landing of the Russian government aircraft in Yerevan and its departure less than an hour later.

Alliance with Russia

According to the previous statements, it can be now assumed that the Russian authorities had actually accepted the power change in Armenia. Such a state of matters could be potentially explained by the fact that the new government apparently lacks real opportunities (and, perhaps, also the will) to change its hitherto relations with Russia. It results from the scale of the dependence of Armenia on the Russian protector; the Russians provide key military guarantees in the context of the conflict with Azerbaijan (including the military base in Gyumri and checkpoints on the Armenian borders); in fact, they also control Armenian energy and host hundreds of thousands of Armenians guest workers whose cash transfers from Russia correspond to over 8 percent of Armenia’s GDP.

As a result, Mr Pashinyan (both as a candidate for the post of prime minister and newly elected head of the government) has repeatedly assured that he had no intention to withdraw Armenia from the Russian-led structures of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the Collective Security Treaty. The head of Armenian government has already met Vladimir Putin at the EEU summit in Sochi where he indicated the unconditionally “allied and strategic” nature of the relations between both countries. These declarations are significant inasmuch as in previous years Pashinyan, still as a representative of the opposition, belonged to a group of explicit critics of the presence of Armenia in the Eurasian structures. Now new prime minister urges to maintain an alliance between Armenia and Russia but, at the same time, he also pursues to strengthen the country’s relations with the United States and the European Union. If Mr Pashinyan keeps in force the aforementioned priorities, he may guarantee a certain degree of continuity in Armenia’s foreign policy, although such a situation may be achieved also due to a more open approach to cooperation with Western partners (for instance by implementing provisions of the comprehensive and enhanced partnership agreement concluded by Armenia and the European Union in 2017).

Karabakh issue

Armenia’s new prime minister issued a declaration on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the peace talks. A day after he was appointed the new head of the government, Mr Pashinyan paid a visit to Stepanakert (capital of the self-proclaimed Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh) where he made a number of declarations in this regard. Armenian prime minister urged about the need to allow the region of Nagorno-Karabakh to enter the talks under its full-fledged participance (they are currently represented by Armenia, Azerbaijan as well countries on the authority of OSCE: Russia, the United States and France, within the 3+2 format). Such a demand, which could also be found in the government’s official program, has been well received both in Armenia and in Karabakh (as Mr Pashinyan clearly seeks to get support from the Armenians living in the region; nevertheless, it was criticized by Azerbaijan whose authorities recognise the Karabakh Armenias in terms of the separatists. In addition, Mr Pashinyan pointed to two further conditions for the conflict resolution: first, Azerbaijan will be obliged to reject its wartime rhetoric and, secondly, the authorities in Baku should express its readiness to recognize the right of Karabakh residents to self-determination.

It seems that the above-mentioned statement can be interpreted in the context of Armenian domestic policy. Armenia’s new head of the government had better strive to maintain his current support, also the one of still-influential veterans. Moreover, his decision to take a conciliatory position on the Karabakh issue would not be accepted by the society. At the same time, it is unlikely than Mr Pashinyan decides to change his political course and to reorient on the issue during the “transitional” period between assuming power in the country and holding snap elections. So it seems that no breakthrough is expected in the near future as part of the ongoing peace process. On the contrary, it can be assumed that such period of relative instability in Armenia may be conducive to the escalation of tension. It is significant that in May this year Azerbaijani forces managed to occupy 16 km2 of the so-called no man’s land on the border in Nakhichevan (Azerbaijan exclave separated by a belt of Armenian territory), which constitutes twice as large territorial change as in the case of the Four-Day War in 2016.

Fragile stability

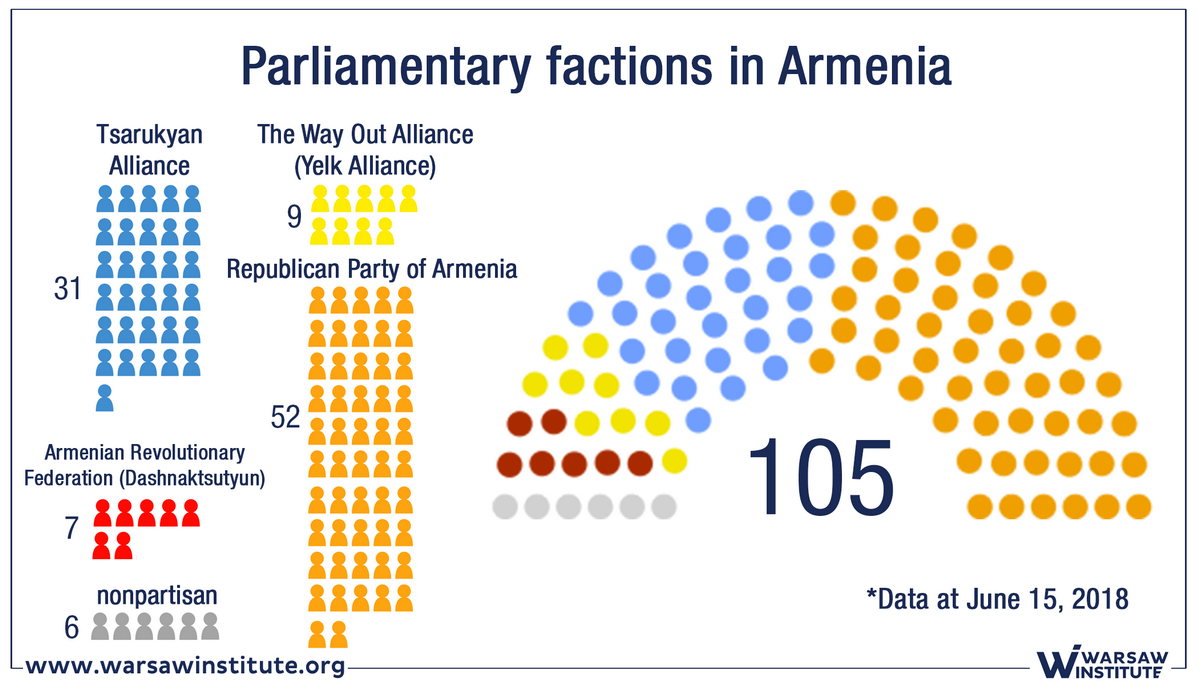

At the moment, there is still no certainty as to the further development of events in Armenia. In this case, the key factor may concern the distribution of forces in the parliament, which obliges Mr Pashinyan to base his cabinet on politicians belonging to the current power elite. It concerns the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (which provided its support to Mr Pashinyan as both parties co-formed the ruling coalition), the Prosperous Armenia party (along with its former chairman Gagik Tsarukyan who supported current prime minister only after the resignation of Serzh Sarksyan as he had previously endorsed the Republic Party) as well as splinter groups from the Republic Party of Armenia (on June 8, such a group consisted of 6 people, including influential oligarch Samvel Aleksanyan). Support from all the groups is necessary to change the electoral law and to call early elections, which remains the government’s main goal. Theoretically, such a large coalition will have a majority in the parliament, but it is not sure whether it will actually cooperate in favor of changes that could deprive many of its members of the parliamentary mandate.

Government’s potential problems with calling snap elections constitute today the main threat to the stability in Armenia and neighbouring countries. If Mr Pashinyan’s actions are obstructed by some individual parliamentary factions, the situation may result with chaos in the country. In addition, such state of matters may be followed by subsequent social protests and, in most extreme cases, even by attempts to dissolve the parliament with no respect to the existing rules. The country’s possible destabilisation will also mean the risk of escalation in Nagorno-Karabakh, which would threaten the security in the entire region. In this context, it is desirable that both the United States and the European Union be ready to support the Armenian electoral system reform and implementing snap elections.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.