THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 12 March 2018 Author: Nicholas Siekierski

American Relief and Poland’s Independence

Later this year, Poland will celebrate its centenary of regaining independence on November 11, 1918. There will surely be many speeches and ceremonies, but what emphasis will be placed on the foreign country and the Pole who deserves much of the credit for this event?

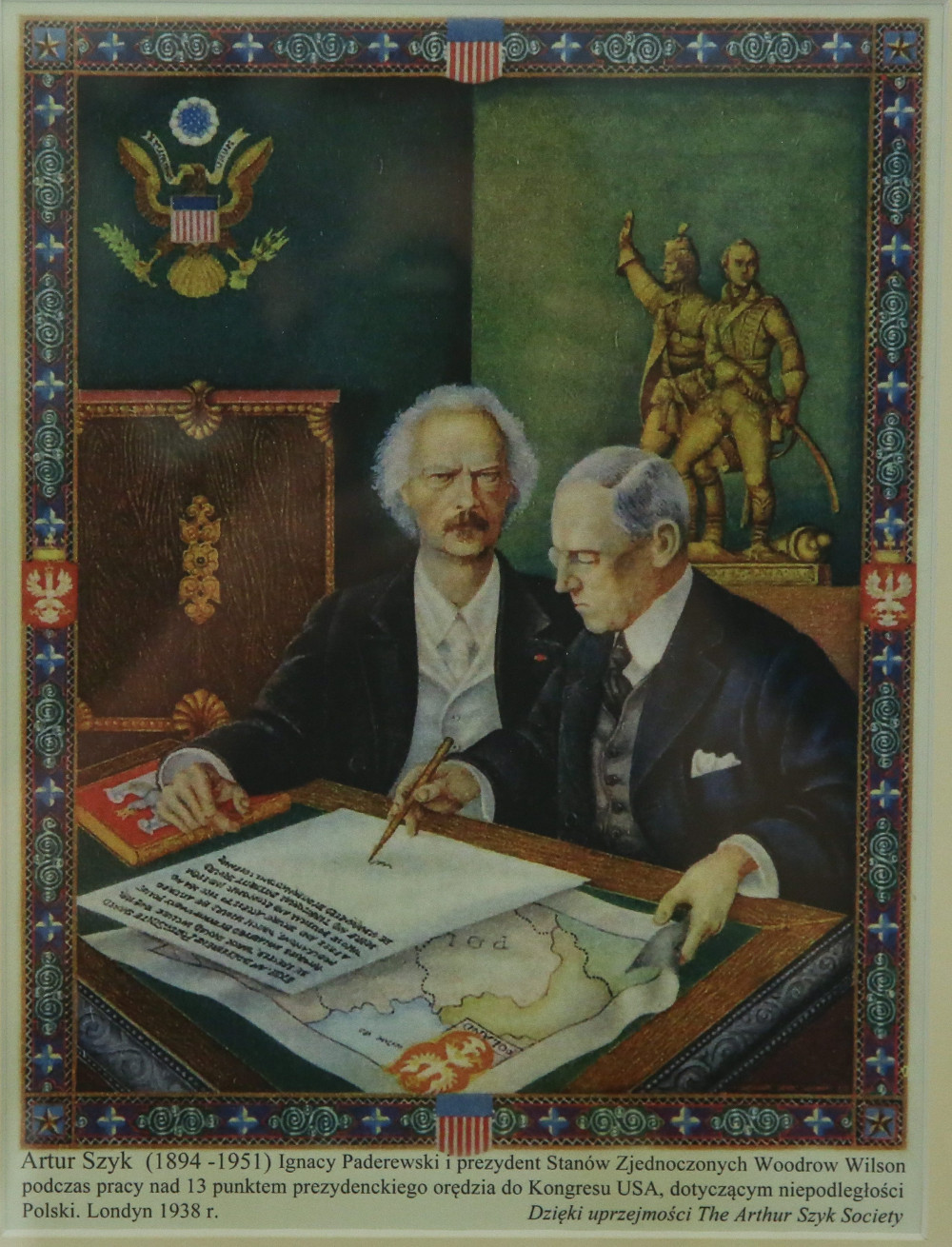

I am speaking of the United States, then emerging as a superpower, and Ignacy Jan Paderewski the virtuoso pianist-statesman, whose efforts ensured American support for Poland’s liberation from one-hundred and twenty-three years of enslavement.

The attempts by Herbert Hoover, Edward House and President Woodrow Wilson to negotiate a relief program for Poland modeled on the Commission for Relief in Belgium, though unrealized during the war, brought the plight of Poland to the world stage. This contributed to an increased, international political interest in the distant land. Not only was the deplorable humanitarian situation publicized, but so was the reality of Poland’s subjugation to three neighboring empires. The post-war operations of the American Relief Administration buttressed the proclamations made by the American government in support of Polish independence in the preceding years.

The Americans did not take an interest in Poland simply out of a sense of justice and morality (though these were important factors), but because they were induced to do so by Poles in America, most notably by Paderewski. It was largely Paderewski’s personal friendship with Edward House, Wilson’s closest adviser, that impressed upon the President the importance of Poland’s independence as a condition of peace after the war.

Although some of the most influential men in America took a great interest in seeing Poland regain her freedom, their support was not unconditional. While American influence on Polish politics appears to have been measured and intermittent (certainly when compared to Poland’s troubled history with Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary) it was brought to bear on occasion. The most effective form of this leverage was the threat of withholding critical food aid to the newly reborn nation in the early months of 1919, unless the country’s civilian and military leaders recognized the necessity of a strong civil government with Paderewski as prime minister.

American Polonia and Polish Relief

The American government was preoccupied with a plethora of matters, even before entry into the war. The maintenance of its focus, even inconsistently, on both the humanitarian and independence issues surrounding Poland, was due largely to American Polonia.

Major immigration into the United States from Poland took place between the late 19th and early 20th century. Though exact numbers are impossible to determine, between two and three million Poles lived in America by 1914. The major concentrations were in the large cities such as New York, Pittsburgh and Detroit, though the undisputed center of American Polonia was Chicago.

With Poland partitioned between Germany, Russia and Austria, political life was necessarily carried out by Polonia émigrés, the most influential centers being in the United States and Western Europe. The ideological dividing line in Polish émigré politics in the early 20th century was between nationalism and socialism. Though there were many figures associated with both movements, the best known were Roman Dmowski and Józef Piłsudski, the former being the leader of the National Democratic Party and the latter being the most well-recognized leader of the Polish Socialist Party (though he left the party at the outbreak of World War I.)

These political divisions were also present in the United States, though groups associated with nationalists would dominate. Over the course of the war, the nationalists would side with the Entente powers, based on the belief that Polish independence could only be achieved when her mortal enemy, Germany, was defeated. The socialists on the other hand, sided with the Central Powers, specifically with Austria (Piłsuski’s base of operations was in the Austrian-controlled Galicia region), believing the defeat of Russia, Poland’s other mortal enemy, to be the only way that a Polish state could re-emerge. As the chief financial support base for Polish political activity in Europe during World War I, American Polonia would gain paramount importance among Polish leaders.

The key figure in Polonia politics in America turned out to be neither Dmowski nor Piłsudski (neither spent very much time in America, with the latter only visiting once while traveling to Japan), but of all people a world-renowned concert pianist, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Having toured Europe and America extensively for many years, and being fluent in English (among other languages), Paderewski was the most famous Pole in the world at the time. His activities during World War I as Poland’s most eloquent champion would also make him the country’s best known political figure.

Paderewski, along with Nobel-prize-winning writer Henryk Sienkiewicz, formed the General Committee of Relief for War Victims in Poland (Generalny Komitet Pomocy Ofiarom Wojny w Polsce) in January 1915, which came to be informally known as the Vevey Committee, named after the Swiss city in which they were headquartered. The committee was the epicenter of the small, but highly influential group of Polish émigrés that would help to focus the efforts of Polonia organizations in the United States.

Also established in the U.S. in October 1914 in Chicago, was the Polish Central Relief Committee (Polski Centralny Komitet Ratunkowy, PCKR), a federation of major Polish organizations including: the Polish Roman-Catholic Union, Polish National Alliance, Polish Falcons’ Alliance, Alliance of Polish Women, National Council and others. This organization was influenced by the National Democrats and Dmowski.

The National Defense Committee (Komitet Obrony Narodowej, KON) was formed in 1912 in Pittsburgh and enjoyed a brief period of hegemony over Polonia politics. However, once it became clear that KON was not a broadly representative organization, and that the majority of their leadership were partisans of Piłsudski’s Polish Legions, the coalition collapsed. The KON would play a minor, oppositional role in American Polonia politics.

The Polish Central Relief Committee and Vevey cooperated, thanks to Paderewski’s arrival in America in April 1915 and his tour of Polonia organizations around the country. Disagreements over whether the relief organizations should engage in political actions or remain apolitical led to strong antagonisms between the Vevey Committee and the KON. The latter’s support of the Central Powers and the association of Vevey with the Entente, and their respective opinions as to which side would better realize Polish independence, was the basis of this friction.

In total, the Vevey committee received approximately $4 million in donations during the course of the war, $2.5 million of which came from the United States. This was quite a sum, accounting for the fact that a majority of donations, at least from the U.S., were from working class Poles who earned less than $400 per year.

While American Polonia was a force to be reckoned with, ultimately its greatest influence was realized by one man. Paderewski enjoyed the respect, financial support and access to media platforms (namely newspapers and public appearances) afforded by Polonia, which allowed him to carry on practically full-time political work from 1915 onward. Though sometimes vain, naive and prone to nervous breakdowns, Paderewski was able to create a personal connection with the most influential men in America at the time. His efforts highlighted the issues of Polish relief and independence in a way that no other individual or group could come close to.

Paderewski, Colonel House and Woodrow Wilson

Paderewski’s activities on Poland’s behalf would eventually lead him to meet President Wilson’s closest advisor, Edward Mandell House on November 12, 1915. The purpose of the meeting was Paderewski’s desire to impress upon House the need for Polish relief and to request assistance in securing aid from the administration.[1] Colonel House (an honorific title, as he had no military background) was immediately taken in by Paderewski’s dynamism, energy and patriotic zeal. “We were friends at our first meeting. I knew at once that I was in the presence of a great man, and one with whom it would be a delight to work. He inlisted [sic] my sympathies for Poland.”[2] House later reflected on the importance of the Paderewski friendship to his involvement in the Polish cause:

“It was solely through Paderewski that I became so deeply interested in the cause of Poland, and repeatedly pressed upon the President Paderewski’s views, which I had made my own. That was the only real influence regarding Poland that I counted, and I am sure if Woodrow Wilson were alive he would tell you that he was actuated by the same impulse that governed me.”[3]

Years later, the value that Paderewski tied to the friendship with House, whom he referred to as “Poland’s providential man”[4], took tangible shape in the form of a statue of House that he funded in 1932 in Warsaw’s Skaryszewski Park. It is one of the few statues of Americans in Poland (other than the busts of Ronald Reagan and George Washington in Warsaw, and Woodrow Wilson in Poznań). While President Wilson gets credit for facilitating Poland’s independence, it is clear that House’s interest in the matter, further inspired by Paderewski, led him to emphasize its importance upon the President:

“The close relationship growing between House and Paderewski had the effect of gradually aligning the United States government with the faction in international politics represented by the maestro. Although other factors were involved, the personal element represented by the Paderewski-House relationship should not be discounted, especially in the earliest American involvement in Polish affairs.”[5]

One of the early effects of Paderewski’s and Polonia’s efforts was the declaration by Wilson of January 1, 1916 as “Polish Relief Day”, following a resolution passed in Congress, with the Red Cross serving as the administrator of money collected. Though the gesture was received with great excitement among Poles, only $64,000 was raised in all of 1916 through this charitable endeavor. A combination of factors was at work here, though the dominant one was likely the far greater familiarity of Americans with fundraising appeals for the Commission for Relief in Belgium, chaired by Herbert Hoover, which was collecting donations in the millions of dollars each year.[6]

The most practical results of the Paderewski-House relationship during the war was the influence on Wilson that led to several important references to Polish independence in his major speeches.

“Sympathy for the war suffering of the Poles merged with sympathy for their demand for the unity and independence of their nation. In this way the restoration of Poland became a war issue for a large public long before it was accepted by the foreign offices of Europe…popular support of Polish aspirations gained headway more rapidly in America than elsewhere, and this championship…was to be given new force in President Wilson’s speech on January 22, 1917.”[7]

This timeframe, several months before America’s entry into the war, was part of a final effort to negotiate peace in Europe with the United States as the mediator. Although more of an illustrative example than a powerful statement of intent, the Polish question was given international exposure in a way that it had not received before:

“I take it for granted, for instance if I may venture upon a single example, that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, and autonomous Poland, and that henceforth inviolable security of life or worship, and of industrial and social development should be guaranteed to all peoples who have lived hitherto under the power of Governments devoted to a faith and purpose hostile to their own.”[8]

Nearly one year later, after America had already entered the war, Wilson gave his landmark “Fourteen Points” speech on January 8, 1918. The thirteenth point addressed Poland and was a more definitive statement of Wilson’s vision for a free Poland:

“An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.”[9]

A closer analysis of the point reveals that it was not as much of a ringing endorsement of Polish independence as some had hoped. The use of the word ‘should’ instead of ‘must’ (the latter having been applied to Belgian independence in an earlier point) indicated that a controversy existed on the matter. As was explained to Paderewski by House later, it was not an ultimatum. In Professor Marek Biskupski’s analysis, “Essentially, the very principle of Polish independence was reduced from the level of basic war aims (signified by the use of “must” in the case of Belgium) to that of ethical endorsement.”[10] Wilson’s statement may also reflect an academic and theoretical view of international affairs rather than a practical one. The border conflicts that engulfed Poland from the moment independence was declared were a natural consequence of reconstituting a new state surrounded and populated by ethnic groups with conflicting claims. Wilson’s abstract way of thinking did not account for this however:

“He [Wilson] was convinced that the moral good of reconstituting Polish independence could be had without major territorial revisions. His conversion to the cause of Polish independence was essentially moralistic: part of a larger moral vision of world order. Within this new order the demands of realpolitik discussed by his own advisers, could be ignored as no longer valid…In reality he was merely the champion of the idea of Polish independence, not of a rational program to assure its maintenance.”[11]

Wilson was frustrated by Poland’s initiative to establish its borders through military force, rather than wait for the wise men of the Paris Peace Conference to draw the new boundaries on a map. Herbert Hoover provides an insight into Wilson’s mindset in his tellingly titled America’s First Crusade, “He, however, believed and continued to believe, that he could bring a ‘new order’ to the Old World. The words ‘new order’, ‘justice’, ‘right’, ‘reason’ were constantly upon his lips. He believed that he had the power to impose this new order upon Europe, that it would remove the major cause of their incessant wars.”[12] America’s involvement in the peace process would be a great experiment into how well its values could be transferred to Europe’s new nation states with their conflicting interests.

All the Western Allies declared support for Polish independence by Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. The United States was the first world power to commit to self-determination of nations in Eastern Europe, at least in principle. The establishment of the first new government in Poland by Piłsudski would test the principle in practice.

Humanitarian Aid as Political Leverage

In December 1918, it finally became possible to send direct aid from America. A “food mission” departed France under the instruction of Herbert Hoover, then Food Administrator of the United States under President Wilson. By January 1919, when the mission had arrived in Poland, Hoover had become the director of the American Relief Administration (A.R.A.), tasked with providing famine relief to Europe. At the request of the Polish government and following the reports of the food mission describing conditions in Poland, it was decided to provide Poland with aid. Ultimately the mission would help establish more than four-thousand “kitchens” run by tens of thousands of Polish volunteers, serving daily meals to over one million Polish children and nursing mothers by 1920.

Herbert Hoover had been explicit in his instructions to the mission: “Keep entirely out of politics. There are political missions assigned to political work, and we should forward to them any matters of interest in their work, or to the advantage of Poland in the general Allied cause, but your work is entirely that of relief.”[13] However, in his memoirs written several years later, Hoover relates an incident that was quite the opposite of his instruction:

“Dr. Kellogg [chief of the mission] advised me of the impossible political situation. He felt there was only one hope and that was for Piłsudski, who had the army’s backing, to be put on a pedestal. To close up the factions, he recommended that Ignacy Paderewski, the favorite of all Poles, should be placed at the head of a stronger cabinet as Prime Minister and take control of the civil government. Not only did Paderewski hold the imagination of all the people, but he was a man of superlative integrity, deeply imbued with democratic ideals. Dr. Kellogg asked that he be authorized to inform Piłsudski that unless this was done American co-operation and aid were futile. I did so and got the hint reinforced from President Wilson. As a result, Piłsudski was elevated to the position of “Chief of State,” and Paderewski became Prime Minister on January 16.”[14]

Nowhere in his writings does Vernon Kellogg confirm that this incident did indeed take place. However, the incident is corroborated by Wilson himself at one of the Paris Peace Conference meetings on May 17, 1919: “President Wilson said that M. Paderewski had a letter in his possession from Mr. Hoover, informing him that aid would only be extended to Poland so long as he was in charge.”[15] The context of the discussion was the apparent refusal of the Poles to cease operations on the Ukrainian front, despite Paderewski’s protest and threat to resign.

There is dispute among scholars as to the veracity of Hoover’s statement, in one case blaming him for a memory lapse.[16] While it’s not inconceivable that Hoover confused some of the facts, the more questionable part is that Kellogg himself would suggest such a serious intervention into Polish affairs. It is more likely that Hoover, if not Wilson or House, put forward this idea. The statement by Wilson in Paris supports this. In the spring of 1919 Wilson also suggested withholding aid to Poland if certain issues relating to the Jewish minority were not addressed. This further strengthens the idea that the U.S. government was willing to use food aid as leverage on both the political structure and policy of the Polish state, at least in the early months of its existence.

The main reason for this influence was the cautious attitude of the Americans towards Piłsudski. Ironically, the Polish nationalist faction, which had gained so much support in America both from Polonia and the U.S. government, was subordinated to Piłsudski and his circle, which had been largely frozen out of funding and political influence among the Allies during the war.

“Hoover’s admiration for the Polish artist may have been the main factor in his expressed preference for Paderewski as the head of government. Also, Piłsudski’s past association with socialism, though it was the Polish type of intensely patriotic and democratic socialism, may have bothered Hoover, who throughout his life was a consistent opponent of any form of socialism.”[17]

The apparent intervention of Hoover or Wilson on Paderewski’s behalf was an attempt to tip the scales in favor of an individual that they felt valued democratic principles, was an idealist like they were, and most importantly, was someone they knew and could work with. Paderewski returned to Europe on the SS Megantic, still a British troopship at the time, and stopped in London for consultations with the British Foreign Office prior to his return to Poland[18], which shows the measure of importance that he was treated with by the Allies. Piłsudski on the other hand was seen differently:

“The General was a revolutionary soldier. He was wholly without experience in civil government. He was a dictatorial person with a strange mixture of social and economic ideas. He set up a ministry mostly of military and doctrinaire character that was concerned with such matters, rather than with the heartbreaking and immediate job of governmental housekeeping.”[19]

Publicly Hoover showered Piłsudski with praise during his 1919 visit to Poland, “Poland is fortunate in having in her leadership two out of the six or seven great idealist statesmen of the world, Mr. Piłsudski and Mr. Paderewski.”[20] However, this type of rhetoric was more a matter of statesmanship and wishful thinking, while his memoirs more closely present his true beliefs. Despite the obvious preference of Allied leaders, it’s debatable whether their interventions played a decisive role in the composer’s appointment as prime minister of Poland by Piłsudski. The Chief of State recognized Paderewski’s popularity in both Poland and abroad, and the role he could play representing Poland at the Paris Peace Conference. It is nonetheless an episode that highlights the importance America placed on Poland, especially as the Bolshevik Revolution threatened to spill over the borders of Russia, as it did in 1920. The tremendous resources poured into Poland by the U.S. served as a kind of insurance policy meant to increase the physical wellbeing of its citizens and to jumpstart the economy of the newly reborn nation.

Crusade for Peace

Despite the failure of attempts to provide relief to Poland during World War I, the issue of Polish independence was brought to the forefront, and post-war relief carried out by the A.R.A., while an extraordinary humanitarian endeavor in its own right, was a means of ensuring that Poland remained free to the greatest extent that America was able to do at that time. As Herbert Hoover saw it, “Our Americans had been more detached from the war, and had the least degree of hate. Our statesmen were free to rise above it. We had no ideas of acquiring territory or reparations or profit. What we wanted was for Europe to so order itself as to end wars.”[21] America’s influence on Paderewski’s selection as Prime Minister of Poland, even if not the decisive factor, shows that when Europe failed to “order itself” in an acceptable manner, the United States would push events in the direction it preferred.

The 116,000 American lives claimed in “the war to end war” was the price of entry onto the political and cultural battlefield of Europe. The entire post-war relief project, which extended well beyond Poland, coupled with the Paris Peace Conference and League of Nations, was meant to be the framework that would realize a lasting peace. While it is easy to dismiss it as a hopelessly naive enterprise that was doomed to failure from the start, understanding the motivation behind it provides an insight into the pioneering mindset of American leaders at the time. Their horror at Europe’s self-destruction that left nearly twenty million dead, coupled with a uniquely American approach to solving problems, motivated their desire to forge a new paradigm for Western civilization.

This underappreciated aspect of Poland’s modern history should get its due during the celebrations and events to come later this year. The excellent exhibit “From Poland with Love”, created by the History Meeting House and the Karta Center in Warsaw recently, is a perfect example of how this story should be told. The exhibit highlighted the extraordinary symbol of gratitude created by the Poles in thanks for American relief: 109 volumes containing 5.5 million signatures (twenty percent of the pre-war population) and beautiful illustrations, delivered to the White House in 1929. A searchable database has been created online for Poles to track down the signatures of their ancestors. Both of my grandfathers, then young boys, signed the volumes. Poland’s fate could have been far different were it not for America’s intervention on her behalf and the unlikely friendship between Colonel House and Ignacy Paderewski. Poland’s heavy reliance on the United States for its security today is reason enough to highlight these historic ties of friendship between the two nations.

[1] Edward Mandell House Papers, Series II, Diaries, Volume 3, Yale University Library Digital Collections, http://digital.library.yale.edu/cdm/ref/collection/1004_6/id/3841.

[2] M.B.B. Biskupski, The United States and the Rebirth of Poland: 1914–1918, (St. Louis: Republic of Letters, 2012), 134.

[3] House to Orłowski, January 15, 1931, House Papers, Box 84, f. 2916.

[4] H. Paderewska, Memoirs, 1910–1920, (Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press, 2015), 88.

[5] Ibid. 136.

[6] M.B.B. Biskupski, op.cit., 141.

[7] H.H. Fisher, America and the New Poland, (New York: Macmillan, 1928), 90–91.

[8] M.B.B. Biskupski, op.cit., 239.

[9] President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, January 8, 1918, Yale Law School, The Avalon Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/wilson14.asp.

[10] M.B.B. Biskupski, op.cit., 331–332.

[11] Ibid. 406–407.

[12] H. Hoover, America’s First Crusade, (New York: Scribner’s, 1942), 3.

[13] W.R. Grove, War’s Aftermath, (New York: House of Field, 1940), 36.

[14] H. Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure, 1874–1920, (New York: Macmillan, 1951), 356–357.

[15] U.S. Department of State, Papers Relating to Foreign Relations of the United States: Paris Peace Conference 1919, Washington D.C. Government Printing Office, 1919, 5: 676, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/FRUS.FRUS1919Parisv05.

[16] T. Komarnicki, Rebirth of the Polish Republic: A Study in the Diplomatic History of Europe, 1914–1920, (London: William Heineman, 1957) 261.

[17] J. Lerski, Herbert Hoover and Poland: A Documentary History of a Friendship, (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1977), 8.

[18] H. Paderewska, op.cit.,121.

[19] H. Hoover, Memoirs, 355–356.

[20] J. Lerski, “Hoover Address at Lwów city hall, August 15, 1919”, 82.

[21] H. Hoover, America’s First Crusade, 10.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.