THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 1 August 2018 Author: Mariusz Klarecki, PhD

Art Collections in Bombed Warsaw September 1939

The very first concerns about the fate of Polish art work during the times of potential armed conflict emerged in the autumn of 1938.

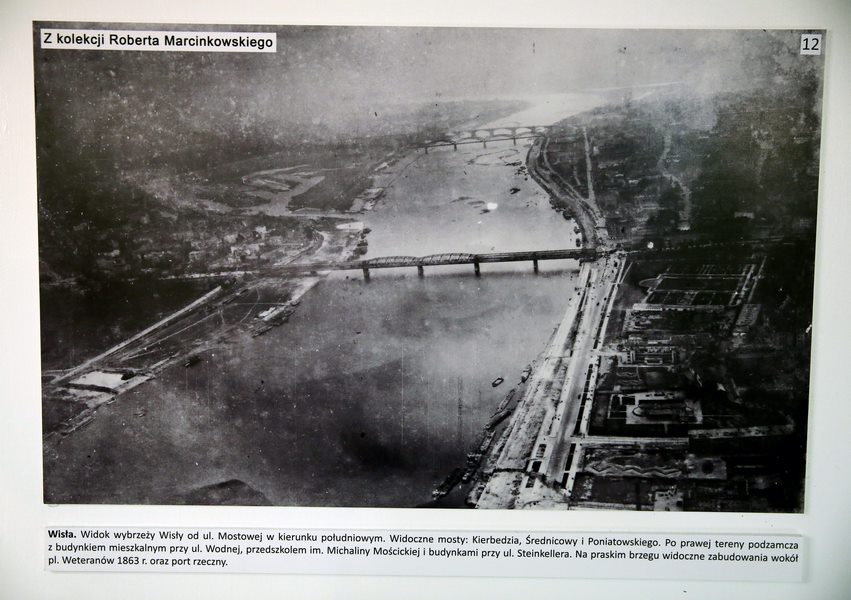

Warsaw, February 26, 2015. Exhibition of previously unpublished aerial photographs of Warsaw at the Jabłkowski Brothers’ House in Warsaw. The photos were taken by the Luftwaffe on September 20, 1939. © PAP/Tomasz Gzell

Warsaw, February 26, 2015. Exhibition of previously unpublished aerial photographs of Warsaw at the Jabłkowski Brothers’ House in Warsaw. The photos were taken by the Luftwaffe on September 20, 1939. © PAP/Tomasz GzellAt the initiative of museum workers, it was possible to engage Poland’s Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment in talks on how to secure collections in case of war. The topic was even mentioned during a specially organized conference. As written by Stanisław Lorentz, Director of the National Museum in Warsaw: “Neither state nor municipal authorities made any decisions and – as it turned out – neither museums nor – as far as I know – libraries and archives were prepared in the event of a war, which disastrously affected the extent of losses during the siege of Warsaw in September 1939.” In August that year, the employees of the National Museum in Warsaw decided to prepare 230 chests in the basement of the building; they could be used to pack exhibits during a possible conflict[1].

The priority was to protect the museum collections, with special attention being paid to the intensely bombed Royal Castle. Stanisław Lorentz mentioned that just after the outbreak of the war, “the museum received both large and small deposits that came from both destroyed apartments as well as were brought by people leaving the capital”[2]. In addition, the institution had already disposed of deposits from private individuals. At the beginning of the bombing performed by the German aviation, an artillery shell destroyed to a great extent a “very valuable deposit of General Bylewski; filed at the Museum in 1932, it consisted of 71 clocks dating from the 16th to the 19th century, many of them being either Polish or foreign uniques. The collection, which was supposed to be donated to the Museum as a gift, encompassed many large-size, both cabinet and wall, clocks – difficult to be packed and moved […] out of the entire collection, only 20 pieces survived –, all of them in a very poor condition[3].” Michal Walicki, an employee of the Royal Castle, made an unsuccessful attempt to persuade Dr. Ludwik Bryndz-Nacki to store his valuable possessions in the secure basement of the National Museum building. The collection was completely destroyed during the bombing of Warsaw in September 1939. Its owner, who lived near Krakowskie Przedmieście Street, managed to gather 112 paintings of renowned Polish painters as well as those of slightly lesser known Flemish and Dutch masters, dating from the 17th century. The burned works of art had already been known to the general public due to the fact that their proprietor had frequently displayed them during numerous national exhibitions, thanks to which it was possible to preserve some photographs of many of the objects[4].

While the bombing of the capital was intensifying, art works and antiques from all over the city – “including Potocki’s very valuable collection kept hitherto in the palace at Krakowskie Przedmieście Street 15 and the residence of Janusz Radziwiłł at Bielańska[5] Street” – were transported to the spacious basement of the Museum. According to Lorentz, mansions, inhabited by nobles right before the outbreak of the war, were left open, as their dwellers had fled the city in a hurry. In this way, any property, which previously belonged to aristocrats, could be easily looted or ravaged. In addition, many residents of Warsaw who had their palaces and mansions outside the city were affected by severe losses. Due to their close location to the capital, some of the estates were subsequently occupied by German troops who were getting ready to siege the city. Such was the case of the “Basiówka” residence, positioned in the Młociny district and owned by Czesław and Irena Ludwig. On September 22, the house and all its equipment were set on fire by Wehrmacht officers. The fire devastated antique furniture, old prints, bronzes, carpets as well as paintings by Polish and foreign[6] masters.

One of the most important goals set by the Luftwaffe aircraft was the headquarters of the Staff of the Defence of Warsaw, based in the Zamojski Palace (Nowy Świat Street 67). The backyard of the building held a so-called “Antiquarian quarter” located around the following streets: Mazowiecka, Świętokrzyska, Nowy Świat, Krakowskie Przedmieście and Traugutta. As a result of the intensified bombings in this part of the city, many art works in the antiquarian salons were badly[7] damaged. According to Władysław Płachciński, “all of them [salons] burnt: Klejman, Szuberg from Lviv, Abe Gutnajer, Bernard Gutnajer, Czaja, Kaniewski, Studzinski, Grodecki – in Jerusalem Avenue – all of them burnt completely, without a trace”[8]. Jak dalej wspomina Płachciński – “Sapiecha na Oboźnej zainkasował pięć bomb …” In addition, five bombs hit the house of Mr. Sapiecha at Oboźna Street: the blast completely destroyed the corner of his dwelling on the first floor where he had a large flat filled with various objects. Now the place resembles rather a garbage disposal while old Sapiecha, unwashed and wearing an old dressing gown, has been moping around in the ruined apartment for 13 months, searching through the rubble and hoping to find some buried fragments of sculptures, shells, furniture debris; he has been collecting remains in the rooms; poor man! He has the intention to glue and restore them!”[9].

The list of Warsaw’s most famous antique shops burnt in September 1939 included also “Palac Sztuki” [The Art Palace], located at Trębacka Street 4. In the appendix to the loss questionnaire submitted to the Department of War Loss Management of the Capital City of Warsaw, Józef Smokalski’s wife detailed the losses of antiques and art works, both in their burnt apartment and the antique shop at Trębacka Street 4 and 5, dividing them into those created in 1939 and 1944. Following the city’s bombing in September 1939, the total sum of damages amounted to 53,000 pre-war zlotys, which constituted a significant expense as compared to the overall cost suffered during the Warsaw Uprising (39,500 zlotys). For example, numerous paintings of renowned Polish masters (including J. Brandt, J. and W. Kossak, J. Malczewski, J. Chełmoński, T. Axentowicz, J. Fałat, A. Grottger and J. Lampi) were eventually burned and destroyed. In addition to the above-mentioned art works, the antique shop offered carpets, some porcelain, glass, silver and furniture. Both before the war and during the occupation, “Pałac Sztuki” was perceived as being one of the largest antique shops, being able to sell many valuable objects.[10]

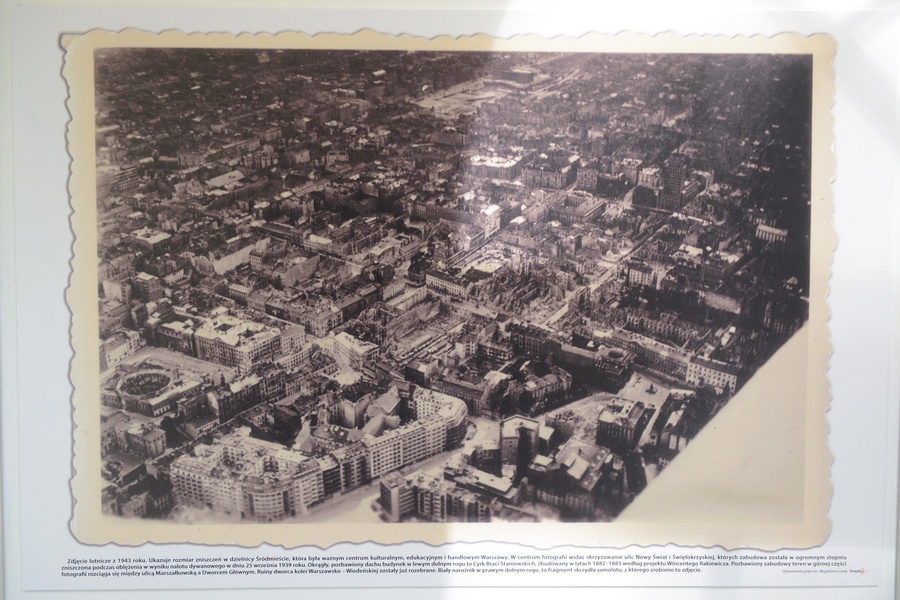

Warsaw, February 26, 2015. Exhibition of previously unpublished aerial photographs of Warsaw at the Jabłkowski Brothers’ House in Warsaw. The photos were taken by the Luftwaffe on September 20, 1939. © PAP/Tomasz Gzell

Warsaw, February 26, 2015. Exhibition of previously unpublished aerial photographs of Warsaw at the Jabłkowski Brothers’ House in Warsaw. The photos were taken by the Luftwaffe on September 20, 1939. © PAP/Tomasz GzellAnother place completely burnt in 1939 was “Salon Sztuki” [Art Salon], owned by Kazimierz Kaniewski and located at Nowy Świat Street 64. As written in the “Certificate”, a document issued by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Warsaw on September 5, 1945: “[…] during the war, the enterprise was destroyed twice: once in September 1939 and again – as a result of the last attempts to save the capital. The losses suffered, both by our cultural achievements and the enterprise, are so significant that it is impossible to assess them at the moment. More than 20,000 art works (including 2,300 paintings), based in 40 rooms were completely destroyed by fire”.[11]

The bombings of the capital devastated also a large collection belonging to an industrialist Edward Natanson, founded in 1850 by Ludwik Natanson. Edward Natanson occupied a 10-room apartment at Krolewska Street 10. As a result, the collector lost 60 paintings of outstanding artistic value by artists such as: J. Matejko, A. Gierymski, J. Chelmonski, J. and W. Kossak, J. Falat, S. Wyspianski, J. Brandt, W. Podkowinski, and J. Malczewski, J. Lampi, M. Bacciarelli as well as those of excellent Western European painters: J.B. Greuze, F. Boucher, G. Reni, Dutch masters and many others. Moreover, the fire ravaged numerous pieces of eighteen-century French furniture, a high-class collection of Meissen porcelain and as many as 18 vases produced in the eighteen-century royal manufactory of King Stanisław August Poniatowski in Belweder[12]. It is estimated that Polish museum collections across the country currently dispose of more or less the same number of items designed in the above-mentioned manufactory.

Warsaw, September 29, 2017. Opening of the exhibition “Destruction of Warsaw in September ’39 in Polish and German Photography” at the Province Governor’s Office in Warsaw. © PAP/Jakub Kamiński

Warsaw, September 29, 2017. Opening of the exhibition “Destruction of Warsaw in September ’39 in Polish and German Photography” at the Province Governor’s Office in Warsaw. © PAP/Jakub KamińskiSince the very first days of September 1939, all railway stations in Warsaw had been heavily bombarded. The warehouses, located just next to them, held large quantities of food supplies as well as other goods belonging to people who had managed to leave border regions just before the German invasion of Poland. In addition, the railway depots could store a large amount of private property, including pieces of art that had previously served as household equipment. On September 4, precisely at 5 p.m., German aircraft bombed the Main Railway Station and the Western Railway Station[13] in Warsaw. During the bombardment of the former, a certain Jozef Trawinski lost his entire chattel that he had sent by train from Sosnowiec to Warsaw on September 1, 1939. It was only five days later than he received a message stating that his possessions had been destroyed in a fire during a raid on the station. The package contained the following paintings: “Chrystus w ogrodzie” [Christ in the Garden] by D. Teniers, “W stepie” [In the Steppe] by J. Brandt, “Kapliczka” [The Shrine] by Z. Kłosowski, “Pejzaż” [Landscape] by J. Chełmoński and “Trębacz” [The Trumpeter] by M. Gierymski. In addition, several other artistic craft objects were completely shattered.[14]

Customs warehouses based at Eastern Railway Station started burning on September 4; it was on that day when German aviation carried out intensive bombing of the city. Material losses suffered by the Gora family comprised art works and antiques, including a collection of 18 paintings[15]. A few days after the outbreak of the war, it was no longer possible to send any rail transport to Warsaw. In his “Report on the Activities of Institutions and Civilian Defence of War”, a Polish military commander Juliusz Rommel wrote the following: “on September 8, that is when I arrived to Warsaw, it became clear for me that all railways – from the western border to the Vistula river, along with the considerable Warsaw junction – had already been immobilized and bombed. All stations were packed down with broken cars while train tracks were completely cluttered with damaged trains that had been abandoned by railway crews[16].”

The war deprived Felicja Herk-Lukanska of all her valuable possessions. As the result of the so-called September incidents, her belongings, along with 12 canvases and three sculptures, went missing “due to the German bombardment over Warsaw’s Main Railway Station while her luggage had been destroyed in a fire.” The first son of the victim died in the Dachau concentration camp in 1942 whereas her second son was killed in the Warsaw Uprising. After the fall of the revolt, her husband succumbed to lung disease. There were several cases of people who successfully managed to transport their property to Warsaw, even in spite of such heavy bombing. Before the war, a Warsaw-born woman, Helena Czechowska, lived with her husband Karol in Poznan. In September 1939, the widow of a soldier, killed on September 6, managed to relocate all her possessions to Warsaw and she settled in an apartment at the Old Town Square. The woman brought with her a large number of both art and collector’s items, including such paintings as “Mała trojka i wilki” [Little Troika and Wolves] by Józef Chełmoński – with a dedication of Countess Jeziorska – and “Dziewczyna wiejska” [Girl from the Countryside] by Leon Wyczółkowski[17].

Warsaw bridges and viaducts were bombarded to the same extent as the aforementioned railway stations. Three units of the anti-aircraft battery defended at the entrance to the Poniatowski Bridge from the side of the Washington Roundabout. German aircraft fiercely attacked the overpass, trying to kill its defenders. The tenements located in the immediate vicinity were most exposed to the damage caused by dive-bombers. And this is exactly how Alfred Birkenmayer, director of the Polish Radio, lost his eight-room apartment containing “a lot of antiques that been gathered over the years”, including 30 canvases, old Japanese engravings, relic porcelain from European manufactories as well as a collection of kilims. While developing his passion, Alfred Birkenmayer focused primarily on memorabilia related to the Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz. The collection included such pieces as 52 portraits and occasional pictures from the life of the writer as well as a few of his busts and portrait medallions. In his apartment, the art enthusiast kept first editions of Mickiewicz’s works that had been “partly removed from the rubble; nonetheless, they had been severely damaged, which constituted a terrible loss.” Following the first aircraft attack on the Poniatowski Bridge, Janina Nurzyńska, a woman who lived in the neighbourhood, decided to transfer some of her most valuable items (including a collection of 26 canvases) to a house at 3 May Avenue. She managed to place her pieces of art in a seemingly safe shelter at Nowy Świat Street, on the corner of Ordynacka Street. Unfortunately, the tenement located in the quarter was set on fire in September 1939, along with some of the canvases that had been previously deposited in the building[18].

On September 8, German motorized columns arrived to Warsaw from the direction of the Ochota district. Two days later, Wehrmacht troops managed to close the siege ring of the city from the side of Warsaw’s Praga district. Both German artillery fire as well as the bombing of Polish defensive positions ravaged the residential buildings located on the front line. The fire additionally powered the destruction of the houses at Grójecka Street while unburned apartments were plundered by German soldiers. Circumstances of the loss of priceless seventeenth-century documents, including grants, wills and heraldic agreements were described by Elzbieta Maliszewska, who resided at Grojecka[19] Street.

The residents sought to protect access to the city with streets barricades that had been built in a hurry. A great majority of such dams were made of wooden elements or even valuable household equipment. Both Polish soldiers as well as representatives of other services, involved in constructing fortifications and tank barriers in the Wola district, took from houses objects such as doors, tables and some other heavy pieces of furniture. As noted by Stefan Talikowski, a collector and antique enthusiast: “all these items could be found on the barricade built at Elektoralna Street. And as the fighting did not take place in this area, civilians removed the barricades right after the capitulation act had been signed, taking home the above-mentioned objects, also those that did not necessarily belong to them. Our caretaker managed to pick up the doors from the front apartment so that one half of them were missing; however, we could not find our Renaissance table that had previously stood in the living room. I conducted a private investigation, thanks to which I later determined where my table was[20].”

As a result of the September bombings, a valuable library owned by Wanda and Jan Rybiński was also destroyed to a large extent. The collection therein comprised about 500 books – such as incunables dating from the 15th to 19th century, including numerous examples of seventeenth-century Elzevirs in their original bindings. Previously, some items could be found in the library of Polish King Stanisław August Poniatowski. They mostly consisted of publications from the 18th century; they had leather bindings and contained engraved illustrations. The collection was rather of a bibliophilic nature; it contained both books originating from Napoleon’s library with bookplates and supralibros of Louis Philippe’s library. In addition, it encompassed first editions of numberless rare volumes, including Balzac’s works along with their original dedications. According to its owner, it was “a unique book collection – also in terms of its opulent bindings – that was burnt to a large extent in 1939 at Hoza Street while other prints, hidden in a building at Słupecka Street, were destroyed a few years later, during the Warsaw Uprising”.[21]

Warsaw residents particularly remember the date of September 25, 1939 – later referred to as “bloody Monday”. Polish politician Władysław Bartoszewski wrote the following: “after an all-night artillery fire in the capital, an aerial bombardment of an unprecedented intensity is taking place from 7 a.m. until dusk. Several hundred aircraft, arriving systematically in waves, dropped loads of demolition bombs as well as incendiary charges on the central district of Warsaw[22].” It was only on the same day that German Luftwaffe made 1,176 flights over the city. The city was bombarded by more than 400 airplanes: 240 Ju-87 B dive bombers, about 100 Dornier Do 17 light bombers, 30 Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft and Heinkle He 111 medium bombers. The city was bombarded by Luftwaffe aircraft; they dropped 560 tons of high explosive bombs and 72 tons of incendiary bombs. German air raids were mostly carried out in Warsaw’s city center, stretching along the Nowy Świat Street and Krakowskie Przedmieście Street as well as some other areas located near Świętokrzyska Street where Warsaw’s tallest buildings were located at that time (including the seat of the Polish Radio as well as the edifice of the telephone exchange). The city was on fire for 10 hours; from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.[23]

Zofia Peterson observed such frightening scenes of attempts made by Warsaw residents to save their property: “I could see something shocking on the corner of Lwowska Street. I have seen quite a lot of fires in my life; nonetheless, that one was terrible; a huge quadrangle almost wallowed in a deep sea of fire. Bright pillars of flames hit the sky from the doors as well as balcony windows. Sparks were falling from glowing or already black beams while the dark figures of the rescuers were hurrying amidst the black and orange – almost bloody – veils of fire. The pavement on the opposite side was covered with randomly piled equipment; when a blow of wind moved an ignited curtain, people started to throw some items on the street. Thus, the roadway was littered with linen, clothing and bundles. Cracking objects and the roar of the fire – all these sounds mixed up with deafening cacophony and desperate screams[24].”

While some residents decided to leave their apartments to fate, more industrious Varsovians made their best efforts to prevent fire from being set and then to spread to other places. Apart from demolition bombs as well as incendiary (phosphorus) charges dropped by Luftwaffe, nose-diving aircraft were cannonading civilians with on-board weapons. The act of destruction was concluded by German artillery. Valuable items were taken to the basements while pieces of furniture were purposely placed against walls. The windows were covered with boards or tapes so that the glass broken by an exploding bomb could not hurt people nor damage the apartment equipment. Inhabitants of the buildings removed all flammable fabrics and carpets and also scattered sand on the floors of rooms, next to the windows. In addition, they placed baskets filled with sand on the roofs of their houses; any fire could be rapidly put out if a bomb was immersed in such a box. Although little known during the September bombings, this method became more popular only a few years later, saving many tenement houses from total destruction during the Warsaw Uprising.

Warsaw, October 1948. Tenement houses destroyed during World War II in the area of the Old Town. No exact day of the event has yet been determined. © (PAP)

Warsaw, October 1948. Tenement houses destroyed during World War II in the area of the Old Town. No exact day of the event has yet been determined. © (PAP)The US historian Richard Pipes noted his impressions of the September 25 bombing in his journal: “A day-long air attack has begun […] while its scale has not been witnessed by anyone throughout the entire history of mankind. Numerous bombs kept falling on the defenseless city. Buildings of the capital rapidly became giant rubble, killing thousands of people and spreading a fire to the streets while hoards of people were wandering through rubble-covered street, holding their children and bundles with all their belongings. The German aviators – the worst beasts that have ever lived on the Earth – purposely descended the flight to hit the civilians with machine guns. Over the evening, the entire capital stood in flames, which seemed to resemble the Dante’s inferno[25].”

It was on the same day that Warsaw Water Filters were bombed, which resulted in a lack of water throughout the city. Located in a local neighbourhood, the villa of Władysław Woydyno’s family at Filtrowa Street was also completely destroyed. Woydyno recalled the event as following: “my apartment of a collector, expert, museum scientist, and educated painter, was filled with art works as well as antiques of museum importance; so many that it would take too much space to specify all of them and so renowned that are widely known by artists and historians from the National Museum and other institutions.” His valuable possessions were all destroyed including furniture, a book collection, not to mention paintings and artistic handicrafts. Nonetheless, Woydyno was most devastated by the destruction of his militaria collection. It included numerous ancient weapons: an old Persian gilt-repoussé helmet with drawings and inscriptions in silver and gold, a fifteenth-century Italian helmet, an engraved Italian half armor, two gold-engraved karabelas (a type of Polish sabre) and scabbards with an agate handle, a Turkish shotgun with a pattern-welded barrel (studded with rubies and turquoises), two ivory and silver-bound flintlocks, an Arab shotgun with the long stock and the barrel encrusted with silver and an engraved and gold-plated Arab inscription, a silver powder box of a Polish officer (dating from Napoleonic times), a sixteenth-century Italian rapier with an iron guard, a seventeenth-century Italian rapier with a brass guard as well as many other interesting items[26].

The walls of tenement houses, demolished by exploding bombs, revealed the interior of the buildings, which produced an extremely shocking sight. As reported by Mrs. Regulska: “We were met by the heat from burning houses at Pius Street [now Piękna Street], nearby Ujazdowskie Avenue. At the opposite side, the whole corner of a large house was completely torn off, as if it had been cut off, depicting the remnants of both apartments and furniture; on the fifth floor, one could notice horns of deer and goats, some paintings and a lamp on an oval wall; below, there was a china room and two chairs, placed systematically on both sides.” In her report, the author depicted the bold activity of the looters. They stole goods from deserted or half-demolished flats, as evidenced by the following record: “in the middle of the [Wiejska] Street, some two peasants were pushing an ordinary gardening wheelbarrows filled with crystal vases, a bronze candlestick as well as a tailcoat, shimmering with silk[27] tails.”

The tragic aftermath of September 25, when the Germans conducted a mass-scale attack on the capital, made the defenders aware of acts that can be performed by the aggressor as well as the means used to accomplish this goal. Thus, it can be assumed that the events of that day constituted a preview of the consequences of the Warsaw Uprising – the total destruction of both the city as well as its inhabitants. The events of this tragic day prompted Polish soldiers to make some difficult decisions. In a conversation with Colonel Wacław Lipinski, General Tadeusz Kutrzeba stated as following: “we no longer bind anything and anybody; we are only an island that does not await any relief because it will never happen, we are not able to change anything […]. And it was Warsaw and its inhabitants that were supposed to pay high price for such defense; they have to carry that horrible burden. Today’s events do not mean the end of the tragedy; the city will be razed to the ground and if any attack starts and the German break through our lines and enter the city, we will witness the slaughter[28].” Kutrzeba’s words aptly refer to the disaster experienced by the capital during the Warsaw Uprising only five years later. At the commanders’ briefing, summoned by General Rommel on September 26, the militaries decided to surrender. Such opinion was also maintained at the Citizens’ Committee – an institution representing the inhabitants of Warsaw. On Thursday, September 28, General Kutrzeba, delegated to talks with the German side, signed the capitulation treaty.

The balance of Warsaw’s losses in September 1939 constituted about 12 percent of the buildings destroyed within the city limits[29]. Around 10,000 inhabitants of the capital were killed while 50,000 were injured; also 6,000 Polish soldiers fell in battle and another 16,000 were wounded[30]. According to data collected at some police stations, out of 18,495 Warsaw tenements, only 2,645 were not damaged while as many as 13,843 residential buildings were completely ravaged by the occupier. Thus, destroyed houses account for 2,007 cases (14.3 percent). Interestingly, despite the fact that all territory of the capital was sieged by the German troops, also from the east, such districts located directly on the front line such as Mokotow, Ochota and Saska Kępa did not suffer the most severe losses; quite the contrary, it was the city center that experienced the biggest destruction: 44.2 percent of chambers of the 1st Police Station, located at Krakowskie Przedmieście, were dilapidated or ravaged; while the 10th Police Station at Ordynacka Street noted similar losses amounting to 43 percent[31]. Meanwhile, 41 percent of tenements in the Ochota district – most exposed to the artillery bombardment – were either swept away or damaged. As a result of the bombings, numerous buildings of particular importance for the culture and history of the city were destroyed and burned, including the Royal Castle, St. John’s Archcathedral, the Grand Theatre, the Warsaw Philharmonic, the building of the theatre (former edifice of the Golgotha panorama) at Karowa Street, the building of the Warsaw Stock Exchange at Karowa, as well as the palaces of Tepper, Primates, Branicki family, Bishops of Cracow and Małachowski family[32].

[1] S. Lorentz, Wspomnienie o ratowaniu zabytków i dzieł sztuki we wrześniu 1939 r. [On saving monuments and works of art in September 1939], In: Cywilna obrona Warszawy we wrześniu 1939 r. [Civil Defense of Warsaw in September 1939], Warsaw 1964, pp. 256–258.

[2] Ibidem, p. 263.

[3] Questionnaire of losses submitted by Tadeusz Bylewski to the Ministry of Culture and Art: Archiwum Akt Nowych, Ministerstwo Kultury i Sztuki (AAN, MKiS), microfilm (micr.), ref. number: B – 1173, p. 169.

[4] AAN, MKiS, ref. number mic. B-1173, p. 163–168; K. Estreicher, op.cit., p. 389; A. Tyczyńska, K. Znojewska “Straty wojenne. Malarstwo Polskie” [War Losses. Polish Painting], Poznań 1998, vol. 1, item 405, 418; A. Tyczyńska, K. Znojewska, “Straty wojenne. Malarstwo Polskie“, Poznan 2007, vol. 2, item 40, pp. 93, 95–97.

[5] S. Lorentz, op.cit., p. 272.

[6] State Archives of the Capital City of Warsaw, City Board of the Department of War Losses (APW ZM WSW), reference number 45, No. 3605, p. 511.

[7] Sławomir Bołdok, Antykwariaty artystyczne salony i domy aukcyjne [Antique Shops, Salons and Auction Houses], Warszawa 2004, pp. 138–139.

[8] W. Płachciński, Wspomnienia zbieracza [Collector’s Memoirs], a typescript created about 1942–44, APW, Zbiory rękopisów [Collection of manuscripts], ref. 300, p. 1.

[9] Ibidem.

[10] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 112, No. 20660, p. 701.

[11] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 127, No.1916, p. 729, appendix to the questionnaire, pp. 733–737v.

[12] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 91, No. 15268, p. 74; E. Chwalewik, Zbiory polskie. Archiwa, biblioteki, gabinety, galerie, muzea i inne zbiory pamiątek przeszłości w ojczyźnie i na obczyźnie w porządku alfabetycznym według miejscowości ułożone [Archives, libraries, offices, galleries, museums and other collections of souvenirs of the past in the homeland and abroad were arranged in an alphabetical order according to the village], Warsaw 1927, vol. 2, p. 407; K. Estreicher, op.cit., s. 395; A. Tyczynska, K. Znojewska, Straty Wojenne [War Losses], op.cit., vol. 1, items 39, 89, 134, 236.

[13] M. Emmerling, Luftwaffe nad Polską 1939 [Luftwaffe over Poland], vol. 2, Gdynia 2005, vol. 2, p. 83.

[14] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 117, No. 21779, p. 109.

[15] APW, ZM WSW, ref. number 79, No. 12469, p. 874. In 1945, a questionnaire on war losses of Krystyna Kinga and Andrzej Grzegorz Gora was submitted to the Department of War Losses. When the Second World War broke out, the siblings were only couple of years old. The document was filled out by Zofia Orlanska; after the war, the woman took care of the children of her niece, Antonina Gorzyna (née Gabszewicz). Before the war, Andrzej Gora, father and lawyer, belonged to the management of the Tyniec steelworks in the Zaolzie region. He was executed on November 12, 1943 in Warsaw. Antonina Gorzyna, mother and owner of the guesthouse at Zlota Street in Warsaw, was killed in Auschwitz on December 30, 1943. Gora family’s possessions were partially confiscated by the German occupier on the occasion of the detainment of the parents in October 1943. Both the guesthouse and the flat at Zlota Street were burned during the Warsaw Uprising.

[16] J. Rómmel, Relacja o działalności instytucji i agend cywilnej obrony Warszawy [Report on the activities of the institutions and agencies of the civil defense of Warsaw], No. 25, In: Cywilna Obrona Warszawy [Civil Defense of Warsaw]…, op.cit., p. 370.

[17] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 41, No. 2588, p. 392, appendix to the questionnaire, p. 396v.

[18] APW, ZM WSW, ref. number 47, No. 4091, p. 500. During the Warsaw Uprising, Janina Nurzynska’s house, located at 3 May Avenue, was bombed; the woman wrote: “my apartment turned into a bunker; everything was looted while the rest was shattered by bullets.”

[19] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 180, No. 3284, p. 351. The woman was a chemical engineer and worked as an assistant at the Warsaw School of Technology.

[20] National Library (BN), S. Talikowski, microfilm, ref. akc. 11061, p. 393.

[21] APW, ZM WSW, reference number52, No. 5286, appendix to the questionnaire, p. 163.

[22] W. Bartoszewski, Warszawa w kampanii wrześniowej, kronika ważniejszych wydarzeń [Warsaw during the September Campaign: Chronicle of Major Events], In: Cywilna Obrona…, op.cit., p. XXIV.

[23] M. Cieplewicz, E. Kozłowski, Obrona Warszawy 1939 we wspomnieniach [Defense of Warsaw in 1939: Memoirs], Warsaw 1984.

[24] BN, Z. Petersowa, Piekło i ludzie [People and Hell], microfilm, ref. 6405, pp. 32–36.

[25] R. Pipes, Żyłem Wspomnienia niezależnego [VIXI – Memoirs of a Non-Belonger], Warsaw 2005, p. 5.

[26] APW, ZM WSW, reference number 90, pp. 15041, p. 195.

[27] BN, Z. Petersowa, op.cit., p. 33.

[28] W. Lipiński, Dziennik, Wrześniowa obrona Warszawy 1939 roku [A Journal. Defending Warsaw in September 1939], ed. J.M. Kłoczowski, Warsaw 1989, pp. 139–140.

[29] In total, 7 percent of residential room were completely ravaged while 17 percent [of the ones that survived] were damaged – see “Warsawa w liczbach” [Warsaw in Numbers] (1947); op.cit., pp, 21, 28 and “Warszawa w liczbach” (1948), op.cit., p. 30.

[30] T. Szarota, Naloty na Warszawę podczas II wojny światowej [Air Raids on Warsaw during the Second World War], In: W. Fałkowski, op.cit., p. 263. This material was found by the author of the following article in the group of files of the Government Delegation for Poland, Archiwum Art Nowych [Archive of Modern Records], 6th division, ref. number 202 / I-43, vol. I, k. 6–10.

[31] “Warszawa w liczbach” [Warsaw in Numbers] (1947); op.cit., pp, 21, 28 and “Warszawa w liczbach” (1948), op.cit., p. 30.

[32] J. Majewski, Śródmieście i jego mieszkańcy w latach niemieckiej okupacji: październik 1939 –

1 sierpnia 1944. Dzień powszedni [Warsaw’s City Centre and Its Inhabitants Under the German Occupation: October 1939 – August 1, 1944. An Ordinary Day], In: W. Fałkowski, op.cit., pp. 66–68.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.