THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 1 March 2018 Author: Piotr Kościński

Poland and Ukraine: History Divides

Although Polish-Ukrainian relations are more than just good, unfortunately, they have recently found themselves in the shadow of a difficult history between the two nations. In Central and Eastern Europe, history still plays a very important role, and often has a dominant influence on political relations.

Trade between Poland and Ukraine is developing rapidly. In 2017, Polish exports to Ukraine grew by 25 percent. Polish investments in Ukraine are gradually expanding (close to $800 million). Also, Ukrainians are setting up their companies in Poland, mainly in the commercial and service industries (transportation, gastronomy, construction).[1] In contrast, a very large group of Ukrainians have found employment in Poland (the number is estimated at two million people), although most of them do not come here permanently, but only temporarily — so the rotation of Ukrainian employees is high. It has been forecast that this number may increase to three million.[2] In some cities, the percentage of Ukrainian workers is significant, for example in Wrocław, a large city and the capital of Lower Silesia, there are as many as 64,000 Ukrainians, or about ten percent of the city’s population.[3] Generally, Poles are very positively inclined towards the Ukrainians. The media only rarely reports cases of negative treatment of Ukrainians, and the same goes as far as crime by Ukrainians — it is not substantial.

What is more, Poland still enjoys sympathy among Ukrainians — according to the latest research by the American think tank IRI, 58 percent of Ukrainians have a positive or very positive attitude towards Poland, while just over one percent have a negative attitude; the European Union as a whole trails Poland (54 percent to six percent) as does Belarus (52 percent to one percent), followed by Canada, Germany and Lithuania.[4] Meanwhile, presidents, prime ministers or ministers of both countries talk primarily about the difficult problems of common history, and parliaments adopt special laws or resolutions on these matters.

A Complicated 20th Century

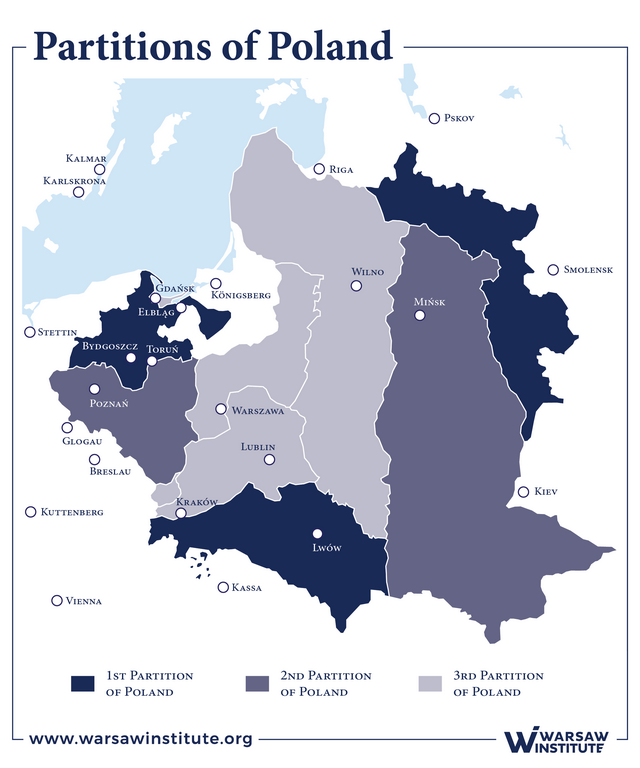

After the end of the First World War, the balance of power in Europe changed, with the fall of empires, including the German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, which in the eighteenth century had partitioned Poland (also known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth). Thus, Poland was reborn, and its leaders sought to regain the former pre-partition state borders. So, they aspired to acquire some of the areas from which the Ukrainians wanted to create their state. In 1918, it was impossible to delineate a clear border separating Poles from Ukrainians. The best example is the city of Lviv (earlier Lwów), where before the Second World War most of the inhabitants were Poles, but mainly Ukrainians lived in the surrounding villages.

In November 1918, Ukrainian-Polish battles for Lwów began. Poland was fighting against the newly-created West Ukrainian People’s Republic. The Ukrainians lost and in July 1919, the entire area of so-called Eastern Galicia (previously belonging to the Austro-Hungarian Empire) found itself in Polish hands. In 1923, the Council of Ambassadors[5] recognized the sovereignty of Poland over this territory. Three provinces were created there: Lwów, where Poles accounted for 57 percent, and Ukrainians 34 percent, Stanisławów — 22 percent Poles and 69 percent Ukrainians, and Tarnopol — 49 percent Poles and 46 percent Ukrainians. The Volhynia Province (belonging to the Russian Empire during the First World War) was also nationally mixed, with only 17 percent Poles, and 69 percent Ukrainians.

The policies of Polish authorities towards Ukrainians varied. It was not always characterized by favor or even indifference. There were periods of calm, but anti-Ukrainian repressions also took place, including the limitation of the functioning of Ukrainian schools, institutions and organizations. In retaliation, radical Ukrainian nationalists organized terrorist actions. The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), supported and financed by the USSR, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Germany, carried out bloody attacks. In 1931, Tadeusz Hołówka, a deputy to the Sejm, was assassinated, and in 1934, the Minister of Internal Affairs, Bronisław Pieracki, was also murdered. From 1921 to 1939, a total of 36 Ukrainians, 25 Poles, one Russian and one Jew died at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists.[6]

UPA as Heroes

During World War II, the nationalists formed the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in 1942. The UPA leadership decided to eliminate the Poles living in Volhynia. According to Polish historians, starting in 1943, UPA guerrillas murdered up to 100,000 Poles, mainly civilians (including in Eastern Galicia). The Poles responded with force, killing at least several thousand Ukrainians.[7] But the UPA also fought against the Soviets;[8] its units effectively engaged with the Red Army and the NKVD until the 1950s, based in forest hideouts. The Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) gives April 12, 1960, as the date of their last battle, 15 years after the end of the war. In this way, the UPA and its leader, Stepan Bandera, became a symbol of anti-Communism in Ukraine and thus took an extremely important place in the historical policy of today’s Ukraine, which is still struggling with Russian influence. In the twentieth century there were many significant Ukrainian activists and organizations, some cooperating with Poland, but the large-scale armed struggle — with the Soviets no less — was mainly led by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

The leader of the OUN and the spiritual patron of UPA, Stepan Bandera, who was murdered in Germany by a Soviet agent in 1959, is today put on monuments in Ukraine, and numerous streets are named after him. The case is similar for UPA, which has become the patron of several dozen streets in various Ukrainian cities. For Poles it is almost impossible to accept, because before 1939, Poland was enemy number one to Bandera. He took part in organizing the aforementioned attack on the interior minister, for which he was sentenced to death (commuted to life imprisonment).

In Poland, non-governmental organizations with the consent of local authorities dismantled an illegal monument in honor of the UPA in the small town of Hruszowice in the east of the country. In response, the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance halted the exhumation of Polish victims in Volhynia. This caused outrage on the Polish side, which saw innocent people being deprived of the right to a proper burial. These factors, which have accumulated to the conflict since the end of World War II, led to one of the amendments to the Polish Institute of National Remembrance Act,[9] introduced into the Polish Parliament by the small nationalist party Kukiz ’15. This Act refers to documenting and prosecuting crimes committed against Poles (meaning “ethnic Poles”, and therefore not necessarily citizens of the Republic of Poland) and Polish citizens (not necessarily of Polish ethnicity — including Jews) and political repressions in 1917–1990. Up to now, there has been talk of two types of crimes: Nazi and Communist. The amendment also specifically references the crimes of “Ukrainian nationalists and members of Ukrainian organizations collaborating with the German Third Reich”. In this way, Ukrainians became the only nation mentioned in the Act.

The Ukrainians reacted very critically to the adoption of the law. The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted a resolution in which it stated that it “categorically refuses and rejects the policy of double standards and imposing the idea of collective responsibility and attempts by the Polish side to equate all the fighters for Ukraine’s independence with the crimes of two totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century, Nazi and communist.”

An Act to Review

We already know that the Polish law was formulated incorrectly. First of all, in Ukrainian, “nationalism” has a slightly different meaning than in Polish, though the languages are very similar. Ukrainian Wikipedia defines “nationalism” as an ideology and a socio-political movement “aiming at the creation and development of a Ukrainian, independent state”,[10] and thus something that we would call an independence ideology. In contrast, the concept of a “radical-nationalist” movement is closer to the Polish concept of nationalism. While the OUN was guided by a specific “integral nationalism” that is some type of fascism

Secondly, the range of years 1925–1950 was used incorrectly. The period 1925–1939 was a time when the Polish state existed, the justice system and the police were functioning, and numerous Ukrainian activists were arrested and convicted (including Stepan Bandera, who was released from prison during the German invasion in September 1939). In 1945–1950, the Polish state operated under the control of the USSR, and a policy pursued by the communist regime was the prosecution of UPA guerrillas, as well as the notorious Operation Vistula in 1947, consisting of the forced resettlement of all Ukrainian populations from areas located to the southeast of Bieszczady Mountains to the areas taken over from Germany in the north and west.

These were the circumstances when the President of Poland Andrzej Duda referred the Institute of National Remembrance Act to the Constitutional Tribunal.[11] First and foremost he appealed against provisions containing the wording “Ukrainian nationalists” and “Eastern Lesser Poland.” The last term was used by Poles to define Eastern Galicia before World War II, which today belongs to Ukraine; according to some Ukrainians, calling it “Lesser Poland” (Małopolska) could be a manifestation of Polish territorial claims, although in fact there is no such thing.

Nevertheless, the proceedings relating to the IPN Act have inflamed Polish-Ukrainian relations in historical matters. The talks conducted in February 2018 between the deputy prime ministers of Poland and Ukraine — Piotr Gliński and Pavlo Rozenka — did not bring any results. At first, the Polish reaction was restrained, but later an official communique from Minister Krzysztof Szczerski was released: “The Chancellery of the President of the Republic of Poland is deeply disappointed by the results of talks between the deputy prime ministers of Ukraine and Poland.” It continued that “the lack of a decision from the Ukrainian side on the fundamental issue of lifting the ban on Polish exhumations on the territory of Ukraine indicates a serious decline in trust”.[12]

Not Everyone Lives in the Past

Unfortunately, the Polish-Ukrainian historical conflict can be expected to intensify. Judging from the exchange of opinions on social networks, especially on Facebook, the subject of the dispute will not only be World War II, but also the interwar period between World War I and II, and even the time of the so-called First Republic of Poland, i.e. before the partitions of Poland, until the end of the 18th century. This does not bode well for the future. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that ordinary citizens are not particularly concerned about this. In Lviv, on the centrally located Svobody Prospekt, one of the old buildings has the inscription in Polish: Galicyjska Kasa Oszczędnośi (Galician Savings Bank). This inscription was painted over through the years, and it has appeared again. Finally, it was restored. Several Polish inscriptions on the walls of the houses have also been restored on the Old Market Square. No one is surprised by the pictures of pre-war Lwów in cafes, just as it is perfectly understandable that in restaurants there are Polish menus alongside Ukrainian ones — tourists from Poland are numerous there. All of this raises hopes that the historical conflict will not prevent normal cooperation between the two countries, and that history will not dominate over the issues that people on both sides of the border live with on a daily basis.

[1] E. Bodio, ”Polskie firmy z nadzieją patrzą na Ukrainę”, Rzeczpospolita, February 21, 2018, http://www.rp.pl/Biznes/302219959-RZECZoBIZNESIE-Elzbieta-Bodio-Polskie-firmy-z-nadzieja-patrza-na-Ukraine.html [Retrieved February 25, 2018].

[2] M. Lis, “Za rok w Polsce będzie pracować 3 mln Ukraińców. Ich pensje rosną szybciej niż przeciętne”, Money.pl, October 25, 2017, https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/unia-europejska/wiadomosci/artykul/ukraincy-pracujacy-w-polsce-pensja-liczba,118,0,2381430.html [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[3] B. Organisty, “Co dziesiąty mieszkaniec Wrocławia to Ukrainiec. Są tu bardziej niż mile widziani”, Gazeta Wrocławska, April 19, 2017, http://www.gazetawroclawska.pl/wiadomosci/a/co-dziesiaty-mieszkaniec-wroclawia-to-ukrainiec-sa-tu-bardziej-niz-mile-widziani,11999288/ [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[4] Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine, June 9 – July 7, 2017, http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/2017-8-22_ukraine_poll-four_oversamples.pdf [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[5] The Conference of Ambassadors of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers, founded in Paris in January 1920, successor to the Supreme War Council.

[6] OUN-UPA, Istoriya http://oun-upa.national.org.ua/history/ [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[7] 1943 Volhynia Massacre, Truth and Remembrace, http://volhyniamassacre.eu/ [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[8] Ukrainska Powstanska Armia, UINP, http://www.memory.gov.ua/page/ukrainska-povstanska-armiya [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[9] USTAWA z dnia 18 grudnia 1998 r. o Instytucie Pamięci Narodowej – Komisji Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu https://ipn.gov.pl/pl/o-ipn/ustawa/24216,Ustawa.html [Retrieved June 30, 2018].

[10] Ukrajinskyj Nacjonalizm, Wikipedia, https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/Націоналізм [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[11] Nowelizacja ustawy o IPN skierowana do Trybunału Konstytucyjnego, http://www.prezydent.pl/prawo/ustawy/odeslane-do-tk/art,6,nowelizacja-ustawy-o-ipn-skierowana-do-trybunalu-konstytucyjnego.html [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

[12] Oświadczenie Kancelarii Prezydenta RP, February 17, 2018, http://www.prezydent.pl/kancelaria/dzialalnosc-kancelarii/art,58,oswiadczenie-kancelarii-prezydenta-rp-.html [Retrieved: February 25, 2018].

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.