THE WARSAW INSTITUTE REVIEW

Date: 12 March 2018 Author: Grzegorz Kuczyński

Estonian Spy Hunters

Western intelligence services have been paying special attention to increasing Russian espionage activity in recent years, which has reached Cold War levels. NATO’s eastern flank is particularly vulnerable to Moscow’s efforts.

The former Eastern Bloc countries and the former republics of the Soviet Union are dealing with this with varying degrees of effectiveness. Undoubtedly one of the most active sections of this front in the secret war is Estonia, both due to its location and the legacy of the Soviet occupation, such as a substantial Russian minority. These difficult conditions have not prevented the Estonians from building an effective counterintelligence apparatus. Perhaps in no other NATO member state are Russian spies caught as often.

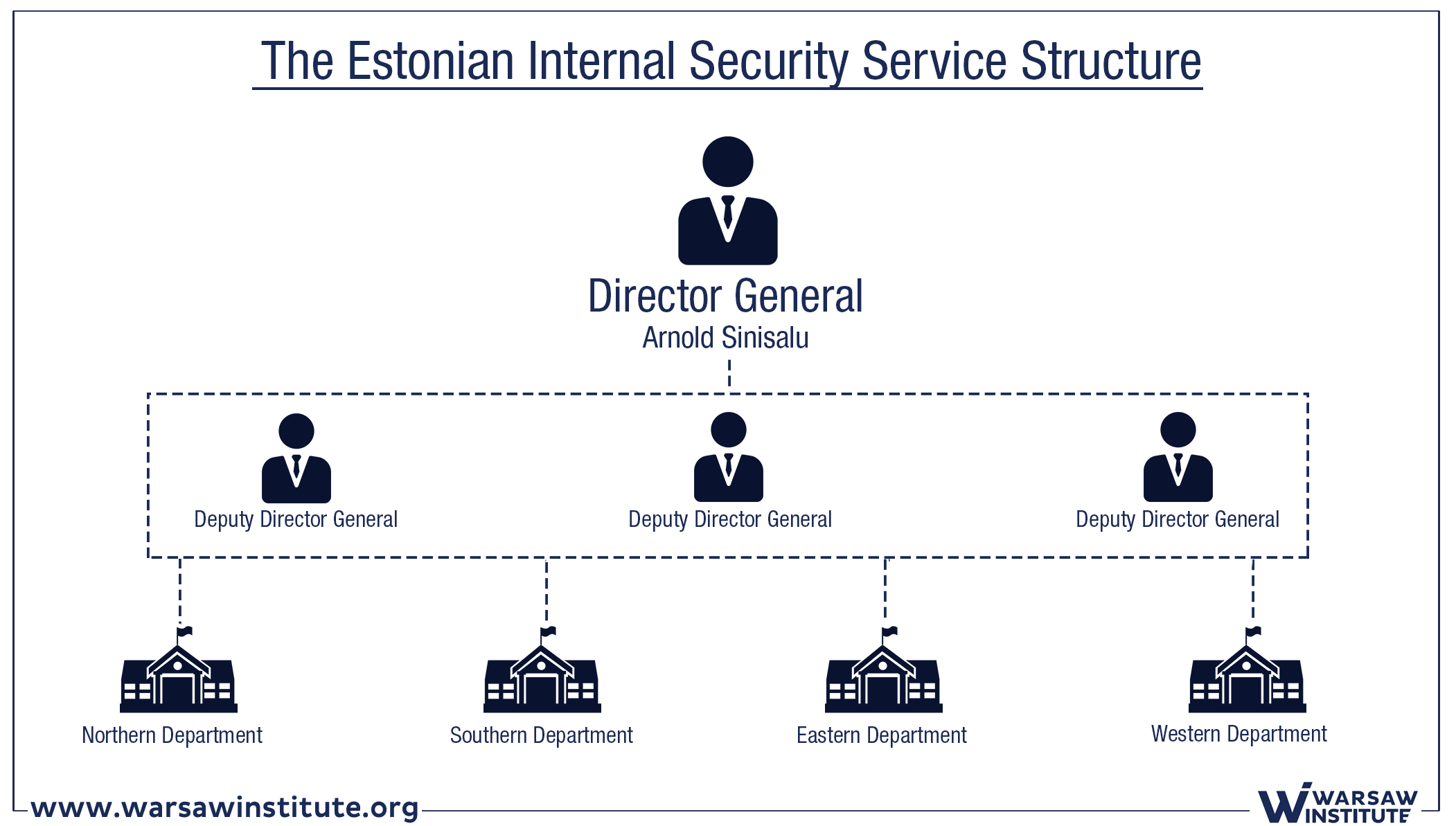

The Estonian Internal Security Service (Kaitsepolitseiamet – KaPo) is an intelligence service considered one of the best and most resistant to Russian infiltration in the former Eastern Bloc. The Russians themselves admit this, as the Estonian service has for years been one of their most difficult opponents in Europe. In the 1990s the KaPo already became a strategic partner of British intelligence. This was one of the reasons why Vasili Mitrokhin came to the British Isles via Estonia with his precious KGB archive instead of crossing the Atlantic.

Over the last decade in Estonia, there have been several high-profile apprehensions of spies, including people working for the KaPo. The case of Herman Simm was especially important, as it struck at not only the security of Estonia, but the whole of NATO. Catching a Russian spy in its own ranks was a great success for KaPo. The case of Aleksei Dressen, detailed later in this article, shows that the extreme limitation of trust principle must apply to Estonians all the time and everywhere – it is unknown whether there are more “sleepers” like this. The case of Vladimir Veitman, also detailed later, demonstrates that the burden of the Soviet past remains a problem for the agencies themselves.

Since 2014 – probably in connection with the rapid increase in the Russian threat– Estonians are dealing with hostile agents very firmly. In the case of higher-level spies, the KaPo can build a case, gather intelligence and adjust operations accordingly over a longer timeframe. On the other hand, lower level informants, without access to state secrets, and not holding important positions, but mainly dealing with observation, are quickly stopped by the Estonians, put in jail and the fact is publicly broadcast. This demonstrates the increased vigilance of the Estonian side, which knows perfectly well that a tough attitude is best in relation to Moscow.

As said by John Schindler, a former U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) analyst, “The Estonians have dealt with the Russians, and before them the Soviets, for so long, they intuitively understand Russian intelligence culture and how they operate.”[1] Estonians do not hush up nor minimize the cases of detained and deported Russian spies. In the annual report on state security (“Aastaraamat”) issued since 1998, the Kaitsepolitsei exposes Russia’s operating methods, naming people and organizations (and showing photos) of those suspected of contacts with Russian intelligence. This detailed report on the operation of the agency was the first publication of its kind in the world. The fact that Estonia has one of the best services in the East is attested to by its effective information warfare; not just in regards to making espionage cases public, but also the severity of justice: spies usually get the maximum penalty.

The KaPo vs. Heirs to the KGB

Estonian counterintelligence is said to be one of the most effective in NATO, begging the question as to the reasons for his effectiveness. Starting from square one, using extreme vetting as well as the de-Sovietization of the security apparatus certainly helped. It could have gone differently – which can be seen in the history of the activities of the main Russian agent of influence in Estonia, Edgar Savisaar. When he became the prime minister of the Estonian Socialist Soviet Republic (ESRR) in 1990, he created a special agency (Eriteenistus) independent of the Soviets, drawing on former officers of the Ministry of the Interior of the ESRR. When Estonia regained its independence, Savisaar automatically became the prime minister of the Republic of Estonia. In 1991, the Kaitsepolitsei (Security Police) was created, as a completely new special agency, independent of the Estonian KGB, and harkening back to pre-war traditions. However, Savisaar did not subordinate it to Eriteenistus, and even began to staff it with former KGB officers. In January 1992, Savisaar lost the post of prime minister, and Eriteenistus was dissolved. A few years later, drawing on former personnel, Savisaar created a private security agency SIA, which – as the head of the Ministry of the Interior – he used for surveillance of members of the government, including the president.

When Estonia regained its independence, the authorities recognized former officers of the Soviet intelligence services and the Baltic Military District as one of their main problems. This was especially important in creating a new counterintelligence service. Later, some of them worked and served in the institutions of the independent Estonia. The only specialists in the country on technical information gathering techniques (wiretaps, etc.) had previously worked in the KGB. The KaPo leadership decided to reach out to them until they could train new experts. They included just about a dozen people, who were kept away from planning and managing operations. Even so, after many years it turned out that most of this group had ties with Russian intelligence. This shows that the special law adopted in 1995 to minimize the risks associated with former KGB agents could not fully solve this problem. “The law on the procedure of registration and disclosure of persons who served in the intelligence or counterintelligence services or armed forces of countries that occupied Europe, or cooperated with these organizations” led to many former Soviet security agents revealing the fact of their cooperation with the KGB, in exchange for immunity and anonymity. This seriously hampered Russia’s contact with them, although it did not completely eliminate the possibility. In each of the infamous espionage scandals of recent years, the FSB or SVR officers supervising or recruiting agents in Estonia, turned out to be former KGB employees of the Republic (e.g. Herman Simm and Vladimir Veitman were supervised by Valeri Zentsov and Nikolai Yermakov).

Activities on Estonian territory and against Estonia are carried out by all three of Russia’s most important secret services: the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), the Federal Security Service (FSB), and the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU). Although the GRU coordinates espionage activities in the security sphere, the FSB is also active in this area, primarily on the border zone and at the informant level. They mainly recruited from smugglers and Russian-speaking Estonian residents who often travel to visit family in Russia. Vladimir Putin’s presidential decree of June 17, 2007, allowed Russians living in Estonia and Latvia to visit Russia without a visa. As a result, people with a Russian passport or a stateless person in Estonia can travel around both the EU and Russia without a visa, while citizens of Estonia must apply for a paid visa.

A popular recruitment method used by the FSB is to enlist people who have connections with criminal circles. Illegal crossing of the border by such persons, if only for smuggling, makes them an easy target. Insufficient control over the land border with Russia is one of the biggest weak points for Estonian counterintelligence. Most of this border runs through densely forested, hilly areas. Illegal crossings are not difficult, especially since the location of surveillance cameras is well-known to the Russians.

In turn, the SVR controls more valuable agents, often located in institutions with the possibility of access to state secrets. Economic espionage is also a significant activity. However, all three services are interested in NATO activities in Estonia, for example, allied troops residing in the country or occasional multinational exercises. Moscow is especially interested in the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. Estonia’s foreign and security policy, defense planning, mutual allied cooperation, development of armed forces, defense industry, armaments and introduction of new technologies are of course subjects of interest to the Russians. Moscow is not only interested in the Estonian army, but also sees a threat in the paramilitary Estonian Defence League (Kaitseliit), Estonia’s territorial self-defense force. The Russians also gather up all possible information about infrastructure. It is known that Russian diplomats catalogue and detail all the bridges in southern Estonia lying on the east-west line. Their focus is upon structures along the expressway connecting the Russian border with the Baltic Sea and the strategic railway line.

The Russians carry out spying activities against Estonia, both from their own territory and from diplomatic missions. The centers that coordinate spy activity are the embassy in Tallinn and the general consulates in Tartu and Narva. Roughly one-third of diplomats are suspected to be intelligence officers. What distinguishes the activities of Russian “diplomats” in Estonia (and Lithuania and Latvia) from the activity of their colleagues in Poland, for example, is that they not only collect valuable data for Moscow, but also conduct subversive activities directed against the authorities. However, as noted in recent KaPo reports, the nature of the agents’ cover is changing. Diplomatic status is increasingly rare, while more and more often they are illegals operating in the country or agents operating under the cover of being businessmen and journalists. Due to Moscow’s wariness of Estonian counterintelligence, Russian case officers usually meet their informants in third countries.

GRU

In January 2017, the Estonian service stopped a GRU employee. This was the first case in the modern history of the Baltic States that a Russian military intelligence officer was captured. It is known that he is a Russian citizen, though this says little as to whether he lived permanently in Estonia. He was convicted of spying and sentenced in May 2017 to five years in prison.

For the GRU, Estonia is the “gateway” to NATO and knowledge about the whole alliance, as Allied troops are located and international exercises are conducted there.

“The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre is one of the main objects of interest for our intelligence services in Estonia. We are also interested in NATO’s defense plans for the Baltic region in the event of a deterioration of Russia’s relations with the alliance, in the event of military action. Since the Estonians have been strongly integrated with the NATO intelligence community and are one of its active participants, they have learned modern methods of work and conducting operations against Russia, so this information is of great importance to us,” wrote Mikhail Aleksandrov, Director of the Baltic Department at the Institute of the Commonwealth of Independent States in Russia, in the pages of Kommersanta, August 2013.

Russian intelligence activity is particularly intensive during large NATO exercises conducted within Estonia. The GRU then not only uses human intelligence (HUMINT), but also, for example, extensively deploys Spetsnaz (special forces) drones. Many of these short-range, unmanned aerial vehicles, equipped with cameras, appeared in the Estonian sky in April 2015 during the Trident Jaguar joint-exercise. A year earlier, during NATO special forces training in the same region, the Russians activated two “telephone spectrum-towers”, with the help of which they obtained the IMEI numbers NATO soldiers’ phones in the area of the exercises. Having such data makes possible the monitoring of special forces personnel movements. The headquarters of the aforementioned special forces exercises was located in the Eametsa base near Pärnu. This is one of the three Estonian military facilities of greatest interest to Russia, aside from Vovu and Ämari (NATO planes are stationed there). In 2016 alone, Estonian counterintelligence recorded eleven suspect incidents there; these generally involved suspiciously slow-moving cars and cases of people video recording from the outside and taking pictures of the base and its personnel. About ten kilometers east of Eametsa lies the village of Sindi. This village is mostly inhabited by Russians. The Kaitsepolitsei knows that that among them are people cooperating with Moscow.

FSB

The Federal Security Service, a counterintelligence organization was given the right to conduct foreign operations under Putin’s rule. However it has traditionally focused on the border area (the FSB controls the border protection forces, as was the case with the KGB during the Soviet era) and the entire post-Soviet sphere. Border guards run so-called “shallow intel” on the Estonian side of the border. Activities against Estonia are handled by the FSB district departments in Pskov and St. Petersburg, although the most important operations (such as the kidnapping of KaPo officer Eston Kohver in 2014) involve Moscow headquarters. In early 2007, Colonel Andrei Lobanov of the St. Petersburg FSB is known to have taken several attempts to recruit Estonian citizens. Soon after, there were turbulent street riots stoked by Russian radicals under the pretext of defending the monument to Soviet soldiers in Tallinn. The Kaitsepolitsei did not obtain evidence that Russian intelligence directly steered this operation (although they were responsible for a cyber-attack on Estonia that coincided with the riots). That said, it is known that intelligence officer-diplomats met secretly with Russian activists. It is also known that in Estonia at that time (April 30 – May 1) a delegation of the Duma (lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia) made a pre-planned visit. Among its members was Nikolay Kovalyov, former director of the FSB. He gave local Russian activists detailed plans for the area around the monument, with the locations of deployed police units.

The FSB is interested in virtually everything in Estonia, from its internal policy and security apparatus to foreign policy and the military. Not only are officials and agents targets, but so are journalists and businessmen. The FSB tries to recruit agents among Estonian residents who visit Russia (so-called “territorial intelligence”). It is faster and easier to identify and then recruit someone on your own territory, especially if such a person happens to break the law in Russia. The FSB then has the option of discreet access to such a person, forcing them to cooperate through blackmail. The high-risk group, from the point of view of the KaPo, are Russian-speaking residents on the border areas who often travel to Russia.

According to official data from Estonian authorities, in 2015–2016 alone, five FSB spies, residents of Estonia, were arrested and sentenced to prison. Three have dual citizenship (Estonian and Russian), one only an Estonian passport, and one is stateless. None of them are ethnic Estonians. In a matter of months, they were all swiftly sentenced to several years in prison.

Arrested in March 2015, Aleksandr Rudnev, a dual citizen, had worked for the FSB since 2013. In exchange for money, he collected information on the Estonian army and its NATO allies. He was interested in unit movements, the situation in the bases, and equipment. He took photos and made videos, and then showed them to his handlers. Rudnev was also interested in everything related to border protection. He collected and transmitted information on border guard posts and officers from the Southern Prefectural Police and Border Guard (in Estonia, the police and border guards are one institution). In October 2015, Rudnev was convicted by the Tartu district court to two years in prison under paragraph 2351 of the Criminal Code (“conspiracy against the Republic of Estonia”). That same month, the KaPo apprehended another spy, Maksim Gruzdev. This citizen of Estonia, like Rudnev, started cooperating with the FSB in 2013, he signed a commitment to cooperate in the second half of that year in the Pskov Oblast which borders Estonia. Gruzdev reported on the staff and activities of the Estonian security and investigative agencies. His espionage activity also included the KaPo. He was sentenced to four years in prison in February 2016 by the Tartu District Court, also under paragraph 2351.

Stopped in 2015, Pawel Romanov had a much longer spying career than Gruzdev and Rudnev. This Russian living in Estonia was a stateless person. He was recruited by the Russian Federal Counterintelligence Service (FSK) in 1994 (the FSK later transformed into the FSB). Romanov was an experienced smuggler, and thus an invaluable source of knowledge for the Russians on the illegal crossing of the Estonian-Russian border. He collected information about the border guard posts and their personnel, responsibilities, methods of operation and borderland tactics in the south of Estonia. Thanks to this agent, the Russians knew the location of surveillance cameras in the forested sections of the border. It is also known that the FSB received information from Romanov about military installations in southern Estonia. The district court in Tartu sentenced Romanov to four years and 10 months in prison for “non-violent acts committed by a foreigner against the Republic of Estonia” (paragraph 233 of the Criminal Code).

According to the information provided by the KaPo, two more FSB agents were detained and sentenced in 2016, both of whom were dual citizens and had spied for money. Artyom Malyshev was recruited by Russian intelligence in 2011. He provided information on the activities of the Estonian army and its allies, on the movement of military equipment and border posts. He was convicted under the aforementioned paragraph 2351, to two and a half years in prison. Alik Chuczbarow had worked for the FSB since 2012. He provided information about the activities of the border guards at the Piusa post. He was given a total of three years in prison.

FSB spying activity in Estonia, however, does not just include small-scale smugglers. On November 4, 2017, during an attempt to cross the border on the bridge in Narva, the KaPo stopped Alexei Vasilyev, a Russian citizen studying in Estonia. Two days later, he heard the official allegations against him of espionage activity (paragraph 233 of the Criminal Code) and cybercriminal activity (paragraph 2016/1) and so upon the decision of the court was placed in pre-trial detention. Vasilyev was just 20 years old and came from the village of Kingisepp in the Leningrad district, located near the border. He graduated from elementary school there, then moved to high school in Sillamäe in Estonia, where he learned computer programming. After three years he went to Russia for a period of time, officially for work, but most likely it’s then that he underwent training in the FSB. Already in the summer of 2017, he returned to Estonia, to Kohtla-Järve, to a branch of the Tallinn University of Technology, majoring in computer and systems engineering.

The Dressen Case

On February 22, 2012 at Tallinn airport, counterintelligence officers detained Aleksei and Viktoria Dressen. The woman, who boarded a plane flying to Moscow, had secret materials on a memory stick which she had received moments earlier in the departures hall from her husband. Prior to 1991, Aleksei Dressen worked in the militia, where he was most likely contacted by the KGB, and contacts were renewed years later by the FSB. In 1993, Dressen moved from the police to the KaPo. For over a decade, he worked in the department fighting economic crime. The FSB recruited him as a result of a long-term operation (1998–2001). The Russians took advantage of the fact that Dressen vacationed with relatives of his wife in Russia. He began to actively cooperate with the FSB in 2007 – at the time changing his profile and beginning to deal in the KaPo with the investigation of extremists, including Russians. Dressen worked for the FSB Counterintelligence Board (DKRO), the cell carrying out operations aimed at the security services of other countries. The main roles in recruiting and then supervising him were played by two FSB officers: Major General Evgeny Tiazkun and Colonel Mikhail Loginov. Dressen usually met with his case officer in exotic countries where he vacationed. From 2002 to 2009, these were in order: Cyprus, Turkey, Tunisia, Malaysia, the Dominican Republic and Morocco. Dressen was also initially in Moscow, but only until the transition to his activities against extremists. From then on, like many of his colleagues at the KaPo, he was formally banned from traveling to Russia. His wife Viktoria took on the role of courier. Under the guise of business activities, she often traveled to Moscow. The Dressens worked for the FSB for money. However, they masked themselves very well, as they did not flaunt their wealth, but hoarded it. During the search of the Dressen home, investigators found 20,000 euros hidden in cash.

It is difficult to assess the true scale of damage to Estonia’s security caused by the Dressen’s activities. The Russians certainly obtained extensive knowledge of the KaPo’s actions towards Russian radicals. But did the traitor in the ranks of Estonian counterintelligence give Moscow something more? The mere fact that the Russians picked him in exchange for the kidnapped and convicted KaPo officer Eston Kohver, suggests that Dressen was a very valuable agent for the FSB. It is worth paying attention to the information that the state press agency Interfax conveyed on the occasion of this exchange. It cited an anonymous source from Russian intelligence, who said that in the 1990s Dressen worked for Russian counterintelligence, obtaining information on the intelligence operations of the United States and Great Britain in the Baltic States, specifically: “For 20 years in the Estonian special services, Dressen obtained and handed over to Moscow a huge amount of valuable documents on the secret operations of the American CIA and British MI-6 against Russia directed from the Baltic states.” According to that source, Dressen managed to uncover many foreign intelligence agents operating in Russia, as well as to thwart the attempts of Western intelligence to recruit senior Russian officials as agents. On July 3, 2012, the District Court in Harju found the Dressens guilty of treason and the transfer of secret information to a foreign agency. Aleksei Dressen was given sixteen years in prison while Viktoria received six years, though her sentence was later suspended. But just three years later, in September 2015, Dressen regained his freedom. Estonia exchanged him for their agent, Eston Kohver. The KaPo officer had been lured into a borderland forest and kidnapped by the FSB in September 2014. Despite the protests of Estonia and its Western allies, Kohver was convicted of spying and sentenced to 15 years in prison. His exchange for Dressen occurred on September 26, 2015 on the border crossing bridge at Kuniczina Gora.

SVR: Politics and Business

The Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) gathers information in Estonia of a political as well as an economic nature. There are two areas of the economy that most interest Russian spies: the transit business (one of the most important sectors of the Estonian economy) and energy. One of the focuses of Russia’s intelligence activity is known to be oil shale processing and extraction technology. The Russians’ task is made easier in that the Virumaa industrial region, where shale extraction is currently taking place, is the most Russified part of Estonia and borders Russia. Large strategic enterprises that are attractive to industrial spies operate there such as Viru Keemia Grupp or Eesti Energia Õlitööstus.

The Constitutional Party, bringing together Russian Estonians, formed to enter into parliament after the 2007 elections, was a project of the SVR. The leader of the party was Andrei Zarenkov, one of the leaders of the riots in Tallinn in 2007, and the protégé of Tatyana Poloskova, a collaborator with Russian intelligence and head of the OKA Foundation. The Constitutional Party received direct support from Russian diplomats. It did not add up to much as the group won just one percent of the vote. SVR activity increased markedly after June 1, 2007, when the visa agreement between the EU and Russia was simplified. Article 11 of the agreement provides the owners of diplomatic passports with entry into the EU without a visa and the possibility of staying in an EU country for up to ninety days within a six-month period. This way SVR officers under diplomatic cover gained greater freedom of movement, which they immediately began to use. Soon after, in June 2007, an officer of the SVR political intelligence board, Vladimir Pozdorovkin, appeared at a conference in Tallinn. In 2010 alone, twenty-two visa applications were submitted by people who the KaPo suspected of ties with Russian intelligence.

The Simm Case

The most valuable SVR agent in Estonia was Herman Simm. Over the course of more than ten years of cooperation, he gave the Russians about three thousand secret documents pertaining not only to Estonian security, but to NATO as a whole. Simm (b. 1947) worked in the militia of Soviet Estonia from 1970. In the 1980s, having risen to the rank of criminal inspector, he went to Moscow to study at the Ministry of Internal Affairs Academy of the USSR. Like many Estonians, he earned a side income by selling Western clothing smuggled from Finland. He was caught, and the KGB gave him a choice: either disciplinary dismissal from the militia or secret cooperation. He chose the latter. In 1991, Estonia regained its independence, the USSR collapsed and the KGB dissolved. After several years of work in the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the police, Simm ended up in the Ministry of Defense.

If he hoped that he had been forgotten by Moscow, he was wrong. In 1995, SVR officers showed up. As he later testified at his trial, they blackmailed him, threatening to reveal the fact of his cooperation with the KGB, so Simm decided to work for Russian intelligence. Although he later explained that he fell victim to blackmail, he managed to earn a lot from cooperation with Moscow. He took in an average of one thousand euros a month from the Russians with bonuses for particularly important information. When he was detained, Simm and his wife Heeta were the owners of seven properties and several very expensive plots. He explained his very good financial condition, to colleagues for example, as resulting from money he was supposed to have received from relatives in the West. But it was not the money that caused the first suspicions towards Simm. In 2000, the head of military intelligence, Major Riho Juhtegi, asked the head of KaPo (Inspector Jüri Pihl) to check Simm, because he was very interested in military intelligence, which was not at all within the scope of his authority as a defense ministry official. If the traitor could have been unmasked then, Estonia and NATO would have avoided heavy losses. Meanwhile, in 2001, Simm was promoted to the head of the newly created security department at the Ministry of Defense, gaining access to all state secrets.

In 2004, Estonia joined NATO and its system of protection of classified information had to be integrated with allied systems. Simm got the task of creating the Department of National Defense, as part of the Ministry of Defense, and, as its head, became the most important Estonian official responsible for protecting classified information. He then also had access to all the secrets that NATO members shared. He regularly went to NATO headquarters in Brussels. He acquired friends, was widely liked and appreciated by his superiors, but also emphasized his anti-Russian views at every opportunity. Absolutely beyond suspicion, in 2006 he received a medal from the president for “service to the Estonian people”. In the same year he got a medal from his Russian superiors and – according to unconfirmed reports – a secret promotion to the rank of major general of the SVR. This is when Western intelligence caught wind of the trail of the spy.

Information revealed later during the Simm trial and the report published by the prosecutor’s office shows that the SVR was managing its valuable agent very carefully. Russian diplomats in Estonia were not involved as they were closely observed by Estonian counterintelligence. Simm met with his case officers Valeri Zentsov and Sergei Yakovlev several times a year in various EU countries outside of Estonia. A rule had been adopted that they met each time in a different place. Yakovlev was an illegal alien, so he used the false identity of a Portuguese businessman called Jesus Amoretta Graf. It was through him that Western intelligence found the trail to Simm. Yakovlev was put under surveillance after an unsuccessful attempt to recruit an important official in one of the NATO countries in southern Europe. In 2006, Simm lost the position of the head of the security department in the Ministry of Defense, but remained as the minister’s adviser where he could copy and pass on confidential analyses to the Russians.

In cooperation with its allies, the KaPo patiently collected evidence against Simm. Finally, they slipped him a prepared document containing specific information. When Western intelligence was sure that this information was in the possession of the Russians, Simm was taken down. He was detained on September 21, 2008, together with his wife who knew about his spying activity. For many months after the Estonian was arrested, a special team assessed the scale of the damage caused to the alliance by Simm. The report from NATO’s internal investigation described Herman Simm as the most harmful Russian spy against the alliance in history. Between 2004–2006 all documents from NATO and allied countries coming to Estonia passed through the hands of a traitor. Internal investigations into potential damage caused by the Estonian were initiated by Norway, France and Germany.

The trial took place behind closed doors. On February 25, 2009, Simm was sentenced to twelve and a half years in prison and a fine of 1.7 million dollars. He avoided the maximum sentence (fifteen years) because during the investigation he pleaded guilty and cooperated with prosecutors. The KaPo leadership later revealed that the knowledge gained in the Simm case helped to uncover another Russian spy.

The Veitman Case

Vladimir Veitman was a retired KaPo employee when he was arrested in August 2013, but more importantly, he had previously worked in the KGB ESRR. He was an eavesdropping specialist. When the KaPo was formed, the management of the new service decided that only a dozen or so “technical” employees, former KGB functionaries, would be hired as no alterative uncompromised personnel could be found. The people who were carried over from the KGB were to be kept away from sensitive information and from planning and managing operations. Their function was to perform technical tasks and only when it was absolutely necessary. Veitman joined the KaPo in December 1991. His good friend from the KGB days, was Nikolai Yermakov (b. 1948). From 1975–1991 he served in the Estonian KGB, and after it was dissolved, he took up business – often travelling between Estonia and Russia. He was a citizen of Russia, but with permission to stay in Estonia, but most importantly, he cooperated with the SVR. For many years, Yermakov had no idea that Veitman was working at the KaPo. It lasted until the Estonian let it slip while complaining about his family problems. Yermakov reported about this to his superiors in SVR, and they decided to take advantage of this access. Veitman did not notify his superiors in the KaPo when the Russians began to carefully probe whether he would agree to cooperate. In the end, Yermakov convinced his friend – mainly by financial incentives – to work for Russian intelligence in 2002. Yermakov was to be Veitman’s contact, who in turn was supervised by SVR officer Valeri Zentsov, who earlier (until 2001) supervised Simm. Zentsov (b. 1946) was a veteran of the ESRR KGB (1969–1991), and after the dissolution of the KGB, he continued his service in Russian intelligence. He met Veitman only once: in August 2007 in Dubrovnik, Croatia. Arrested six years later, Veitman was found guilty of treason and sentenced to fifteen years in prison and a penalty of 120,000 euros – the amount that Veitman was to have earned over a decade of spying activity.

Agents of Influence

In a very recent KaPo annual report, the very beginning references the so-called “doctrine of Gerasimov” (Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation), who speaks of conducting war with non-military means to reduce the “readiness, will and values” of the opponent. The threat from Russia is more than just classic espionage. Therefore, in addition to the counterintelligence fight against agents, the KaPo pays particular attention to monitoring business and media environments. Estonians carefully monitor who wants to invest in their country, where, and the origin of the capital funds of the registered entity. After all, it was Putin himself in December 2010 who stressed that it was necessary to defend Russian business abroad and that it was necessary to use the technical and intellectual potential of Russian intelligence to realize the country’s economic interests. Intelligence activity carried out through media and journalists is even more dangerous. “The Russians will do nothing militarily without creating an internal threat – or the impression of one, absent a real threat. Information is not a goal but a tool. The goal is not information, but influence”– in the words of Martin Arpo, a high ranking KaPo officer.

Reporters sent from Russia often have a second job: in intelligence. They produce content and reports according to scripts written earlier at headquarters. According to a counterintelligence report: “They all paint the image of post-soviet Estonia as an economically, socially and culturally degenerated country on the periphery of Europe, where neo-Nazism flourishes, and the Russian-speaking population is discriminated against” (Aastaraamat 2010, Kaitsepolitsei). It is not much better with the Russian-language media in Estonia, which is full of agents. For example, the magazine Baltijskij mir is indirectly financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, and its editor-in-chief, a former correspondent of the Regnum News Agency, Dmitry Kondraszov, is, according to the KaPo, a person associated with Russian intelligence. In turn, the owner of the Tarbeinfo publishing house is Vladimir Ilyazhevich, a former officer of the First Main Directorate of the Committee for State Security of the USSR (KGB foreign intelligence), and an active member of the Russian-speaking community in Estonia.

The media is an important part of Moscow’s intelligence battle against Estonia. Effective counteraction is difficult because about forty percent of ethnic Russians in Estonia do not speak any Estonian, and two-thirds of them do not come into contact with the Estonian media at all. The Russian media is a powerful instrument for manipulating the awareness of a very large part of Estonia’s Russians: research conducted in 2014 shows that in the case of conflicting reports, only six percent of them believe the Estonian media. Most trust the Russian media.

[1] M. Weiss, “The Estonian Spymasters: Tallinn’s Revolutionary Approach to Stopping Russian Spies,” Foreign Affairs (June 3, 2014) accessed February 12, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/central-europe/2014-06-03/estonian-spymasters.

All texts published by the Warsaw Institute Foundation may be disseminated on the condition that their origin is credited. Images may not be used without permission.